W.H.D. Rouse

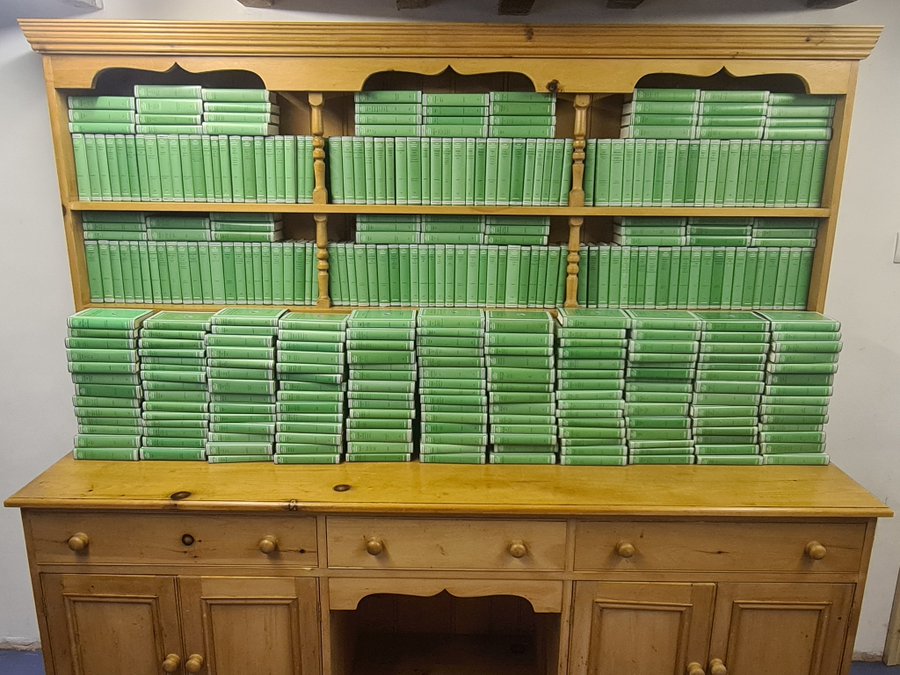

The essay that follows was written by the Classicist and educational pioneer W.H.D. Rouse (1863–1950) in 1911, and was commissioned for the newly-founded Loeb Classical Library Series, of which he was an editor. These iconic volumes, issued in green cloth for Greek and red cloth for Latin literature, and with a facing English translation of an immense range of Greco-Roman authors, were designed to make Classical literature accessible to a broad audience. Rouse’s pamphlet, separately published alongside the first volumes in 1912, was designed to promote the series indirectly, by promoting the enduring importance of the Classics, the clarity of Greek and Latin, and the empty distractions of the brave new world in an age of increasing uncertainty. The essay was freely available on request to the publishers (Heinemann) for several decades. We are pleased to reprint it here, not least as a striking specimen of the infectious enthusiasm of a true believer.[1]

MACHINES OR MIND?

What is the use of Greek and Latin literature? I have to answer this in a very few pages: therefore I must be dogmatic. But I shall say nothing that I am not prepared to prove, in detail, against any challenge: in most cases I have the proof already written.

