Jerzy Danielewicz

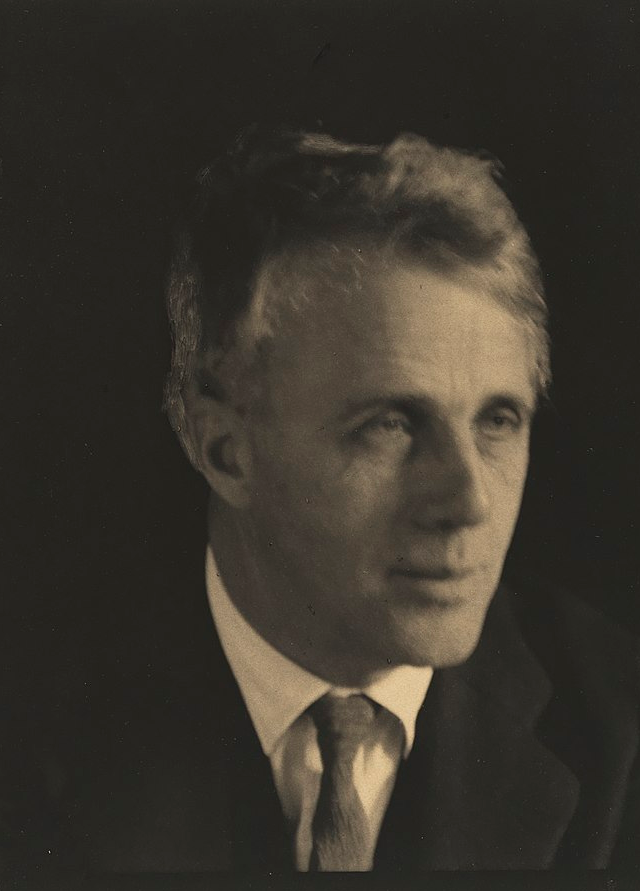

Last year marked the 150th anniversary of Robert Frost’s birth, while 2025 marks the 110th anniversary of the composition of his poem “The Road Not Taken”. Frost has won high praise from critics ever since the publication of his first collections of poems, becoming one of the foremost American poets of the 20th century and enjoying widespread public admiration. “The Road Not Taken” was first published in the August 1915 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, and later included in his 1916 collection Mountain Interval.

This poem, alongside certain other brilliant lyrics, such as “Fire and Ice” and “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”, are so widely recognised and frequently quoted that they have the effect of somewhat obscuring the poet’s wide range of achievement.[1]

“The Road Not Taken” reads:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

This apparently simple piece allows for multiple interpretations. It is hard to believe that the author intended it to be simply a joke for his friend Edward Thomas (1878–1917), a poet, critic and novelist who, during their walks together, often could not decide which path they should take, and after a time complained that they should have chosen the other one. However, their correspondence confirms the fact. Thomas, unlike Frost, saw the poem as a serious reflection on the need for decisive action. The students to whom Frost read it also took it quite seriously – even though his manner of reading suggested the opposite.

Indeed, implicit playfulness is in Frost’s nature, and by no means precludes other readings of this seemingly occasional poem. As Katherine Robinson writes, “As his joke unfolds, Frost creates a multiplicity of meanings, never quite allowing one to supplant the other—even as “The Road Not Taken” describes how choice is inevitable”.[2] A choice does not mean a better or more original choice, and the reader’s expectations fail. David Orr, in his famous 2015 essay on the poem, demystifies ready labels and fallacious interpretations, writing:

A cultural offering may be simple or complex, cooked or raw, but its audience nearly always knows what kind of dish is being served. – – – Frost ’s poem turns this expectation on its head. Most readers consider “The Road Not Taken” to be a paean to triumphant self-assertion (“I took the one less traveled by”), but the literal meaning of the poem’s own lines seems completely at odds with this interpretation. The poem’s speaker tells us he “shall be telling,” at some point in the future, of how he took the road less traveled by, yet he has already admitted that the two paths “equally lay / In leaves” and “the passing there / Had worn them really about the same.” So the road he will later call less traveled is actually the road equally traveled. The two roads are interchangeable.[3]

To put it in other terms, the temporal and spatial deictic strategy adopted in this piece proves highly deceptive; the attentive reader should be aware of this.

