Paul McKenna

Last year Neil W. Bernstein published The Complete Works of Claudian: Translated with an Introduction and Notes (Routledge, London, 2023).[1] This is a welcome addition to scholarship on a writer from late antiquity who still remains on the edge of the common canon. In the past, Anglophones have been dependent on Platnauer’s 1922 Loeb: it was perfectly reliable for many years but his translation is somewhat ‘of its time’, and I suppose that a new generation of readers deserves a translation to which they can relate more readily. However, the book’s author (as well as his BMCR reviewer) has missed an important point: Claudian was one of a very small group of ancient writers to have works passed down to the present in both Latin and Greek. Therefore this collection should more correctly be called The Complete Latin Works of Claudian…

Claudian’s Greek output includes seven epigrams in the Anthologia Palatina (two in Book 1, one in Book 5, and four in Book 9) and an incomplete mythological epic on the battle of the giants, commonly known by a Greek compound word, gigantomachia. The epigrams are already available in many bilingual texts but there is no such thing readily available for the mythological poem and, as far I am aware, no full English translation anywhere. This short paper repairs both deficiencies.

Ahead of the translation and text we should outline whatever facts about Claudian we can: he was a native Greek-speaker from Egypt whose short life (AD c.370–404) spanned the reigns of the emperors Arcadius and Honorius.[2] He moved to Rome before the turn of the century where he became a trusted and admired court poet. He is perhaps best known for being ‘puffer-up-in-chief’ of those whose favour he courted. His panegyrics have been much delved by historians. Although we may assume that the broad facts are true, the very nature of the panegyric genre implies that we must exercise caution regarding the veracity of the minutiae: better points are pressed to the full whilst any less favourable facts will be passed over without comment.

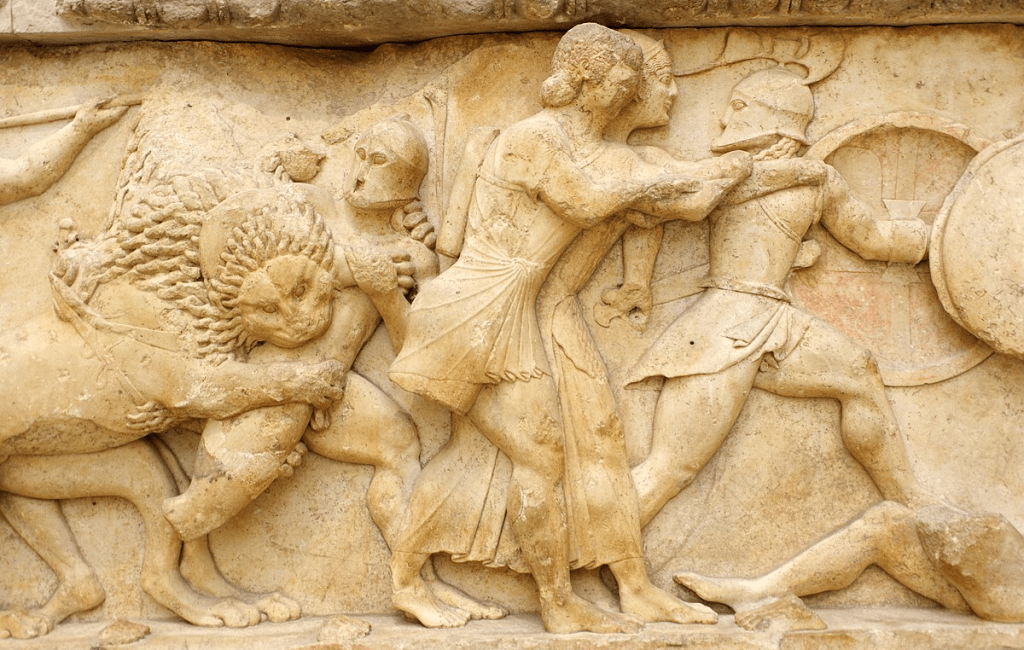

It is an easy criticism to make that Claudian’s poems are a bit too cloying for many modern tastes. Still, they do exist and we should be grateful for that. We must endeavour to study them on their own terms without importing our own literary prejudices. On the other side of the same coin are his invectives against those whose favour he did not court. Criticism of someone’s enemy amounts to indirect praise of that someone. Again, cast aside any twenty-first-century sensibilities and immerse yourself in some hard-hitting rhetoric. His most studied Latin poem, also incomplete like the Greek Gigantomachia, is the mythological epic De raptu Proserpinae, a longish hexameter poem of three books on the troubles endured by Persephone. He also wrote a Latin Gigantomachia and a series of shorter occasional poems, the carmina minora – all are eminently readable and enjoyable.

