Jakub Jasiński

It all started with a reading session. As a student of Classical Philology, I was no stranger to the ancient world’s treasure trove of literature. Yet, as I flipped through Pausanias’ Description of Greece, a travelogue of the Greek world written nearly two thousand years ago, I found something unexpected: a mention of the Heraean Games. These were athletic competitions held in Olympia, not for men, but for women, in honor of the goddess Hera.

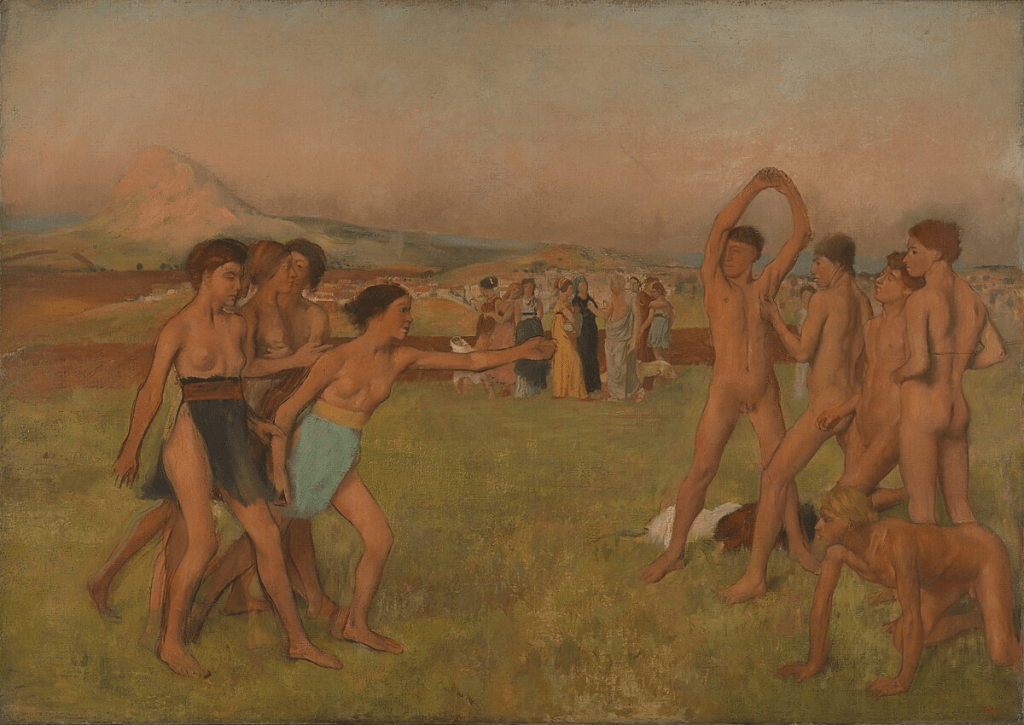

The idea fascinated me. While the Olympic Games and their male champions dominate popular images of Ancient Greek sports, here was an almost forgotten counterpart – a celebration of female physicality and competition. This discovery grew into an exhibition: together with a group of fellow students, I set out to explore how women in Ancient Greece engaged in physical activities, from sports and dance to ritual performances.

When we began planning Sports Competitions and Physical Activity of Women in Ancient Greece, one of the first challenges we faced was how to structure the story. The Ancient Greek world was vastly diverse, with each city state offering unique perspectives on women’s roles in physical activity. We decided to focus on three key themes: the regional differences in women’s athletic lives; the inspiring figures and myths that shaped their image; and broader cultural practices such as sports festivals and rituals. How did Spartan and Athenian women’s experiences differ? What could myths such as those of Atalanta and historical figures such as Cynisca tell us about women’s agency? And how were sports and physical activities woven into religious and social practices?

