Richard Rutherford

Despite the recent surge of interest in the epics of the post-Ovidian era – which we are no longer allowed to call the Silver Age of Latin Literature – Valerius Flaccus’ Argonautica is still a minority taste. Ecphrasis, by contrast, is a mainstream critical topic and occasionally even figures in the work of sixth-form students. I shall say a little about both Valerius and ecphrasis before focusing on what seems to me a particularly interesting example in his work.

Valerius Flaccus is mentioned as recently dead by Quintilian, whose work was probably completed in the early 90s AD. In his preface, the poet acclaims the Flavian dynasty, praising Vespasian, Titus and Domitian with appropriate compliments, but thereafter the reader is plunged into the world of mythology. The epic which follows narrates the quest of Jason and the Argonauts, but is incomplete, breaking off in the eighth book after 500 lines when Jason has left Colchis with the fleece and Medea.

Most critics are agreed that the poet probably intended to complete the story in eight books, twice the number composed by his Greek predecessor Apollonius of Rhodes. We cannot reconstruct the unwritten portion, but it seems unlikely he would have gone beyond the arrival of the heroes back in Greece, the endpoint reached by Apollonius. This is relevant to the passage I shall discuss below.

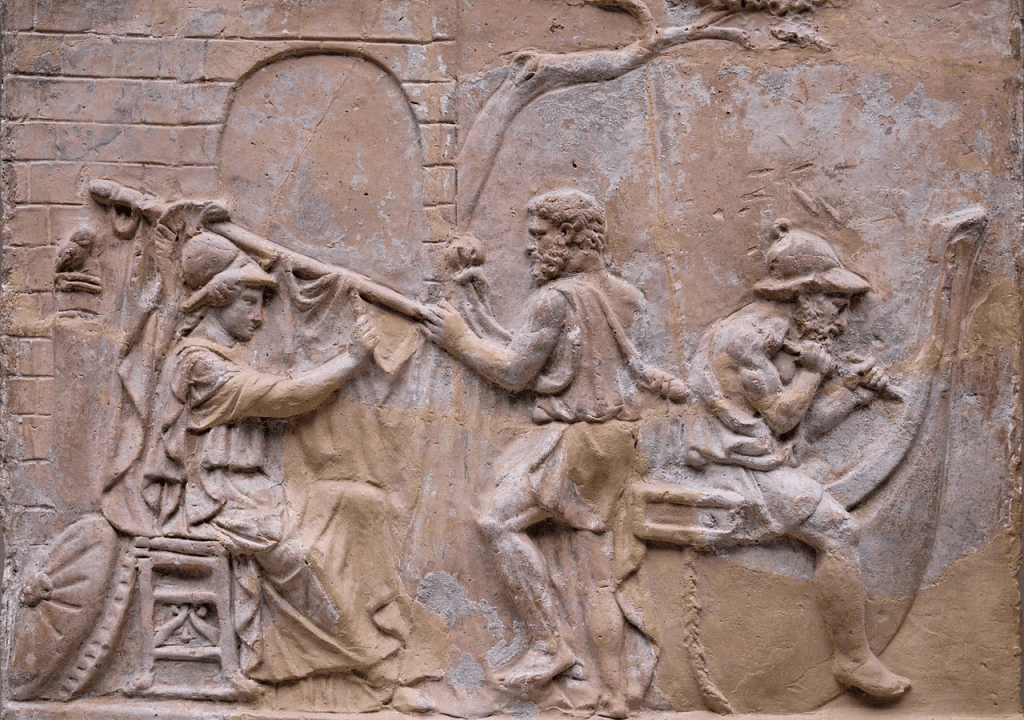

Ecphrasis (Greek ἔκφρασις), originally meaning digression, has become the technical term for an extended description of a work of art, embedded in a narrative context within an epic poem or some other type of work. The archetypal example is of course the Shield of Achilles in Book 18 of the Iliad. In that book Thetis watches the divine artificer Hephaestus bringing the work into being. The shield presents a vision of the cosmos, including the heavenly bodies and (in much more detail) the human world at peace and at war, the world of festivities, farming, song and dance, much of which is remote from the main plot of the epic (even the scenes representing war are small-scale conflicts). This is the world which Achilles has to leave behind as he accepts his destiny and commits himself once more to the battlefield.

The shield of Achilles was the model for many later descriptive passages, most obviously the shield of Aeneas in Book 8 of Virgil’s Aeneid. Of course, the work of art could take a different form: other examples include the images on Jason’s cloak in Apollonius, the lavishly designed wooden cup offered as a gift in Theocritus’ first Idyll, or more light-heartedly the beach-bag carried by princess Europa on her way to the seaside (as in Moschus’ Europa): even this frivolous object has been made by Hephaestus, and rather impractically is said to be made of gold!

