Dobrinka Chiekova

From Rags to Riches

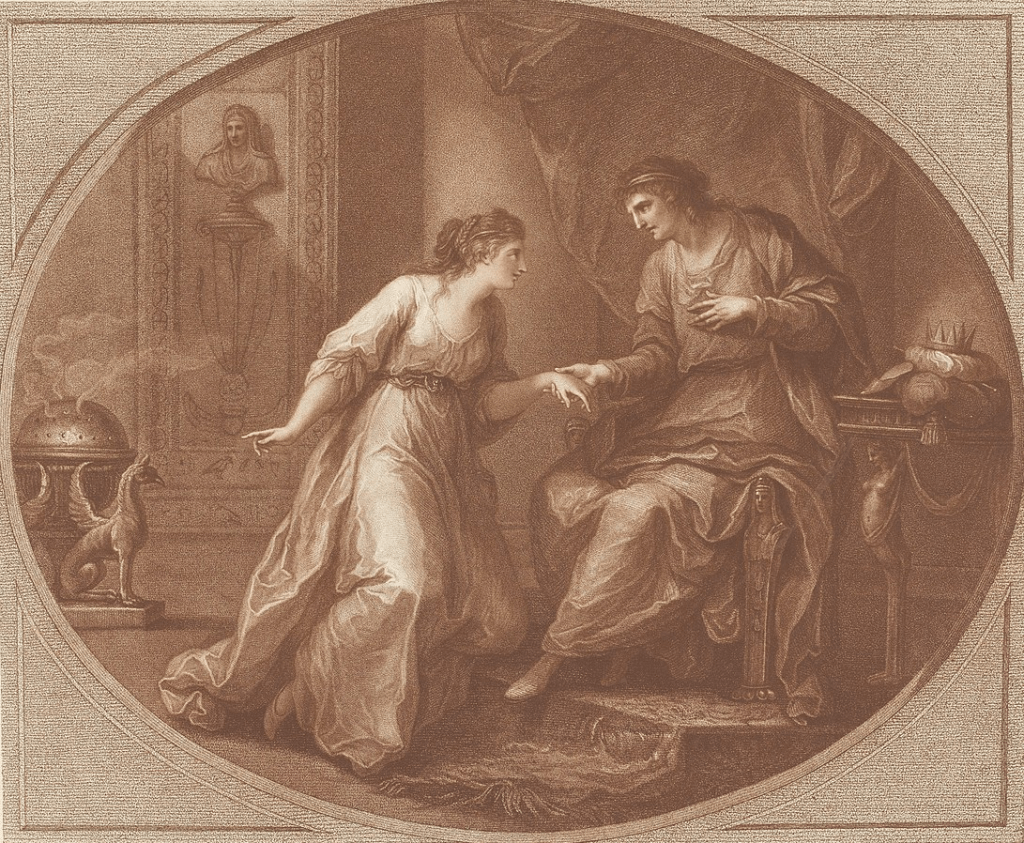

Once upon a time, on the island of Samos in the Aegean Sea, not very far from the great temple of Hera, lived a slave-girl by the name of Doricha. She was brought there from her native Thrace together with other men, women and children, and sold to a man called Iadmon. Doricha was smart and beautiful, and turned out to be a lucrative possession for Iadmon, who sold her for a good sum of money to a merchant named Xanthes. Her new master took her across the sea to Egypt, where he would sell her repeatedly to wealthy clients for their entertainment and pleasure.

The city of Naucratis, where Xanthes brought Doricha, was a thriving trade hub located on Nile Delta. Naucratis has been ceded to the Greeks by the pharaoh Psammetichus I (664–610 BC), and was initially founded by Ionians from Miletus. It fast became a magnet for merchants from all over Greece who brought in their goods (especially silver and wine), and carried back Egyptian goods – primarily corn, but also linen, papyrus and faience-ware objects. The fame of her beauty grew in a city which was already famous for its brothels and courtesans. Many of her lovers were among the leading Egyptians and Greeks. One, by the name of Charaxus, son of Scamandronymus, a merchant from Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, fell in love – or was it an infatuation? – and offered Xanthes a great sum of the money to buy Doricha’s freedom.

After becoming a free woman, Doricha continued to practise her profession in Naucratis as an intimate companion (hetaira) to noble and wealthy clients. What else could have she done? It was not as though anyone was going to marry her and make her a respectable housewife. She was known now by the nickname of Rhodopis (Rosy-face) and became wealthy; her famous beauty was celebrated across the Greek world in songs performed at the drinking parties (symposia) of aristocratic men. In fact, Doricha-Rhodopis became so prosperous that, wishing to leave a praiseworthy monument, she used one tenth of her wealth to commission a set of large iron spits, which she dedicated in the temple of Apollo at Delphi, the most prestigious of all Ancient Greek sanctuaries. Long after her death, a rumor persisted that, in imitation of the pharaohs, she even built a pyramid for herself.