As we started piecing together the exhibition, we realised it was essential to explore the Bronze Age, and the vibrant and enigmatic civilization of the Minoans, which emerged around 3100 BC, rose to its height between 2000 and 1450 or so, and lasted until around 1100 BC. Their culture offered a compelling starting point, not only because of its early influence on later Greek traditions, but also due to its striking depictions of women in athletic and ritualistic roles.

Minoan women seem to have actively participated in activities such as hunting, gathering, and the Minoans’ iconic, enigmatic ritual of ‘bull-leaping’. Famous frescoes such as the ‘Toreador Fresco’ from the palace complex at Knossos illustrate women leaping over bulls, grasping their horns, or taking part in hunts and other such rituals. These depictions suggest a significant role for women in both Minoan society and its ceremonial life. Scholars have interpreted ‘bull-leaping’ as a rite of passage, or a devotion to deities associated with nature and fertility. Such practices must have influenced the development of ritualised athleticism seen in later Greek cultures, where physicality often held both social and sacred significance.

In Spartan civilization, which began to flourish in the 8th century BC, and lasted into the Hellenistic period, vibrant traditions of physicality and athleticism, as seen in Minoan culture, found a more structured, socially-driven expression. Where Minoan women’s physicality was steeped in ritual, Spartan women’s athleticism became a civic duty, reflecting the state’s unique priorities. Here, the evidence of female sports and physical training reflected not only ritualistic practices but also societal goals. Its physical education system was unlike any other in the Greek world, shaped by a broader societal focus on eugenics, with the goal of producing strong, healthy offspring.

Spartan laws, attributed to the legendary lawgiver Lycurgus, mandated rigorous physical training for girls, with the belief that strong mothers would give birth to strong warriors. This philosophy is reflected in the words of Plutarch:

τὰ μέν γε σώματα τῶν παρθένων δρόμοις καὶ πάλαις καὶ βολαῖς δίσκων καὶ ἀκοντίων διεπόνησεν, ὡς ἥ τε τῶν γεννωμένων ῥίζωσις ἰσχυρὰν ἐν ἰσχυροῖς σώμασιν ἀρχὴν λαβοῦσα βλαστάνοι βέλτιον, αὐταί τε μετὰ ῥώμης τοὺς τόκους ὑπομένουσαι καλῶς ἅμα καὶ ῥᾳδίως ἀγωνίζοιντο πρὸς τὰς ὠδῖνας.

He made the maidens exercise their bodies in running, wrestling, casting the discus, and hurling the javelin, in order that the fruit of their wombs might have vigorous root in vigorous bodies and come to better maturity, and that they themselves might come with vigour to the fulness of their times, and struggle successfully and easily with the pangs of childbirth. (Lycurgus, 14.2, trans. B. Perrin)

This approach wasn’t merely theoretical. Unlike in most other Greek city states, these activities were not merely tolerated but celebrated, and girls participated in them reflecting the value placed on physical prowess in Spartan society.

The story of Spartan women’s athleticism continues outside the city state with the figure of Cynisca, a Spartan princess who broke barriers in the traditionally male-dominated arena of the Olympic Games. Around the early 4th century BC, Cynisca became the first woman recorded to win at the Olympics, not as a competitor but as the owner of a victorious chariot team. Cynisca’s Olympic victory enables us to move beyond isolated Spartan laws and examine how female participation in sports was policed and constrained across Greek society.

By sponsoring a chariot team, Cynisca asserted that women, though barred from direct competition, could still claim a role in the most celebrated athletic competition of the ancient world. Her success was immortalised with inscriptions and statues: for example, an inscription now in the museum at Olympia proclaims:

Σπάρτας μὲν βασιλῆες ἐμοὶ πατέρες καὶ ἀδελφοί, ἅρματι δ’ ὠκυπόδων ἵππων νικῶσα Κυνίσκα εἰκόνα τάνδ’ ἔστασεν μόναν δ’ ἐμέ φαμι γυναικῶν Ἑλλάδος ἐκ πάσας τόν δε λαβεῖν στέφανον. Ἀπελλέας Καλλικλέος ἐπόησε.

