Carey Jobe

His busy schedule of public speaking had exhausted him. Dio of Prusa, later surnamed Dio Chrysostom (“Golden-Mouthed”), needed a day off. Always intent on self-improvement, he decided to use it constructively. He describes his morning:

᾽Αναστὰς σχεδόν τι περὶ πρώτην ὤραν τῆς ἡμέρας καὶ διὰ τὴν ἀρρωστίαν τοῦ σώματος καὶ διὰ τὸν ἀέρα ψυχρότερον ὄντα διὰ τὴν ἕω καὶ μάλιστα μετοπώρῳ προσεοικότα καίτοι μεσοῦντος θέρους, ἐπεμελήθην ἐμαυτοῦ καὶ προσηξάμην. ἔπειτα ἀνέβην ἐπὶ τὸ ζεῦγος καὶ περιῆλθον ἐν τῷ ἱπποδρόμῳ πολλούς τινας κύκλους, πρᾴως τε καὶ ἀλύπως ὡς οἷόν τε ὑπάγοντος τοῦ ζεύγους. καὶ μετὰ ταῦτα περιπατήσας ἀνεπαυσάμην μικρόν τινα χρόνον. ἔπειτα ἀλεϊψάμενος καὶ μικρόν ἐμφαγὼν ἐνέτυχον τραγῳδίαις τισιν.[1]

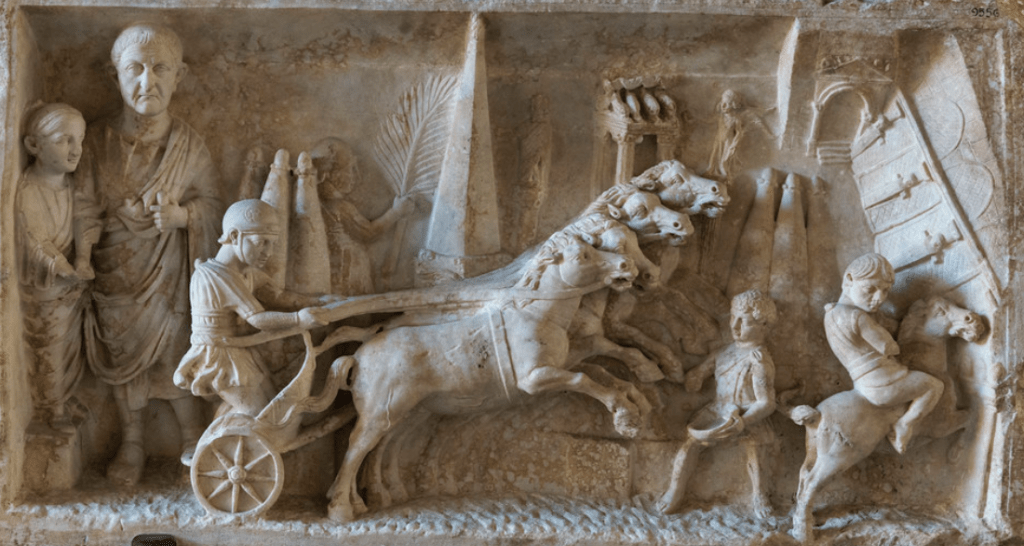

After rising at almost the first hour of the day because of my body’s illness and the chilly pre-dawn air, which felt autumn-like though it was mid-summer, I dressed and prayed. Then I got in my carriage and rode around the hippodrome a few times, my horses moving along at a gentle, easy pace. Afterward I took a stroll, then rested awhile. Then, after a rubdown and light breakfast, I looked up certain tragedies.[2] (Discourse 52.1)

Dio devoted the remainder of his “sick day” to a comparative reading of the three plays titled Philoctetes by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. He summarized his day of literary criticism in his 52nd Discourse: On Aeschylus and Sophocles and Euripides, or, The Bow of Philoctetes.