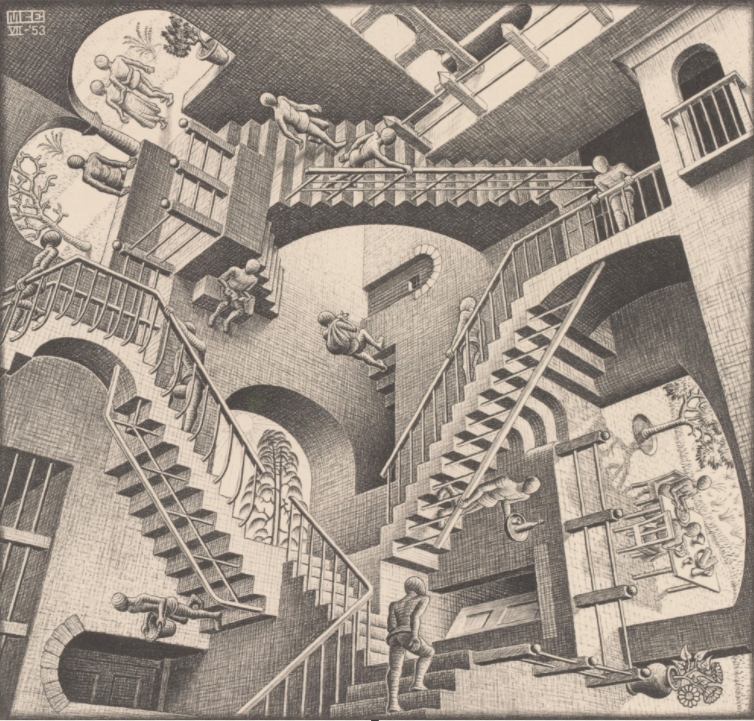

First I will ask another question: What is the use of machines? The world is full of machines: railways, telegraphs, telephones, motors, flying-machines, talking-machines, adding-machines, typewriters—no end to them. Why are they made? To save time, space, trouble, money. They are often a nuisance to everybody around, they spoil one’s eyes and ears, offend the senses, make life dangerous; worst of all, the better the machine, the less it uses our intelligence. It is quite possible to argue that they do more harm than good: but suppose they are all good, suppose time, space, money, labor is saved, what then?

The question then comes, How am I to use the time, space, money, labor which has been saved? In making more machines? In sloth, eating, drinking, self-indulgence? In quarrelling with my neighbor, and destroying what I cannot understand?

Here is the question which the world has not faced. So much time has been saved, that thousands of people who used to be working all day now have leisure; and they do not know what to do with it. They are often ignorant, violent, intolerant, and they are so many, that the few wiser who ought to guide them are forced to follow. To what end?

He who can show the world how to use its leisure will be a greater benefactor than Watt, Stephenson, Edison, Wright, or any maker of machines. Civilisation lies in the mind and soul, not in machines. The most highly civilised nation of history was Athens in the years 500 to 400 BC, and they hardly knew what a machine was.

We offer you the classical literatures to employ your leisure. They will not earn you one shilling of money, or build one electric tram; but they will fill your mind with wisdom and beauty. There is the use of Latin and Greek literature.

Your mind cannot live without them. All the great intellectual impulses begin in Greece; the modern world only grows crops from the Greek seed. All the great political ideas come from Greece or Rome: the very notions of law and empire are theirs, and without them a modern empire is only an organised horde, like Gengis Khan’s, or an organised shop, a gigantic trust, greed, blood, and iron. All poetry and philosophy has its roots there. Your very books and newspapers are full of allusions to Greece and Rome: cut them out, and it would be like a world without the electric force.

I will now take these topics in more detail, and show, first, what you can get from the translations, and then what you can get from the texts.

