Danuta Shanzer

“But to express compassion for those distant fellow humans would be, I suspect, an act of mere rhetoric. Our power to pollute and destroy the present, the past, and the future is incomparably greater than our feeble moral imagination.”[1]

Other peoples’ minds and psyches are notoriously impenetrable to us. But the gap can in some cases be bridged by questionable phenomena such as mind-reading or telepathy,[2] or by empathy.

Sympathy is different, viz it is an emotional act, namely of commiseration with another’s plight. It can be painful for the one who expresses it, but assuaging for the one who is sympathized with. It brings with it an (often ritualized) assurance of support, or at the very least of common humanity. Sympathy often takes a discursive form: “I am sorry for your loss.”

Empathy is trickier. The concept requires some cunning searching in ancient sources, for it isn’t captured by facile lexemes. There is something that looks like it: Greek ἐμπάθεια (empatheia) – but it isn’t what we call empathy. In its current sense that word first entered the English lexicon in 1909 as a translation of the German Einfühlung. Empathy isn’t an emotion, but an emotional ability: ‘empaths’ can read frequencies that others can’t. They can also pick up on non-verbal cues. Simon Baron-Cohen, confronting the problem of evil, has argued that empathy can be quantitatively captured by neuroscientists. Empathy is usually evoked in contexts involving pity and sympathy, not rejoicing. I would argue for a stronger definition that included darker insights about Imagined Others’ feelings and intellectual or religious convictions.

What Aristotle says about pity in his Rhetoric remains both relevant and interesting: that the evil was undeserved was a precondition for pity.[3] He noted that we feel more of it for those like us and less for those who are farther away from us, and that it is easier to pity our contemporaries than the denizens of a distant past.[4] But reenactments and relics can still trigger pity.[5]

Empathy can help one to make more universal moral decisions in order to spare distant unknowns who could be imperiled by the Mandarin Paradox.[6] Orson Welles’ Harry Lime offered the amoral, and ultimately unempathetic, diabolical temptation case from the height of the ‘Wiener Riesenrad’ (the famous Ferris wheel at the entrance of the Prater amusement park in Vienna) in Carol Reed’s 1949 film The Third Man:

“Would you really feel any pity, if one of those dots stopped moving forever? If I offered you 20,000 pounds for every dot that stopped, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money? Or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spend? Free of income tax, old man…”

Remember when all we knew of was what we had seen or heard directly, or heard of, or read of, and when we weren’t inundated with emotional fodder for empathy and pity, horror, or outrage? Technology changed that: first radio, then television (still limited), but now the internet is ubiquitous – and addictive. Local Germans were forced by the Allies to view the liberated concentration camps. As punishment of course, but above all because autopsy is a remedy against denial and conspiracy theories. They would then have to acknowledge the reality of the Holocaust. Contrast our times: now, as we can see after the events of 7 October 2023, the pornography of violence is instrumentalized from all sides, while also being faked. Our online hell is simultaneously a hall of mirrors.

But one can also imagine how excessive empathy could lead to a sort of emotional burnout.[7] The Sound Machine, a short story by Roald Dahl, explores the sanity of an inventor whose amplifier enables him to hear the screams of roses being pruned or trees being axed. As a philologist and literary scholar, I believe in the power of words to move and convince, perhaps even sometimes to transcend hatreds, and heal. And this involves different levels of empathy to try to overcome my twin obstacles (long ago and far away) as well as, perhaps contradictorily, to be aware that the past is a foreign country.

Yet intellectual empathy is also seen as a handmaid of history. R.G. Collingwood and John Lewis Gaddis both felt the intellectual process of putting oneself in another’s shoes to be essential for writing it.[8] The great Roman historian Tacitus imagined the enemy (Calgacus, a Caledonian chieftain) saying of the invading Romans: “They create a desolation and call it peace.”[9] He also entered the head of the besieged Roman emperor Vitellius as he was trying to hide while everything collapsed around him: he was terrified, but pulled himself together to face his executioners with reproachful dignity.[10]

Neither Collingwood nor Gaddis, however, thought of empathy in its modern “touchy feely” sense. Christopher Browning, who wrote the history of the Final Solution from a very special German archive,[11] noted that one must attempt to empathize in order to understand, but that understanding is not excusing.