Philosopher, author, orator, friend of emperors, Dio “Chrysostom” was born in Prusa, a city in Roman Bithynia, about AD 40. His father, a wealthy city magistrate, ensured that Dio received a thorough education emphasizing literature, philosophy and rhetoric. With this training and his “golden” oratorical talents, by the reign of Vespasian Dio was established in Rome as a successful rhetorician and philosopher.[3]

Dio’s career halted when he was implicated in a plot against the emperor Domitian (ruled AD 81–96). Exiled from Italy and his native Bithynia, Dio spent the next fourteen years in poverty wandering the fringes of the Roman Empire, earning a livelihood however he could. His exile ended upon Domitian’s assassination in 96. He resumed his career and regained imperial favor, becoming a friend to Trajan and spending his remaining years as a respected philosopher, public speaker, and benefactor of Prusa, until his death around 120 AD.

He wrote voluminously. His best-known works are eighty Discourses – dialogues and moral exhortations on a variety of civic and philosophical themes. These discourses offer valuable insight into Dio’s life, his era, and his views. Secluded in his villa, Dio now imagined himself in 5th-century Athens witnessing a tragic competition at the City Dionysia.[4] But instead of one playwright staging three tragedies, as was customary, Dio’s competition involved one tragedy, Philoctetes, composed by three tragedians – the masters of Athenian tragedy:

… αὐτὸς δὲ ἐφαινόμην ἐμαυτῷ πάνυ τρυφᾶν καὶ τῆς ἀσθενίας παραμυθίαν καινὴν ἔχειν. οὐκοῦν ἐχορήγουν ἐμαυτῷ πάνυ λαμπρῶς καὶ προσέχειν ἐπειρώμην, ὥσπερ δικαστὴς τῶν πρώτων τραγικῶν χορῶν.

… So it seemed I had found a way to pamper and enjoy myself despite my illness. Hence, I provided myself with a splendid experience, and I tried to pay close attention, like a judge of the first tragic choruses.” (Discourse 52.3).

We can understand why the Philoctetes legend was in Dio’s mind. Like the famed archer of mythology, Dio had risen to prominence in his society only to be banished, and then after many years recalled to his country’s service.

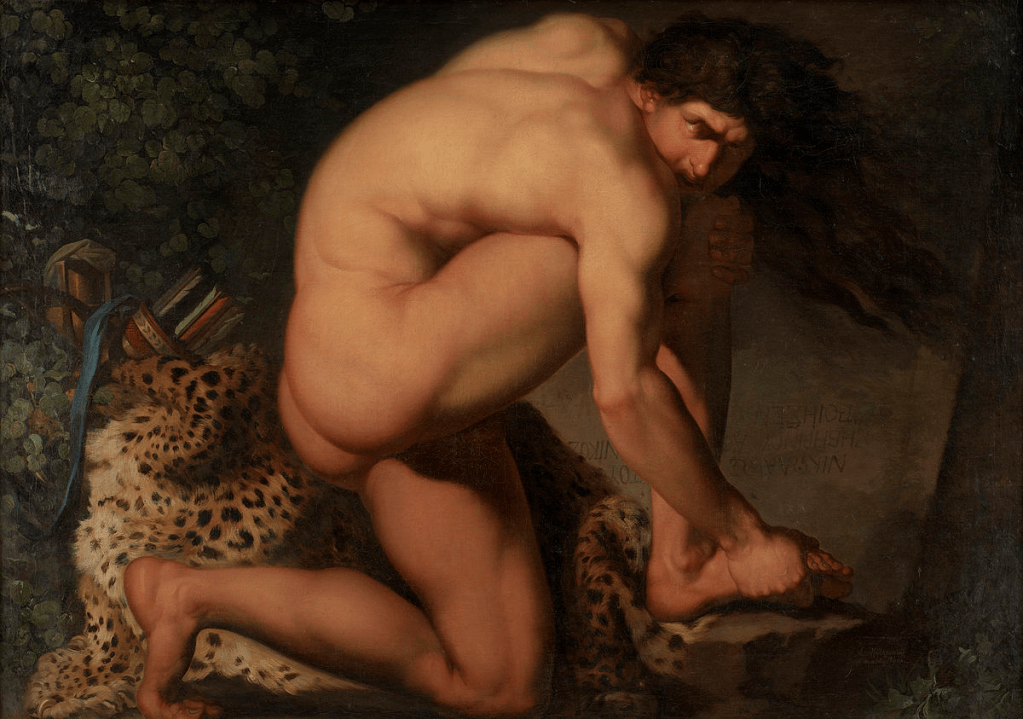

Philoctetes received the bow and arrows of Heracles, unerring weaponry that once belonged to Apollo, as reward for kindling the hero’s funeral pyre.[5] He was chosen as a Greek commander at the start of the Trojan War.

