Mateusz Stróżyński

The aria Et incarnatus est from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s (1756–91) unfinished masterpiece Great Mass in C Minor (1783) is based on the Latin text of the Credo (literally “I believe”), which is known in English as ‘The Creed’, following the Church’s ancient Nicene Creed (as modified in AD 381). The Credo is part of the ‘Ordinary’ of the Catholic Mass (one of the texts that are part of every Mass), and is also central to the missa as a genre of Western sacred music developed in the Middle Ages. The Latin in-carnatio is a rendering of the Greek term ἐνσάρκωσις (ensarkōsis), which in turn refers to the famous verse from the Prologue to the Gospel of John: καὶ ὁ λόγος σάρξ ἐγένετο (John 1:14), “the Logos [often rendered “Word”] was made flesh”. Obviously, this part of the Latin Creed, just as this verse of the Fourth Gospel, refers to the Feast of the Nativity of the Lord, celebrated by Christian churches on 25 December, a couple of days after the Winter Solstice, the shortest day of the year.

At first, Christians tended to place the birth of Jesus in the spring (for example, around the Jewish Passover). However, it was never intended to be a precise date, but rather a symbol pointing towards the theological meaning of the event. It is believed that Christmas was first celebrated in 328, at the dedication of the basilica that was founded above the Grotto of the Nativity in Bethlehem, in the presence of the mother of Constantine the Great (272–337), the Holy Empress Helena (246/248–330). In Palestine, this holiday was celebrated under the name of Epiphany, on 6 January.

Epiphany collectively commemorated a series of events: Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi, the Baptism of Christ, and the Miracle at Cana. All of those were seen as instances of God revealing Himself to the world – whence the name of the feast (Epiphany means “revelation”). This tradition could be found not only in Palestine, but also in Egypt and eastern Syria; it still survives to this day in Armenia. The date of 6 January also had a symbolic meaning because it referred to the six days of creation in the Book of Genesis, and was commonly held to signify perfection and thus the entirety of God’s creation.

The actual feast of Christmas as the Lord’s Nativity originated in Rome, probably around the year 330. The 25th day of December was not chosen, as is commonly believed, under the influence of the Pagan festival of the Sol Invictus (“Invincible Sun”), but, again, because of the symbolic meaning of the winter solstice, when a “new sun” is born. Jesus Christ is referred to as the sun several times in the Bible. For instance, the prophet Malachi announces the coming of the Messiah, saying that “the Sun of righteousness shall rise” (Mal 4:2) and Zechariah, the father of St John the Baptist, in the famous hymn Benedictus (Luke 1:68–79), proclaims that “the dayspring from on high hath visited us” (Luke 1:78), referring to the incarnation of Christ in the womb of St Mary.

One of the so-called “Great O Antiphons” for the seven days preceding Christmas, “O Oriens” (sung on 21 December) refers to this imagery: O Oriens, splendor lucis aeternae, et sol justitiae: veni, et illumina sedentes in tenebris et umbra mortis (“O dawn of the east, brightness of light eternal, and sun of justice: come, and enlighten those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death”).

This in turn was popularized in the Advent hymn Veni, veni Emmanuel, whose third stanza in the English 1906 translation of T.A. Lacey runs:

O come, O come, thou Dayspring bright!

Pour on our souls thy healing light;

Dispel the long night’s lingering gloom,

And pierce the shadows of the tomb.

Rejoice! Rejoice! Emmanuel

Shall come to thee, O Israel.

This Biblical imagery was enough for ancient Christians to recognise their Lord as the true Sun, of which the physical sun is only a symbol, and to associate the Winter Solstice – the birth of the new sun, and the point from which the day begins to lengthen as the darkness recedes – with the birth of the Word Incarnate. St Augustine uses this beautiful symbolism of the Light increasing day by day after Christmas in several of his Nativity sermons (for instance, Sermo 186, chapter 3).

That symbolic dimension of Christmas was not, however, much to the taste of Father Edmund Hill OP, the English translator of the sermons, and a long-standing member of the Priory of St Michael Archangel in Cambridge. Hill called Augustine’s association of the Nativity with the winter solstice “a rather labored conceit”.[1] His argument is hopelessly irrelevant: Hill points out that it is only “in the northern hemisphere” and “temperate climes” that Augustine’s imagery really works, while – he seems to suggest – the inhabitants of “the tropics and the southern hemisphere” may have some problems with it. Yes, there are places where people celebrate Christmas at the height of the summer heat, but Jesus Christ was, nonetheless, born in a particular place and particular time, whether it fits the fashionable decolonisation narrative or not.