Charaxus returned to the island of Lesbos. His sister, the famous poetess Sappho, wrote a poem attacking and ridiculing him for foolishly wasting the family’s money on a courtesan, which sealed Rosy-face’s fame among both her contemporaries and future generations. Whoever attracted the attention of the “Tenth of the Muses”, as Sappho was (allegedly) described by Plato, was bound to leave a lasting memory, even if she only inspired a reprimand.

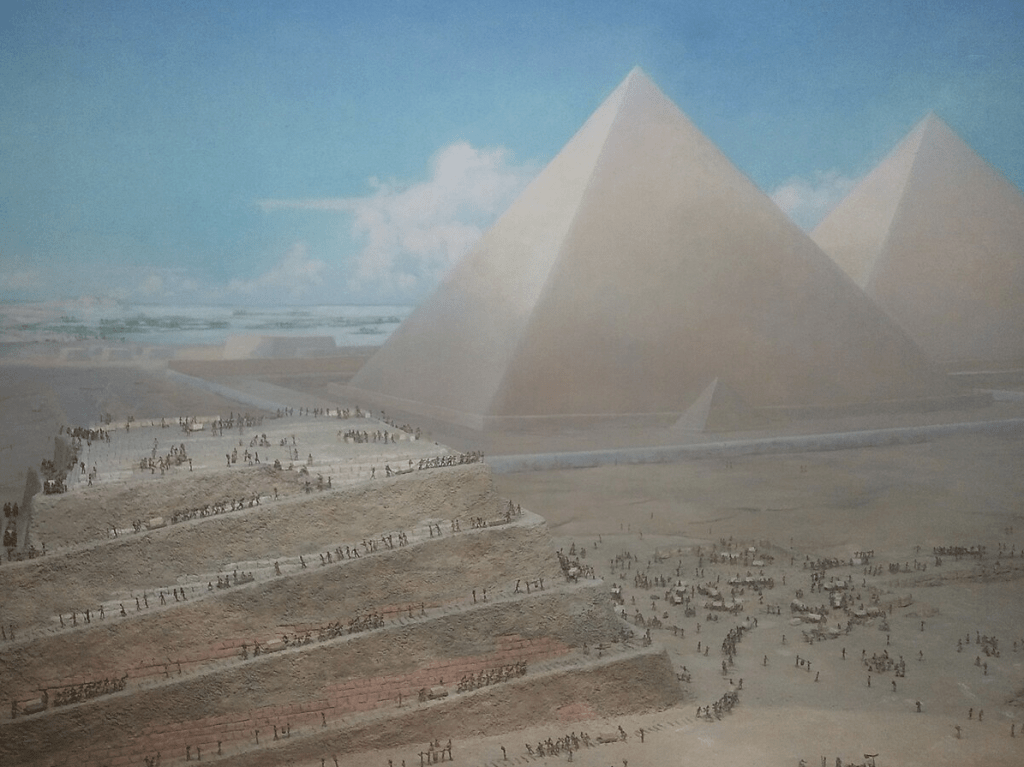

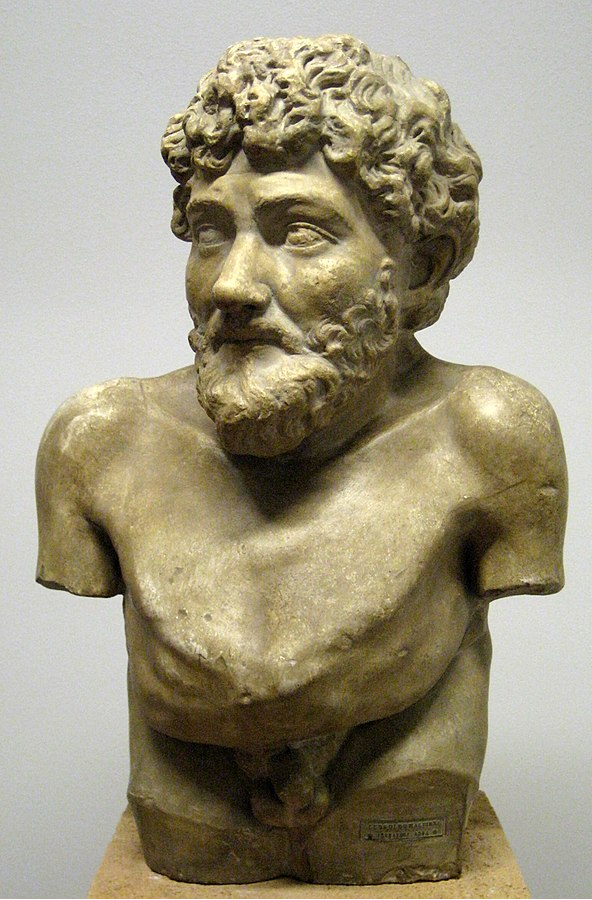

So is this story true? On some level, and in some respects, probably yes; in others, probably not. Our principal, best-known source is Herodotus (c.484–420s BC), both “the father of history” and “the father of lies”. In Book 2 of his Histories he describes the geography, flora, fauna, and the millennia-old civilization of Egypt. In the section where he gives an account of the pyramids of modern-day Giza – which looked as astounding and wondrous an achievement to the ancient observer as they still do to us today – and of the reign of the pharaohs of the Fourth dynasty who built them – Cheops (ruled c.2596–2573 BC), Chephren (c.2472–c.2448) and Mycerinos (c.2472–c.2448) – Herodotus includes the intriguing story of a famous Thracian courtesan by the name of Rhodopis who lived in the Greek trading enclave of Naucratis.