While sailing to Troy, he was bitten by a snake for trespassing on the shrine of the nymph Chryse. The agonizing wound never healed. The wound’s stench and Philoctetes’ cries of pain proved so disturbing that, on the advice of Odysseus, the Greeks abandoned him on the island of Lemnos. For ten years he led a destitute life, wracked by pain, surviving only by hunting with his bow.

During those ten years, Greeks and Trojans battled to a bloody stalemate. When the Greeks captured Helenus, son of Priam and a Trojan priest, he disclosed the prophecy that Troy could be conquered only with the bow of Heracles. The Greeks organized an expedition to Lemnos to retrieve the bow by any means necessary.[6]

Dio begins by reading the Philoctetes of Aeschylus, the earliest play of the three.[7] In adapting the epic legend for the stage, Aeschylus heightened dramatic tension by altering the Homeric account that Diomedes led the Lemnos expedition (Iliad 2.723); he made Odysseus, the instigator of Philoctetes’ exile, the leader of the mission to retrieve him.

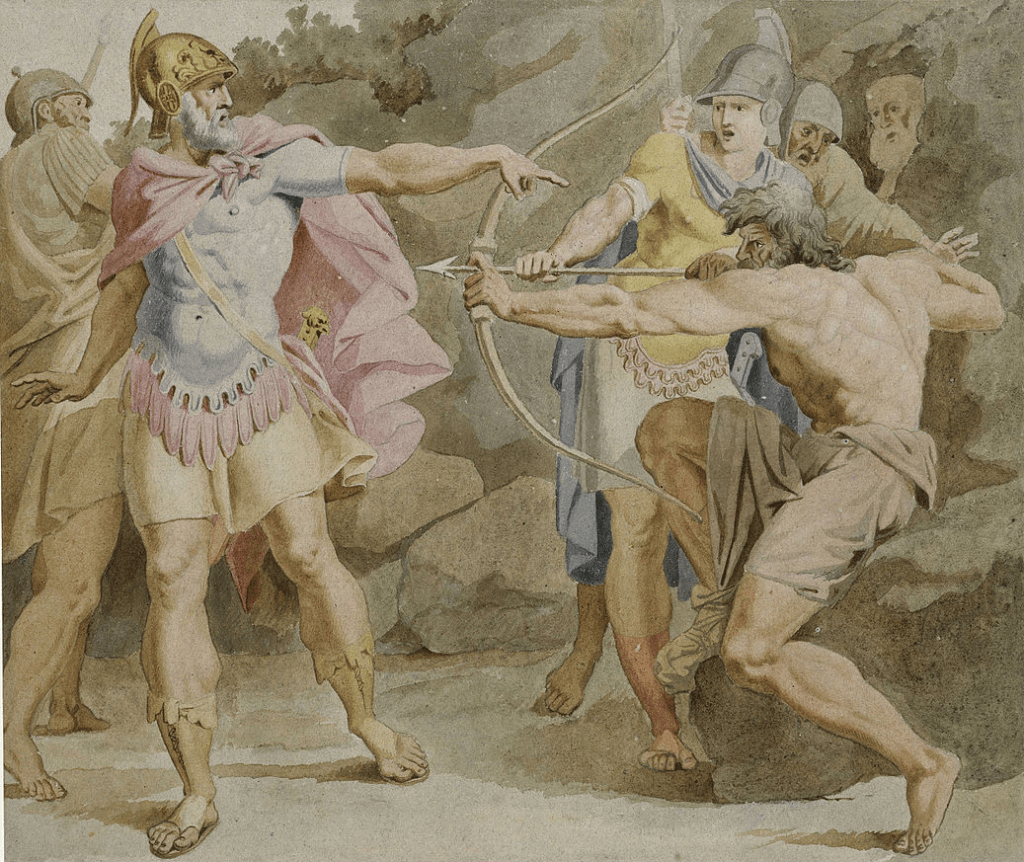

Aeschylus’ uncomplicated plot established the narrative framework used by the later tragedians. Odysseus approaches Philoctetes but is unrecognized. He pretends to be a fugitive from the Greek army and gains Philoctetes’ trust by falsely reporting disaster and dissension had befallen the Greeks. Philoctetes’ wound causes a paroxysm of pain, during which Odysseus seizes the bow and reveals his identity and mission. He persuades Philoctetes to accompany him to Troy without need of “intricate trickery or stratagems” (ποικίλης τέχνης καὶ ἐπιβουλῆς, poikilēs tekhnēs kai epiboulēs).

Dio praises Aeschylus’ play for its μεγαλοφροσύνη (megalophrosunē, lofty tone), ἀρχαῖον (arkhaion,antique style), and αὔθαδες τῆς διανοίας καὶ φράσεως (authades tēs dianoiās kai phraseōs, rugged ideas and diction) – qualities he considered well-suited to the manners of the heroic age. Odysseus was “shrewd and crafty” (δριμὺν καὶ δόλιον, drīmun kai dolion), as in Homer, but without the “baseness” (κακοηθείας, kakoētheiās) that Dio says characterized the people of his own day.

Quotations from ancient sources provide a sense of the rough-hewn nobility that Dio admired in Aeschylus’ play. During the spasm of his wound, Philoctetes’ cry of pain becomes prayer-like, as he calls on Death as deliverer:

