Nicholas Swift

Grammatical number usually takes a back seat in language classes. What could be more obvious than the distinction between singular and plural? Yet common sense often breaks down upon closer inspection. In the first place, we must distinguish between grammatical number, which is a formal feature of words, and the underlying plurality which it indicates. Although Greek and Latin mark grammatical number in many parts of speech, it only indicates the plurality of substantives, that is, of nouns, and of words functioning as nouns.

In the Latin phrase bona paterna, which equates to English “inheritance”, the adjective bona is used as a plural noun, which is itself modified by the plural adjective paterna; it is an adjective, however, in the phrase bona verba, “kind words”, where it is plural merely as a formality, because it must agree in that way with the noun, although it does not indicate that the “kindness” is somehow manifold. This is especially clear when unus agrees with plural nouns designating singular things, such as unae litterae, “one epistle”, or una castra, “one military camp,” something which Varro pointed out in his scholarly work De lingua Latina (On the Latin Language):

quare tam unae et uni et una quodammodo singularia sunt quam unus et una et unum; hoc modo mutat, quod altera in singularibus, altera in coniunctis rebus (9.64).

Therefore unae, uni, and una are in a sense as singular as unus, una, and unum; it changes in this way because one set is used of simplex things and the other of complex things.

Latin had collective adjectives for this very purpose, so that binae litterae means “two epistles”, while duae litterae means “two letters of the alphabet”, and likewise bina castra, “two military camps”, but duo castra, “two fortified positions”, and trinae nuptiae, “three weddings”. The Greek word for “one”, εἷς (heis), μία (mia), ἕν (hen), by contrast, had no plural forms, although its negation οὐδ-είς (oudeis), οὐδε-μία (oudemia), οὐδ-έν (ouden), “no one, none,” could be plural when used as a substantive, just like plural none in English: τῶν ἄλλων ἀρετῶν οὐδεμίαι τὴν ἑαυτῶν ἐπιδείκνυνται δύναμιν, “none of the other virtues display their force.”[1]

Verbal plurality

Even in verbs grammatical number encodes information about the plurality of the subject and not about any plurality of action. This is more complicated, however, because the number of participants is relevant to certain types of action.

The action of αἱ γυναῖκες ἐκάθευδον, “the women were sleeping”, can be understood as multiple instances of ἡ γυνὴ ἐκάθευδε, “the woman was sleeping”, but the action of feminae congregabantur, “the women were gathering”, or congregabat feminas, “she was gathering women”, is plural in an essential way, the first requiring a multitude of subjects, the second a multitude of objects. Some languages have formal markers for this kind of verbal plurality, but in Greek and Latin it is a semantic feature of verb roots and adverbial prefixes rather than grammatical number.

In addition to verbal plurality of the participant type, there are various kinds of event plurality, such as repetitive or habitual action. This is a semantic feature of verbs like frequentare, “to visit often”, or φοιτᾶν (phoitān), “to go repeatedly”, but it is often expressed with adverbial modifiers, as in saepe dixi, “I often said”, or ἐθύοντο τρίς (ethuonto tris), “they sacrificed three times”.

Event plurality is also latent in the present stem,[2] which indicates uncompleted action, but can be reinterpreted as repetitive or habitual action in certain contexts. In isolation, for example, τὸ παιδίον ἐθήλαζεν, “she was nursing her baby”, might refer to a single event, but the context of Lysias 1.9 makes it clear that the action is habitual: ἐπειδὴ δὲ τὸ παιδίον ἐγένετο ἡμῖν, ἡ μήτηρ αὐτὸ ἐθήλαζεν, “after our baby was born, its mother was nursing it regularly.” Event plurality could be formalized overtly:

- Greek used the particle ἄν with an imperfect- or aorist-tense verb for repetitive or habitual action: the aorist-tense ἐκέλευσεν (ekeleusen), “he commanded,” for example, becomes ἐκέλευσεν ἄν, “he was in the habit of commanding”. The Ionic dialect of Greek employed an iterative suffix -σκ-, so that alongside the imperfect-tense διέφθειρε (diephtheire), “it was destroying,” we also find διαφθείρεσκε (diaphtheireske), “it was often destroying”.

