Edmund Stewart

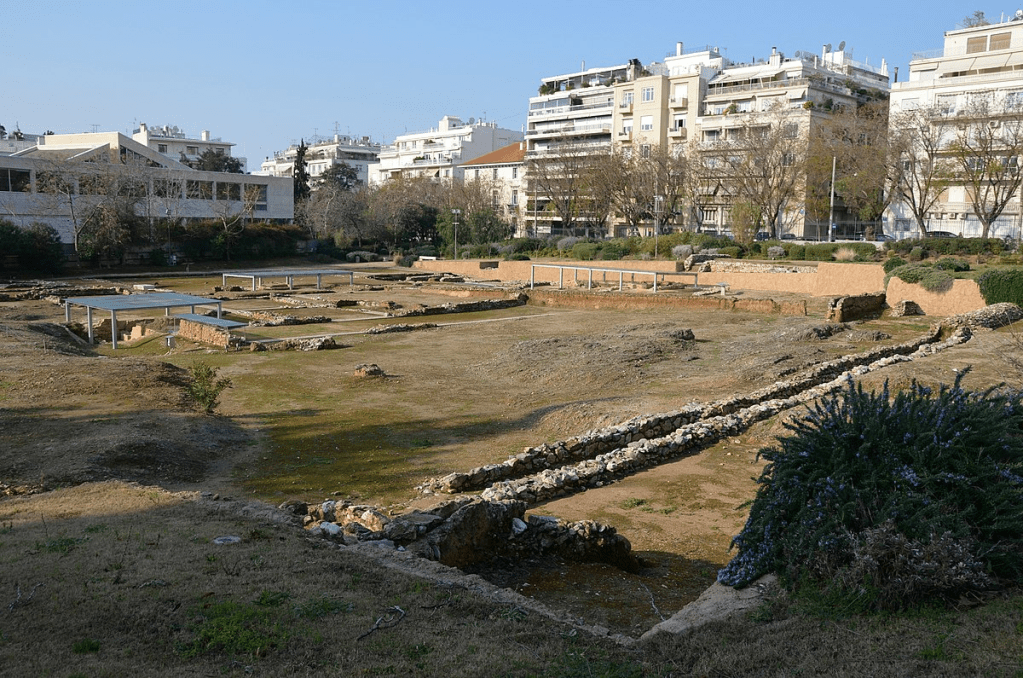

In 1996, construction workers in central Athens unearthed what looked like the remains of an ancient building. This is by no means an uncommon occurrence, but what they discovered would prove to be no ordinary find. The site was a short walk from Syntagma Square and the Greek Parliament building, under the slopes of Mt Lycabettus. In ancient times, this area was just outside the south-eastern corner of the classical city. It was precisely in this rough location that the gymnasium of the Lyceum was known to have been situated. And, when excavations finally began in 2011, this was exactly what the archaeologists uncovered.

The diggers had found one of the most important places in the global history of thought and philosophy. The Lyceum was a pleasant, well-watered exercise ground dedicated to Apollo Lyceus, that is the ‘wolf’ god. It was one of three similar extra-mural sanctuaries, the others being the Cynosarges (a sanctuary of Heracles also south of Athens) and the Academy (belonging to the hero Hacademus, to the north west) – another location that, like the Lyceum, has given its name to countless later educational establishments across the world.