Herodotus’ Story (Book 2, 134–6)

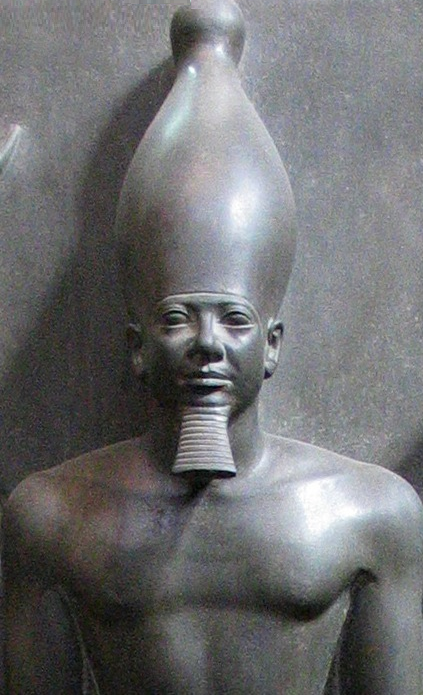

Mycerinus also left a pyramid – a good deal smaller than his father’s – each side of whose square base is 280 feet long, and whose lower half is fashioned out of Ethiopian stone. This is the same pyramid which some Greeks say was built by Rhodopis, who was a courtesan; but they are quite wrong in that particular claim. In fact, it seems to me that such a theory displays a complete ignorance as to who Rhodopis actually was; had they known, its proponents would never have attributed to her the construction of a pyramid on such a scale, and which, it is hardly an exaggeration to say, must have cost thousands upon thousands of talents, beyond the ability to count. What is more, Rhodopis flourished during the reign of Amasis, long, long after the age of the kings who left the pyramids to posterity, and not way back in the time of Mycerinus.

Rhodopis herself was Thracian by birth; she was owned by a man from Samos called Iadmon, the son of Hephaestopolis, who was also the master of Aesop, the fabulist. The clearest proof that Aesop was a slave of Iadmon is what happened when the Delphians, prompted by Apollo, repeatedly announced that anyone who so wished could claim the blood money from them that was owed following Aesop’s murder. Not one person came forward until Iadmon’s grandson, who had the same name as his grandfather, laid claim to it – certain proof that Aesop did indeed belong to Iadmon.

It was in the train of Xanthes, a Samian, that Rhodopis came to Egypt. Here, following her arrival, she was set to work; until, at immense cost, she was redeemed from slavery by a man from Mytilene called Charaxus, the son of Scamandronymus and brother of Sappho the poet. Rhodopis, having been freed, stayed on in Egypt, where such was the potency of her sexual allure that she ended up exceedingly wealthy – or rather, I should say, exceedingly wealthy by the standards of the kind of woman that she was, but not so wealthy as to be able to afford a pyramid like that of Mycerinus.

There is certainly no point in ascribing great wealth to her – not when it is possible for all those who fancy it to go and see what a tenth part of her estate actually comprised. Rhodopis’ ambition, you see, was to leave behind a memorial to herself in Greece, an offering such as no one else had ever thought to make and present to a shrine, and which she looked to dedicate to Delphi, to keep her memory alive there. So she spent a tenth part of her fortune on having ox-roasting spits of iron made for her – as many of them as her tithe could buy her – and send them all to Delphi.

There they still are to this day, piled up in a heap behind the altar which the Chians dedicated, opposite the temple itself. It is a strange thing, but the courtesans of Naucratis have always had a talent for making themselves sexually irresistible. In addition to the courtesan who is the subject of this current passage – the one who became so famous that every Greek is familiar with the name ‘Rhodopis’ – there is also a more recent one, Archidice by name, who, despite lacking the all-round celebrity of her counterpart, nevertheless figures in songs far and wide across the Greek world. Charaxus, after he bought Rhodopis her freedom, returned home to Mytilene, where he was roundly mocked by Sappho in one of her poems. But that is enough about Rhodopis.” (trans. Tom Holland; for the Greek text, visit here.)

Herodotus is compelled to mention Rhodopis in this context because he is appalled and bemused by the claim made by “some Greeks” (as he anonymously refers to the authors of the baseless report) that the smallest of the three pyramids (of Giza) was built by Rhodopis. The famous courtesan, Herodotus retorts, was a wealthy woman, but not at the level of a pharaoh to afford building a pyramid for herself. Moreover, he asserts, she lived in the 6th century BC during the reign of Amasis (pharaoh of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, who ruled from 570 to 526 BC) – thousands of years later than the kings who built the pyramids he had just described (the kings of the Fourth Dynasty, according to the chronology of the 3rd-century BC Egyptian historian Manetho).