“Another possible objection to this kind of study concerns the degrees of empathy for the perpetrators that is inherent in trying to understand them. Clearly the writing of such a history requires the rejection of demonization. The policemen in the battalion who carried out the massacres and deportations, like the much smaller number who refused or evaded, were human beings. I must recognize that in the same situation, I could have been either a killer or an evader — both were human — if I want to understand and explain the behavior of both as best I can. This recognition does indeed mean an attempt to empathize. What I do not accept, however, are the old clichés that to explain is to excuse, to understand to forgive. Explaining is not excusing; understanding is not forgiving. Not trying to understand the perpetrators in human terms would make impossible, not only this study, but any study of Holocaust perpetrators that sought to go beyond one-dimensional caricature.”[12]

In 2011, Simon Baron-Cohen echoed this sentiment as part of his discussion of the rehabilitation of murderers:

“My own view is that we should do this – no matter how bad their crime. It is the only way we can establish that we are showing empathy to the perpetrator, not just repeating the crime of turning the perpetrator into an object and thus dehumanizing them. To do that renders us no better than the person we punish.” He saw empathy as “a universal solvent”.[13]

So far I have tried to outline some modern approaches to the role of empathy in navigating the straits between absolutism and complicity. These questions have obvious relevance to matters judicial, but also to moral philosophy, psychology, and the writing of history. Now we turn to the ancient world, for I will concentrate on a single historical episode and some of the ancient voices that responded to it.

The Year 410 and its Aftermath

On 24 August 410, a Visigothic army under Alaric I entered Rome and sacked the city. This event has had an enormous historical resonance ever since. Reinhart Herzog said: “We are living in late antiquity.”[14] The inhabitants of the city would at the time have been primarily Christian. Alaric and his troops would likewise have been Christians, but Arians, not Nicenes like most of the inhabitants of Rome. So the event automatically had religious political overtones.

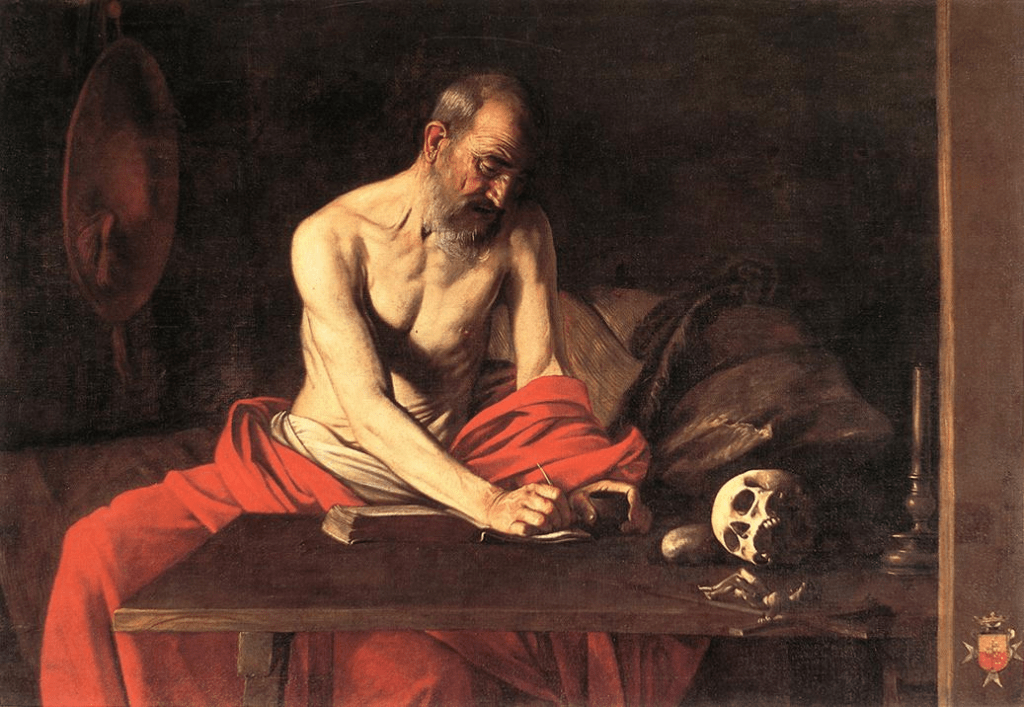

Jerome (c.345–420), when in Bethlehem eventually heard the news and wrote back (in 412) to a female friend, Principia, who had suffered along with her elder friend Marcella during the Sack of Rome. Let’s think ourselves into the past and listen to Jerome in his letter 127.12. He began in his own words, and imagined his own voice faltering even as he dictated the letter and being interrupted by sobbing. He wrote with sympathy and with horror:

While these things were taking place in Jebus, a dreadful rumor reached us from the West. We heard that Rome was besieged, that the citizens were buying their safety with gold, and that when they had been thus despoiled they were again beleaguered, so as to lose not only their substance but their lives. The speaker’s voice failed, and sobs interrupt his utterance. The city which had taken the whole world was itself taken; nay, it fell by famine before it fell by the sword, and there were but a few found to be made prisoners. The rage of hunger had recourse to impious food; men tore one another’s limbs, and the mother did not spare the baby at her breast, taking again within her body that which her body had just brought forth. (Trans. F.A. Wright, Loeb Classical Library)