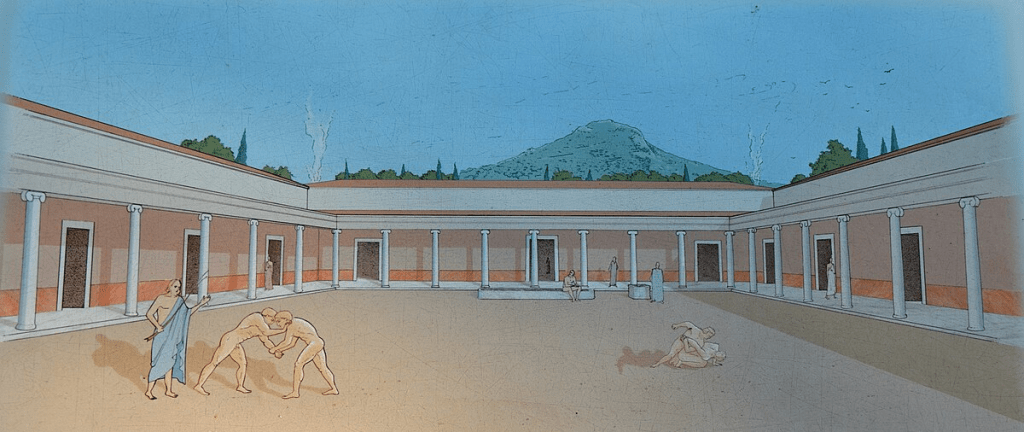

These sites were developed from as early as the 6th century BC as places for military drills, athletic exercise and general recreation. However, from the 5th century they were also regularly frequented by “sophists”. These were self-professed teachers of young men in what they needed to know to become both good citizens and good men. To begin with, the sophists discoursed in public places and worked as individual tutors to elite clients. They each had their own students and teenage boys would wander between them. Their practice was not very different from those of the professional writing masters and athletic trainers who taught younger boys their letters, as well as the basic skills of how to strum the lyre and how to box, run and wrestle.

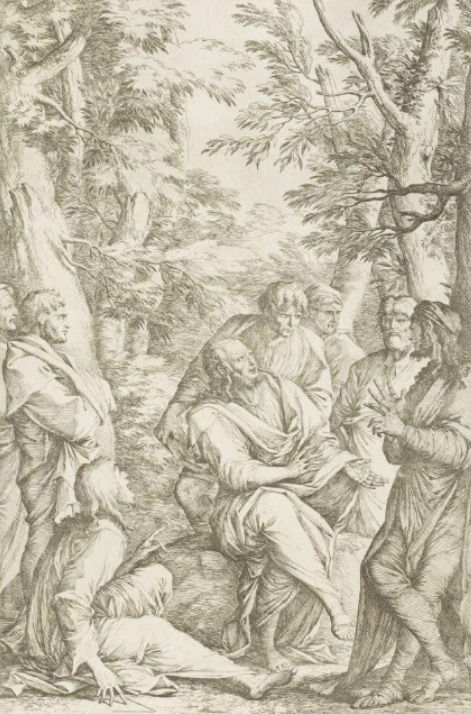

Athens in the latter half of the 5th century played host to a brilliant galaxy of international thinkers, who are mostly now obscure to all but subject-specialists – the likes of Protagoras of Abdera, Hippias of Elis and Prodicus of Ceos. But by far the most important of the companions of the sophists was the Athenian Socrates (c.470–399 BC). The Lyceum was one of his favourite haunts, where he used to watch the boys exercise and discourse with the older teachers, such as the brothers Euthydemus and Dionysodorus of Chios, experts in military tactics and ‘virtue’, or Prodicus, who used the Lyceum as a venue for his lectures.

One of Socrates’ pupils and successors, Aeschines the Socratic, described in a lost philosophical dialogue seating at the Lyceum for these events. The later 4th-century gymnasium included side-rooms which seem to have been designed for philosophical teaching. But the Lyceum was not Socrates’ ‘school’: he wandered about Athens and could as often be found taking the road that circled the city, from the Diochares to the Dipylon gates, back towards the Academy.

Socrates was condemned for “corrupting the youth” in 399 and duly drank his poisoned cup of hemlock. But his later reputation was assured by his most brilliant pupil, Plato the son of Ariston. Plato (428/7–348/7 BC) was not in the prison when Socrates died, but he was perilously close to his master and was one of the students who had promised to post bail on his behalf. He fled Athens for Megara and then began an international tour that would take him as far as Sicily.

There the major city of Syracuse had fallen under the dominion of the most powerful tyrant the Greeks had known up to that point. His name was Dionysius and by the end of the 380s he would control not only his native city, but the Greek cities of eastern Sicily and, with the capture of Rhegium in 387, the all-important straits of Messina. He was fabulously rich and, like other tyrants before and after him, he spent the money not just on arms and fortifications, but also on patronage for poets, artists and thinkers. At some point he built a temple of the Muses (a Museum) and filled it with artworks and treasured memorabilia, such as a writing tablet that belonged to Euripides. This may well have formed the central focus of an intellectual and cultural community in the acropolis at Syracuse.

