Robin Douglas

Would you like to ascend to mystical union with the gods by inhaling sunlight, while seeing off any demons that you happen to meet on the way? An Ancient Greek text may be able to offer you some guidance.

A common perception of Ancient Greek thought is that it was supremely intellectual and rational: the Greeks were into philosophy, not magic; Socrates went around annoying people by trapping them with logic, not by spouting revelations and prophecies. Like most clichés, this one has some truth in it. But Greek culture contained many elements that we would regard as non-rational. If you look into ancient literature, you don’t have to look all that far before you start finding mysticism and magic. And if you do start looking for this sort of thing, sooner or later you will run into the Chaldaean Oracles.[1] This is the most interesting Greek text that you’ve never heard of.

The Oracles survive only in fragments – that is, in quotations embedded in the works of other writers. Scholars have located as many as 227 of these. Their content is arcane and obscure. In part, they comprise philosophical revelations about the invisible nature of the cosmos; in part, practical guidance for magicians. An oracle is, of course, a message from a god. The Chaldaean Oracles accordingly claim to be the utterances of the gods themselves (and apparently also of Plato’s soul), although the divine communications seems to have been accompanied by some human commentary.

It has been suggested that the Oracles were obtained from their supposed divine sources through a process of clairvoyance, and that they are effectively notes of what we would today call séances. This idea was supported, notably, by E.R. Dodds, the great Northern Irish Classicist, who amused himself while off duty by taking an interest in the modern phenomenon of Spiritualism. (Dodds is the only person in history to have served simultaneously as Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford and President of the Society for Psychical Research.) The Oracles are written in hexameter verse, a poetic metre which was also used in other oracular texts, as well as (more famously) in epic poetry from Homer onwards.

The Oracles can be dated to the 2nd or perhaps the 3rd century AD. The dating depends, in part, on whether we see them as influencing or being influenced by the Platonist philosopher Numenius, who was active in the late 2nd century AD. It is generally thought that they were composed (whether or not through alleged clairvoyance) by a father and son team who were known as Julian the Chaldaean and Julian the Theurgist. It is difficult to say more about these enigmatic characters, except that they seem to have lived during the reign of the emperor Marcus Aurelius (AD 161–80).

‘Chaldaean’ means Babylonian, but in this context it is probably just a symbolic term meaning ‘mystical’ or ‘esoteric’ (compare how the Roma people – ‘Gypsies’ – are stereotypically associated with magic today). Nevertheless, even if the Oracles do not come from Babylonia, it is quite likely that they were composed in the Middle East. One suggestion for their place of origin is the town of Apamea in Syria, although this theory is controversial.

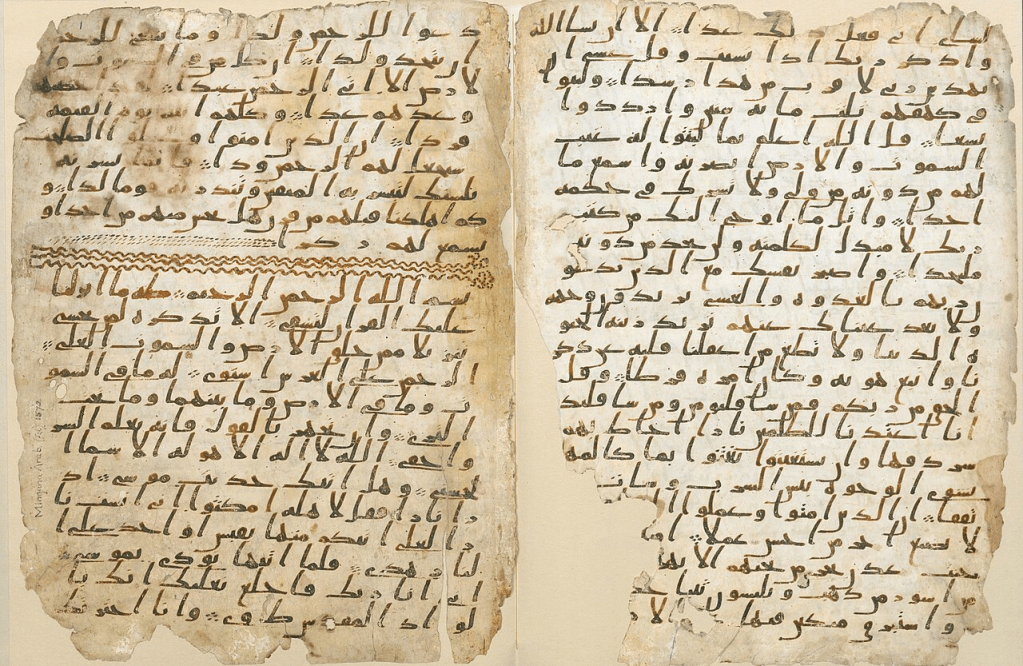

This, then, is a text which may come from the Middle East and which claims to transmit the literal words of the gods. If this sounds familiar, it should do. The Chaldaean Oracles are the closest thing that exists to a pagan Qur’an.[2]

