Thomas A. Montgomery †

The Ancient Greek lyric poetess Sappho (c.620–c.570 BC) is an intriguing character. She has left some of the most heart-stoppingly beautiful poetry and some of the oldest descriptions of the pains of love. These are visceral and intensely personal accounts of emotions and desires from a woman about whom we know so little and who is not easily understood.

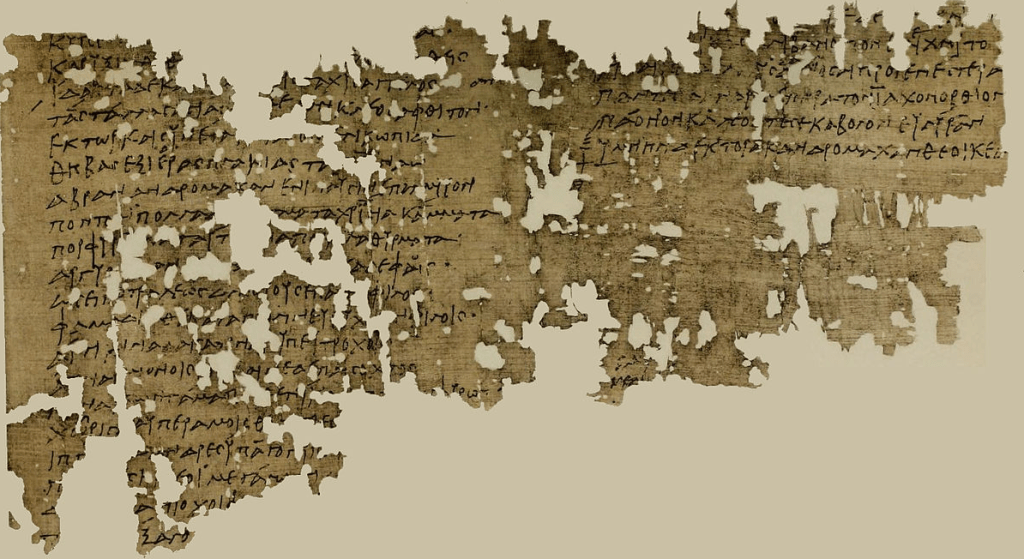

Part of the problem is that very little of her work survives. What we have are ‘fragments’. This means a) quotations of Sappho in other ancient works, whose texts survived to be copied by mediaeval copyists and later printed; and b) scraps of ancient papyrus rolls, typically from several centuries later than Sappho herself, which have been preserved especially in Egypt, where burial in dry sand allows organic materials to survive much longer. Reading her poems thus presents a very real challenge, when all we have are broken pieces.