ὦ θάνατε παιάν, μή μ’ ἀτιμάσῃς μολεῖν‧

μόνος γὰρ εἶ σὺ τῶν ἀνηκέστων κακῶν

ἰατρός, ἄλγος δ’ οὐδὲν ἅπτεται νεκροῦ.[8]

Oh Death the Savior, do not scorn me, come!

You only are for evils beyond cure

the healer, and no pain can touch the dead.

Odysseus dignifies his deceptions as divinely sanctioned:

ψευδῶν δὲ καιρὸν ἔσθ’ ὅπου τιμᾷ θεός.

There comes a time when falsehoods honor god.

In discussing the play, Dio frequently contrasts Aeschylus’ old-fashioned style with the more sophisticated techniques of Euripides. Was the Aeschylus versus Euripides contest of Aristophanes’ Frogs (405 BC) in his mind? If so, the scales are weighted: as he turns to the Philoctetes of Euripides, Dio gushes with admiration:

Ἥ τε τοῦ Εὐριπίδου σύνεσις καὶ περὶ πάντα ἐπιμέλεια, ὥστε μήτε ἀπίθανόν τι καὶ παρημελημένον ἐᾶσαι μήτε ἁπλῶς τοῖς πράγμασι χρῆσθαι, ἀλλὰ μετὰ πάσης ἐν τῷ εῖπεῖν δυνάμεως, ὥσπερ ἀντίστροφός ἐστι τῇ τοῦ Αἰσχύλου, πολιτικωτάτη καὶ ῥητορικωτάτη οὖσα καὶ τοῖς ἐντυγχάνουσι πλείστην ὠφέλειαν παρασχεῖν δυναμένη.

The sagacity of Euripides and his care for every detail is such that he permits nothing that seems improbable or carelessly planned, treating the action not in a haphazard way, but handling all with powerful mastery – this makes him the opposite of Aeschylus, reflecting to the highest degree good citizenship and rhetoric, and capable of providing the greatest benefit to those who read him.” (Discourse 52.11)[9]

The Philoctetes of Euripides was produced at the City Dionysia in 431 BC as part of a tetralogy that included the extant Medea, Dictys, and the satyr play Theristai, winning third prize.[10] Notably, the year 431 BC also marked the start of the Peloponnesian War, a conflict that possibly influenced Euripides’ treatment of this wartime legend.[11]

Euripides’ play, Dio says, was distinguished by its precision (ἀκριβές, akribes), incisiveness (δριμύ, drīmu), and political relevance (πολιτική, politikē). Building on the Aeschylean plot, Euripides added new characters, novel complications, and realistic details. His characters have complex motivations: Odysseus delivers a Prologue (paraphrased separately by Dio in Discourse 59) in which he explains to the audience why he is jeopardizing his reputation for wisdom by volunteering to lead the risky mission to Lemnos.