However, Mozart’s Et incarnatus est, one of the most sublime musical renderings of the Nativity, has nothing to do with the winter solstice of “the northern hemisphere” and “temperate climes”. On the contrary, it invokes, by musical means, a sense of the advent of the spring; it appears to be almost naïve and child-like, for instance, when we hear the flute, oboe, and bassoon sounding like three birds singing on a still-crisp April morning.

But we’re not allowed to stay in this naïve mood for very long, because the spring gradually reveals to us its profound symbolism. In C.S. Lewis’ words, the spring is

Of wrath ended

Of woes mended, of winter passed,

And guilt forgiven, and good fortune. (The Planets)

Yet the imagery of the spring hidden “in the bleak midwinter” brings to mind yet another curious intersection of Christmas symbolism and ancient Greco-Roman culture, namely, Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue:

ultima Cumaei venit iam carminis aetas;

magnus ab integro saeclorum nascitur ordo:

iam redit et Virgo, redeunt Saturnia regna;

iam nova progenies caelo demittitur alto.

tu modo nascenti puero, quo ferrea primum

desinet ac toto surget gens aurea mundo,

casta fave Lucina: tuus iam regnat Apollo. (Ecl. 4.4–10)

Now the last age by Cumae’s Sibyl sung

has come and gone, and the majestic roll

of circling centuries begins anew:

justice returns, returns old Saturn’s reign,

with a new breed of men sent down from heaven.

Only do thou, at the boy’s birth in whom

the iron shall cease, the golden race arise,

befriend him, chaste Lucina; ’tis thine own

apollo reigns. (trans. G.B. Greenough)

Virgil’s prophetic vision of the advent of a new Golden Age, of the new Sun, under the auspices of the luminous deities of Lucina and Apollo, of a child (puer) born of a virgin (virgo), moved some ancient Christians to believe that the Roman poet was inspired by the Holy Spirit to foretell by three or four decades the birth of Christ. Although St Jerome was a famous enemy of this interpretation, it flourished in the Middle Ages: Dante’s reverence for Virgil is perhaps the best-known testimony to the widespread belief that the Roman bard was the prophet of the Nativity. We can almost hear it in the Gregorian introit for Christmas Day:

Puer natus est nobis,

Et filius datus est nobis:

Cuius imperium super humerum eius:

Et vocabitur nomen eius, magni consilii angelus.

A child is born to us,

and a Son is given to us:

Whose government is upon His shoulder:

and His Name shall be called, the Angel of Great Counsel.

What is curious, however, in the imagery of the birth of the divine boy in the Fourth Eclogue is that it invokes the perfect springtime by marking the birth of the new life after the dark death of the winter. I have no idea whether Mozart read Virgil, but his Et incarnatus est seems like a perfect musical setting of that Golden Age atmosphere that the Fourth Eclogue brings into the archetypal event of the rediens Virgo and nascens puer:

at tibi prima, puer, nullo munuscula cultu

errantis hederas passim cum baccare tellus

mixtaque ridenti colocasia fundet acantho.

ipsae lacte domum referent distenta capellae

ubera, nec magnos metuent armenta leones;

ipsa tibi blandos fundent cunabula flores,

occidet et serpens, et fallax herba veneni

occidet, Assyrium volgo nascetur amomum. (Ecl. 4.18-25)

For thee, O boy,

first shall the earth, untilled, pour freely forth

her childish gifts, the gadding ivy-spray

with foxglove and Egyptian bean-flower mixed,

and laughing-eyed acanthus. Of themselves,

untended, will the she-goats then bring home

their udders swollen with milk, while flocks afield

shall of the monstrous lion have no fear.

Thy very cradle shall pour forth for thee

caressing flowers. The serpent too shall die,

die shall the treacherous poison-plant, and far

and wide Assyrian spices spring.