If the text of the Oracles claims to be divine, its contents also reflect ideas that were current among human beings. As John Dillon, the great scholar of Platonism, wryly commented, “what is plain is that the Gods who spoke through Julian… were influenced themselves to some extent by contemporary Platonism.” And indeed the theories about the universe that are contained in the Oracles recognisably come from the tradition of Platonist philosophy (in what is known as its Middle Platonist phase).

The universe is presided over by three supreme entities, a kind of pagan Holy Trinity. There is the Father, or first Mind, who is the ultimate, perfect principle. Then there is an entity known as the second Mind or demiurge (creator). These two entities are linked by the Power of the Father, who may be identified with the goddess Hecate. There are hints that love is the principle of unity behind all things, coming down from the Father and the second Mind and residing in the human soul.

An important feature of the Oracles is that they appear to accept the basic Platonist idea that the physical world around us – the world that we can see and touch – does not represent the totality of the cosmos. There also exists a transcendent spiritual realm which is superior to the material world. The overall narrative of the human condition is that the spiritual human soul has descended into the material body; but if you have faith, truth and love in your heart you can re-ascend back upwards to the divine, with the help of magical rites.

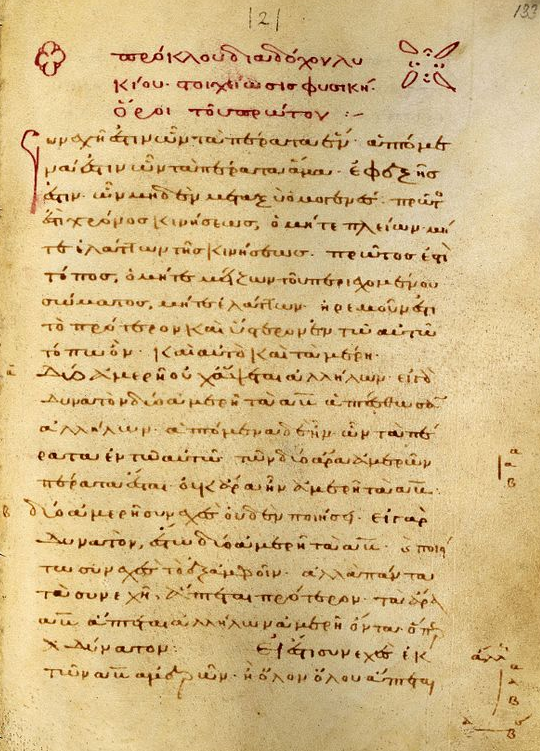

It is unsurprising that later Platonist philosophers were enormously impressed with the Oracles. This was the case, in particular, with the philosophers of the Neoplatonist school, which was active from roughly the 3rd to the 6th centuries AD.[3] The Oracles are sometimes referred to as “the Bible of the Neoplatonists”, a phrase popularised by the Belgian scholar Franz Cumont. The Neoplatonist philosopher Proclus said that, if he had his way, every old book in the world would be destroyed apart from the Oracles and Plato’s Timaeus.

Several Neoplatonists composed entire works (now lost) based on the Oracles; and most of the surviving fragments were transmitted, directly or indirectly, by two Neoplatonists, Proclus and Damascius. These people were pagans; but it is also worth noting that the Oracles influenced some ancient Christian writers, including those with Neoplatonist leanings (although Christians seemed generally less willing to engage with this body of material than pagans).

Strictly speaking, you should not be reading this article, because the Oracles are a text for initiates only: “keep silience, initiate” warns Fragment 132. Initiates were special people, distinct from the general “herd” of humanity (Fr. 153; see also 154). If you, like me, are a member of the herd, you will struggle to understand what the Oracles are trying to say, as they are not intended to be transparent to those unfamiliar with the mystical framework that they describe. Those outside the fold will not easily grasp the obscure doctrines of the Chaldaean system, and the initiates are not in a position to explain what the text means, or indeed what any text means, because they all died of old age many centuries ago.