It is possible that Plato’s stay under the patronage of the tyrant gave him the inspiration for the great project of his life (besides, that is, his major dialogues such as the Republic and Laws): he would found a community of philosophers, such as the one he joined under the roof of the tyrant, but one that could also be free of excessive interference from a single powerful patron. His voyages abroad might even perhaps be construed as a search for funding for this new institution. He certainly gained in Sicily a major funder, not the tyrant himself, but the brother of one of Dionysius’ wives (he was a bigamist incidentally), that is Dion son of Hipparinus.

Dion’s father had been an early supporter of Dionysius’ bid for power and had benefited massively. Once a bankrupt, he would later bequeath to Dion a fortune worth as much as a hundred talents. For comparison, this would have made him by far the richest man in Athens (by contrast the father of Demosthenes left his son a measly fourteen talents, which still made him liable for the highest possible tax band). Dion, then, had extensive resources and it was he who provided the comparatively meagre sum of 2,000 drachmas (i.e. a third of a talent) which secured land for a philosophical school in the Academy at Athens.

What did the new ‘school’ (σχολή, scholē) consist of? It has been suggested that the ‘gymnasium’ excavated at the Academy was in fact a purpose-built library and building for teaching (unlike that at the Lyceum, which was designed with both athletics and philosophy in mind). There was also a Museum, by which Plato was later buried. And there were spaces for teaching, exhedrai. The philosophers commissioned statues of founders and leaders of their schools to decorate their school. They also owned slaves, or employed freed slaves, who kept these buildings in order and tended their gardens.

Philosophical discussions were open to all and Plato at least did not charge fees from those attending his classes (he rather lived off ‘gifts’ from his wealthy pupils, as well as his own resources). It seems rather as if the Academy became something of a tourist destination for foreign visitors to Athens at festival time. Philosophers not only taught, but also conducted research, published books, and collected them. And – a significant departure from the past – the philosophers and their pupils regularly lived in the grounds of the Academy. A mosaic from Pompeii shows them at work and in thought, with books scattered about a garden. The Acropolis of Athens can be just seen in the distance.

The Academy was the first school of philosophy. When Plato died, the leadership of the community passed to his nephew Speusippus. The greatest of Plato’s pupils, Aristotle, the son of a court physician of the Macedonians from Stagira in northern Greece, left on his own foreign tour. In particular, he was to act as tutor to the young Alexander the Great. On his return to Athens in 335 he settled not at the Academy, but back at the Lyceum. This would be the place where he conducted and published some of his most important research, including fundamental works on logic, politics, ethics, rhetoric, poetry and natural philosophy.

Aristotle was forced out of Athens following the death of Alexander in 323, but his school was later re-established there by his successor Theophrastus of Eresus. Foreigners such as Aristotle and Theophrastus could not usually own land at Athens, but a special dispensation by the despot Demetrius of Phalerum, a friend of the philosophers, allowed Theophrastus the right to own the garden and houses of the Peripatos, which he bequeathed, at the time of his death in 287, to his followers for them to live in and use in common.