When an ecphrasis is present, interpreters often seek to define the relation between the scenes portrayed and the themes of the work as a whole. In some cases this is fairly straightforward. In Moschus’ poem Europa’s bag shows the story of Io, loved by Zeus and transformed into a cow; forced to journey across the sea to Egypt, she is eventually turned back into human form. This has obvious relevance to Europa’s own story. She too will be a ‘bride’ of Zeus, and the bovine aspect is present in that she is transported across the sea to a different continent by the god in the form of a bull. So the scenes on the bag are ominous, foreshadowing her impending adventures. Other examples are more elusive, though commentators are generally able to draw ingenious connections.

Before turning to my example from Valerius, some further remarks about Virgil. The shield of Aeneas does not stand alone. The scene clearly balances an earlier ecphrasis in Book 1, where the poet describes the images on the doors of Juno’s temple at Carthage. There, at the low point of his fortunes, Aeneas sees a series of images representing the Trojan war and focusing on Trojan defeats or disasters: the deaths of Troilus, Rhesus, Hector are mentioned. He naturally recognises the scenes, and indeed observes himself portrayed among them.

In Book 8, by contrast, the shield made by Vulcan presents a series of Roman successes, episodes from the remote future portrayed by Vulcan with his divine foreknowledge, familiar to Virgil’s audience and to modern readers, but unknown to the hero. In both scenes Aeneas is presented as “marvelling” (1.456 and 494, 8.619 and 730 miratur rerumque ignarus imagine gaudet), but in the first case he admires the images of his past, whereas in the second he simply gazes in wonder and incomprehension.

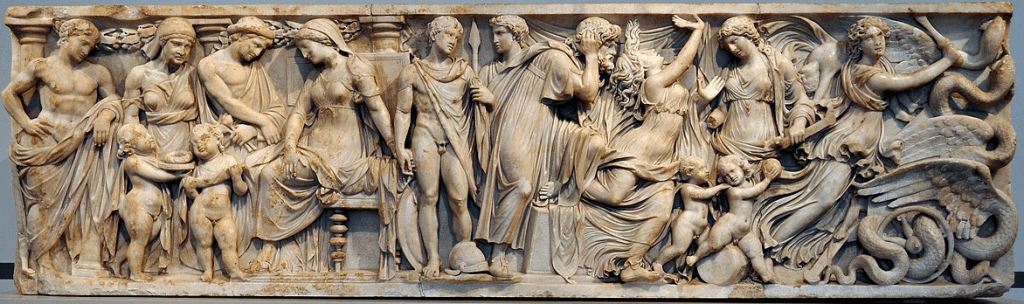

In Book 5 of Valerius’ epic, the Argonauts make landfall at Colchis, and begin to explore the territory. Medea, rising early and catching sight of the new arrivals, encounters Jason and tells her handmaid to guide him and his men to the city of her father Aeetes. The parallel with Book 1 of the Aeneid (and its model in the Odyssey) is obvious. There follows a description of the impressive citadel and temple; here again, we are soon told, the images are the work of Vulcan. (Apollonius does not include an ecphrasis at this point, though he does use the device several times elsewhere in his poem.). Jason is impressed and delighted (laetus) by the portrayal of Atlas, of Apollo in his role as the sun god, and of the Pleiades (we are reminded of how Homer began describing the Shield of Achilles with the heavenly bodies).

But the ecphrasis only begins in earnest at 5.416ff., with the images on the double doors (again recalling Aeneid 1). We are told that they show the origins of the Colchian race and subsequent events of mythological history, including the fall of Phaethon. Then comes the surprise: aurea quin etiam praesaga Mulciber arte / vellera venturosque olim caelarat Achivos (“also Vulcan had engraved with prophetic art the golden fleece and the Achaeans who would one day arrive”)!

A moment later Jason is viewing the construction of the Argo, and himself as commander setting foot on the ship and summoning his followers aboard. This echoes Aeneid 1 where Aeneas recognised himself in the reliefs on Juno’s temple, but those were events years in the past, and there we were explicitly told that accounts of the Trojan war had spread across the world (Dido is well informed about it). Here Jason sees images of events that have only just happened.

The surprises do not stop there. As we read on, Vulcan’s work moves from immediate past to future events:

apparent trepidi per Phasidis ostia Colchi

clamantemque procul linquens regina parentem.

urbs erat hinc contra gemino circumflua ponto,

ludus ubi et cantus taedaeque in nocte iugales

regalique toro laetus gener; ille priorem

deserit: ultrices spectant a culmine Dirae.