Shortly before writing the Great Mass in C Minor, Mozart closely studied the works of Bach and Handel, inspired by an Austrian diplomat and great enthusiast of music, Baron Gottfried von Swieten (1733–1803). Mozart’s music wasn’t only in dialogue with the Christian and Classical cultural tradition in general, but also with the musical traditions of Europe. And it’s worth remembering that in Mozart’s time it was very unusual to study the music of the past. Throughout the centuries, most people, have been primarily interested in contemporary music. Our own preoccupation with “classical music” and the fact that music that we usually hear around us consists not of symphonic or operatic works composed in our time, but mechanistic, endless stream of fast-food like pop-music, is another strange feature of the modern West. The great Austrian conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929–2016), who was one of the main figures in the revival of early music in the 20th century, suggested that this is because in each cultural period contemporary music shows people how they see reality and who they are. Our reality is, apparently, too ugly and boring for us to stand.

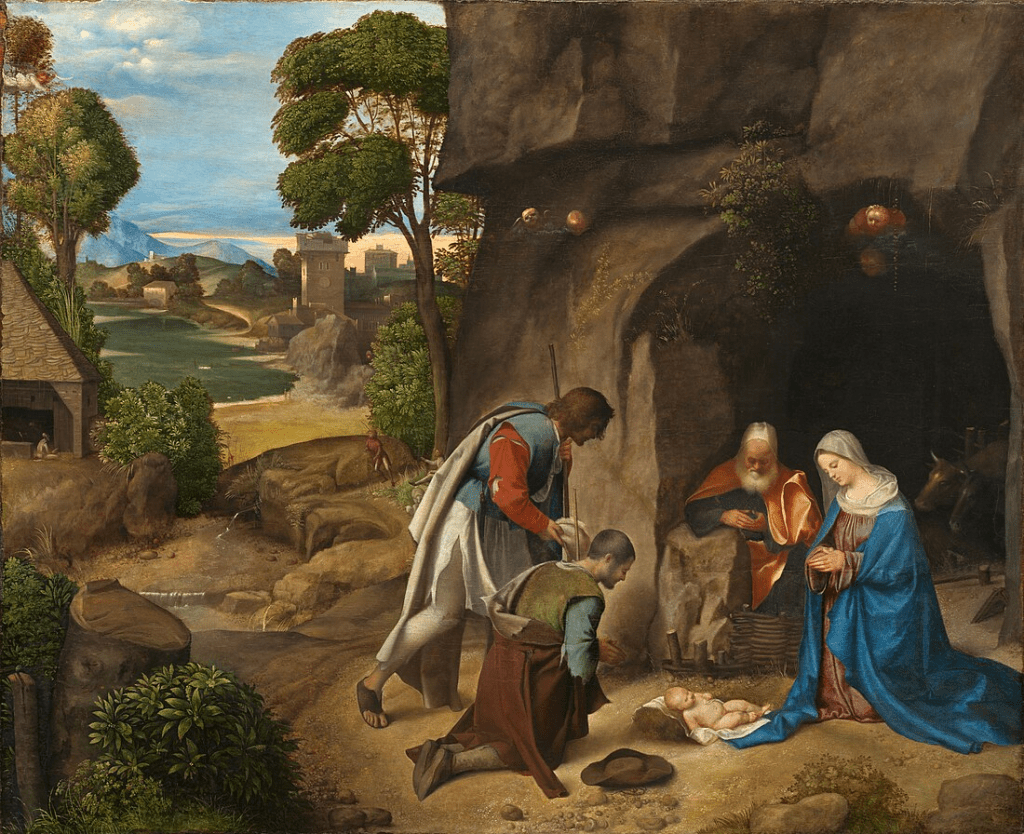

Mozart’s interest in Bach and Handel was atypical, but his familiarity with their vocal-instrumental masterpieces of sacred music became a powerful influence on him. Indeed, the first part of Handel’s 1741 masterpiece Messiah, which is focused on the Nativity, contains the so-called Pifa or Pastoral Symphony, because the shepherds were the first people to whom the newborn Christ was revealed. And Handel chose to use that to invoke a bucolic atmosphere familiar from Classical literature, even though the Palestinian shepherds were nothing like the protagonists of Theocritus’ or Virgil’s idylls.