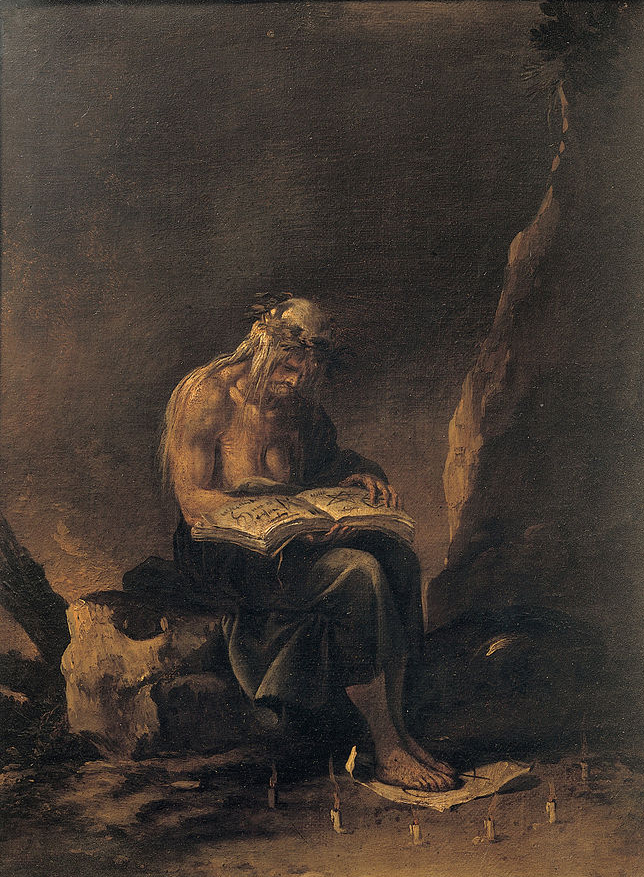

There are a few clues in the surviving fragments of the Oracles that indicate what the Chaldaean magicians got up to. Their rituals seem to have had something to do with meditating while inhaling sunlight, a practice that is also attested elsewhere in ancient mystical literature. There were other practical elements to the rites too. They may have entailed purification using sea-water. They involved something called the strophalos of Hecate, which was a magical spinning tool. Initiates were recommended to use a particular type of stone called Mnizouris.

When the mystical initiates performed their rites, they claimed to see visions and hear voices. The Oracles describe supernatural apparitions that were expected to appear to the ritualist. These seem to have included encounters with the goddess Hecate. One fragment indicates that the apparitions that an initiate might see could range from the vague – a bright light, or a shapeless fire that speaks words – to the highly specific – a naked golden child on horseback who is firing a bow. (Incidentally, it is curious how often fire is mentioned in the Oracles. This may indicate that they were influenced by the philosophical theories of the Stoics, who were very keen on fire.)[4] The Oracles also refer to the prospect of meeting dangerous apparitions, and tell the reader or listener how to repel them – that is what that mysterious Mnizouris stone was for.

Beyond this, there is something of a gap in what the Oracles are able to tell us about the rites that the initiates performed. The passage of time has kept the Chaldaeans’ secrets quite effectively.