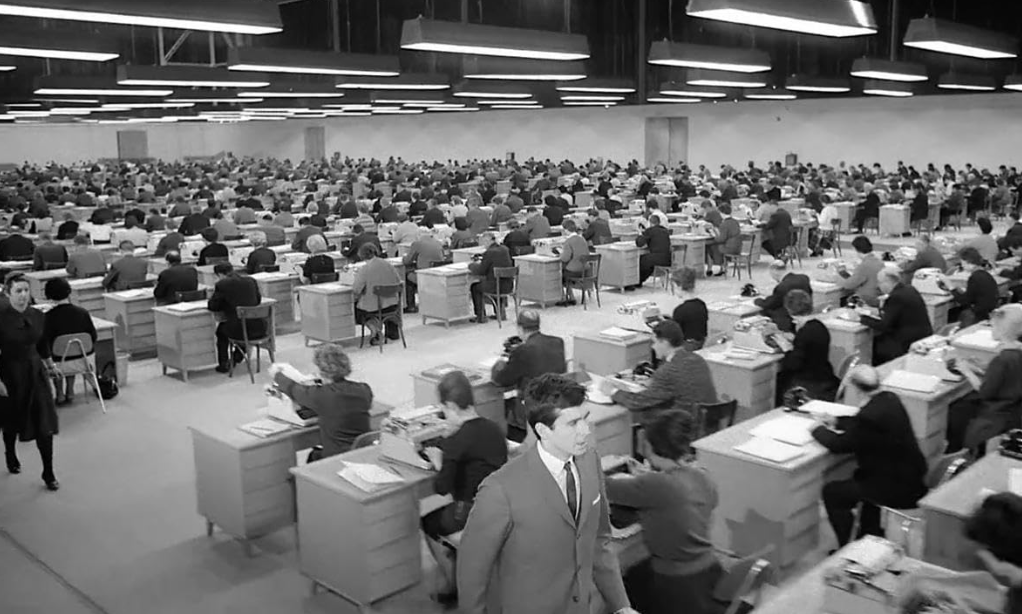

Were these early schools the first universities? There are some tempting parallels, but also clear differences. There were lectures, but no lecture courses, no modules, no curriculum. Most especially, there were no examinations and they issued no qualifications. At most, one might say, “I was a pupil of Plato.” Students came and went as they pleased. It has been suggested that the schools were legally constituted as religious associations, but this has been disputed. The bureaucratic elements of the modern university are, in sum, completely absent.

Nonetheless, ancient philosophers were professional scholars in one particular sense. Their identity, as individuals and as a group, was based on the practice of teaching and producing research, to which they devoted their whole lives. They also gained either a living or financial support from their pupils, which enabled them to carry out these functions.

One might add that there is something special about the ancient philosophical schools which is central to the purpose and function of our modern universities – and which is steadily being lost. The philosophers aimed to create good men through technical discussions of philosophical questions on a broad range of subjects. The aim of education was the betterment, and nurturing, of human souls, through a life of contemplation. This is achieved in a community of like-minded souls, who have the time and resources to devote themselves to contemplation. Students learn not a curriculum, but they learn to be like Socrates and like Plato. They learn wisdom through keeping company with the wise.

Before we dismiss this aim as laughably idealistic, we may as well ask whether the scholars of antiquity were any less productive or successful than their modern counterparts in contemporary Humanities departments? Some of the greatest foundational works of human thought were produced in the Academy and Lyceum. The communities founded by Plato and Aristotle nurtured some of the greatest minds of antiquity and the leading statesmen of that age. Is this not sufficient, and tangible, success?

If the Greek philosophical schools were the first universities, then their successors in the West have lost sight of their original specialist function, which is to seek knowledge. If we seek knowledge for its own sake, other good things will follow. Yet there now exists in most universities in the West a bureaucracy that exists for its own sake and which works to make its own priorities more and more the ‘core business’ of students and scholars. This bureaucracy has come about to serve the ever expanding ends of government and to ensure compliance with government regulations. Government, in demanding value for money for students, has made employability and skills, not knowledge alone, the prime focus of universities.

Are employability and skills really enough to foster the best possible citizens of the future, or the best academic outcomes? Students today are more often trained than educated. And yet all the while we remain blind to the truth that any educated person can be trained to do a job, but that training in a job is no education. Universities produce specialised workers for the wider division of labour. These are docile members, designed for installation into corporate bodies. Yet the Humanities were not intended for this, but for the creation of whole human beings.

Students are taught, in Aristotelian terms, to know ‘that’, not to know ‘why’. The only conceivable purpose for which they learn is to make money, not to seek the goal of happiness through contemplation that was the supreme telos (goal) for Aristotle. The ancient philosophers would have had no difficulty in identifying our trainee management consultants and nascent marketing managers, manufactured today at ever faster rates, as precisely the type of drudges they called banausoi – trained workers, not wise citizens. The only surprise would be that it is now institutions founded for the purpose of education which are actively promoting a blend of myopia and barbarism.

What is needed to combat this rot and to halt the decline of the Humanities is a new Humanism, not just that of the Renaissance, but of the Greek philosophers as well. Change must come from teachers and scholars. Academics need to work not just to sell degrees, but rather to seduce their students with a genuine love of knowledge and virtue. We need to nurture the Alexanders of our own day in a place where they can, briefly, live the life of contemplation. And we need to inspire them with a desire to return, even years later, back from the busyness of life and the tables of the traders, back to the grove of the Academy, the wrestling grounds of the Lyceum, to take time to sit in the garden of Epicurus or to walk in peace beside Ilissus’ pleasant waters, arm-in-arm with Socrates.

Edmund Stewart is Assistant Professor in Ancient Greek History at the University of Nottingham. He has previously written for Antigone on how to build a Greek temple, and his other essays can be found via our writers page.