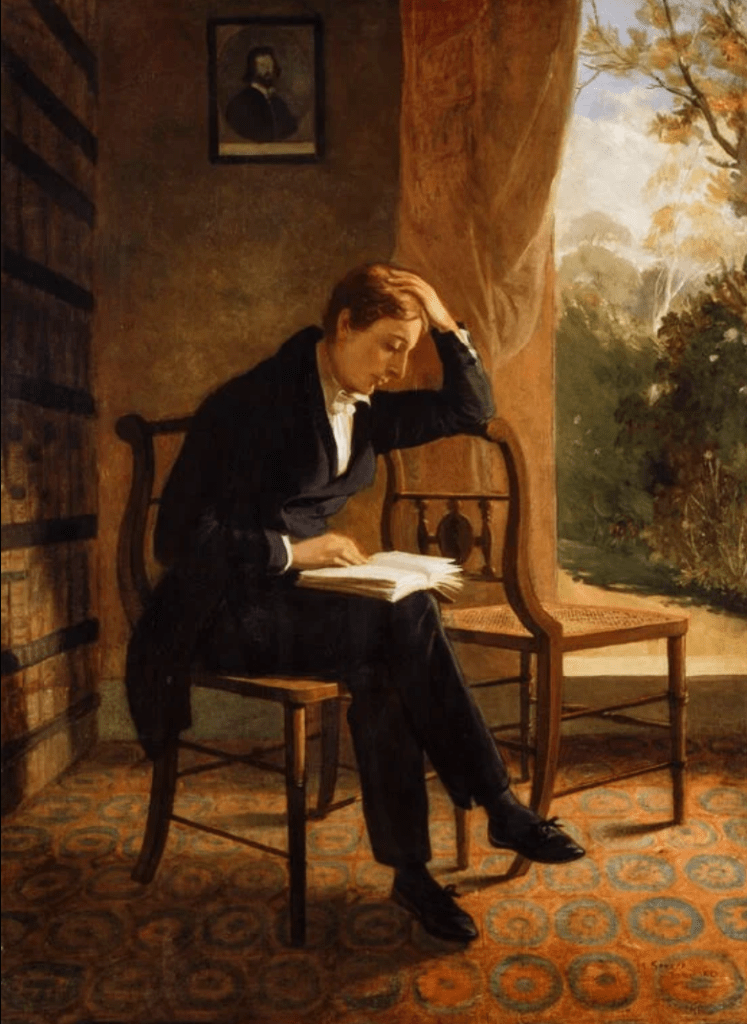

Poetry cannot make a machine, but it is the food of the imagination: it expresses the highest part of man, his eternal hopes and fears, his most intimate feelings, his speculations on the universe, and on his own great end. There is one epic poet, Homer, the Greek. Other Greeks imitated Homer, but they never came near him; Vergil wrote what he called an epic, and so did Milton, but they are not epics. The epic poet depicts a real world in action: there it is, as clear as if we saw it with our eyes; clearer indeed, for the art of the poet lies in that he can, by selection, bring his world within focus for our eyes, which we could not do for ourselves. What a supreme achievement Homer’s was, we can see, if we compare Thomas Hardy’s effort to bring Napoleon’s world before our eyes. He has failed: Homer succeeded, no one else has ever succeeded; and Homer stands, therefore, unrivalled at the head of the world’s poets.

Vergil and Milton used the epic form for an abstract subject; Vergil depicted the rise of empire, Milton the ways of God with man, grand achievements, too, but not epic. They were philosophic poets both, Vergil also a romantic poet: Homer is the only epic poet. And what a world he depicts for us! The fresh young manhood of the only intellectual race of our planet; when men had the simplicity of childhood and the mind of manhood, so that their every act and word lays bare the springs of human conduct. With us, these things are overlaid with pretence, polish, reserve, what you will, like our complex coats and skirts, ugly and disguising: then the man showed his naked body without shame, and his mind without reserve. And we have all the range of emotion, from high pride to baseness and cowardice, tender love, generous pity, fierce and ruthless hate, painted in scenes that are like life. Is it of no use to see this world put before us? Can we not learn thus to know ourselves?

And to know ourselves becomes possible in other directions, when we read the drama. Shakespeare is the supreme dramatist, take him as a whole: but he never surpassed, though he may have equalled, the four great Athenians in their several kinds—Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes. And they deal with themes which we do not always find in Shakespeare. We could not do without Shakespeare; but neither can we do without these four. Aeschylus, the loftiest intellect of all who ever thought on this earth, grappled like Isaiah with the great problems of divine justice and mercy, sin and its punishment. His Prometheus is the sublime figure of a god suffering for men, conceived in his mind five hundred years before Christ was born. The Oresteian trilogy shows the sin of man, working from generation to generation, until justice and mercy are reconciled in a mysterious act of faith.

Sophocles, the perfect artist, who never wastes a word, shows his profound thought through language clear as the waters of an Aegean gulf. In his work we see the conflict of human law and personal duty; of an innocent man with the seeming blind forces of destiny, and the reflected glow of future glory which shines at his translation. We see pictures of the perfect wife, the proud man humbled to the dust, the weak man driven to deeds of awful terror, the generous youth trying to persuade himself that the end justifies the means.

Euripides, the sceptic, turns the cold glittering light of his mind upon the shams of society and religion, and they blow away, leaving humanity as it is in all its grandeur and all its baseness. To study these men is to learn self-knowledge, and to tremble at it. No modern poet can fill their place, if only because our social setting is so different: in a setting so unlike ours we see the real issues as they are, unwarped by prejudice.

Aristophanes again, with his irrepressible bubbling fun, his political shrewdness and good sense, is charming even to those who cannot feel the inimitable beauty of his lyrics. Here again we have problems that are important to us. His Parliament of Women came 2,300 years before the suffragettes; his pictures of the new democracy and utilitarian education might almost have been made to-day; in his City in the Clouds the humbugs of our civilisation reappear. Can you say Aristophanes is dead, when only recently a faint shadow of him had a great success on the Parisian stage, or Sophocles, who held Berlin all through the season and London as long as he was played?

I have no space to speak of the other sorts of poetry: the didactic, the lyric, the epigram, the comedy of manners; but here again Greece comes first, other nations a long way after. And in Pindar she has a figure whose grandeur has never been approached: like Homer he stands alone, he has neither rival nor second.