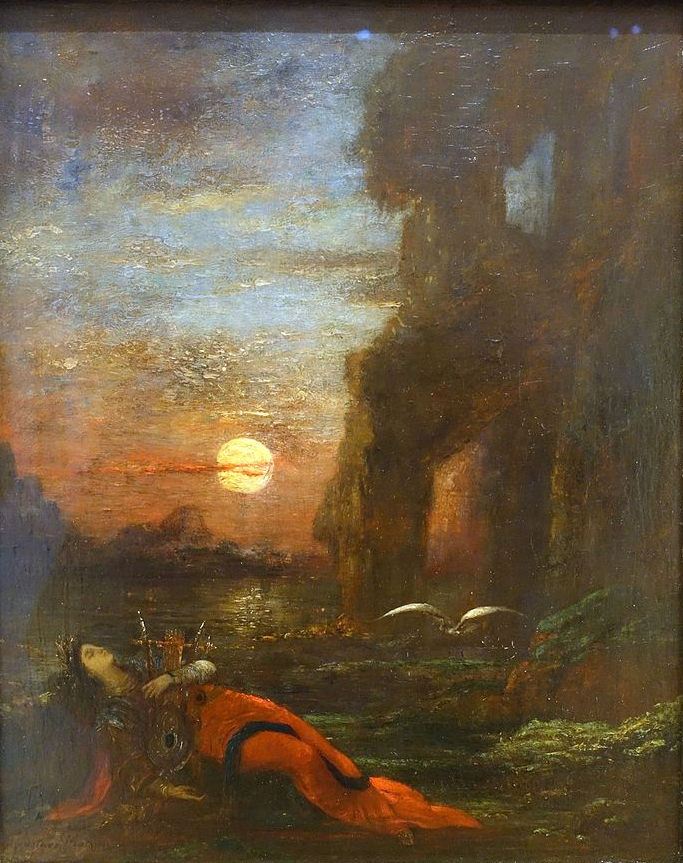

The poems themselves present a highly personal portrait of their author. Yet here we should remember that Sappho is speaking not just for herself, but as the character, or persona, ‘Sappho’, just as the Dante of the Divine Comedy is both the historical poet and a character within his own creation. Some stories told about her in later sources are probably fictions, inspired by her poems. These include the notion that she had a school of aristocratic young girls on Lesbos, or that she killed herself out of love for a ferryman called Phaon by leaping from a cliff.

What we can say about Sappho for sure is that she lived around the end of the 7th century BC on the Greek island of Lesbos. Her family may have come from the city of Mytilene, the island’s chief port, on the southeast coast facing Anatolia across the intervening strait and one of several communities on the island. At about this time the polis was affected by a power struggle between the faction of the poet Alcaeus and the tyrant Pittacus. However, none of this political context is evident in the surviving fragments. Instead, we hear of friends, lovers and family.

The 5th-century historian Herodotus, for example, knew of her brother Charaxus who unwisely bought a courtesan called Rhodopis on a trading voyage to Egypt (Histories 2.134–5). In 2014, papyrus fragments of Sappho’s poem that had served as Herodotus’ source were published – a striking example of the ongoing progress in recovering lost works of literature that have not been read for hundreds of years.

Let us now look in detail at another such fragmentary poem, one of the most evocative, which illustrates many of the problems of reading partially preserved texts. Some eighty years ago papyri were discovered in Egypt containing three sections of Sappho’s poetry, two of them (Fragments 94 and 96) of substantial length. These both relate to the unwilling departure from Lesbos of young Atthis, a favourite friend of the poet. Of the third, Fragment 95, only scattered fragments remain; one of them seems to invoke a death wish as also expressed in Fragment 94. I present the Greek text below and the translation of Sir Denys Page.

Fragment 94

Honestly I wish I were dead. Weeping she left me

With many tears, and said “Oh what unhappiness is ours;

Sappho, I vow, against my will I leave you.”

And this answer I made to her: “Go, and fare well,

and remember me; you know how we cared for you.

If not, yet I would remind you… of our past happiness.

Many wreaths of violets and roses and… you put around

you at my side,

And many woven garlands, fashioned of flowers,… round

your soft neck,

And… with perfume of flowers, fit for a queen, you anointed…

And on soft beds… you would satisfy your longing…

And no… holy, no… was there, from which we were away,

No grove…

Fragment 96

[She honoured] you like a goddess manifest, and in your song

she delighted most of all;

But now she is pre-eminent among ladies of Lydia,

like the rosy-fingered moon after sunset,

Surpassing all the stars; its light extends over the salty sea

and the fields of flowers;

And the dew is spread abroad in beauty, and roses bloom,

and tender chervil and flowery melilot;

To and fro wandering, she remembers gentle Atthis with yearning;

surely her tender heart is heavy.

Many readers have supposed that Fragment 96 tells of the grief of a third person over the loss of Atthis. This girl remains unnamed; she is referred to simply as “you” in the poem’s first surviving lines, and again toward the end. To Atthis this nameless person was like a goddess, her singing most admired. At the end of the fragment she reappears alone, lamenting the departure of her friend.

But there is a problem. Here we are to imagine that Sappho disregards her own affection for Atthis and recognizes the unnamed other as the girl’s favorite singer – presumably overlooking her own pre-eminence as singer-poet. But in the other fragment (F94) it is forcefully declared and Sappho is herself the lover. The solution, I suggest, is to remove the imagined third person, in order for these anomalies to be eliminated and the poem’s structure restored.

The focus should be on F96, with F94 taken as essential context.

F94 is marked by a profusion of personal pronouns: fifteen in the first six lines of the English version. The original depends on verb endings and on context for twelve of them. Still, this frequency of personal references is significant when we turn to F96 and see it as a reflection directed inward. In addressing the second person “you”, the poet speaks to herself. The first result of this device is perhaps to avoid the poor taste of “in my song she delighted most”, but then it does much more. She presents herself as both observer and observed, at once sympathetic and distressed, realistically comprehending her painful situation even as she grieves.