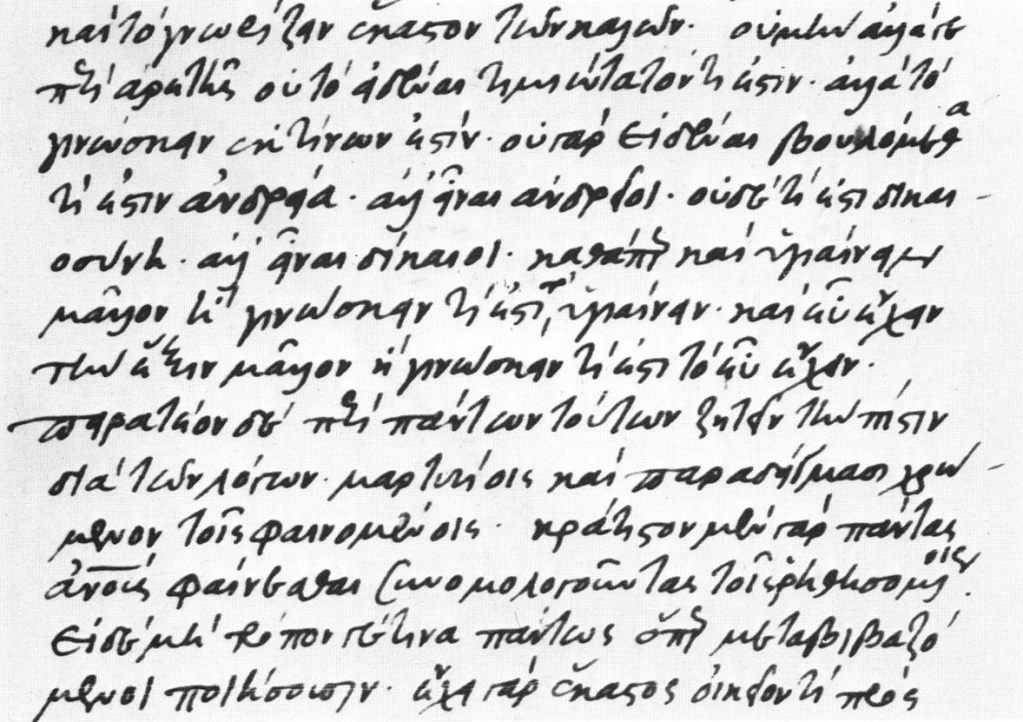

What can we say about his Greek Gigantomachia? It is incomplete, whether unfinished or having suffered fragmentation over time we cannot say; perhaps both. It consists now of 77 hexameter verses. The first seventeen are a proem which forms an invocation to a god; we can tentatively assume that this is the beginning of the poem. I say tentatively, since it is possible, I suppose, that it is a second proem after some earlier narrative (compare the second programmatic proem in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca at 25.1–30). Then we have a gap – or lacuna – which Constantine Lascaris in the 15th century deemed to be of about 70 verses, based on codicological grounds. The remainder is concerned with an account of some events of the battle. Where our text breaks off does not in any meaningful way constitute the end of the poem as we would expect.

The text survives in just five manuscripts. In each of them omissions, additions, misplaced verses, alternative spellings, incorrect spellings, and glosses (collectively known as variant readings) allow scholars to predict which manuscript was copied from which and which was not. Careful consideration of these variants has allowed textual critics to construct a stemma codicum, or manuscript family tree. The conclusion is that four manuscripts are related to each other in a straight chronological line whilst the other one stands alone. The manuscripts therefore form what is known as a ‘bifurcated tradition’.

The current critical edition is J.B. Hall’s Claudii Claudiani Carmina (Teubner, Leipzig, 1985).[3] The text which I offer here is Hall’s, incorporating one or two conjectures from Livrea and Zamora. On the sliding scale of translation from poor translationese to free paraphrase, I hope my translation sits just above the mark of agreeable English, that is to say suitable for Greekless readers to understand, but close enough to the Greek for early learners to follow. More confident readers and scholars should look at Hall’s text and the apparatus criticus for the full picture.

In a follow-up paper I will discuss the text in greater detail and investigate the use of references to the Gigantomachia by other poets as a recusatio (an excuse to avoid writing epic poetry) despite the apparent lack of our having any extant text which does describe the battle fully. Other useful studies could include: a literary-historical investigation into whether the ‘Latin’ Claudian did indeed write these Greek poems and whether they were produced before, during, or after his Latin works (neither point is resolved conclusively, though the mostly tacit assumption is that he did and that he stopped writing Greek after he went to Rome); a wide-ranging investigation into the trope of a poet-sailor in proems would be enjoyable and instructive; reconstruction of the mythology; and, of course, nowadays the reception of any author into later literature and art is always welcome.