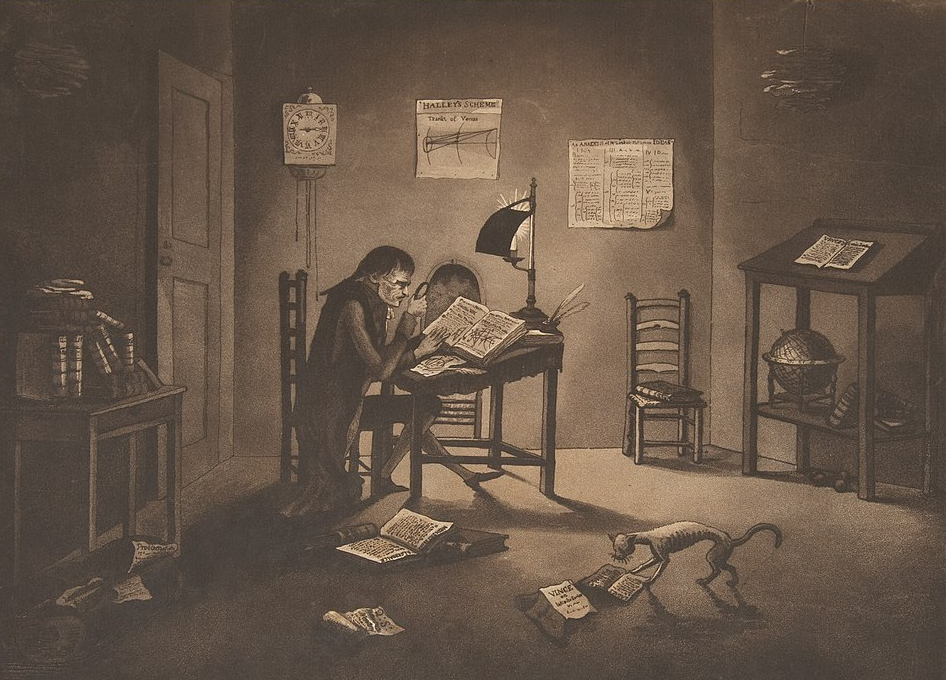

Take philosophy again. There is only one philosopher, Plato, who has created a complete system that takes in all human life and destiny; and he was also the most perfect literary artist in prose of all that ever wrote. He, withal, has a new world to show us, before our eyes, as clear as Homer’s, if not so wide: the cultivated society of Athens at her best, a group of lifelike figures around the noblest soul of antiquity, Socrates. Add to him Aristotle, the creator of scientific method, who took all knowledge for his province, and dominated the thought of Europe for two thousand years: where is his like to be found? Those who now affect to despise him owe to him their intellectual life in this department.

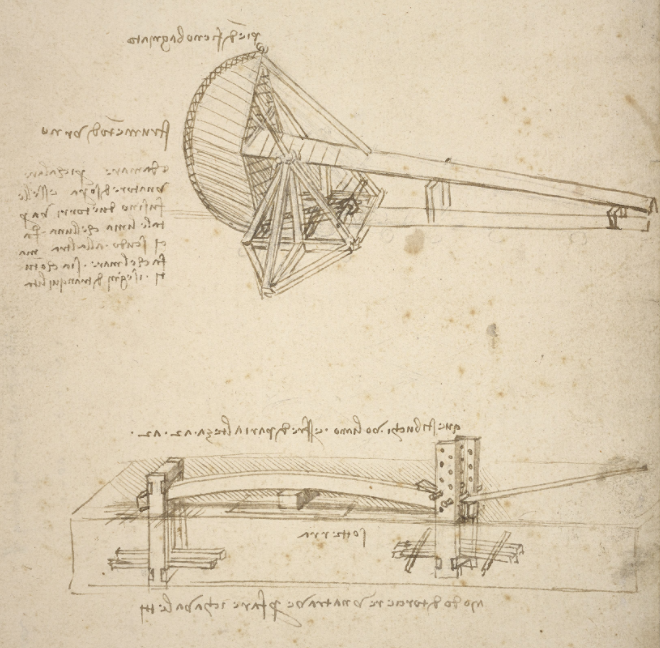

I mention also those natural philosophers who invented the atomic theory, who laid the foundation of discovery in physics and chemistry, in mathematics and engineering. They even invented machines! Who first made a screw? Who first made the lock in a river? Who studied the lever? Who solved problems without algebra and without arithmetical figures, which would be difficult with the aid of these? Who founded scientific medicine, and knew many things that have been quoted as the discoveries of the modern world? Who knew the courses of the Pleiades and mapped out the stars? Who found out that the earth is round? The answers to all these questions are Greek names: and one great Latin name, Lucretius, is that of the only man who ever made science and poetry meet. Compare Lucretius with Erasmus Darwin’s Loves of the Plants, and say then whether the ancient or the modern world has the advantage.