Kings of Sparta are my father and brothers. I, Cynisca, victorious with a chariot of swift-footed horses, have erected this statue. I declare myself the only woman in all Hellas to have won this crown. Apelleas son of Callicles made it.

Yet the story of Callipateira provides a striking contrast. A widow of noble lineage, Callipateira disguised herself as a man to watch her son compete at Olympia at the games in 388 BC, defying the strict ban on women even attending the such events. Though her identity was eventually discovered, her family’s legacy as Olympic champions spared her from punishment. Her act of daring emphasises the tension between social restrictions and this woman’s determination to participate in an athletic tradition.

The Heraean Games offered a rare example of an athletic institution exclusively for women. Held at Olympia, the same site as the Olympic Games, but dedicated to the goddess Hera, the Heraean Games provided young, unmarried women with a unique opportunity to showcase their physical abilities in a celebrated public setting.

According to legend, the Heraean Games were established by Hippodamia who, in gratitude to Hera for her marriage to Pelops, gathered sixteen women to organise the first competition. These women, referred to in some sources as the ‘Sixteen Women of Elis’, not only managed the games, but also wove a peplos (ceremonial garment) for Hera, demonstrating the religious as well as the social functions of the event.

Historians debate whether the Heraean Games predated, or were inspired by, the Olympic Games. They featured a single event: a footrace divided by age groups for girls between six and eighteen years of age. The race took place on the same track as the men’s events, though the course was shortened to approximately 160 meters. Participants wore distinctive outfits – a short chiton leaving one shoulder bare, similar to male athletes’ attire during training.

Winners were awarded olive crowns, portions of sacrificial meat, and the honour of having their images displayed in Hera’s sanctuary. This demonstrates how physical competition could serve as a rite of passage, preparing girls for adult responsibilities while honoring the divine. These games also remind us that even within a patriarchal society, women could carve out spaces to express their strength and skill, often through rituals that blended athleticism with devotion to the divine.

In our eyes, the ultimate intersection between the sacred and the physical took place at Brauron. The Arkteia, a ritual held there in honour of Artemis, added another layer to the story of women’s physicality and its connection to the divine. According to legend, the sanctuary’s sacred bear once attacked a young girl, blinded her, and was later killed by the girl’s brother. In response, Artemis decreed that girls must “become bears” (arkteusai) to honour her and prevent further divine wrath.

This mysterious rite invited girls between five and ten years old to participate in symbolic physical trials. They ran with saffron-dyed ropes and performed ritual dances, dressed in short robes while wearing their hair loose. These acts marked their transition toward adulthood and readiness for future roles as wives and mothers. The exact nature of the Arkteia is still debated – did “becoming bears” mean mimicking the animal, or performing dances, or engaging in some other symbolic action?

Our exhibition, Sports Competition and Physical Activity of Women in Ancient Greece, explored far more than the major themes of Minoan bull-leaping, Spartan athletics, and the Heraean Games. It examined the mythological narratives of figures such as the Amazons and Atalanta, the transformative power of dance in both ritual and daily life, and a range of smaller but significant aspects of women’s sports and physicality, to provide a multifaceted view of Ancient Greek women’s roles as athletes, performers, and participants in religious and social traditions.

Bringing this exhibition to life was as much a journey for us as it was an exploration of history. What began as a single reference in Pausanias’ Description of Greece became a collaborative effort to uncover and present stories that have often been overshadowed. Each artifact, text, and fresco we examined added depth to our understanding, while the creative process of crafting the exhibition taught us the value of presenting complex ideas in an accessible manner.

Our project was a collaborative effort by (left to right) Jakub Jasiński, Bartłomiej Panek, Urszula Góral, and Laura Szczypek, under the academic supervision of Professor Monika Miazek-Męczyńska. The exhibition, Sports Competition and Physical Activity of Women in Ancient Greece, officially opened on October 2, 2024, at the Faculty of Polish and Classical Philology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland.