Saga Herdeskoeld

“Modern English is full of roundabouts, of metaphors without meaning, verbiage, shams”, W.H.D. Rouse poignantly observed in 1911: “Greek and Latin are plain, direct, true”.). Why can’t English just be as straightforward as Greek and Latin?

The Roman author Aulus Gellius (AD 125–80) would retort that ignorance sometimes spoiled the straightforwardness of Latin. Ignorance about the exact meaning of words impedes a full understanding of the Aeneid. Written by Vergil (70–19 BC) and published posthumously, this poem is Rome’s pre-eminent national epic, narrating the journey of Aeneas and his fellow Trojan refugees as they flee the fall of Troy to the Greeks. The poem culminates with the Trojans’ obtaining – through war and treaty – their divinely-sanctioned rule in Italy. Gellius discussed the Aeneid on several occasions in his miscellaneous work of learned scholarship Noctes Atticae (Attic Nights).

Gellius’ examinations of two particular Vergilian terms – bidens (“two-toothed animal”) and iapyx (which in English is a mouthful: “a wind blowing from the Italian region of Apulia”) – testify to his thirst for learning. In addition to allowing the reader a glimpse into the mind of the author himself, these discussions reflect his unusual intellectual environment.

Gellius wrote during what is often called the ‘Antiquarian Movement’. As the name hints, the Antiquarian Movement favoured the preservation of old knowledge. Antiquarian intellectuals scrutinised literature to compose compendia of etymological knowledge, of which Noctes Atticae is one of the most prominent examples. These compendia helped the reader participate in learned discussions, usually around the dinner table.[1] Detailed linguistic examinations were nothing new in Roman or Greek culture, however; perhaps the most notable cases can be found in the surviving works of Varro (116–27 BC). Similarly, Cicero (106–43 BC) had made the definition of terms a prerequisite for philosophical discussion,[2] itself reflecting the persistent custom of Socrates (469–399 BC).

A major factor that helped shape the Antiquarian Movement in the 2nd century AD was the oppressiveness of the imperial state, perhaps most notably under Nero (r. AD 54–68) and Domitian (r. 81–96). The relative liberty established by Nerva (r. 96–8) and Trajan (r. 98–117) prompted a tendency to repudiate literature of this era. Imperial censure had been overcome, but the very vigour of the language seemed to have been sapped, and the deeper meanings of words appeared all but eviscerated. These features contributed to a general desire to reconnect to the Roman past by reconnecting to an older, sterner, more austere literature. Also, the emperor Hadrian (r. 117–38) showed great interest in Classical learning, which spurred the elite to align their interests with the newfound imperial sophistication.[3]

Classical erudition focused on the Greek intellectual tradition, but the audience for antiquarian works remained Roman. While Greek sophists lectured to public audiences, Latin antiquarians did not aim at performing publicly, instead letting their works circulate among high-brow readers, directing attention, not toward themselves as charismatic speakers, but towards pure knowledge.[4] Ancient students typically learned about Classical works by what we today would probably call directed reading – that is, by reading together with a teacher and asking questions.[5] The main teacher – or intellectual ‘hero’ – in Noctes Atticae will emerge to be one Favorinus.

It might not come as a surprise that antiquarian literature often exposes and ridicules pseudo-intellectuals. Revelations of pseudo-intellectualism have a distinguished history in ancient literary traditions, as is evident from Aristophanes’ (450–388 BC) attack on Socrates in the Clouds.[6] What does Gellius tell us about fraudulent intellectuals? He hints at his own definition by means of an anecdote.