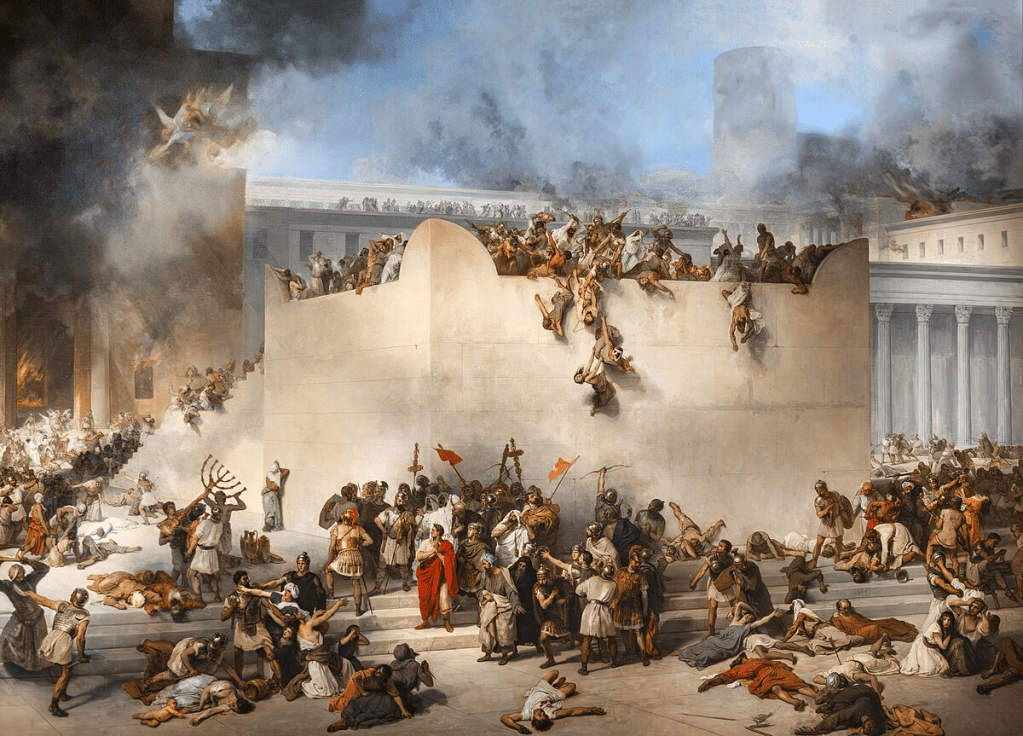

Siege, demands for ransom, then siege again. Mighty Rome was taken, but fell first to starvation, for its inhabitants had recourse to cannibalism.[15] A mother ate her own child. Awareness of intertextuality helps us hear Jerome’s letter properly. He evoked the famous curses from Deuteronomy 28:57, where an elegant mother is reduced to eating her own afterbirth. And also, I would argue, the story of Maria, the starving Jewish mother who in desperation ate half of her child, during the Siege of Jerusalem in AD 70, and offered the rest as a Thyestean feast to the Jewish rebels.[16] Her tragic act eventually backfired and decreased sympathy for the Jews: Josephus tells us that Titus used it as an excuse for destroying the city.[17]

At the end of Ep. 127.12 comes a group of quotations, all related to the sacking of cities: a very short one from Isaiah 15:1, one from Psalm 78:1–3. and one from Vergil’s Aeneid Book 2:

Nocte Moab capta est, nocte cecidit murus eius.[18]

“In the night was Moab taken, in the night did her wall fall down.”

Deus, venerunt gentes in hereditatem tuam, polluerunt templum sanctum tuum, posuerunt Hierusalem in pomorum custodiam, posuerunt cadavera servorum tuorum escas volatilibus caeli, carnes sanctorum tuorum bestiis terrae. effuderunt sanguinem ipsorum sicut aquam in circuitu Hierusalem et non erat, qui sepeliret.[19]

“O God, the heathen have come into thine inheritance; thy holy temple have they defiled; they have made Jerusalem an orchard. The dead bodies of thy servants have they given to be meat unto the fowls of the heaven, the flesh of thy saints unto the beasts of the earth. Their blood have they shed like water round about Jerusalem; and there was none to bury them.”