Philoctetes hates him and would gladly kill him. He confesses he is driven by ambition–the need to increase his fame by performing new deeds of shrewdness and heroism:

οὐδὲν γὰρ οὕτω γαῦρον ὡς ἀνὴρ ἔϕυ.[12]

For there is nothing quite so proud as man.

In a realistic touch, Euripides brings Philoctetes onstage dressed in animal skins, his shabby appearance later satirized by Aristophanes (Acharnians 424). He has settled into a hermit life on Lemnos and shows no inclination to leave. He has a Lemnian friend, the shepherd Actor, who supports him during the course of the play. He harbors bitterness toward all Greeks: he threatens to kill Odysseus (his appearance disguised by Athena) just for saying that he is Greek, sparing him only when he pretends to be a fugitive soldier who despises the Greek commanders as much as Philoctetes (Discourse 59.7).

Just as Aeschylus did, Euripides makes a bold alteration to the legend: an embassy from Troy now arrives at Lemnos, its purpose to lure Philoctetes to Troy and thereby prevent the Greeks from acquiring Philoctetes’ bow (Discourse 52.13, 59.4).

Dio finds Euripides’ play noteworthy for its lively debate scenes. The plot’s complexities, he says, served as “a starting point for debates” (λόγων ἀφορμάς, logōn aphormās, Discourse 52.13). Surviving quotations give the flavor of one such debate, the “contest for Philoctetes” waged between Odysseus and the Trojans.

The Trojans try to entice Philoctetes by offering wealth:

ὁρᾶτε δ’ ὡς κἀν θεοῖσι κερδαίνειν καλόν,

θαυμάζεται δ’ ὁ πλεῖστον ἐν ναοῖς ἔχων

χρυσόν. τί δῆτα καὶ σὲ κωλύεί λαβεῖν

κέρδος, παρόν γε κἀξομοιοῦσθαι θεοῖς;

Look how the gods do not disdain a profit,

for who heaps up the most gold in his temple

is most admired. What stops you then from gaining

riches to raise you equal to the gods?

Odysseus (his identity still concealed) begins his rebuttal by appealing to Philoctetes’ patriotism and Greek antipathy for “barbarian” Trojans:

ὑπέρ γε μέντοι παντὸς Ἑλλήνων στρατοῦ

αἰσχρὸν σιωπᾶν, βαρβάρους δ᾽ ἐᾶν λέγειν.

How shameful is it that the whole Greek army

is silent, yet barbarians may speak!

The Trojans disclose the prophecy of Helenus (which Philoctetes would be hearing for the first time); Odysseus counters by discrediting all prophets:

τί δῆτα θάκοις μαντικοῖς ἐνήμενοι

σαφῶς διόμνυσθ’ εἰδέναι τὰ δαιμόνων;

οὐ τῶνδε χειρώνακτες ἄνθρωποι λόγων.

ὅστις γὰρ αὐχεῖ θεῶν ἐπίστασθαι πέρι

οὐδέν τι μᾶλλον οἶδεν ἢ πείθειν λέγων.

What can those boasting their oracular gifts

truly reveal concerning things divine?

I say they only wring their hands and talk.

Whoever brags he understands the heavens

merely knows how to sway the gullible.

We know Philoctetes ultimately rejects the Trojans, but Dio tells us little about the play’s conclusion other than stating that Philoctetes accompanies Odysseus to Troy “partly willingly, partly compelled by necessity” (τό μὲν πλέον ἑκών, τό δέ τι καὶ πειθοῖ ἀναγκαίᾳ, to men pleon hekōn, to de ti kai peithoi anangkaiāi). A final debate on the question could have occurred between Odysseus and Philoctetes’ friend Actor. But “compelled by necessity” implies that Odysseus’ seizure of the bow during Philoctetes’ paroxysm was a crucial factor in Philoctetes’ decision. Deprived of his means of survival, Philoctetes would have confronted a fait accompli, finding himself, as with his initial abandonment, a victim of Odysseus and the ugly choices of war. If this was indeed the play’s ending, Euripides’ Philoctetes would have concluded on an unsettling note, much like its companion play Medea.[13]