It is worth noting that the motif of a fork in the road (or a crossroads) and the associated pair (or range) of choices it implies (when considered from different perspectives) has been exploited quite widely in poetry. Of the poems from the last century and a half, a number of important ones along these lines have caught my attention. Before Frost, the topos was taken up by Richard Hovey (1864–1900), “At the Crossroads” (published in 1898) and Guido Gozzano (1883–1916), “Le due strade” (published in 1911). As for Frost himself: a fascinating antecedent is pointed out by Faggen, namely “Our journey has moved forward” by Emily Dickinson (written c.1862, but first published in Poems, 1891):[4]

Our journey had advanced—

Our feet were almost come

To that odd Fork in Being’s Road—

Eternity—by Term—

Our pace took sudden awe—

Our feet—reluctant—led—

Before—were Cities—but Between—

The Forest of the Dead—

Retreat—was out of Hope—

Behind—a Sealed Route—

Eternity’s White Flag—Before—

And God—at every Gate—

It might be added that crossroads as a metaphor by which to frame reflections on life has not ceased to captivate American poets after Frost. It is taken up, among others, by Joyce Sutphen, “Crossroads” (1995) and – already in the 21st century – laureate of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature, Louise Glück, “Crossroads” (2009).[5]

Here is my translation of Frost’s poem into Ancient Greek iambic trimeters:

Ἡ οὐχ αἱρεθεῖσα ὁδός

Χλωρὰν καθ’ ὕλην εἰς δίχ’ ὁδὸς ἐσχίζετο·

εἶτ’ ἀμφοτέρας μὴ δυνάμενος γ’ αὐτὸς πατεῖν

ἤσχαλλον ἠδ’ ἐκεῖθι δηρὸν ἱστάμην

ὡς ἐδυνάμην πόρσιστα τὴν προτέραν σκοπῶν

ἕως ἀποκλιθεῖσα κατὰ λόχμας ἔδυ.

ἔπειτα τὴν ἄλλην ἴσ’ ἐρατὴν ἀτραπόν

ἐβάδιζον, ἥ τ’ ἔοικε μᾶλλον αἱρετή,

ἦν γὰρ ποώδης ἠδ’ ἐδεῖτο τοῦ πατεῖν,

ἐνῆν ὅμως κοινόν τι γ’ ἀμφοτέραις ὁδοῖς·

τετριμμέναι πόσσ’ ἦσαν ἐξ ἴσου σχεδόν.

ἔκειντ’ ἴσως κατʼ ὄρθρον ἐν φύλλοις τότε

ἠδ’ οὐδὲν ἐμελαίνοντο βημάτων τύποις.

ἀφῆκα τὴν προτέραν ἐς ὕστερόν ποτε,

εἰδὼς δὲ τὰς ὁδοὺς τάχ’ εἰς ἄλλας φέρειν

ἂψ αὖτις ἥξειν ἔνθα γ’ ἠπίστουν πάνυ.

ἦ μὴν περιπλομένων ἐτῶν λυπούμενος

ἐν ἡμέρᾳ τινί που γέρων λέξω τάδε·

πάλαι καθ’ ὕλην εἰς δίχ’ ὁδὸς ἐσχίζετο,

ἐγὼ δὲ τὴν ἐρημοτέραν προειλόμην·

ἔνθεν τὰ λοιπὰ πάντα διαφόρως ἔχει.

I take the opportunity here to add a few words of commentary on my translation. Frost’s ambiguous text presents the translator with the difficult dilemma of how to render its nuances in the target language. For example, already the word “taken” in the title seems marked by ambiguity.[6] I chose αἱρεθεῖσα, “chosen”, emphasising the aspect of the original choice. The words “travel” and “traveller” also pose a problem. With the situational background of the piece in mind, I chose πατεῖν, “tread”, “walk”.

Anyway, the road, which “was grassy”, invited walking on foot rather than wearing down with, say, the wheels of a vehicle.[7] Besides, in the third stanza, the poet speaks of the roads: “And both that morning equally lay / no step had trodden black.” I have dispensed with translating “Oh” because the available Greek exclamations would not convey the tone of this sigh in English.

I did not hesitate, though, about the verse measure: iambic trimeter came to mind as the obvious choice for rendering the English ‘iambic tetrameter’ (of course with all awareness of the different meaning of the repeated rhythmic unit). I have used its looser form,[8] consistent with the realisation of Frost’s tetrameter, which Timothy Steele describes as follows:

In writing in meter… Frost modulates the measure from within, laying various and vital segments of speech across the grid so as to adhere to the paradigm without mechanically or monotonously replicating it. The fundamental pattern is constant, but the individual verse lines embody it in ever-changing ways.[9]

The Greek translation, as it were, takes us back to the Ancient Greeks, and prompts us to theorize about the associations that this type of poem might evoke in them. The crossroads functioned there, as in the folklore of many peoples, as a special, demonic, magical and also frightening place. The parallel for Frost’s poem, however, is not so much the crossroads or ‘fork’ per se, as conceived in static terms, but the crossroads as a starting point in which a decision is made how to proceed.