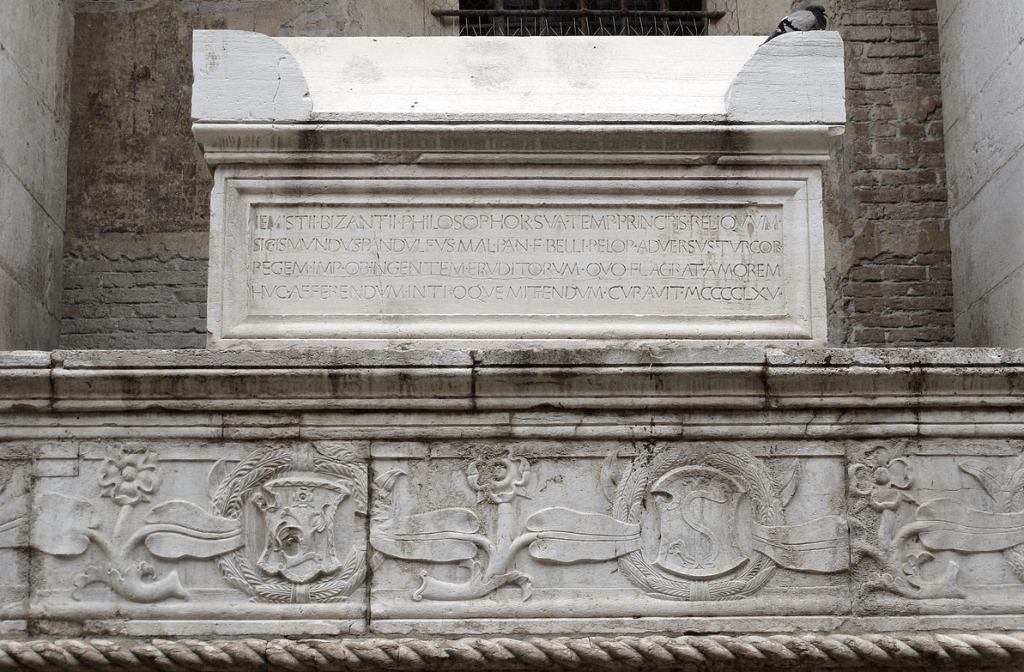

The Oracles have had a long afterlife. They were generally neglected in the Middle Ages, although were taken up in this period by two important Byzantine Greek scholars, Michael Psellus (1018–c. 1078) and George Gemistus Plethon (c.1355–1450/52), both of whom wrote commentaries on the Oracles. Plethon seems to have been the first person to connect them with the Persian prophet Zoroaster. The idea that their contents were revelations from Zoroaster became quite popular in later times, and served to mark them as an exceptionally early text containing special divine wisdom.

Plethon also appears to have been a key figure in introducing the Oracles to Western Europe. They became known in Renaissance Italy, and they had been translated into Latin by the 1460s. They were studied by the well-known Italian intellectuals Marsilio Ficino (1433–99) and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–94), both of whom had Platonist and esoteric interests. Some figures in this period looked to the Oracles as a witness to the truth of Christianity: for example, in their conception of the supreme divine power as a trinity. People in this camp include the Catholic scholars Agostino Steuco (1497–1548), Francesco Patrizi da Cherso (1529–97) and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486–1535); the French Protestant leader Philippe de Mornay (1549–1623); and the radical heretic Michael Servetus (c.1511–53).

The first vernacular translation of the Oracles – into French – appeared in 1558. As it happens, most of the early printed editions of the text were published in France, where Platonist philosophy was strong. An English edition did not appear until 1661, when one was published by the gentleman philosopher Sir Thomas Stanley (1625–78). As with their continental European predecessors, some English writers in this period looked to the Oracles to confirm the truth of Christian doctrines. These included the “Cambridge Platonist’ Ralph Cudworth (1617–88) and the Anglican bishop Richard Kidder (1633–1703).

From the 18th century, something new started to happen. Some people began to look to the Oracles as inspiration for revived varieties of pagan mysticism outside a confessional Christian framework. In this context, we might mention the English pagan Platonist philosopher Thomas Taylor (1758–1835); the esoteric American Freemason Albert Pike (1809–91); the Russian-American mystic Helena Blavatsky (1831–91); and the French magician and mystic Éliphas Lévi (1810–75).

Lévi took the significant step of using the text of the Oracles in magical rites; he was probably the first person to do this in modern times, but not the last. Fragments from the text were incorporated into the rituals of the highly influential Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an occult society which was founded out of esoteric Freemasonry in London in 1888. The Golden Dawn embraced a mixture of pagan and Christian ideas, and has had numerous successor orders, some of which remain in operation today. It also bears noting that the Oracles influenced the notorious occultist provocateur Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), who repeatedly quoted from them (for example, in his essay “The Herb Dangerous: The Psychology of Hashish,” which later became a hippy classic).

If this all seems a bit weird and abstruse, it bears noting that the Oracles have also been used by eminent creative writers of international reputation. Such figures have included the American transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82) and Henry David Thoreau (1817–62), as well as the great Irish poet and Nobel laureate William Butler Yeats (1865–1939).

Fragmentary, mystical and obscure, the Chaldaean Oracles have proved to be a source of fascination for numerous readers across the best part of two millennia. They have captured the attention of a disparate group of people ranging from ancient Platonist philosophers to Renaissance Christians to modern occultists. Their story is surely not over yet. Perhaps they will intrigue and inspire you too. Why not give them a read?

Robin Douglas is a writer based in London who specialises in the history of pagan, esoteric and other minority religious movements. His academic background is in Classics, and he has a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge. He has recently published a short book, Paganism Persisting, co-written with the historian Francis Young, to investigate the phenomenon of pagan revivals through European history; his previous article for Antigone was on this theme.

Further Reading

The standard edition of the Oracles, with a translation into English, was published by Ruth Majercik in 1989 and may be found online here.

It is also worth mentioning Hans Lewy’s classic treatise on the Oracles, Chaldaean Oracles and Theurgy (posthumously published in 1956), which may be found online here.

A series of academic studies of the Oracles have been published out of Heidelberg by Universitätsverlag Winter in the Bibliotheca Chaldaica series (general editor Helmut Seng).

Notes

| ⇧1 | Or, per American spelling, Chaldean Oracles. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | However, there were also other pagan collections of oracles, such as those compiled by Porphyry and Cornelius Labeo. |

| ⇧3 | For more information on Neoplatonism, see Pauliina Remes, Neoplatonism (Univ. of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 2008). |

| ⇧4 | For more information on Stoicism, see John Sellars, Stoicism (Routledge, London, 2014). |