Quis cladem illius noctis, quis funera fando

explicet aut possit lacrimis aequare dolorem?

urbs antiqua ruit multos dominata per annos

plurima perque vias sparguntur inertia passim

corpora perque domos, et plurima mortis imago.[20]

“Who can tell that night of havoc, who can shed enough of tears | For those deaths? The ancient city that for many a hundred years | Ruled the world comes down in ruin: corpses lie in every street. | And men’s eyes in every household death in countless phases meet.” (Trans. F.A. Wright, Loeb Classical Library)

Jerome achieves a magnificent emotional effect by combining these different voices, sounding together: Old Testament and pagan. One of his primary empathic techniques is to connect this sack with other comparable ancient events, including an attack on Jerusalem and the Fall of Troy. Old Testament times, pagan mythological time, and now (alas!) Christian times. We have seen how Jerome lets the overtones of previous sieges ring through as in polyphony. The highest pathetic rhetoric, but also a beautiful expression of empathic universalism.

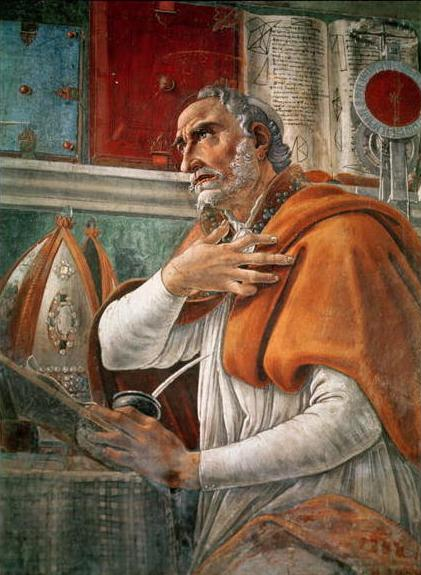

Many famous authors reacted to the Sack of Rome.[21] One of them makes a particularly interesting case study, namely Augustine of Hippo (354–430). He was that rare Church Father whose sentimental and sexual history is (in part) known to us. And even though he was a man of the finest feelings, he had severe reservations about emotional responses to literature. In Confessions 1.13.20–1 he harshly criticized his youthful self for weeping over Queen Dido, who had committed suicide for love in Vergil’s Aeneid 4, while he himself was committing emotional suicide by not loving God:

This was better than the poetry I was later forced to learn about the wanderings of some legendary fellow named Aeneas (forgetful of my own wanderings) and to weep over the death of a Dido who took her own life from love. In reading this, O God my life, I myself was meanwhile dying by my alienation from you, and my miserable condition in that respect brought no tear to my eyes. What is more pitiable than a wretch without pity for himself who weeps over the death of Dido dying for love of Aeneas, but now weeping over himself dying for his lack of love for you, my God, light of my heart, bread of the inner mouth of my soul, the power which begets life in my mind and in the innermost recesses of my thinking. (Trans. H. Chadwick, Oxford World Classics).

It is worth noting that when replying to a sensitive question about the appropriate care for the bodies of the dead, he was (on the whole) unsentimental about the question of Christian burial: burials were about the living and who they are, not about the dead. [22] I will return to the dead shortly.

Augustine was Bishop of Hippo in Africa during and after the Sack of Rome, and had to comfort and console Roman refugees as well as respond to pagans who thought that neglect of the pagan gods and violation of the pax deorum (peace of the gods) had brought about the disaster. Alaric was seen as a scourge of the gods. The City of God was ultimately the venue for Augustine’s response. To his congregation he argued that the event wasn’t that bad (it could have been worse), that Rome survived, and that worse had happened before.[23] All consolatory. But later in the City of God, he would argue against the pagans that human might had defended Rome, not the pagan gods, and Rome wasn’t such a great thing anyway. And whom did God allow to capture Rome? Augustine kept strategically silent about Alaric’s religion.

The Spanish priest Orosius, to whom Augustine passed the baton, engaged in shameless special pleading. The Lord had not allowed Rome to be taken by the pagan Radagaisus in 406, but by Alaric, “who was Christian and closer to a Roman.”[24] Did that make victims of the siege feel better?

We have disinformation and questionable news today. The same was true in antiquity. For as soon as the Christians saw the Sack of Rome as a theological and political rather than a military problem, the interactions between Visigoths and Christian Romans took on a new importance. It began to be apologetically necessary to show that being Christian counted for something when all about you were losing their heads and blaming it on you.[25]