Later Greek sources, namely Diodorus of Sicily (1st century BC), Strabo (c.64 BC–AD 21), and Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79 AD) allude rather less critically in their descriptions of the pyramids of Giza to the report which attributes the third pyramid to Rhodopis. Diodorus lists three possible candidates for the building of the smallest pyramid, including the story that lovers of the courtesan Rhodopis, identified as governors of the provinces (nomes) of Egypt, joined forces to complete it.[1] Strabo, for his part, incorporates an additional curious anecdote according to which, when Doricha (also called Rhodopis, he tells us) was bathing in a river, an eagle snatched her sandal from the attendant’s hands, then flew all the way to Memphis and dropped it in the Egyptian king’s lap. The king was captivated by the elegant shape (rhythmos) of the sandal and astonished by the way it was delivered and subsequently sent people across Egypt to look for his ‘Cinderella’. After finding Rhodopis in Naucratis, he made her his wife, and later built the third pyramid to honor her memory.[2]

A strikingly similar story features in Herodotus’ narrative only a couple of paragraphs above the story of Rhodopis (Histories 2.126), this time of an Egyptian princess turned courtesan who built a pyramid for herself. The pharaoh Cheops, the builder of the Great Pyramid, was such a wicked man, Herodotus declares, that when he needed more money to complete his colossal project, he forced his daughter to prostitute herself. She did what her father demanded but, wishing to leave a monument for herself, asked each of her lovers to give her a stone in addition to the money; of these gifts she built a small pyramid for herself next to her father’s.

The building of the third pyramid of Giza had been attributed by the Egyptian historian Manetho to a queen of the Sixth Dynasty by the name of Nitōkris, who ruled towards the end of third millennium BC. Modern scholars have suggested that the building of the pyramid was started by the pharaoh Mycerinos of the Fourth Dynasty (probably son of Cheops not Chephren, as Herodotus claims), and it was finished by the female pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty some centuries later.

Gregory Nagy, in an article published by Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, interprets the Greek story about Rhodopis as a variation on traditional Egyptian narratives of a queen or princess turned courtesan who builds a pyramid or vice-versa – a courtesan turned queen who is honored with a pyramid. He points out that Manetho, who wrote in Greek, describes the Egyptian queen Nitōkris as “fair in complexion” (xanthē chroia), and argues that the story of the remarkable queen, who in the Armenian translation of Eusebius of Caesarea is portrayed in Latin as flava rubris genis (‘blonde with blushing cheeks’), might have been a traditional Egyptian theme that served as model of describing as ‘Rosy-faced’ the beautiful Thracian courtesan in the cosmopolitan emporion (trading station) of Naucratis a millennium and a half later, and also crediting her with pyramid-building. W.W. How and J. Wells, in their Commentary on Herodotus, mention a modern Arab tale in which the third pyramid was haunted by a beautiful naked woman who drove men mad; this might indeed be a relic of a very old tradition.

The tale of the seductive sandal, Strabo’s fanciful embellishment of Rhodopis’ biography, probably also belongs to Egyptian traditional lore, but Herodotus pleads ‘not guilty’ for this late addition, even if it parallels his own emphasis on sensual charisma and a path leading from poverty and powerlessness to luxury and privilege.

Returning to our story, we should unequivocally affirm with Herodotus that it is ludicrous to claim that the third pyramid of Giza was built by or in memory of Rhodopis who lived in the 6th century BC in the city of Naucratis.

Doricha-Rhodopis, Aesop, and Sappho

But what about the rest of Herodotus’ tale? Was Rhodopis a fellow slave of Aesop, the maker-of-stories (logopoios)? Again, it is sadly impossible to corroborate this claim. Indeed, scholars doubt the very historical existence of the legendary author of “The Hare and the Tortoise”, “The Fox and the Grapes” and hundreds of other famous fables that were ascribed to him in antiquity. ‘Aesop’, mentioned as a real person by Herodotus, as well as by other 5th/4th-century sources such as Aristophanes and Plato, seems to have become in antiquity a generic name-designation of authorship for a particular literary genre, the didactic animal story.

In the Ancient Greek tradition, Aesop was imagined as a non-Greek (Thracian, Phrygian, Aethiopian) slave, very ugly and possibly mute, yet clever and resourceful enough to win his own freedom. These characteristics make it easy to imagine him as the founder of the witty but common and pedestrian genre of the fable. His rise from humble beginnings to success and celebrity parallel the life story of Doricha-Rhodopis.