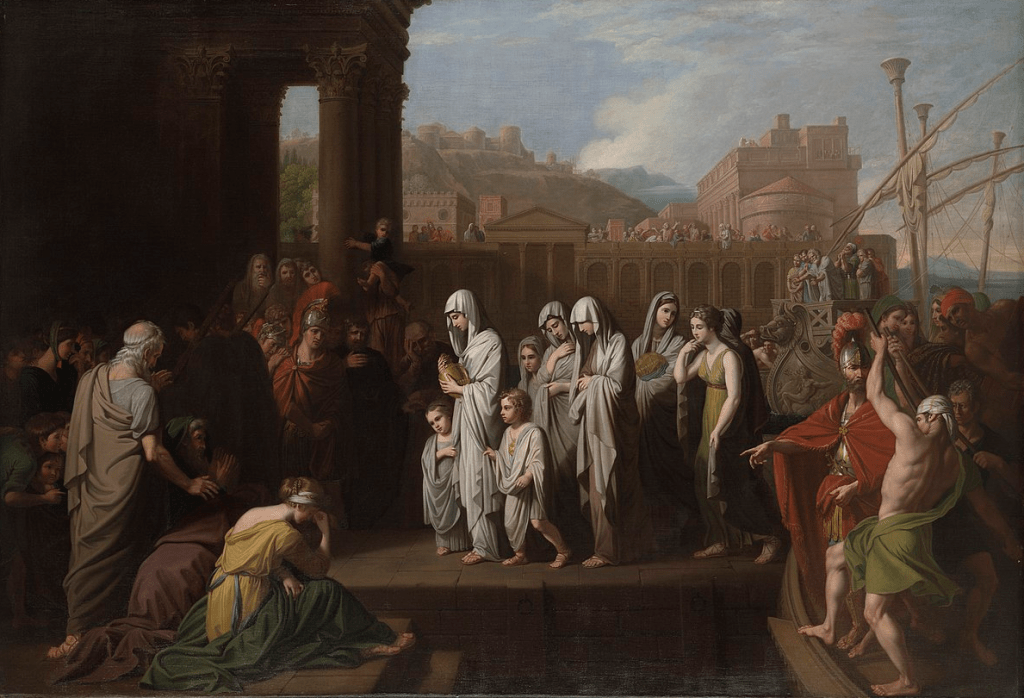

One day, when sailing from Greece to Italy, Gellius stopped at the Italian town of Brundisium to rest. There, he learned that a scholar from Rome was offering a public reading of the seventh book of Vergil’s Aeneid, followed by a question-and-answer session. Gellius joined the audience but instantly heard the scholar read Vergil, as Gellius puts it, “barbarously and ignorantly” (barbare insciteque). Gellius was amazed by the man’s self-confidence and decided to ask him a question: why did Vergil call sacrificial animals bidentes (“two-toothed creatures”)? The reply was swift and direct: bidentes is a synonym for “sheep”, which Vergil makes clearer by describing them as ‘woolly’ (lanigeras).

Gellius, obviously playing dumb, asked if the poet Pomponius erred when one of his characters promised Mars a two-toothed swine – not something obviously ovine. So bidens is clearly not synonymous with “sheep”, after all. Gellius continued by asking for the reason behind the word. The scholar, apparently ignoring Gellius’ mention of the swine, quickly replied that sheep are called bidentes because they only have two teeth. Gellius asked where on earth he had seen the portentous sight of a sheep with only two teeth. At this point, the scholar lost his temper with Gellius and told him to ask questions that ought to be put to a grammarian (grammaticus), and save queries about the teeth of sheep for shepherds (opiliones). Gellius laughed and concluded that the man was a nebulo, which in English would be rendered roughly as “wretch” or “rascal”.

It might be noted that nebulo is very similar to nebula, which means “cloud” and happens, perhaps quite unintentionally, to recall Aristophanes’ Clouds. Perhaps equally unintentional, but similarly worthy of note, is that Gellius’ laugh is the kind of reaction that one would expect from a spectator of comedy.