In the meantime, I offer a translation, followed by the Greek text:

If ever it came to me, sailing the blue-eyed sea and my mind amazed at the surging deep of the sea, to pray to the Blessed Ones in the sea, and after my voice had flown the wind-driven waves were calmed, the noise of the wind lessened and the sailor rejoiced 5 seeing the help of a great god being on hand. Thus even now, Didymus (for you are god of song) I shall pray for a gracious in-bound voyage of welcome words.

Be gracious and hear me, since when you’re favourable the least fear is in more agreeable hope. 10 For as the sea stretched out from Alexander’s city and many waves of people rose up upon themselves, I then a skilful poet, a Muse-serving sailor, trusting to the Heliconian ship make straight for the contest and I bring a poetic cargo. 15 If the gods are willing may praise inspire my songs by your counsel.

* * *

Gaia sent … into the impious broad heaven and all the ash became scattered having encountered a thunderbolt. One male stood facing Helios threatening 20 to grasp him looking with a slanting eye. He sent a ray to him and a mist hid his glances. The fools did not see the end of the struggle, but they were buried falling by those strikes which they repeatedly suffered.

A parched giant — he wanted to drink the much-flowing water — 25 stretched his wide-yawning throat towards a distant river, he pulled all the water from the rolling stream until he received the myriad water of the streams, following on to the mouth of the devastated river. Again another man, falling headfirst onto the waves of the sea 30 drank the liquid through his mouth. The salty swell gushed in his throat going through the mouth of Nereus. With the deep drunk and water done for, a great depth was exposed and the sea became dry.

Two Earthborns fought against the youth bright-eyed Atrytone; 35 one carried the top of a mountain and moreover, having grasped a huge rock he lifted it up. The goddess killed them but not by a single fate — through one’s breast she ran an ashen spear, to the other she showed Gorgon’s stone-maker head on the bossed shield; 40 as he saw what she held in her hand his limbs became fixed, he stood like a stone.

Cypris carried neither spear nor weapon but she brought her beauty. Having set a light as a messenger on her eyes first a brooch separated her unplaited hair 45 and gripped twisted locks in a thick bunch, and she underlined her lovely eyes with mascara. Having opened the fine edges of her wafty robe she did not hide the flower of her heaving bosom under a top, but armed her eye for the hunt. For she had 50 a wicker basket as helmet, her spear a breast, an eyebrow her missile, her shield beauty, her weapons limbs, her charm as pain-deliverers. If anyone should cast an eye towards her, he’d be laid low, suffering a missile from her hand, so he died by a spear of Ares in the form of Cypris. Also a cloud of death enveloped him.

Typhos 55 rose up in front of Poseidon. Poseidon struck his chest with a trident, Zeus his head with a thunderbolt.

Enceladus did not avoid the battle, he snatched up an island by its roots which leant against many mountains, he had come up against Zeus threatening terrible things. 60 He was threatening to break up the whole Earth making it a desert, to throw the stars into confusion, and to raze Zeus’ house; such things he was threatening. Mother aroused strength in him offering up a murderous missile, a high island which darkened the light of the sun. On the island 65 were trees and rivers, and both beasts and birds. And then unspeakably great anger struck the lord of the gods, he broke up tightly-packed clouds with his thunderbolts, he poured fiery and unquenchable storms onto Enceladus — he wanted to destroy him. He jumped burning out from the middle of the sea. 70 The rising, boiling sea bubbled terribly around him like beasts. And nor did Kronion dally, after ripping off a rock away from the Lycaonian land he set it on the deadly giant, raging uncontrollably. The island fell upon him, 75 which he himself sent forward into heaven. They wear down the hateful Giants with both fire and an island.

Εἴ ποτέ μοι κυανῶπιν ἐπιπλώοντι θάλασσαν

καὶ φρεσὶ θαμβήσαντι κυκώμενα βένθεα πόντου

εὔξασθαι μακάρεσσιν ἐσήλυθεν εἰναλίοισι,

φωνῆς δεπταμένης ἀνεμοτρεφὲς ἔσβετο κῦμα,

λώφησεν δ’ἀνέμοιο βοή, γήθησε δὲ ναύτης 5

ὀσσόμενος μεγάλοιο θεοῦ παρεοῦσαν ἀρωγήν·

ὣς καὶ νῦν, Διδυμαῖε (σὺ γὰρ θεὸς ἔπλευ ἀοιδῆς),

εὔξομαι εὐδιόωντα κατάπλοον εὐεπιάων.