Even a more fascinating question posed by Herodotus’ passage is whether Charaxus, the brother of Sappho the poetess (mousopoios), was indeed the lover of Rhodopis who spent a fortune to buy her freedom and thus annoyed his brilliant sister to the point of inspiring her to compose (wrathful) poetry. Herodotus’ reference to the seafaring career of Charaxus seems to be confirmed by the newest fragment of Sappho’s poetry, published in 2014 and known as “The Brothers Poem”, in which the names of Charaxus as well as his and Sappho’s younger brother Larichus appear. The poem conveys Sappho’s anxiety for Charaxus’ safe arrival in harbor after a sea voyage:

ἀλλ’ ἄϊ θρύλησθα Χάραξον ἔλθην

νᾶϊ σὺν πλήαι. τὰ μὲν̣ οἴο̣μα̣ι Ζεῦς

οἶδε σύμπαντές τε θέοι · σὲ δ’ οὐ χρῆ

ταῦτα νόησθαι,

ἀλλὰ καὶ πέμπην ἔμε καὶ κέλεσθαι

πόλλα λί̣σσεσθαι̣ βασί̣λ̣η̣αν Ἤ̣ραν

ἐξίκεσθαι τυίδε σάαν ἄγοντα

νᾶα Χάραξον…

Oh, not again – ‘Charaxus has arrived!

His ship was full!’ Well, that’s for Zeus

And all the other gods to know.

Don’t think of that;

But tell me, ‘go and pour out many prayers

To Hera, and beseech the queen

That he should bring his ship back home

Safely to port’… (trans. C. Pelling & M. Wyke)

In Herodotus’ rendering Charaxus is a supporting actor in a film in which the star is Rhodopis. His name was worth mentioning only because he was the brother of Sappho and because she (allegedly) later admonished and mocked him (κατεκερτόμησέ μιν, katekertomēse min) in her poetry. To date, the name Rhodopis doesn’t appear in any available fragments of Sappho’s poems. However later sources inform us that a hetaira named Doricha was berated by Sappho in her poems. This name has been conjecturally restored in Fragment 15 and, less certainly, Fragment 7 of her poetry.

Fragment 15

… blessed one …

… [goddess] of good sailing …

*

*

[and may he undo his past] mistakes

*

… [with] fortune … [harbor] …

*

May Doricha find you most bitter, Aphrodite,

and may she not boast, saying

she came the second time

to longed-for love. (trans. D. Rayor)

Fragment 7

[Doricha] …

… urges, since no …

*

… to reach … arrogance

… to be like young men

… [friends] (trans. D. Rayor)

An article by Giulia Donelli makes a good case,[3] even if necessarily a hypothetical one, that another fragment, [4] which does not contain the name Doricha but expresses negative feeling towards an unnamed female addressee, might as well be dedicated to the irritating (in Sappho’s eyes) woman who separated her brother from his hard-won money.

Athenaeus from Naucratis (2nd century AD) cites an epigram dedicated to Doricha by Posidippus of Pella, a Hellenistic poet of the 3rd century BC, which mentions Sappho’s poetic invectives:

Posidippus also made this epigram on Doricha, although he had often mentioned her in his Ethiopia, and this is the epigram:

“Here, Doricha, your bones have long been laid,

Here is your hair, and your well-scented robe:

You who once loved the elegant Charaxus,

And quaff’d with him the morning bowl of wine.

But Sappho’s pages live, and still shall live,

In which is many a mention of your name,

Which still your native Naucratis shall cherish,

As long as any ship sails down the Nile.” (Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, 13.69; trans. C. D. Yonge; for the Greek text, see here.)

Ovid, in his imaginary letter written by Sappho to her unfaithful beloved Phaon (Heroides 15), [5] also includes a lament regarding her brother’s scandalous behaviour:

arsit iners frater meretricis captus amore

mixtaque cum turpi damna pudore tulit;

factus inops agili peragit freta caerula remo,

quasque male amisit, nunc male quaerit opes.

me quoque, quod monui bene multa fideliter, odit;

hoc mihi libertas, hoc pia lingua dedit. (Her. 15.63–8)

My untaught brother was caught in the flame of harlot love, and suffered loss together with foul shame; reduced to need, he roams the dark blue seas with agile oar, and the wealth he cast away by evil means once more by evil means he seeks. As for me, because I often warned him well and faithfully, he hates me; this my candour brought me, this my duteous tongue. (trans. G. Showerman)

But were Doricha, mentioned by some sources and in Sappho’s Fragment 15 and 7, and Herodotus’ Rhodopis, the same person? Opinions differ, today as in antiquity. Strabo tells us that it was “the tomb of a courtesan, built by her lovers, and whose name, according to Sappho the poetess, was Doricha. She was the mistress of her brother Charaxus, who traded to the port of Naucratis with wine of Lesbos. Others call her Rhodopis.”[6] How and Wells, and Alan Lloyd, in their commentaries on Herodotus’ Histories, accept that Rhodopis is a nickname of Doricha. Others prefer to follow Athenaeus, who claims that Herodotus was wrong to confuse the two courtesans from Naucratis, and that Charaxus was the lover of Doricha not Rhodopis (Deipnosophists 13.69).

The more economical solution, it seems to us, would be to trust Herodotus until he is proven wrong, and to suppose that in Naucratis during the 6th century BC there was only one courtesan with whom Sappho’s brother was head over heels in love, and who was mentioned unfavorably in his sister’s poems; she was called Doricha but was better known by the nickname Rhodopis.