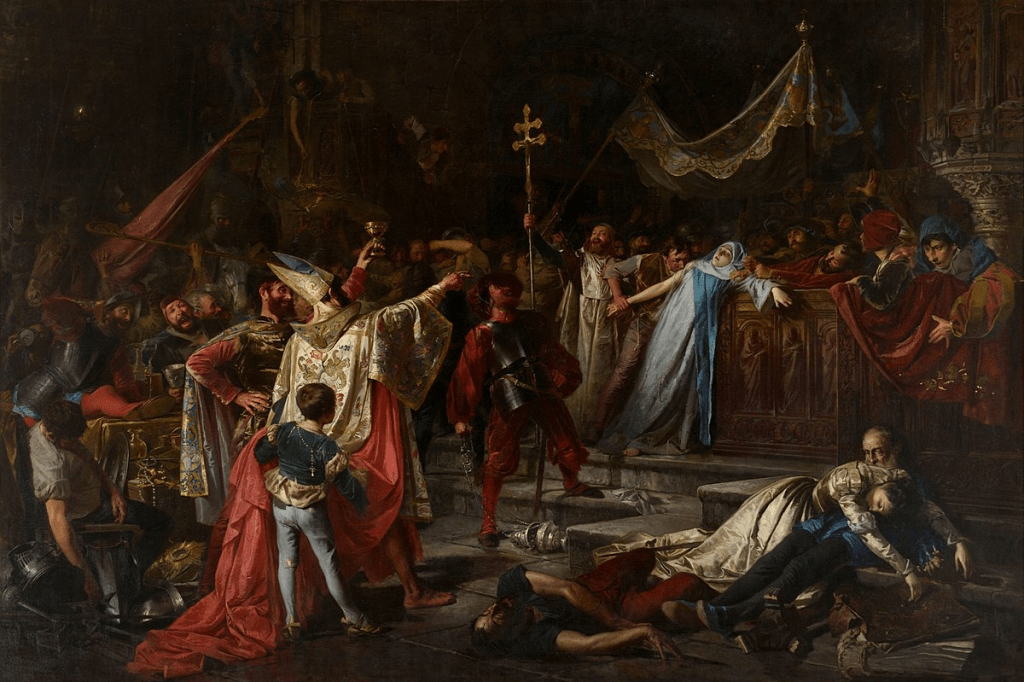

The historiography of the Sack of Rome includes precisely such a narrative attested in different forms in different authors – the tale of the merciful barbarians.[26] This appears in Orosius’ Historiae 7.39.3–10 as an account of how an elderly nun begged a Christian Goth to respect the treasure of Saint Peter, how Alaric agreed, and how Romans and treasure were conducted safely to sanctuary in a communal love feast of victors and vanquished. Jerome’s Epistle 127.13 has his own version with a different focus.

A blood-stained victorious Goth entered his heroine Marcella’s house, seeking plunder. The women had none, but Marcella, when being beaten, begged him not to violate her younger friend Principia. A miracle occurred: Christus dura corda mollivit et inter cruentos gladios invenit locum pietas. The invader unexpectedly changed scripts: he didn’t murder or rape, but led the two women to sanctuary in the basilica of Saint Paul. Another edifying story from the Sack of Rome, highlighting his heroine’s courage!

There are various ways of reading these tales. One could believe them, especially Jerome’s, as examples of empathy and mercy in war. One could see edifying and heart-warming tales implicitly pleading for mercy for religious women in war – “do’s” for invaders. Or one could read them as Christian propaganda, which is what I think they are.[27]

Many Christians must have posed the essential question of the theodicy: How could a just and merciful and omnipotent god let such things happen to just people in Christian times? And the question clearly came up in a context that Augustine found profoundly challenging, namely the fate of Christians during the sack. He had to respond to reports of atrocities and tragedies. Children, as we saw, were magnets for propagandists, but women were too. Now, I work on Augustine and, if I could spend time with anyone from antiquity, it would be with him. But in the case of the Sack of Rome his towering genius and human feeling succumbed to polemic and special pleading, and he produced an argument that makes many of us cringe. And it involves a significant failure of empathy.

In Rome, captured nuns had clearly been raped during the Sack. And, from Augustine’s response in the City of God 1.16–28, we know questions were raised both by pagans and Christians. Why, a pagan might ask, had they not committed suicide to protect their honor? Augustine’s polemical response to this was to compare the Roman heroine Lucretia who had committed suicide after telling her husband how she had been raped by Tarquin (c.509 BC). [28] She was the exemplum of Roman marital chastity, yet Augustine deconstructed her virtue.

Augustine argues that chastity resides in the soul. One could forgive those who commit suicide to avoid rape, but one isn’t in fact polluted by another’s lust. A soul is only subject to another’s lust if it consents to sin. In City of God 1.19 he suggested that Lucretia probably consented to Tarquin’s rape – hence her suicide. She had “wanted” it. The climax of all of this is an appalling argument in City of God 1.28 that, if a Christian virgin was raped and was suicidally distressed, she should ask herself whether she was being punished for excessive pride in her virginity. Or – and this was not Augustine’s finest hour – perhaps she was about to succumb to some other weakness, so that she was rescued by rape from, say, excessive pride in her chastity. She ‘had it coming’.