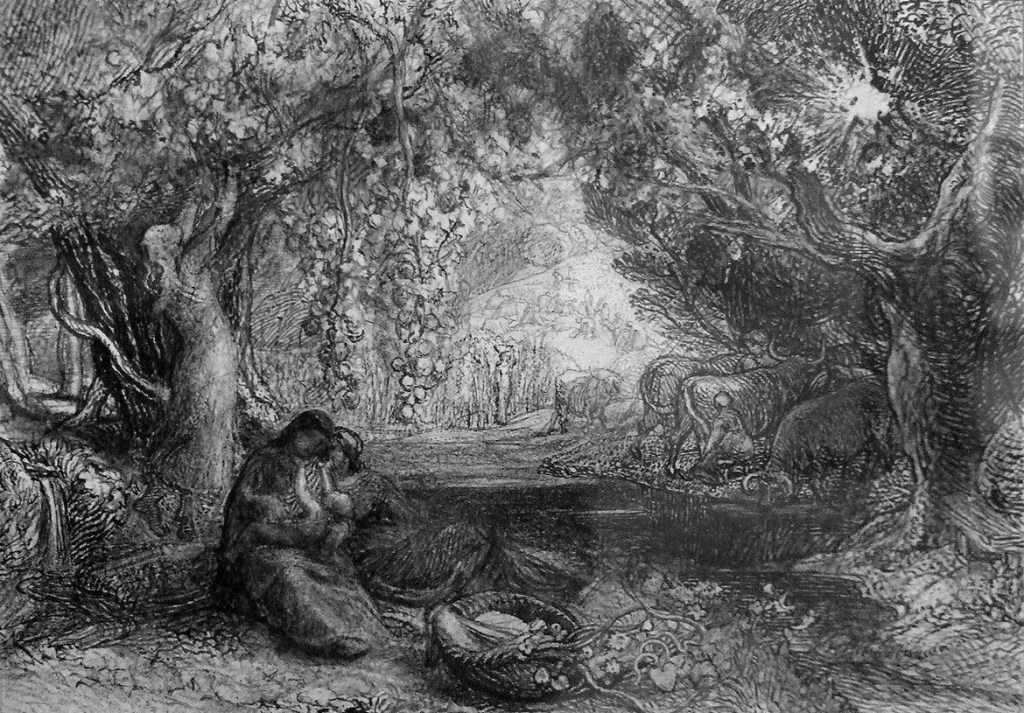

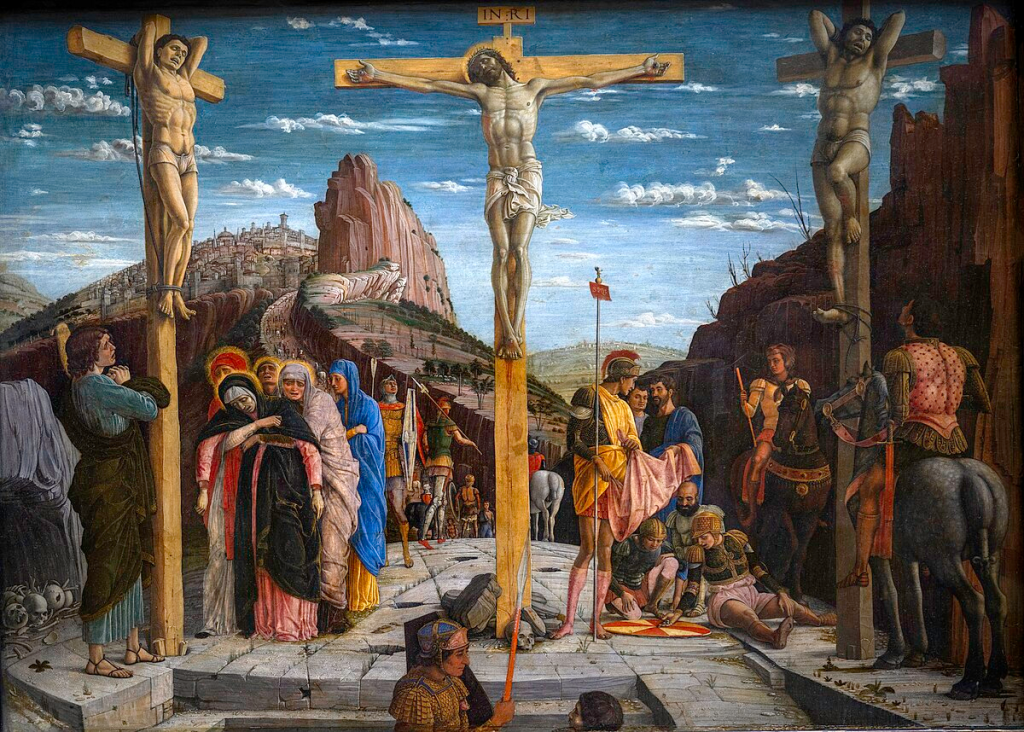

However, it is striking, at the same time, how different Mozart’s springtime bucolic Et incarnatus est is from the way Bach rendered the same part of the Latin Creed in his Great Mass in B Minor. Bach’s Et incarnatus est (composed and added to his 1733 Great Mass only shortly before his death in 1750) seems disorienting: it is a dark, almost unsettling chorus. Of course, Bach never made mistakes in his music, but this piece is really hard to understand. Perhaps it is supposed to be “mysterious”, but there is something more than mystery here; some dark, puzzling depth of God is opening up, which makes one think that the Crucifixion is lurking behind the joy of Bethlehem (and, in fact, Et incarnatus est in Bach’s Great Mass is followed directly by a heart-breaking Crucifixus).