Dio finishes his play-reading with the Philoctetes of Sophocles, the one member of this “trilogy” that we can still read. Sophocles’ Philoctetes was performed in 409 BC, winning first prize.[14] Writing over two decades after Euripides, Sophocles, too, adapted the Aeschylean plot in an original way, creating a psychological atmosphere as different from Euripides’ play as their two versions of Electra.

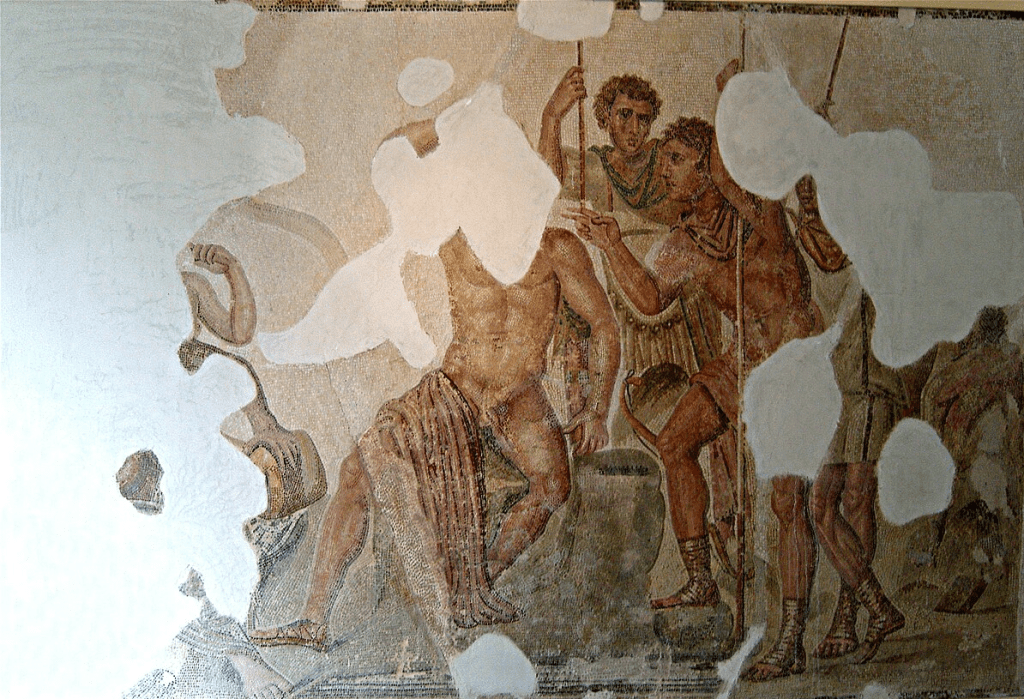

Sophocles places the action in a scene of immense isolation: Lemnos is now uninhabited. Odysseus now arrives accompanied by Neoptolemus, son of the slain Achilles.[15] Odysseus assigns to Neoptolemus the distasteful task of deceiving the wounded archer.

After ten years of solitude, impoverishment, and suffering, the Philoctetes of Sophocles is remarkably lacking in bitterness. Unlike the antisocial Philoctetes of Euripides, he is overjoyed to meet Neoptolemus and hear Greek spoken. Despite the lies he must tell, Neoptolemus feels compassion for Philoctetes and desires to help him, while simultaneously wrestling with his patriotic duty to betray this sympathetic figure.

The climax of Neoptolemus’ dilemma occurs when Philoctetes trustingly hands the bow to him during the spasm of his wound. His mission achieved, Neoptolemus – astonishingly – returns the bow in answer to Philoctetes’ desperate pleas. Odysseus reappears and accuses Neoptolemus of treason. Clashing moral demands reach an impasse until Heracles appears as deus ex machina and announces that Philoctetes is destined to go to Troy, where he will achieve glory, and his wound will be healed. Obedient to his patron deity, Philoctetes sails to Troy.