This is very far from the man who had wept for Dido’s suicide. What we see here is a failure to see all these women as human beings (homines), regardless of their historic contingencies. I would have liked Augustine the pastor to try to console Lucretia and not, because of his pagan opponents, tell her that she must have secretly wanted to be raped. Or not tell a raped nun that she had been about to be guilty of pride in her vocation and needed to be humbled by rape. He allowed himself to be swept up in polemic that drove him into lack of empathy for women, both pagan and Christian, secular virgins and nuns. “An intellectual hatred is the worst.” [29] His dogma had no empathy for their fate. In 446 Pope Leo would propose a demoted, intermediate status for nuns who had been raped: above celibate widows, but below virgin nuns.[30]

The Fall of Troy

Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt (Aeneid 1.462). I mentioned Augustine’s rationalist attitudes towards burial. These were driven by Christian doctrines about God’s omnipotence and the Resurrection of the Flesh. God could reconstitute even those who had been consumed in fire or eaten by fish. But pre-Christian pagans thought otherwise: burial was not just a consolation for the living; the souls of the unburied were denied access to the afterlife.

Diminishing affect caused by time and space does not apply to myth.[31] So, like Jerome, I’m going to turn to Troy and to a story of resolution, even if not reconciliation, effected by initial shuttle diplomacy, a face-to-face encounter, and shared humanity. I speak of the ransoming of Hector’s corpse from Achilles in Iliad 24.

Long ago Matthew Arnold spoke of “touchstones”. These were irrefutably great verses that set a standard for other works. One of the ones he cited (without comment) was Iliad 24.523: καὶ σὲ γέρον τὸ πρὶν μὲν ἀκούομεν ὄλβιον εἶναι, “I have heard that you too, old man, were blessed/fortunate in the past.”[32] Why is this a magnificent line? Achilles had addressed it to Priam of Troy who had come to supplicate him for his son Hector’s body. In “You too, old man,” Achilles found common humanity (homo sum…), and the two in their shared grief some fragile, but functional, reconciliation.[33]

In this book of the Iliad alone do the gods on both sides work together. The request for mercy goes in a chain from Apollo to Zeus to Iris to Thetis, and to Achilles, who immediately capitulates.[34] Zeus then motivates the other side, sending Iris to Priam. The messenger goddess doesn’t materialize in a full epiphany. We are told that she “spoke softly”:

στῆ δὲ παρὰ Πρίαμον Διὸς ἄγγελος, ἠδὲ προσηύδα

τυτθὸν φθεγξαμένη.[35]

One could imagine the goddess Iris here as in fact some sort of inspirational inner voice, not an unambivalent divine command. Priam sets out to be escorted by Hermes in human disguise as an (enemy) Myrmidon.[36] He learns from Hermes that Hector’s corpse is miraculously preserved through the gods’ good offices. The god’s play-acting refusal of a gift (Il. 24.433–5) establishes the possible bona fides of the enemy. And only in Achilles’ quarters does Hermes reveal his divinity (Il. 24.460–4) to Priam.

The King of Troy’s appeal is through fatherhood: he is the father of many, yet he has lost innumerable sons. Achilles has an aged father like himself (Il. 24.486ff.). The two mourn in parallel. Achilles remembers Peleus’ fortune (and ill-fortune) in his single ill-fated son. They are not arguing about statistics. And then comes the magic moment, when Achilles says that he is bringing sorrow on Priam in Troy, but isn’t caring for his own father:[37] “And you, old sir, we are told, you prospered once… but now the Uranian gods brought us, an affliction, upon you.”[38] He is finally able to break the cycle of revenge, return Hector’s corpse, and offer the old king guest-friendship (xeniā) and a bed for the night. Achilles will still die, Troy will still fall, but men will have behaved like human beings. This started when Zeus told Hera that Hector too had been beloved of the gods: ἀλλὰ καὶ Ἕκτωρ | φίλτατος ἔσκε θεοῖσι βροτῶν οἳ ἐν Ἰλίῳ εἰσίν.[39]

In Dryden’s “Alexander’s Feast”, the bard Timotheus moves Alexander to pity by reminding him of the fate of his enemy Darius of Persia: unburied, as were Alexander’s own soldiers.[40] Antiquity knew all about Fortune’s wheel. Those on top would do well to contemplate a sudden reversal.

These voices of division and justification from the Late Antique world show us how nothing changes. But our most ancient Classical text still has something to teach us about how courage, personal contact, and ordinary acts shared can help resolve a grim cycle of revenge. Augustine was a theologian and philosopher; Jerome primarily a philologist. And, as I hope to have shown, Jerome’s literary instincts, which allowed polyphony and empathy, were the right ones. The pagan, Jewish, and Christian voices all sang together. It was Augustine’s defensive ideology that led him into the ruthless and intrusive argumentation of City of God 1. I prefer the youth who could weep for the mythic Dido.[41]

Danuta Shanzer, a Classicist and Medievalist, is retired Professor of Late Antique and Medieval Latin Philology at the University of Vienna. She specializes in the Latin literature and social and religious history of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Favourite authors include Martianus Capella, Prudentius, Ausonius, Avitus of Vienne, Augustine, Jerome, Gregory of Tours, and Desiderius of Cahors. Her work explores heaven and hell, the philological and literary, and the historical and theological in the Later Roman Empire (AD c.200-500) and in many of the barbarian successor kingdoms.