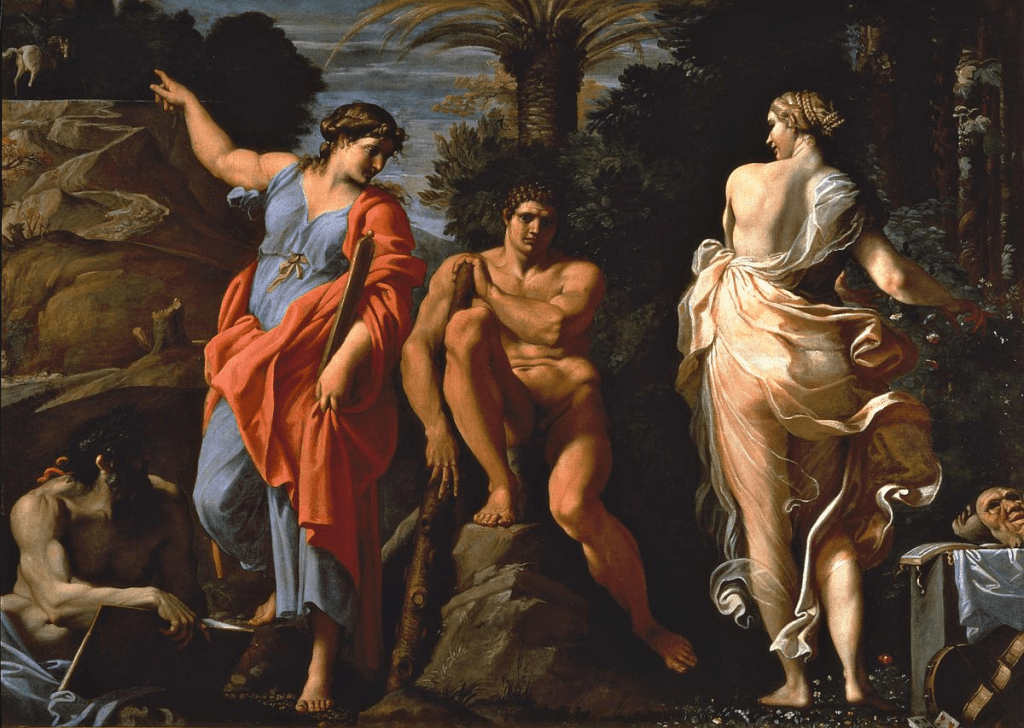

In this respect, a suitable analogy is the well-known story of Heracles, which has been referred to as “one of the most influential pieces of world literature”, the first to combine the idea of choice with the image of the road and the crossroads.[10]

This story (charmingly paraphrased in Xenophon’s Memorabilia 2.1.21–34), tracing its origin to the 5th-century BC sophist Prodicus of Ceos, tells how young Heracles, as he was walking alone one day, suddenly came to a crossroads that diverged into two paths. While he was confused about which one to take, he was joined by two young women whose names derived from the qualities they embodied: Arete (Virtue) and Kakia (Vice), each dressed according to her role. Having listened to their ‘recommendations’, Heracles chose the less tempting path of Virtue, and secured himself sweat and tears in the short term, but ultimately immortality too.

Incidentally, the idea of choosing between opposites, in this case living in poverty versus enjoying the delights of life, was explored, metaphorically and humorously, in the anonymous collection Theognidea at 911–14:

ἐν τριόδῳ δ’ ἕστηκα. δύ’ εἰσὶ τὸ πρόσθεν ὁδοί μοι·

φροντίζω τούτων ἥντιν’ ἴω προτέρην·

ἢ μηδὲν δαπανῶν τρύχω βίον ἐν κακότητι,

ἢ ζώω τερπνῶς ἔργα τελῶν ὀλίγα.