The reader can imagine himself rejecting the pseudo-intellectual alongside Gellius while awaiting his correct explanations for the word. First of all, Gellius says, Nigidius Figulus (a celebrated scholar) wrote that all sacrificial animals originally were called bidennes, which was changed to bidentes for smoother pronunciation. Second, Hyginus explained in the fourth volume of his study on Vergil that sacrificial animals should have eight teeth, of which two ought to be more prominent in order to show that the sheep had grown out of infancy.[7] A subsequently influential commentator on Vergil, Servius (fl. 400 AD), can help us understand why this is important. It was not allowed, Servius explains, to sacrifice a sheep younger than, or older than, two years old. Only sheep that are two years old have two prominent teeth, so they are the only ones that should be sacrificed.[8]

A 19th-century commentator, John Conington, quotes another helpful explanation to the effect that sheep, by the age of one, have two teeth which are so prominent compared to those behind them that they appear only to have two. Once these sheep have completed their second year, two more prominent teeth appear, such that they too have four, so cease to be bidentes.[9] Hyginus, Servius and Conington do not seem to align perfectly here; Gellius dismisses judgement by stating that the veracity of Hyginus’ claim can “be judged by the eyes” (NA 16.6.), which may be easier said than done.

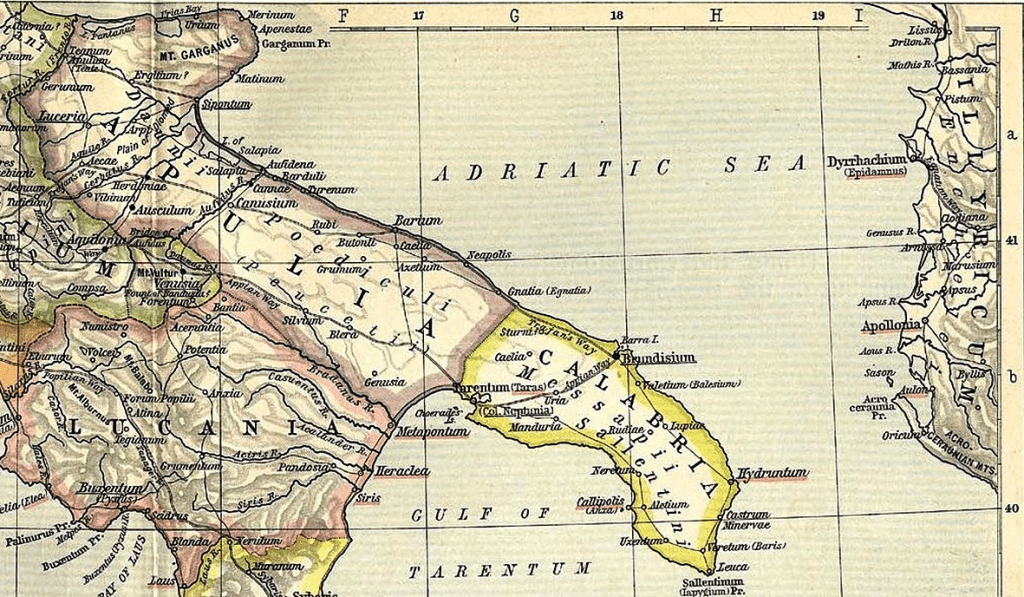

And now to the iapyx chapter. Here Gellius attends a dinner at Favorinus’ house. While they eat, they listen to a poem in which the rare word iapyx occurs. Questions arise around the table as to which wind this is and what its abstruse name means. They also ask Favorinus to tell them about the names and regions of the other winds. He explains that there are local winds that get their names by the people of the regions from which they blow. The Apulians call the wind that blows from Apulia iapyx because they as a people are known as Iapygias (or similar). Therefore, Vergil says that Cleopatra was carried by the iapyx to Egypt, and calls a horse “Iapygian” to refer to its Apulian origin (NA 2.22; Aen. 8.709–10; 11.677–8).

There are natural reasons why both bidens and iapyx might be misunderstood. Sheep can appear to have only two teeth, while the word iapyx is so rare that not even the erudite reader always know what it means. The scholar at Brundisium acts like a sophist by showcasing his supposed erudition publicly. It is easy to get the impression that Gellius asks him about bidens precisely because he knows that a pseudo-intellectual would be likely to respond that such a question should not be posed to a grammarian, whereas Gellius, demonstrating his characteristically antiquarian interest in details and etymology, thinks that this is indeed something that a scholar should know – and something that he himself obviously knows.