Works Cited and Further Reading

Matthew Arnold, Essays on the Study of Poetry and a Guide to English Literature (Macmillan & Co., London/New York, 1904).

Simon Baron-Cohen, The Science of Evil: On Empathy and the Origins of Cruelty (Basic Books, London/New York, 2011).

Christopher R. Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (Harper Perennial, New York, 1993).

Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita (trans. M. Glenny. Signert, New York, 1967).

Gillian Clark, “Augustine and the merciful barbarians,” in R.W. Mathiesen & D. Shanzer (edd.), Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity (Ashgate, Farnham, Surrey /Burlington, VT. 2011) 33–42.

R.G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford UP, 1946).

Roald Dahl, “The Sound Machine,” The New Yorker, 9 Sep., 1949.

John Lewis Gaddis, The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past (Oxford UP, 2002).

Carlo Ginzburg, “Killing a Chinese Mandarin: the moral implications of distance,” Critical Inquiry 21.1 (1994) 46–60, available here.

Reinhart Herzog, Wir leben in der Spätantike: eine Zeiterfahrung und ihre Impulse für Forschung. Vol. 4: Thyssen-Vorträge: Auseinandersetzungen mit der Antike (C.C. Buchners, Bamberg, 1987).

Thomas Hodgkin, Italy and Her Invaders. Vol. I, Book I: The Visigothic

Invasion (Russell & Russell, New York, 1967).

C.W. Macleod, Homer Iliad Book XXIV (Cambridge UP, 1982).

Danuta Shanzer, “Avulsa a latere meo: Augustine’s Spare Rib – Augustine Confessions 6.15.25,” Journal of Roman Studies 92 (2002) 157–76.

Danuta Shanzer, “Augustine’s Anonyma I and Cornelius’ concubines: how philology and literary criticism can help in understanding Augustine on marital fidelity,” Augustinian Studies 48.1–2 (2017) 201–24.

Bryan Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (Oxford UP, 2005).

Notes

| ⇧1 | Ginzburg (1994), 60. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | For an interesting literary example, see Mikhail Bulgakov’s great novel The Master and Margarita (Bulgakov 1967, 26–7) where Jesus reads Pilate’s mind during his own interrogation, and thus knows of both his love for his dog and his crippling migraine. |

| ⇧3 | Rhetoric 2.8.1385b14 (tou anaxiou) and 1385b34 (epieikeis). |

| ⇧4 | Rhetoric 2.8 1386a25 and 1386a29. |

| ⇧5 | Rhetoric 2.8 1386a32ff.: visualizations that incorporate gestures, voice, costume, and mimicry make the psychological impact stronger; likewise the clothes of those who have suffered (relics avant la lettre). |

| ⇧6 | On which see Ginzburg (1994) 50–2 for Diderot, and 53–4 for Chateaubriand (misattributed by Balzac to Rousseau). Chateaubriand formulated it thus in his Génie du Christianisme (1802): “I put to myself this question: If you could, by merely wishing it, kill a fellow-creature in China, and inherit his fortune in Europe, with the supernatural conviction that the fact would never be known, would you consent to form such a wish?” |

| ⇧7 | Baron-Cohen (2011) 178–9 disagrees and concludes: “I remain skeptical because if an individual is overwhelmed to the point of not being able to separate their own emotions from someone else’s, in what sense can they be said to have super-empathy? In such a state of confusion they may simply be distressed rather than empathic.” He sees the possibility of making oneself sympathetically sick on other’s distress, but not of thereby being a genuine super-empath. |

| ⇧8 | Collingwood (1946) 39; Gaddis (2002) 124. |

| ⇧9 | Tacitus, Agricola 30: solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant. |

| ⇧10 | Tacitus, Histories 3.84.4. It is strange that Collingwood (1946) 39 claimed “Tacitus never tried to do this”. Perhaps he meant that Tacitus didn’t lay bare what he saw as his protagonists’ reasoning? |

| ⇧11 | Browning (1993) xiv-xvi: he used a public prosecutorial archive from Hamburg (1962–72) that contained transcriptions from interrogating 200 men. |

| ⇧12 | Browning (1993) xx. |

| ⇧13 | Baron-Cohen (2011) 175, 176. |

| ⇧14 | Herzog (1987). |

| ⇧15 | As Zosimus vividly puts it at Historia Nova 6.11, pretium impone carni humanae (the Latin phrase is cited within his Greek account). |