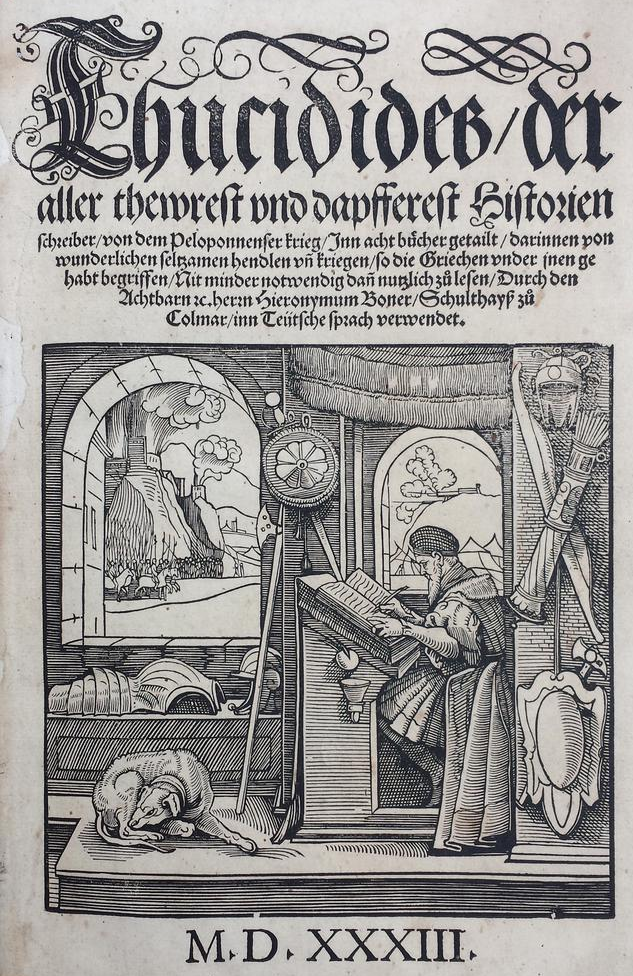

Turn now to history; and see the first anthropologist in Herodotus, the first scientific historian in Thucydides. Like a true Greek, neither of them is content with being a historian: both are inimitable men of letters. There never was such a man for telling good stories as Herodotus. Here is something to fill your leisure in lighter moods; but he has plenty to tell that is of solid value, history even, the history of the most momentous war of antiquity, which gave us Greece and might have quenched that light. Thucydides with his sombre spirit, his severe impersonality not only gives the most moving description of the horrors of war, but lays bare the cynical baseness of the politician’s mind. For political science, Thucydides is a master. Perhaps even the Humanitarian League may find something in him to use in their cause. As to his power, Macaulay thinks the Retreat from Syracuse the first piece of historical writing in the world. “It is the ‘ne plus ultra’ of human art,” he says.