ἵλαθι καί μευ ἄκουσαν, ἐπεὶ σέθεν εὐμνέοντος

παυρότερον δέος ἐστὶν ἐπ’ ἐλπίσι λωιτέρῃσιν. 10

ὡς γὰρ δὴ πέλαγος μὲν ʼΑλεξάνδροιο πόληος

πάντοθεν ἐκτέταται, τὰ δὲ μυρία κύματα λαῶν

ὄρνυτ’ ἐπ’ ἀλλήλοισιν, ἐγὼ δέ τε δειλὸς ἀοιδὸς

μουσοπόλος ναύτης ʽΕλικωνίδι νηὶ πιθήσας

ἰθύνω πρὸς ἄεθλα, φέρω δ’ ἔπι φόρτον ἀοιδήν. 15

εἰ δὲ θεῶν βουλῇσιν ὑφ’ ὑμείων ἐθελόντων

ἡμετέροις ὕμνοισιν ἐπιπνεύσειαν ἔπαινοι

* * *

εὐρὺν ἐς αἰθέρα πέμπε θεημάχον, ἡ δὲ ῥιφεῖσα

τέφρη γίνετο πᾶσα συναντήσασα κεραυνῷ.

ἄλλος δ’ Ἠελίοιο καταντίον ἵστατ’ ἀπειλῶν 20

μαρψέμεναι λοξῇσι γλήνῃσι δεδορκῶς

τῷ δ’ ἐφέηκ’ ἀκτῖν’, ἀχλὺς δ’ ἐκάλυψεν ὀπωπάς.

νήφρονες, οὐδὲ μόθου τέλος ᾔδεσσαν, ἀλλὰ πεσόντες

αὐταῖς αἷς φορέεσκον ἐτυμβεύοντο βολῇσι.

διψήσας δὲ γίγας (πιέειν θέλε νήχυτον ὕδωρ) 25

τῆλε μάλ’ ἐς ποταμὸν τάνυσεν πολυχανδέα δειρήν,

ἕλκε δὲ χεύματα πάντα κυλινδομένοιο ῥόοιο,

ἄχρι δὲ πηγάων ὑπεδέχνυτο μύριον ὕδωρ

ἑσπόμενος προχοῇσιν ἀπολλυμένου ποταμοῖο.

ἄλλος δ’ αὖτε πεσὼν πρηνὴς ἐπὶ κύματα πόντου 30

πῖνεν ὑπὸ στομάτεσσι ποτόν· κελάρυζε δὲ λαιμῷ

Νηρέος ἁλμυρὸν οἶδμα δι’ ἀνθερεῶνος ὁδεῦον.

πινομένου δὲ βυθοῖο καὶ ὕδατος ὀλλυμένοιο

γυμνῶθη μέγα βένθος, ἐχερσώθη δὲ θάλασσα.

κούρης δ’ ἄντα δύω γλαυκώπιδος Ἀτρυτώνης 35

γηγενέες μάρναντο· φέρεν δ’ ὁ μὲν οὔρεος ἄκρην,

αὐτὰρ ὅ γ’ ἠλίβατον πέτρην ἀνάειρε μεμαρπώς.

τοὺς δὲ θεὴ κατέπεφνε δορυσσόος οὺχ ἑνὶ πότμῳ·

τοῦ μὲν γὰρ στέρνοιο διήλασε μείλινον ἔγχος,

τῷ δ’ ἄρα λαϊνοεργὸν ἐπʹ ἀσπίδος ὀμφαλοέσσης 40

Γοργοῦς δεῖξε κάρηνον· ὁ δ’ ὡς ἴδε, γυῖα πεδηθείς,

ᾗ φέρεν ἐν παλάμῃσιν, ὁμοίιος ἵστατο πέτρῃ.

Κύπρις δ’ οὔτε βέλος φέρεν, οὐχ ὄπλον, ἀλλ’ ἐκόμιζεν

ἀγλαΐην· θεμένη γὰρ ἐπ’ ὄμμασιν ἄγγελον αὐγήν,

πρῶτα μὲν ἀπλεκέας περόνῃ διεκρίνατο χαίτας 45

καὶ πλεκτὰς ἔσφιγξε πυκνῷ περιπλέγματι σειράς,

στίμμεϊ δ’ ὀφθαλμῶν ἐρατοὺς ὑπεγράψατο κανθούς.