In any case, Mozart’s Et incarnatus est is neither a simple imitation of Handel’s Pastoral Symphony, nor an insolent “No!”, uttered by a rebellious 26-year-old to the outdated musical giant from Leipzig. The aria is very long, and its tempo is slow, so it lasts around eight minutes in a performance. Intriguingly, though, there is no sense of time passing, when the endlessly expanding and revolving soprano phrases seem to unfold in the eternal now rather than occupy any measurable time length.

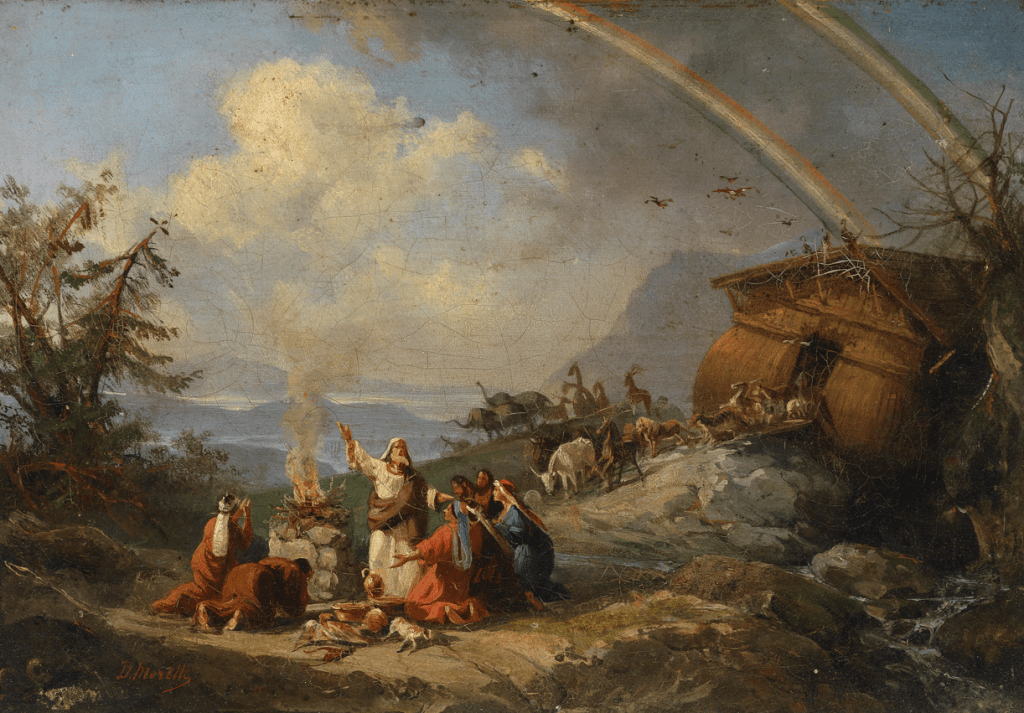

The vocal part repeatedly ascends to heaven and descends back on earth, thus becoming like the covenantal rainbow after the Flood (Genesis 9:13–16), reminding us “of wrath ended / of woes mended” (C.S. Lewis). The rainbow or the Greek messenger-goddess Iris, from a Christian perspective is the Old Testament type (τύπος) or foreshadowing of the God-Man, who unites in Himself heaven and earth, and in whom all things are reconciled (1 Col 1:20). He is the true Olive Branch brought by the Dove from heaven to announce the restoration of all things after the Flood, to announce the eternal spring.