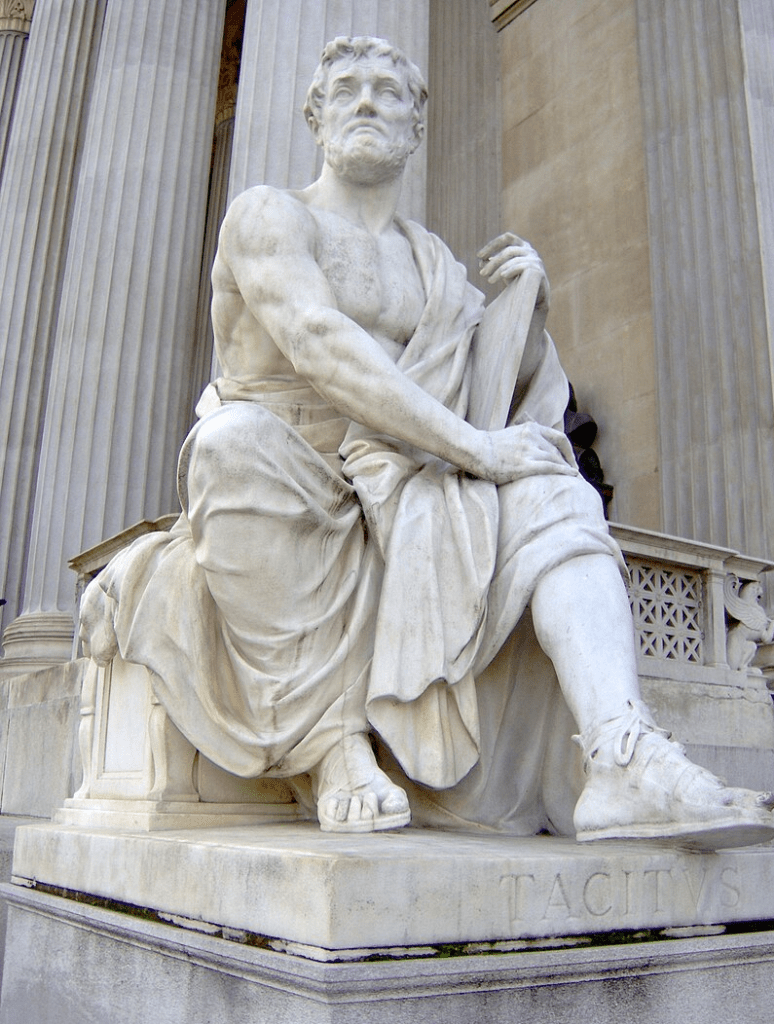

Here the Romans too have their masterpieces: Caesar, whose plain tale has the grandeur of his own genius; Livy, the master of description, whose style is so taking that the moderns think he cannot be scientific, as he tells the story of Rome in epic fashion; Tacitus, the master of epigram and innuendo, who shows what statecraft looks like to a man when the iron has entered into his soul. All these historians are able not only to instruct but to delight.

Modern historians affect a different style, unluckily for us. Perhaps they can no better.

Among the orators are the two admitted of all to be supreme—Demosthenes and Cicero. Both are full of political wisdom, both ardent patriots; both, out of office, lost, not their seats, but their lives for their patriotism. Both in subject are singularly modern. The arguments used to awaken Athens to the designs of Philip might be used today to follow the King’s call, “Wake up, England!” If the modern politician can learn anything, he may learn from Cicero how national credit is affected by rash legislation, and how it is wise to deal with the land. The second speech against Rullus[2] might be addressed, with a few changes, to the House of Commons. Many of the forensic speeches are models of eloquence: Brougham[3] is not the only great speaker who has found practical benefit in their study. There are, too, many other orators, who all have their interest, and most are very attractive to read.

Cicero has two other sides. As a philosopher he only reflects the Greeks, although he is our source of knowledge for much of theirs that has perished. But as a letter writer he is unique. Never was such a faithful picture of the varying moods of a great mind: a very human and moving story they tell.

Vergil and Horace are also without rivals. The imperial idea in Vergil we have already noticed, but there is more. His Aeneas is worthy of the psychologist’s attention. This complex character has been put into the shade by the other beauties of the Aeneid, but it is there as clearly as if George Eliot had analysed it, in about one-fiftieth of the space. Horace, every man’s poet, says a thousand good things with nice perfection, and appeals to the whole intelligent world: he has also invented a new kind of lyric, without the spontaneous fire of the Greek, but unequalled in majesty.

I have only touched on the greatest names; but there are a hundred others of less mark, all, or nearly all, good and useful in their own ways. Of the classical age, while some of the best has perished, very little remains that is not good. Our series will include the writers of later date, a thousand years of them, which, as they are less perfect in their original form, are therefore easier to translate. With the greatest of all, form and matter are so closely bound up that fully half their virtue goes in translation: later authors are good chiefly for what they tell us. It would be worth while learning Latin and Greek even if only the second-rate authors had been left; but our readers will not need to go to that trouble, when our task is done. It is not easy even to indicate these writers by classes.

Take first the Greeks. We have few poets now, though there are some; but we have many historians, from Polybius and Strabo to the Byzantines. To name only one: here is Procopius with his gossip about Justinian’s Court, his Persian, Gothic and Vandal Wars, the buildings of the great emperor. Here are geographers, philosophers, rhetoricians, grammarians, and many a picture of life is found in them. Dion Chrysostom’s Hunter gives a vivid description of life in the hills, the novel of Daphnis and Chloe the life on a farm; other novelists give the town life.

Two great names stand out from this throng, Plutarch and Lucian. Plutarch’s Lives of Noble Men have fed the imagination of boyhood ever since; his other work, a collection of essays on all sorts of subjects, is less known but full of matter: criticism, history, education, mythology, folk-lore, all sorts of things. As for Lucian, the most brilliant of satirists, as witty as Voltaire but not morbid, as biting as Swift but always sane, he is an everlasting fountain of delight; he charms every reader, as well the most subtle as the most simple: schoolboy and artisan, scholar and critic, all are charmed by his magic.