At the mouth of the Phasis the agitated Colchians appear, and a princess, leaving far behind her parents’ cries. And on this side there was a city, surrounded by two seas, where revelry and marital song were found, with nuptial torch at night, and a son-in-law rejoicing in his royal marriage. He abandons his former wife; the avenging Furies look on from a high rooftop. (5.440–5)

Medea’s flight with Jason is portrayed here, before it has happened. And a line later we have moved beyond the limits of Valerius’ poem (probably) and Apollonius’ (certainly), into the story of Jason in Corinth, abandoning Medea for a more prestigious Greek princess, as in Euripides’ tragedy Medea. In the next lines we get a further stage of the same plotline: Medea (still unnamed) prepares the deadly gifts for her rival; the princess is burned alive by the poisoned robes; the whole palace is engulfed in fire (this goes beyond what Euripides described). The ecphrasis concludes as follows:

haec tum miracula Colchis

struxerat ignipotens nondum noscentibus ille

quis labor, aligeris aut quae secet anguibus auras

caede madens. odere tamen visusque reflectunt.

Quin idem Minyas operum defixerat horror… (5.451–5)

These marvels in that time the Lord of Fire had forged for the Colchians, though they knew not as yet what trial this was, or who was cutting through the air on winged snakes, dripping with blood. Yet they hated the sight, and turned their eyes away.

And indeed that same dread of the work had pinned the Argonauts to the spot, when…

Apart from the reference to the Colchians themselves, no proper names are used in this passage: Jason, Medea and her rival are unnamed; so is Corinth. Some things are hardly more than hinted at: the infanticide is mentioned only in the closing lines, with the cryptic words caede madens. As in Virgil, the god presents images of a future as yet unknown to the human onlooker; but whereas Aeneas looked at the scenes on the shield with wonder and pleasure, and hoisted it on his shoulder with new confidence, both the Colchians and the Argonauts (the Minyae) are repelled by the scene even though they cannot discern its significance. Miracula (“marvels”) the images may be, but the reaction of the spectators is not wonder but horror.

What Valerius has done, then, is to combine the two linked scenes in the Aeneid. There Book 1 included an ecphrasis of Troy’s past, Book 8 one of Rome’s future. In Valerius past Colchian history and Jason’s earlier voyage are intelligible, but the future flight of Medea, Jason’s betrayal and its horrific consequences are as yet unknown to him – he and Medea have barely met, and although they are plainly attracted to each other, no thoughts of a future together have even crossed their minds. If the Colchians do not recognise their king and princess in the picture, there is no reason for Jason to see a resemblance between the girl he has just met and the image of the daughter fleeing overseas (evidently Vulcan’s miraculous skills do not extend to exact portraiture).

In Moschus’ Europa events were foreshadowed by analogy – the images of one of Zeus’ conquests paves the way for his ravishing of another. In the Aeneid the hero is shown the future which his efforts will make possible, but there is no scene on the shield which will involve himself: the earliest events described are the birth and upbringing of Romulus and Remus. Valerius’ innovative technique means that although his epic, even if complete, would not have reached the end of the tale of Medea, he has provided a glimpse of that ending, including as a final element her departure in a chariot drawn by snakes or dragons (which coincides with the closing scene of Euripides’ Medea).

Valerius has suffered some neglect because of the unfinished state of his work, because he is less dazzlingly imaginative than his contemporary Statius, and because he is unduly addicted to somewhat laborious catalogues and combat scenes. Recently there has been considerably more interest in his poem, and this passage shows that although he had greater predecessors, he is capable of doing something novel and ingenious with his inherited material.

Richard Rutherford was Tutor in Greek and Latin Literature at Christ Church, Oxford, from 1982 until his retirement in 2023. He is the author of a number of books and articles, including commentaries on Homer (Iliad 18 (2019) and Odyssey 19 and 20 (1992)), Classical Literature: A Concise History (2005), and Greek Tragic Style (2012). He continues to read and publish in retirement.

Further Reading

Michael Barich (trans.), Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica (XOXOX, Gambier, OH, 2009): a more contemporary version than the archaic Loeb edition by J.H. Mozley.

Denis Feeney, The Gods in Epic (Oxford UP, 1991): pp.313–37 deal with Valerius Flaccus.

Mark Heerink & Gesine Manuwald (edd.), Brill’s Companion to Valerius Flaccus (Brill, Leiden, 2014). A wide-ranging collection of essays.