| ⇧16 | Bellum Judaicum 6.4.201–13; also retold in Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica 3.6.20–8. For Jerome’s knowledge of the HE, see De viris illustribus, prol.: Eusebius Pamphili in decem ecclesiasticae historiae libris maximo nobis adiumento fuerit. |

| ⇧17 | Bellum Judaicum 6.5.214: Titus refused to accept responsibility for the atrocity. |

| ⇧18 | This is not an exact quotation: the original (Isaiah 15:1–3) runs: quia nocte vastata est Ar Moab, conticuit; quia nocte vastatus est murus Moab, conticuit. ascendit domus, et Dibon ad excelsa, in planctum super Nabo; et super Medaba, Moab ululavit; in cunctis capitibus eius calvitium, et omnis barba radetur. In triviis eius accincti sunt sacco; super tecta eius et in plateis eius omnis ululatus descendit in fletum. |

| ⇧19 | The text in Jerome’s letter differs slightly from the Vulgate version of the Psalms. |

| ⇧20 | Vergil, Aeneid 2.361–5. |

| ⇧21 | These include Augustine, Jerome, Orosius, Rutilius Namatianus, Zosimus and Sozomen (see Shanzer 2002, Shanzer 2017). |

| ⇧22 | De cura pro mortuis gerenda 2.4. |

| ⇧23 | Sermo de excidio urbis. For summaries, see Clark (2011) 34. |

| ⇧24 | Orosius, Historiae 7.37.4 and 37.9. Augustine, City of God 5.23 discusses Radagaisus’ quasi-miraculous, near-bloodless defeat in what is virtually a pagan-Christian ordeal-by-battle. Stilicho might have viewed matters differently. |

| ⇧25 | With apologies to Rudyard Kipling, “If”. |

| ⇧26 | Discussed by Clark (2011). |

| ⇧27 | For yet another variant, see Sozomen 9.10 for heroic Roman matron and the Gothic soldier. She preferred death to dishonor. He tried to kill her, couldn’t, and relented. |

| ⇧28 | Livy, Ab Vrbe condita, 1.57–8. |

| ⇧29 | W.B. Yeats, “A Prayer for my Daughter.” |

| ⇧30 | Ward-Perkins (2005) 13, discussing Leo, Epp. 12.8 and 11. |

| ⇧31 | Ginzburg (1994) 48. |

| ⇧32 | Arnold (1904) 24–7. |

| ⇧33 | I say “fragile” because of the moment where Achilles shows his teeth again at Il. 24.560. There are limits to compliance, but rationality dictates subjection to the force majeure of a god. At Il. 24.583–5 Achilles worries that Priam’s grief might morph into anger. |

| ⇧34 | Il. 24.39. |

| ⇧35 | Il. 24.169–70. |

| ⇧36 | Il. 24.374: Μυρμιδόνων δ’ ἔξειμι, πατὴρ δέ μοί ἐστι Πολύκτωρ. |

| ⇧37 | Il. 24.540–2 οὐδέ νυ τόν γε | γηράσκοντα κομίζω, ἐπεὶ μάλα τηλόθι πάτρης | ἧμαι ἐνὶ Τροίῃ, σέ τε κήδων ἠδὲ σὰ τέκνα. |

| ⇧38 | Trans. R. Lattimore, The Iliad of Homer (Univ. of Chicago Press, IL, 1967; Il. 24.546–8 τῶν σε γέρον πλούτῳ τε καὶ υἱάσι φασὶ κεκάσθαι. | αὐτὰρ ἐπεί τοι πῆμα τόδ’ ἤγαγον Οὐρανίωνες | αἰεί τοι περὶ ἄστυ μάχαι τ’ ἀνδροκτασίαι τε. |

| ⇧39 | Il. 24.66–7. |

| ⇧40 | John Dryden, “Alexander’s Feast or the Power of Music” (1697), sections 4 (Darius) and 6 (The Grecian dead). The poem is an ode for Saint Cecilia’s Day, and was magnificently set by Handel in 1736. |

| ⇧41 | A German version of this paper was written for and delivered at the 17th Maimonides Lectures of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, “Empathie: eine multidisziplinäre Perspektive”, on 8 November 2023. On that occasion I noted that the Iliad may show how it is perhaps easier for multiple gods in a polytheistic system to reach agreement on human affairs than for the One Gods of the Abrahamic monotheisms. My warm thanks to Patrizia Giampieri-Deutsch and Hans-Dieter Klein for inviting me to participate in the Maimonides Symposion, to the members of my online Privatissimum for being such a good audience, to Ben Garstad and Ebrahim Afsah for many conversations about historiography, and to Mateusz Stróżyński for his generous editorial help. |