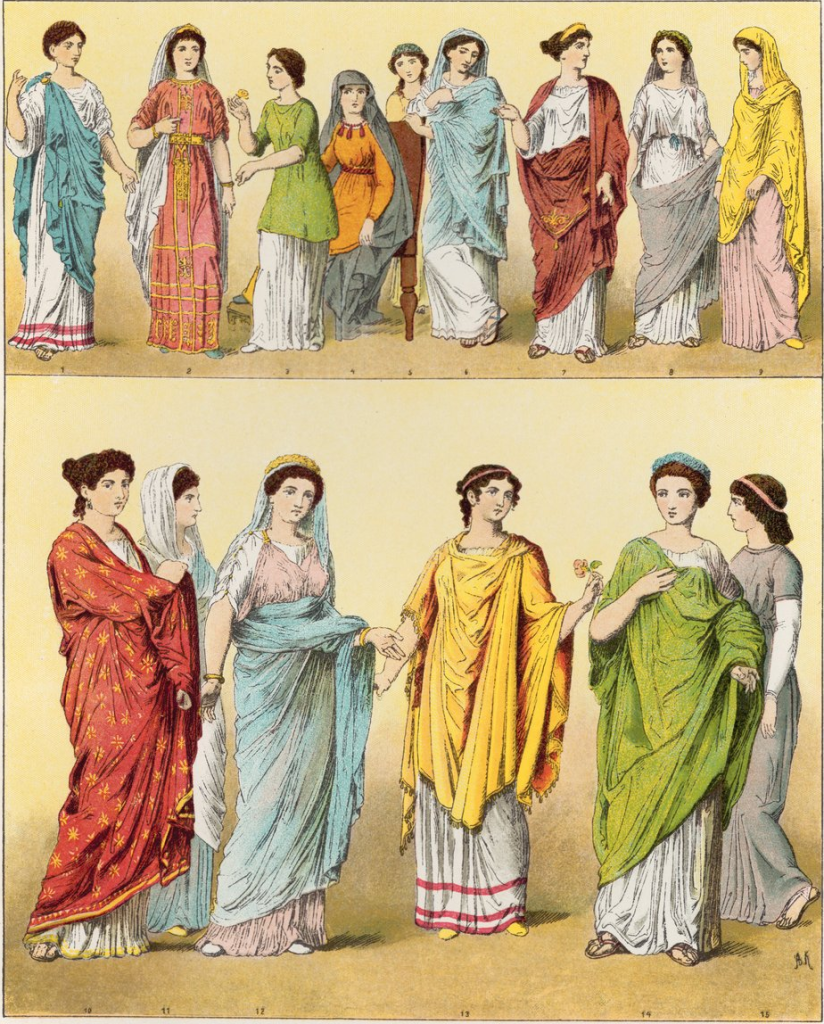

Nor should we forget the long line of the fathers of the Church: they give us, not sermons only or the dry bones of theological controversy, but human life again. The mythologist will often find in them careful descriptions of the superstitions that they denounced; the social student will find many a hint for his study; the lady of fashion will find the women’s dress.

Much the same may be said of the Latins. Here we have a new subject of importance, namely law, and most of the other subjects are represented. There are many poets, although they are less to our taste, yet even quite late we find sparks of genius, as in the Pervigilium Veneris. Or again, we have such works as Pliny’s Natural History, a library of entertaining facts; Suetonius, with his gossip of the Caesars; Apuleius, with his tales of witchcraft and magic; Quintilian, the first scientific schoolmaster, source of most of the educational ideas of the Renaissance, and an accomplished rhetorician; Arnobius, the mythologist; Lactantius, the purist in style, most polished of theologians; Symmachus, with his villas and his country life; Cassiodorus, whose letters give a vivid picture of the time of Theodoric; Augustine; Bede, and a score of others. The student of religious thought will find most fascinating the dialogue of Minucius Felix, from which he will see how the educated man when confronted with Christianity could reconcile the old Roman religion with his conscience.

Besides these there are the inscriptions and papyri, which will be brought for the first time within reach of the many. These documents are not only important as sources for historical deductions; they portray the life of the past, within certain limits, as nothing else can do. History and social custom are seen in the making; we read of building and farming, of business and of war, life and death, religion and piety; here are the very bankers’ accounts, the private letters of Tom Nokes and John Styles, the very scribblings of schoolboys on the wall, advertisements, and election placards.

The translations that we are to publish will be partly new, partly old. Some there are that are among the glories of English literature, such as Adlington’s Apuleius, and especially the works of Holland, “translator-general of his age”, as Fuller calls him. But the greater part will be new. It is intended that these shall be worth reading for their own sakes—English translations, in fact, not keys to the Classics. The founder of this series hopes that the treasures of Latin and Greek literature may be brought within the reach of all who can read English. Those also who learnt Latin and Greek in their youth, if the weeds have sprung up and choked them, may perhaps be encouraged to revive their knowledge and to extend it. Best of all it would be if those who have not learnt any should be drawn to learn now: “Cras amet, qui numquam amavit: quique amavit, cras amet“.[4]

But why should they? Because the best translation can give no more than the dry bones. If a translation is more than that, it is so by virtue of something that is not in the original. It may to some degree reproduce in English the effect that the original has in Greek or Latin; but it will do so by changing the associations of this original and putting in new ones.