The Delphic Offering

Another remarkable and puzzling element in Herodotus’ story concerns the dedication made by Rhodopis in the Delphic sanctuary of a tenth (dekatē) of her fortune in the form of a set of giant iron spits for the roasting of sacrificial oxen (obelous bouporous). The historical reality of the dedication is confirmed by Athenaeus,[7] as well as Plutarch.[8] Additionally, an inscription from Delphi containing the letters ΚΕΡΟΔ in the Phocian script, and dated to the second half of the 6th century BC (after 540 BC), has been tentatively restored by L.H. Jeffery, and accepted by other epigraphists, as a dedication made by Rhodopis that was inscribed on the base where the iron spits were placed: [· · ? · · ἀνέθε]κε Ῥοδ[ο͂πις] [· · ? · ·], “Rhodopis dedicated”.[9] As plausible and exciting as the prospect is, the document needs too much modern supplementation to be unreservedly accepted as genuine physical evidence connecting us to the famous courtesan.

The historicity of the offering itself, however, has not been called into doubt by scholars, even if many have wondered why a low-status individual such as a Naucratian hetaira would dedicate this specific offering, displayed in one of the admittedly most prominent locations (next to the Altar of the Chians) within the most prestigious Greek sanctuary. Herodotus states that Rhodopis wanted to commission something which “no-one else had ever thought to make and present to a shrine and which she looked to dedicate to Delphi”. This qualification is surprising, because iron spits were not an uncommon dedication in sanctuaries in this period. Herodotus and his Greek audience must have known this.

However, Herodotus’ expression may simply imply that Rhodopis carefully considered her sacred gift, and that it was meaningful to her. But what was the meaning of Rhodopis’ offering? Jeffery proposes that the iron spits in a pre-monetary economy express the value of currency; [10] Leslie Kurke suggests that her motivation was “to insert her gift completely into a sacral economy of sacrifice”, and that the offering implies a “circumscribed, elite context”.[11]

There might be yet another explanation, even if (again) it can be offered only as a hypothesis.

Doricha/Rhodopis, we recall, was Thracian. On several scenes painted on Greek vases that depict the death of Orpheus, spits (together with stones, double axes, and harps) appear in the hands of the Thracian women who attack and dismember the divine musician in some versions of the Orpheus myth.[12] Only the prophesizing head of Orpheus is carried by the sea to the island of Lesbos. Why do these Thracian women attack and dismember Orpheus? We say “women” because on some vases Thracian men are depicted as merely observing the assault. The mythological explanations vary: they are either sent by Dionysus to exact revenge (on the grounds that Orpheus is a devotee to Apollo and failed to honor Dionysus), or else they are angry that he steals their men away from them with his enthralling music.

Apart from his reputation for being a godlike musician, ‘Orpheus’ was also known in antiquity as an archetypal religious teacher, and the author of a special type of ‘Orphic’ poetry, which was concerned with the origins of the universe (cosmogony), the gods (theogony), and men (anthropogony), as well as the afterlife (eschatology). Orpheus was further thought of as the proponent of secret (mystery) rites interrelated with Dionysian (Bacchic) worship. The debates and disagreements among scholars surrounding Orphism and Orphic literature are too complex to be summarized here, but the ‘Further Reading’ section below provides the reader with some starting points should s/he wish to dive down into this fascinating rabbit hole.

Another mythical story which parallels the dismemberment of Orpheus by Thracian maenads, and is also associated with Orphic teachings – and which might have a bearing on our story – is the myth of Dionysus-Zagreus. The different components of this myth have been assembled from a variety of ancient sources that span hundreds of years, from (probably) the Classical period to Late Antiquity. Here are some of the main elements of the Zagreus myth:

Zagreus (identified as a form of Dionysus) is born from the union of Zeus (or Hades in some versions) and Kore-Persephone; while still an infant, he is installed by his father on the throne of the universe. Hera in her jealousy sends the Titans to kill the divine child. The Titans distract Zagreus with various “toys” (or “tokens of sacrament” as M.L. West thinks), including a mirror, and attack him. The infant god tries to escape by changing into different forms, and is finally caught in the shape of a bull and torn into seven parts. The Titans then boil the pieces in a cauldron, roast the divine flesh on spits and taste it.[13] Zeus finally takes notice of their outrageous actions and burns all the Titans with his thunderbolt; from their ashes mankind is born. Athena (or in some versions Rhea-Demeter) saves the heart of Zagreus and buries it in Delphi, or else Apollo himself buries the remains. From the heart the god will be reborn as Dionysus, the son of Semele (or, in some versions of the story, Rhea-Demeter reconstitutes him from the remains of the divine body).