I’m standing at a junction, with two ways ahead,

and I’m deliberating, which to choose:

to cut all spending and exist in misery,

or to have fun, achieving nothing much. (tr. M.L. West)

I have limited myself to only a couple of examples that would illustrate the motif of our interest. As a final instance, I save a delicious snippet from Oppian’s Halieutica (“Fishing” or “A poem about fish and fishermen”, late 2nd cent. AD). In the third book of this epic poem (lines 499–506), the poet includes a description of a ‘cephalus’, lured by the mint attached to the hook, comparing it to a wanderer at a crossroads who hesitates about which path to take before deciding on one:

κεστρεὺς δ’ οὐ μετὰ δηρόν, ἐπεί ῥά μιν ἷξεν ἀϋτμή,

ἀντιάσας πρῶτον μὲν ἀποσταδὸν ἀγκίστροιο

λοξὸν ὑπ’ ὀφθαλμοῖς ὁράᾳ δόλον, εἴκελος ἀνδρὶ

ξείνῳ, ὃς ἐν τριόδοισι πολυτρίπτοισι κυρήσας

ἔστη ἐφορμαίνων, κραδίη τέ οἱ ἄλλοτε λαιήν,

ἄλλοτε δεξιτερὴν ἐπιβάλλεται ἀτραπὸν ἐλθεῖν·

παπταίνει δ’ ἑκάτερθε, νόος δέ οἱ ἠΰτε κῦμα

εἱλεῖται, μάλα δ’ ὀψὲ μιῆς ὠρέξατο βουλῆς.

And in no long time the Grey Mullet, when the odour reaches him, first approaches the hook distantly and regards with eyes askance the snare; like to a stranger who, chancing upon much trodden cross-ways, stands pondering, and at one moment his heart is set on going by the left road, at another by the right, and he looks on this side and on that and his mind fluctuates like the wave and only at long last he reaches a single purpose. (tr. A.W. Mair)

Frost would probably have been surprised to see an antecedent which makes his own original description seem like a shade, or unconscious echo of the ancient past.[11]

Jerzy Danielewicz is Professor Emeritus of Classics at Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań. A passionate translator of poetry, he has recently published an anthology of world lyric poetry from antiquity to the present under the title Cierń nostalgii (The Thorn of Nostalgia). For his translations of Mickiewicz’s lyrics into Greek and Latin in Antigone, see here.

Notes

| ⇧1 | This was pointed out by Robert Faggen, The Cambridge Introduction to Robert Frost (Cambridge UP, 2008) vii. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Katherine Robinson, “Robert Frost: ‘The Road Not Taken’,” Poetry Foundation, May 27, 2016, available here. |

| ⇧3 | David Orr, “The most misread poem in America,” New York Times, 20 August 2015. |

| ⇧4 | Faggen (as n.1) 16. |

| ⇧5 | To the names mentioned, one could add Edwin Tavarro’s “Crossroads” (2011) and, in France, Michel Granier, “La croisée des chemins” (2018). Dana Gioia has woven an interesting ‘Hekatean’ theme into his piece “At the Crossroads” (2023). |

| ⇧6 | Cf. Faggen (as n.1) 142: “He [Frost] uses the verb “take” to assess the roads, and it is the same verb used colloquially for the road actually chosen”. |

| ⇧7 | Stanislaw Barańczak (1946–2014), an eminent translator of poetry written in English into Polish (from Chaucer to Larkin) takes the latter possibility for granted. For a contrast, compare the spontaneous response to nature by Sergei Esenin (1895–1925) in his poem “Не жалею, не зову, не плачу” (“I do not regret, complain, or weep”): И страна березового ситца / Не заманит шляться босиком (“The birch woods cotton print / No more tempts me to roam barefoot”, tr. Daniel Weissbort). |

| ⇧8 | In an attempt to give a rhythmic effect equivalent to Frost’s loose iambics, I have used licenses attested in Greek tragedy and freely admitted in comic verse, namely double short replacing any anceps position or short, except for the short of the last foot. The comic trimeter is better suited for a colloquial style; Frost himself, between 1913 and 1915, in a series of letters, interviews, and public talks, justified his use of colloquial speech in his work and asserted his originality in doing so. |

| ⇧9 | T. Steele, “Across spaces of the footed line: the meter and versification of Robert Frost,” in R. Faggen (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Robert Frost (as n.1) 123. A recording of his recitation is available, among others, here. |

| ⇧10 | For a discussion of this topic, including the analogies that the folktale’s quest can supply for Prodicus’ picture of Heracles in aporia (perplexity), see M. Davies, “The hero at the crossroads: Prodicus and the Choice of Heracles,” Prometheus 39 (2013) 3–17. |

| ⇧11 | For all his knowledge of Classical literature, Frost was probably not that widely familiar with Greek poetry. His favourite authors included Euripides, Plato, Virgil, Horace and Ovid: cf. H. Bacon, “Frost and the ancient Muses,” in Faggen (as n.1) 75–100. |