Dio felt Sophocles’ play occupied a middle ground between the other two plays. It lacked the rugged simplicity of Aeschylus and the keen-edged rhetorical verve of Euripides. Still, the characters were “wonderfully dignified and high-minded” (θαυμαστῶς σεμνὰ καὶ ἐλευθέρια, thaumastōs semna kai eleutheria). Neoptolemus was portrayed as a person of honesty (ἁπλότης, haplotēs) and good breeding (εὐγένεια, eugeneia). Sophocles’ poetry was “to the highest degree tragic and eloquent” (τραγικώτατα καὶ εὐεπέστατα, tragikōtata kai euepestata), conveying a “magnificence” (μεγαλοπρέπειαν, megaloprepeian) that left the reader with “surpassing pleasure” (θαυμαστὴν ἡδονὴν, thaumastēn hēdonēn). The briefest of his three critiques, Dio’s praise has a perfunctory tone and leaves the impression that, after a long day reading tragedies, he only skimmed the play.

Yet the praiseworthy qualities Dio notes are readily found throughout the work. A sample of the play’s poetry is its concluding lines, as Philoctetes says farewell to Lemnos (1453–63). His tribute to the harsh but majestic natural world that held him captive foreshadows Prospero’s Farewell in Shakespeare’s The Tempest:

χαῖρ’, ὦ μέλαθρον ξύμφρουρον ἐμοί,

νύμφαι τ’ ἔνυδροι λειμωνιάδες,

καὶ κτύπος ἄρσην πόντου προβολῆς,

οὗ πολλάκι δὴ τοὐμὸν ἐτέγχθη

κρᾶτ᾽ ἐνδόμυχον πληγαῖσι νότου,

πολλὰ δὲ φωνῆς τῆς ἡμετέρας

Ἑρμαῖον ὄρος παρέπεμψεν ἐμοὶ

στόνον ἀντίτυπον χειμαζομένῳ.

νῦν δ’, ὦ κρῆναι Λυκιόν τε ποτόν,

λείπομεν ὑμᾶς, λείπομεν ἤδη

δόξης οὔ ποτε τῆσδ’ ἐπιβάντες. [16]

Goodbye, oh cavern of my vigils,

nymphs that haunt the dew-moist meadows,

and endless thunder of the sea

whose waters often drenched my head

with salt-spray borne on the south wind,

and often Mount Hermaion’s cliffs

echoed my groans again to me

as chorus to my storms of pain.

For now, oh springs and Lycian well,

I leave forever, I set sail

beyond where any hope could go.

Who won the contest? The self-styled judge modestly – and disingenuously – confesses “I could not under oath declare a single reason why any one of those men would have been defeated” (ὀμόσας γε οὐκ ἂν ἐδυνάμην ἀποφήνασθαι οὐδέν, οὗ γε ἕνεκεν οὐδεὶς ἂν ἡττήθη τῶν ἀνδρῶν ἐκείνων, Dialogue 52.2). His own banishment had taught him the risk of openly choosing sides.

Yet Dio’s thinly veiled favoritism is pardonable. He believed that “to become involved in civic affairs and political issues is natural to man” (Discourse 47.2) and that the study of Euripides was “altogether beneficial to a political man” (Discourse 18.7). An orator and active citizen in his society, Dio would be drawn instinctively to the political engagement and rhetorical flair of Euripides – a viewpoint typical for his times, the era of the Second Sophistic school, when Euripides’ plays were studied as models of rhetoric.[17]

A profitable use of a “sick day”! Thanks to Dio’s day with Philoctetes, we can glimpse two lost plays, and we better understand how the classical world viewed the three great tragedians. But despite Dio’s reluctance to crown a victor, it was ultimately time that decided the winner of the contest. Over many centuries, it was the Philoctetes of Sophocles that won that most challenging victory – the victory of survival.

Carey Jobe is a retired attorney and judge. Prior to beginning his legal career, he was a student of Classical Literature and Latin Language. His Latin translations have appeared in Classical Outlook, the journal of The American Classical Society. He is also a widely published poet whose work regularly appears in numerous literary journals. He lives and writes near Tallahassee, Florida. He has previously written for Antigone about the challenge of reconstructing Aeschylus’ lost play Prometheus Unbound.