The intensity of the soprano part in Mozart’s Et incarnatus, its relentless, unbearable sweetness, is, naturally, hard to put into words. What musicologists call “exquisite pathos” (Robert Gutman) or “unworldly rapture” (Konrad Küster) brings to mind some kind of delicate, liquid joy, flowing between heaven and earth, eternity and time, divinity and humanity, in a perpetual dialogue with the angelic trio of a flute, oboe, and bassoon. The gentle, feminine warmth of the aria reminds the listener about the Blessed Virgin (iam redit Virgo…) by virtue of the insistence of the sweetly falling, circular phrase ex Maria Virgine. We can almost imagine the Virgin singing that Magnificat of joy, thankfulness, and praise in the silence of her meditating heart (Luke 2:19).

The sheer miracle of that aria cannot be, of course, explained by any biographical or historical context. And yet, the context is there, and it is telling. Shortly before the planned wedding of the 26-year-old Wolfgang with the nineteen-year-old soprano Constanze Weber, she fell ill. Mozart was already worrying whether his father, Leopold, would allow their marriage, and now he also had reasons to fear for her life. The composer made a promise that, if she recovered and married him, he would compose a great mass to thank God for that. After Constanze got well and they were married on 4 August 1782 in Vienna, Mozart began to work on the mass, which he couldn’t finish, just like he couldn’t finish his second liturgical masterpiece, the famous Requiem.

The unfinished Great Mass in C Minor was nevertheless performed in Saint Peter’s Abbey church in Salzburg in October 1783, with Constanze herself singing the soprano part. Mozart says in one of his letters that she came to love Bach and Handel when he was immersing himself in the study of their sacred music. Not only did the Great Mass testify to their shared fascination with the two great Baroque predecessors: also, when Mozart was composing Et incarnatus est, he probably imagined the voice of his newly-wedded wife, who was already pregnant with their first son, Raimund Leopold – who was, tragically, to die in infancy. Constanze had to sing the aria only two months after losing her first child.

The transcendent, divine sweetness of the aria may have descended straight from Heaven, but the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation teaches that the divine reveals itself in what is most human, since “the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.” It was in that spirit that Et incarnatus est was composed, by a flesh-and-blood man for his beloved wife during their honeymoon; it was composed in a spirit of gratitude for the gift of their marriage and the gift of their first child, and in ignorance of the coming, inevitable crucifixion.

But even if the crucifixion is always due at some point, the mother smiles with a spring-time exuberant joy at her newborn son:

incipe, parve puer, risu cognoscere matrem,

matri longa decem tulerunt fastidia menses.

incipe, parve puer, cui non risere parentes,

nec deus hunc mensa, dea nec dignata cubili est. (Ecl. 4.60–3)

Begin to greet thy mother with a smile,

o baby-boy! ten months of weariness

for thee she bore: O baby-boy, begin!

For him, on whom his parents have not smiled,

gods deem not worthy of their board or bed.

Mateusz Stróżyński is a Classicist, philosopher, psychologist, and psychotherapist, working as an Associate Professor in the Institute of Classical Philology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. He is interested in ancient philosophy, especially the Platonic tradition. His most recent books are The Human Tragicomedy: the Reception of Apuleius’ Golden Ass in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Century (ed., Brill, Leiden, 2024) and Plotinus on the Contemplation of the Intelligible World: Faces of Being and Mirrors of Intellect (Cambridge UP, 2024).

Notes

| ⇧1 | Augustine of Hippo, Sermons. The Works of Saint Augustine. A Translation for the 21st Century, Part III, vol. 6, transl. E. Hill OP (New City Press, New Rochelle, NY, 1993) 26, n.8. |

|---|