The mythical dismemberment (sparagmos) of Dionysus-Zagreus (paralleled by the mythical sparagmos of Orpheus) is believed to be reflected in sacrificial rites,[14] as practiced across the Greek world in the secret (mystery) cult of Dionysos; these rites were particularly prominent in Thrace. The potential existence of oral Thracian ‘Orphic’ traditions, as a substrate in Greek literary Orphism, has long been the object of scholarly discussions; so far there appears to be no general consensus on any of this. The connections between Orpheus and Thrace are, at least, very well attested.[15] One especially evocative testimony is Plutarch’s comment that Macedonian and Thracian women from far-off antiquity were addicted to Orphic and Dionysian rites:

But concerning these matters there is another story to this effect: all the women of these parts were addicted to the Orphic rites and the orgies of Dionysus from very ancient times (being called Clodones and Mimallones), and imitated in many ways the practices of the Edonian women and the Thracian women about Mount Haemus, from whom, as it would seem, the word threskeuein came to be applied to the celebration of extravagant and superstitious ceremonies.” (Plutarch, Alexander 2.5; trans. B. Perrin; the Greek text is available here).

Was the Thracian identity of Rhodopis connected with her choice to offer iron spits for ox sacrifice in Apollo’s sanctuary at Delphi? Maybe not; we don’t have explicit or incontrovertible evidence, but the question is a legitimate one to pose and contemplate.

We end our tale about Rhodopis without the certainty of having solved all the pieces of this absorbing puzzle. And yet, Herodotus remains not only a superb storyteller but also an unrivaled educator who never fails to awake the imagination and inspire the curiosity of his audience to learn more, to inquire and investigate further.

Dobrinka Chiekova teaches Ancient History at The College of New Jersey. Her research focuses on various aspects of the history and epigraphy of the Greek city-states on the ancient Black Sea. Her monograph Cultes et vie religieuse des cités grecques du Pont Gauche explores the religious traditions and cultural interactions in the region. She has previously written for Antigone on Athenians’ forgive-and-forget attitude, the Mother Goddesses of Thrace, and the ancient borders of Classics.

Further Reading

Herodotus

The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories, trans. A.L. Purvis, edited by R.B. Strassler, introduction by R. Thomas (Anchor, New York, 2009).

Herodotus: The Histories, trans. T. Holland (Penguin, London, 2014).

D. Asheri, A. B. Lloyd, A. Corcella, O. Murray & A. Moreno, A Commentary on Herodotus Books I-IV (Oxford UP, 2007).

Sappho

A. Bierl & A. Lardinois (edd.), The Newest Sappho: P. Sapph. Obbink and P. GC Inv. 105, Frs. 1-4: Studies in Archaic and Classical Greek Song, Vol. 2 (E.J. Brill, Leiden, 2016).

J.B. Lidov, “Sappho, Herodotus and the ‘Hetaira'”, Classical Philology 97 (2002) 203–37.

D. Rayor (trans.), A. Lardinois (ed.), Sappho. A New Translation of the Complete Works, (Cambridge UP, 2023).

Orpheus and orphism

A. Barnabé, Poetae Epici Graeci. Testimonia et Fragmenta. Pars II: Orphicorum et Orphicis Similium Testimonia et Fragmenta. Fasc. 1-2 (Munich: Teubner, 2004–5).

A. Barnabé, “Autour du mythe orphique sur Dionysos et les Titans. Quelques notes critiques”, in D. Acorinti & P. Chuvin (edd.), Des géants à Dionysos. Mélanges F. Vian (Edizioni dell’Orso, Alessandria, 2003).

W. Burkert. Greek Religion (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 1985).

R. Edmonds, “Tearing apart the Zagreus myth: a few disparaging remarks on Orphism and Original Sin”, Classical Antiquity 18.1 (1999), 3573.

R. Edmonds, Redefining Ancient Orphism: A Study in Greek Religion (Cambridge UP, 2013)

A. Fol, Der thrakische Dionysos I: Zagreus (St. Kliment Ochridski, Sofia, 1993).

F. Graf, Oxford Classical Dictionary, s.v. Orphism

A. Henrichs, “Dionysos dismembered and restored to life: the earliest evidence (OF 50” I–II), in M. Herrero de Jáuregui et al. (edd.).,Tracing Orpheus: Studies of Orphic Fragments, (De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, 2012) 61–68.

O. Kern (ed.), Orphicorum Fragmenta (Weidmann, Berlin, 1922).

M.L. West, The Orphic Poems (Oxford UP, 1983).