Gellius does not know what iapyx means, so he would not have been able to offer a perfect public reading of Vergil himself – but the difference between them is that Gellius does not attempt to. He realises that the scholar of his anecdote is a pseudo-intellectual because he reads barbarously.

Perhaps there is a further hint here about the man from Brundisium’s status: let it be remembered that Roman antiquarians tended not to put their knowledge on display as public speakers. In some sense, the scholar in the anecdote has failed as a Roman. It might also be noted that the two authors whom Gellius refers to, Nigidius and Hyginus, seem to highlight two of the scholar’s faults. Nigidius wrote that the term bidentes had evolved from bidennes for pronunciational smoothness. Yet smoothness of pronunciation and euphony are not the scholar’s strong sides – Gellius picks up on this particular defect simply by listening to him reading. Hyginus, in turn, explained that sacrificial animals should have two prominent teeth. Instead of demonstrating knowledge that sheep with two prominent teeth are, as Servius notes, the only ones that should be sacrificed, the scholar almost sacrilegiously says that all sheep have two teeth, possibly demonstrating impiety toward the gods.

Unlike the pseudo-intellectual of Gellius’ anecdote, Favorinus is a true intellectual. Instead of having the temerity to perform flamboyantly in front of a crowd, however, Favorinus demonstrates his erudition only when invited to do so by his gentlemanly friends during a private dinner. While the scholar explains bidentes by lanigeras – ‘woolly’ – which is from the same verse, Favorinus not only knows what iapyx means, but is also able to discuss other winds, and thus to put iapyx in a broader context, applying a range of relevant knowledge, and thus demonstrating a more profound understanding of the Aeneid and the world in which Vergil wrote. He shows that it is indeed profitable to be acquainted with facts and minutiae that at first glance might seem unrelated to Vergilian studies. Knowledge about the teeth of sheep evidently falls into this category too.

Gellius either instructs the reader, or else is instructed alongside him. Another thread running throughout the Noctes Atticae involves serious discussions about the relevance of knowledge. Perhaps the work’s greatest value lies precisely in the questions it raises about how and when knowledge should be applied. The Noctes Atticae can perhaps even be read as a subtle, wide-ranging and extended discussion about what knowledge essentially is. The central and enduring importance of that question is what makes Gellius a timeless companion.

Saga Herdeskoeld is a senior Bachelor’s student in Classics at the University of Gothenburg. She has previously published in The Christian Century on ancient reception in Voltaire’s essay “Religion“.

Further Reading:

John Conington, “Notes: Exquirunt,” in The Works of Vergil (3 vols, Whittaker & Co, London, 1858–72).

Thomas Habenik, “Was there a Latin Second Sophistic?,” in W.A. Johnston & D.S. Richter (edd.), The Oxford Handbook of the Second Sophistic (Oxford UP, 2017) 25–37.

Leofranc Holford-Strevens, Aulus Gellius: An Antonine Scholar and his Achievement (Oxford UP, 2003).

Wytse Keulen, “Gellius, Apuleius, and satire on the intellectual,” in L. Holford-Strevens & A. Vardi (edd.), The Words of Aulus Gellius (Oxford UP, 2004) 223–46.

Andrew Stevenson, “Gellius and the Roman antiquarian tradition,” in L. Holford-Strevens & A. Vardi (edd.), The Words of Aulus Gellius (Oxford UP, 2004) 118–56.

Notes

| ⇧1 | See further Holford-Strevens (2003) 8. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Stevenson (2004) 124–5. |

| ⇧3 | Holford-Strevens (2003) 1–2, 4. |

| ⇧4 | Habenik (2017) 35. |

| ⇧5 | Stevenson (2004) 125. |

| ⇧6 | See further Keulen (2004) 231. |

| ⇧7 | Noctes Atticae 16..6, where the scholar reads Aen. 7.93. |

| ⇧8 | So Servius, ad Aen. 4.57 |

| ⇧9 | Conington (1876) ad Aen. 4.57. |