Further Reading

N. Austin, Sophocles’ Philoctetes and the Great Soul Robbery (Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI, 2011).

T. Bekker-Nielsen, Urban Life and Local Politics in Roman Bithynia: The Small World of Dion Chrysostom (Aarhus UP, 2008).

B. Doerries, The Theater of War: What Ancient Tragedies Can Teach Us Today. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2015).

E. Hall, “Ancient Greek responses to suffering: thinking with Philoctetes,” in J. Malpas & N. Lickiss (edd.), Perspectives on Human Suffering (Springer, New York, 2012) 155–69.

M.H. Jameson, “Politics and the Philoctetes,” Classical Philology 51 (1956) 217–27.

C.P. Jones, The Roman World of Dio Chrysostom (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 1978).

H. Sidebottom, “Dio of Prusa and the Flavian dynasty,” Classical Quarterly 46 (1996) 447–56.

S. Swain, Dio Chrysostom: Politics, Letters, and Philosophy (Oxford UP, 2000).

Notes

| ⇧1 | The Greek texts of Dio Chrysostom used in this article are taken from the Loeb Classical Library: Dio Chrysostom vol. 4 (ed. J.W. Cohoon, 1946) 336–54. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | This translation, and all other translations in the piece, are by the author. |

| ⇧3 | These details of Dio’s life derive from his Discourses, principally Discourses 3, 12, 13, 45, and 46. |

| ⇧4 | The City Dionysia was an annual festival in Athens in honor of Dionysus. Three playwrights participated in the festival’s tragic competition, each presenting three tragedies and a satyr play. |

| ⇧5 | The legend of Philoctetes is first mentioned by Homer in the Catalogue of Ships (Iliad 2.718–23). Further details of the legend, with varying details, were told in now-lost poems of the Epic Cycle (the Little Iliad, Cypria, and Iliou Persis). |

| ⇧6 | As the legend continues, once at Troy Philoctetes’ wound was healed by the sons of the famed physician Asclepius. Philoctetes’ bow, as prophesied, proved crucial in the capture of Troy. |

| ⇧7 | The date of Aeschylus’ Philoctetes is unknown, but an excellent analysis suggests that it dates from 484–472 BC, early in the history of Greek tragedy. See W.M. Calder, III, “Aeschylus’ Philoctetes,” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 11.3 (1970) 171–9. |

| ⇧8 | Both Aeschylus quotations are taken from the Loeb Aeschylus, vol. 2 (ed. H. Lloyd-Jones, 1971) at pp. 467 and 479. |

| ⇧9 | Dio admired the play so greatly that, in addition to the discussion in Discourse 52, he paraphrased much of the play’s opening scene in Discourse 59. |

| ⇧10 | Euripides’ 431 BC trilogy is mentioned in the ancient hypothesis to Medea. |

| ⇧11 | For a discussion of the background and probable plot of the play, see S.D. Olson, “Politics and the Lost Euripidean Philoctetes,” Hesperia 60.2 (1991) 269–83. |

| ⇧12 | The Euripides quotations are from the Loeb Classical Library, Euripides vol. 8 (edd. C. Collard and M. Cropp, 2008), at pp. 384, 397 and 399. |

| ⇧13 | For discussion of this proposed conclusion, see Olson (as n.11) 281–2. |

| ⇧14 | Our knowledge of the winners at the City Dionysia comes primarily from ancient inscriptions referred to as the Fasti, the Didascaliae, and the Victors List. |

| ⇧15 | A dramatically fraught character choice, as the legend held that the participation of Neoptolemus was also necessary to conquer Troy, and because the Arms of Achilles, which belonged to Neoptolemus by inheritance, were instead awarded to Odysseus. |

| ⇧16 | Loeb Classical Library, Sophocles vol. 2 (ed. H. Lloyd-Jones, 1978), p. 491. |

| ⇧17 | For a contemporary view of the Second Sophistic, see Philostratus’ Lives of the Sophists. (Trans. W.C. Wright, Harvard University Press, 1961). |