Notes

| ⇧1 | Diodorus 1.64.14, probably paraphrasing from the 3rd-century-BC Greco-Egyptian historian Hecataeus of Abdera (FGrH 264 F 25): “And this last pyramid, some say, is the tomb of the courtesan Rhodopis, for some of the nomarchs became her lovers, as the account goes, and out of their passion for her carried the building through to completion as a joint undertaking.” (trans. C.H. Oldfather; for the Greek text, see here; Pliny, Natural History 36.17: “Such are the marvellous Pyramids; but the crowning marvel of all is, that the smallest, but most admired of them – that we may feel no surprise at the opulence of the kings – was built by Rhodopis, a courtesan! This woman was once the fellow-slave of Aesop the philosopher and fabulist, and the sharer of his bed; but what is much more surprising is that a courtesan should have been enabled, by her vocation, to amass such enormous wealth.” For the Latin text, see here. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Strabo, Geography 17.1.33: “Farther on, at a greater height of the mountain, is the third pyramid, which is much less than the two others, but constructed at much greater expense; for from the foundation nearly as far as the middle, it is built of black stone. Mortars are made of this stone, which is brought from a great distance; for it comes from the mountains of Ethiopia, and being hard and difficult to be worked, the labour is attended with great expense. It is said to be the tomb of a courtesan, built by her lovers, and whose name, according to Sappho the poetess, was Doricha. She was the mistress of her brother Charaxus, who traded to the port of Naucratis with wine of Lesbos. Others call her Rhodopis. A story is told of her, that, when she was bathing, an eagle snatched one of her sandals from the hands of her female attendant and carried it to Memphis; the eagle soaring over the head of the king, who was administering justice at the time, let the sandal fall into his lap. The king, struck with the shape of the sandal, and the singularity of the accident, sent over the country to discover the woman to whom it belonged. She was found in the city of Naucratis, and brought to the king, who made her his wife. At her death she was honoured with the above-mentioned tomb.” (trans. H.C. Hamilton; for the Greek text, see here. |

| ⇧3 | G. Donelli, “Herodotus, the Old Sappho and the Newest Sappho,” Lexis 39.1 (2021) 14–34. |

| ⇧4 | “When you die you’ll lie dead. No memory of you, / no desire will survive, since you’ve have no share / in the Pierian roses. / But once flown away / you’ll wander among the obscure dead, / invisible even in the house of Hades.” (Fr. 55; trans. D. Rayor). |

| ⇧5 | The scholarly debate surrounding Ovid’s authorship of Sappho’s letter (Epistula Sapphus) doesn’t affect the argument since this ancient text undoubtedly reflects a Classical tradition. |

| ⇧6 | See n.2 above and the Greek text here. |

| ⇧7 | Deipnosophistae 13.69: “and it was Rhodopis who dedicated those celebrated spits at Delphi, which Cratinus mentions in the following lines…” (trans. C.D. Yonge; for the Greek text, see here. |

| ⇧8 | De Pythiae oraculis 14: “When we had passed the house of the Acanthians and Brasidas, the guide pointed out to us the site where iron spits of Rhodopis the courtesan were once placed” (trans. F.C. Babbitt; for the Greek text, see here. |

| ⇧9 | L.H. Jeffery, The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece (Oxford UP, 1961) 102; E. Mastrocostas proposes an even more elaborate restoration: [Τοὺς ὀβελοὺς ἀνέθε]κε Ῥοδ[ο͂πις τἀπόλλονι] [δεκάταν] or [Το͂ι Ἀπόλλονι ἀνέθε]κε Ῥοδ[ο͂πις δεκάταν]. “Rhod[opis dedicat]ed [the spits to Apollo a tenth of her fortune]” (Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 13.364). |

| ⇧10 | Ibid., 124: “She wished to make a memorable gift; may it not have been the size and quantity which made it so?” ; A. Lloyd, Commentary ad Herodotus 2.135. |

| ⇧11 | L. Kurke, Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold. The Politics of Meaning in Archaic Greece (Princeton UP, NJ, 1999) 223–4 and note 4 with bibliography. |

| ⇧12 | Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) 7.1, 85-87, #27–8, 32–5, 37–8, 45, 49, 55. |

| ⇧13 | For these details, see Clement of Alexandria, Exhortations to the Greeks, 2.9: “And it is worthwhile to quote the worthless symbols of this rite of yours in order to excite condemnation: the knuckle-bone, the ball, the spinning-top, apples, wheel, mirror, fleece! Now Athena made off with the heart of Dionysus, and received the name Pallas from its palpitating (pallein). But the Titans, they who tore him to pieces, placed a caldron upon a tripod, and casting the limbs of Dionysus into it first boiled them down; then, piercing them with spits, they “held them over Hephaestus [i.e. fire].” Later on Zeus appeared; perhaps, since he was a god, because he smelt the steam of the flesh that was cooking, which your gods admit they “receive as their portion.” He plagues the Titans with thunder and entrusts the limbs of Dionysus to his son Apollo for burial. In obedience to Zeus, Apollo carries the mutilated corpse to Parnassus and lays it to rest.” (trans. G. W. Butterworth). |

| ⇧14 | See for example A. Henrichs, “Greek Maenadism from Olympias to Messalina,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 82 (1978) 121–60; cf. also the idea of S. Reinach, Orpheus. Histoire générale des religions (Paris, 1930) 26–7, about the intimate connection between the idea of theophagy and animal sacrifice. |

| ⇧15 | See for example Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae VII 1 s.v. Orpheus IV; A. Barnabé, Poetae Epici Graeci. Testimonia et Fragmenta: Orphicorum et Orphicis Similium Testimonia et Fragmenta. Pars II, Fasc. 2 (De Gruyter, Munich/Leipzig, 2005) 99–101; and the excellent article by V.J. Liapis, “Zeus, Rhesus, and the Mysteries,” Classical Quarterly 57 (2007) 381–411. |