λεπτὰς δ’ εὐανέμοιο ῥαφὰς χαλάσασα χιτῶνος

πορφυρέων οὐ κρύπτεν υφ’ εἵμασιν ἄνθεα μαζῶν,

ὄμματος εἰς ἄγρην ὡπλισμένη· εἶχε γὰρ αὐτή 50

πλέγμα κόρυν, δόρυ μαζόν, ὀφρῦν βέλος, ἀσπίδα κάλλος,

ὅπλα μέλη, θέλγητρον ἐν ἄλγεσιν· εἰ δέ τις αὐτῇ

ὄμμα βάλοι, δέδμητο, βέλος δ’ ἀπὸ χειρὸς ἐάσας

ὡς Ἄρεως αἰχμῇ τῇ Κύπριδος ὄλλυτο μορφῇ.

καὶ τὸν μὲν θανάτου νέφος ἔνδυεν· ἀλλὰ Τυφωεύς 55

ὦρτο Ποσειδάωνος ἐναντία· τοῦ δὲ τριαίνῃ

στέρνα Ποσειδάων, Ζεὺς ἤλασε κρᾶτα κεραυνῷ.

Ἐγκέλαδος δ’ οὐ λῆγε μάχης, ἀνὰ δ’ ἤρπασε νῆσον

πρόρριζον πολέεσσιν ἐρειδομένην ὀρέεσσι,

δεινὰ δ’ ἀπειλήσας Ζηνὸς κατέναντα βεβήκει. 60

στεῦτο δὲ γαῖαν ὅλην μὲν ἀναρρῆξαι κενεώνων,

ἄστρα δὲ συγχεῦαι, Ζηνός τε μέλαθρον ἐρύσσαι·

τοιά δʹ ἐπηπείλει. τῷ δὲ σθένος ὤρορε μήτηρ

ἡ μὲν ἀνασχομένη φόνιον βέλος ἠελίου τε

νῆσος ἀνερχομένη σκίασεν φάος· ἐν δὲ τε νήσῳ 65

δένδρεα καὶ ποταμοὶ θῆρές τ’ ἔσαν ὄρνιθές τε.

καὶ τότ’ ἄνακτα θεῶν χόλος ἄσπετος ἐστυφέλιξε·

ῥῆξεν γὰρ πυκινὰς νεφέλας σὺν τοῖσι κεραυνοῖς

ἀσβέστους πυρόεντας ἐπ’ Ἐγκελάδῳ χέεν ὄμβρους

(ἤθελ’ ἀμαλδύνειν)· ὁ δὲ μεσσόθεν ἔκθορε πόντου 70

αἰθόμενος· τῷ δ’ ἀμφὶ περιζείουσα θάλασσα

δεινὸν παφλάζεσκε κυκωμένη ὡς περὶ θῆρας

οὐδὲ Κρονίων λῆγε, Λυκαονίης δ’ ἀπὸ γαίης

πέτρον ἀπορρήξας ὀλοῷ ἐπέθηκε γίγαντι,

ἄσχετα μηνιόων· ἐπὶ δ’ αὐτῷ νῆσος ὄρουσεν, 75

ἥν αὐτὸς προέηκεν ἐς οὐρανόν. ἀμφότερον δέ

καὶ πυρὶ καὶ νήσῳ στυγεροὺς τείρουσι γίγαντας.

Now drifting slowly into retirement from the oil and gas industry, Paul McKenna is delighted to consider himself an independent scholar thinking and writing about Classical literature again. Although Greek epic from Late Antiquity is his most comfortable place, studying Horace and the three Roman elegists alongside their modern emulators is a current joy. His earlier essay on the O Tempora Latin crossword puzzles in The Times can be read here.

Further Reading

Alan Cameron’s Claudian: Poetry and Propaganda at the Court of Honorius (Oxford UP, 1970) is the seminal study on Claudian and his works.

Clare Coombe’s Claudian the Poet (Cambridge UP, 2018) is a general introduction with a full bibliography to guide a reader in whichever direction their interests take them.

Barrie Hall, “Prolegomena to Claudian,” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies Suppl. 45 (1986) lays out the most recent editor’s thoughts on the texts. It includes a fuller description of Lascaris’ reconstruction of the Greek Gigantomachia.

Notes

| ⇧1 | For a review see here. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Suda, Alder κ, 1707 which is conveniently available here. |

| ⇧3 | Both E. Livrea, “La Gigantomachia grega di Claudiano: tradizione manoscritta e critica testuale,” Maia 52 (2000) 415–52, and M.J. Zamora, “La «Gigantomaquia» griega de Claudiano,” Cuadernos di Filología Clásica 3 (1993) 347–75 are valuable articles. |