Self-address reappears in the last lines, in the verbs ζαφοίταισα (zaphoitaisa), “wandering”, and ἐπιμνάσθεισα (epimnastheisa), “missing, yearning”. If the first of these is read simply as a second-person present-tense form (ending in sigma, and not supposing the elision of the final alpha), i.e. zaphoitais, “you wander”, this make good sense as the poet addresses herself. Then “her tender heart” becomes “your tender heart”. The possessive form is a product of translation, not expressed in the original.

Page recognized the tense of the verb and expressed great frustration because, having accepted the poem’s alleged third-person reference, he could not fit the pieces together: “This we have seen to be contrary to tradition, analogy, and practice as far as we know.” Still respecting his version, I propose this reading: “To and fro you wander, remembering gentle Atthis with yearning; surely your tender heart is heavy.”

The authorial device of addressing oneself may not occur elsewhere in the writings of Sappho, although a few fragments are possible examples: “I don’t know what to do. / I think yes‒and then no.” (F51, Barnstone’s translation). Self-address is not rare in modern literature, or indeed in everyday experience. If we see the first two surviving lines of F96 as directed by Sappho to herself, the language is direct.

Atthis honored the poet, taking pleasure in her singing. Conflicts among personages disappear: there is just one person in this poem, or two if we wish to include the absent Atthis. The poet is present at first, then the power of nature takes over, beginning with a mental image of the girl in Sardis. Again, in the last lines, Sappho looks inward.

Note also the physical environment, which would have been familiar to her listeners, but can easily escape the attention of a modern reader who focuses on the written word. From Mytilene the moon would appear to rise from behind the coastal hills of the mainland. Atthis had been sent to live in Sardis, a Lydian city on a plain beyond those hills some forty miles distant. For a casual observer of the time, it would be easy to associate the moonrise with the city ‒ indeed, such a coincidence would be likely to become a part of the local folklore: the splendid Aegean moon was necessarily an important presence to people who on most nights depended on torches for illumination.

Before rising, the moon, which we know is full because it appears just after sundown, would briefly send rays over the hills of the mainland, “rosy-fingered” in what appears as a Homeric cliché. The striking sight is an especially apt reminder of her friend’s youthful beauty. The moon then becomes a dominating presence in the poem, measuring the passing of the night in a world where that was not a function of numbers.

Another point: the customary reading sees the poet pacing as the dew “falls” during the night. But when the narrative resumes it is no longer nighttime, because here the dew is associated with the colors of the rose and small leafy plants: chervil resembles parsley, melilot is a kind of clover. Under moonlight, no matter how bright, all but the palest colors turn to various faintly tinted shades of grey before the human eye. Now the sun rises in the east, around the time of the setting of the moon, and illuminates the scene. Sappho has spent the radiant night alone.

In its present incomplete state, the poem’s source includes “sard” from an initial line, undoubtedly referring to Sardis. Beginning at line 17, a few phrases are legible: “for your fate,” then on line 21, “For us, it is not easy to rival goddesses for beauty of form, but you…,” and beginning on line 26, “Aphrodite poured nectar from a golden….” In the first phrase the form “your” serves to corroborate the second-person reading proposed here.

The other fragments imply a new perspective involving the love goddess. We can only wonder what kind of exchange would have ensued upon her arrival; in another poem (Fragment 1) she had a playful streak. But the surviving poem, read as if complete, is expertly constructed, the poet’s solitude intensified by the overpowering beauty of moonlight and landscape.

Thomas A. Montgomery (1925-2022) earned a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star as a result of his service in the United States Army during the Second World War. He enjoyed a long and distinguished career as a Professor of Spanish at Tulane University in New Orleans, serving as Chairman of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese from 1978 to 1981.

Further Reading

This article makes use of Sir Denys Page’s Sappho and Alcaeus. An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Lesbian Poetry (Oxford UP, 1955). Readers looking for a recent introduction to Sappho and the scholarship concerning her work may wish to consult P.J. Finglass & A. Kelly (edd.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho (Cambridge UP, 2021). Fragments 94 and 96 can be studied via the Digital Sappho project.