Only the original can give, not only the bare sense, but all the suggestions and associations which the author meant to call up; only that can give the thoughts in their order, the very music and cadences of sound. The text, and the text alone, is the real thing. If readers enjoy a translation—and they will—then the text they will enjoy a thousand times more.

The very languages give what English does not give. Modern English is full of roundabouts, of metaphors without meaning, verbiage, shams: Greek and Latin are plain, direct, true. English can be these things, but it is not. The English language is largely dead: Greek and Latin are living languages.

I do not now speak of the language of scientific books. That, indeed, is a horror such as never was on sea or land. Dip into any book in any branch of science and your hair will stand on end, if you have any feeling for words at all. I look into the leading literary journal and see this: “With regard to the corollary to Dr. Gaskell’s theory, which necessitates the assumption that what was hypoblast in the anthropod has become epiblast in the vertebrate, and vice versa, Professor Willey says that the integrity of the gut throughout the tripoblastic animals cannot be assailed without invalidating the continuity of the archenteric cavity throughout the metazoa; but this is to strike at the root of the entire fabric of comparative morphology.” How unhappy the few English words look in this chaos, “rari nantes in gurgite vasto.”[5] And what is the root of a fabric?

But this disease is as common, though not so bad, everywhere. One talks of a one-sided “point of view”: how many sides has a point? Another says that the “line of demarcation here assumes shadowy dimensions”: what are the dimensions of a line? What is the shadow of a dimension? I look at my Times leader and read: “The value of such a statement as the French Minister for Foreign Affairs made last week in the Chamber of Deputies lies very largely in the effect which it produces.” What other value can it have than the effect which it produces? These sentences are all dead: they either wrap up a simple sense in meaningless words, or they seem to have a meaning when they have none. Take, again, a natural seeming sentence: “I cannot explain his absence.” Here we have a dead metaphor, explain, and an abstraction made concrete, absence; but neither metaphor nor concrete nonentity calls up any image at all to the mind’s eye. Greek and Latin, on the other hand, go straight to the point: Οὐκ οἶδα διὰ τί ἄπεστιν, “nescio quare absit”.[6]

As a general rule, the more abstract nouns, the more darkness and doubt: the more verbs, the more light there is. I do not say that English cannot go to the point: it can, but it does not. Which, then, is the dead language?

Greek is not only a living language: it is noble. There is no vulgarity in classical Greek and no affectation: in its good days it had no dialect for the vile and base to smirch our ears with, no preciosity, nothing without sense; and every hint or phase of meaning, however faint and delicate, can be expressed in it. What we put in a tone, a shrug, a gesture, the Greek can put into words. Latin, again, is the language of reason. Greek can reason as well, indeed, or better; but it is more easy and natural as a rule. Latin is usually strict, logical, periodic. Thus these languages help to cure that slovenliness of thought which is a mark of the modern world. This world of machines which bows down to the Dagon of Science, falsely so called, never had an equal for fallacies: there never was a world, except perhaps Rome in the fourth century and Byzantium in its last age, that cared less for truth in speech and in thought.

And the languages learnt, we can get close to our Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Plato, Vergil, Caesar: see their thoughts as they sprang and grew, catch their allusions in a flash, hear the sweet and noble sounds which they uttered, feel at one with them in the movements of their minds. We catch their enthusiasm and their love of truth, their insatiable curiosity, their spirit of reason-the Greek spirit. We get free from our modern predispositions and see things as they are: away goes the clammy sentimentality of the modern world, its pharisaism, its cowardice: we see facts before we know it, and we have to face them—a most wholesome and exhilarating discipline, like a cold shower-bath on a winter’s morning.

A grown man, a trained mind, can learn Greek in three months; if he has known it before, in less. And what a world that will open to him!

After this, I say no more. I could find something to add on the use of Latin or Greek for professional men. How a botanist can do without passes my comprehension: and as for modern languages, do but learn Latin, and it is easy to read Italian, French, Spanish, or Portuguese. But these are mere accidents: I am concerned with the right use of leisure. With these literatures to help us, we can forget machines for a while; we can even forgive those who invented them.

Notes

| ⇧1 | We have inserted a number of paragraph breaks, as well as illustrations. The original can be read here. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | More commonly known as De Lege Agraria (On the Agrarian Law). |

| ⇧3 | Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux (1778–1868). |

| ⇧4 | A quotation from the Pervigilium Amoris: “Let he who has never loved love tomorrow, and he who has loved, love tomorrow.” |

| ⇧5 | “Swimming scattered in the vast abyss,” a quotation from Virgil’s Aeneid (1.118) about the shipwrecked Aeneas and his men. |

| ⇧6 | Both phrases mean, “I don’t know why he is absent.” |