- Latin employed the prefix re– for repeated action in verbs like repetere, “to repeat”, and replere, “to fill again”, as well as the suffixes –(i)tare, and more rarely –sare, to create words such as habitare, “to possess habitually, to inhabit,” volitare, “to make repetitive flying motions, to flutter,” and frigefractare, which in Plautus seems to refer to a series of quick breaths to cool a burned mouth: os calet tibi, nunc id frigefactas, “your mouth burns, you’re cooling it now.”[3]

Upon closer examination we can distinguish single-event and multiple-event plurality. Unlike the habitual action of multiple-event plurality, a sequence of repetitive actions can constitute a single event. For example, a repetitive form of premere is used in the phrase pressare ubera, “to repeatedly press the teats”, i.e. to milk an animal, where the repetitive motion makes up a higher-order collective action.

Latin seems to formalize this distinction with two repetitive forms of agere, the single-event agitare, “to shake”, and the multiple-event actitare, “to do habitually”. Often, however, the same form can express both types of action, and so the verb φοιτᾶν is used for single-event repetitive motion, such as pacing or stalking, as well as habitual action like φοιτᾶν ἐς διδασκάλου, “to frequent a teacher”.

Majestic and modest plurals

Things are even more complicated with substantives. The commonsense notion of plurality, of numerous discrete entities, is simple enough in countable nouns[4], such as ἵπποι (hippoi), equi, horses, or δένδρα (dendra), arbores, trees. So far so good.

But compare the relationship between ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos), “person”, and ἄνθρωποι (anthrōpoi), “people”, on the one hand, and ἐγώ (egō), “I”, and ἡμεῖς (hēmeis), “we”, on the other. If we imagine a tragic chorus singing ἡμεῖς in unison, then it is indeed virtually the plural of ἐγώ, but spoken by an individual it indicates an associative plurality “myself and others” rather than “multiple copies of myself”.

To complicate matters further, ἡμεῖς and nos sometimes refer to the speaker alone, without any associates, and does nearly mean “myself multiplied”. In these cases, the plural form subsumes the speaker into a fictional collective, used either as a plural of majesty, to inflate the ego, or precisely the opposite, as a plural of modesty to deflate the ego by losing oneself in an imaginary crowd.

This type of inflated plural may also explain the use of θρόνοι (thronoi), “thrones”, and σκῆπτρα (scēptra), “scepters”, to aggrandize a single throne or scepter, as well as curious plural-for-singular uses such as irae, “a terrible anger”, πηλοί (pēloi), “deep mud”, or νύκτες (nuktes), “the dead of night”. On the other hand, in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, when the seer Tiresias is pressed to reveal that the king has unwittingly married his own mother, he says:

λεληθέναι σε φημὶ σὺν τοῖς φιλτάτοις

αἴσχισθ᾽ ὁμιλοῦντ᾽ οὐδ᾽ ὁρᾶν ἵν᾽ εἶ κακοῦ. (366–7)

I say that you are unaware that with those dearest to you

you consort most shamefully and don’t see your evil position.

He alludes to Jocasta, the wife and mother of Oedipus, by diffusing her into the plural φιλτάτοις (philtatois), “those dearest to you”, as an ancient commentator pointed out: εὐσχημόνως ἀπήγγειλε τὸ περὶ τῆς μητρός, “he reports the fact about his mother tactfully.”

Countable nouns and mass nouns

In contrast with countable nouns, uncountable or mass nouns are singular by default. They are often described as unindividuated concepts and substances, like anger, or mud, which, as Varro says, sub mensuram ac pondera potius quam sub numerum succedunt, “are classed under quantity and weight rather than number”.[5] Countable nouns can be counted or otherwise quantified in English with words such as many or fewer, while mass nouns are quantified with words such as much or less.

But conceptual frameworks do not always match the grammatical details. Unlike chickpeas and its Greek equivalent ἐρέβινθοι (erebinthoi), Varro informs us that cicer was never plural in Latin, and while we don’t cook a pot of rices, the Greeks and Romans could speak of ὄρυζαι/oryzae, despite the fact that we interact with these foods in much the same way. The word grape is countable in English, but its equivalent raisin is a mass noun in French, while fruit is a mass noun in English but countable in French.

Moreover, many nouns are treated as both countable and uncountable, such as ψόφος (psophos), “noise”, and coma, “hair”. It is possible to count una coma, “one hair”, duae comae, “two hairs”, and so on, but the singular coma can also refer to a mass of hair, as in Statius’ intonsae sub nube comae, “under a cloud of unshorn hair”.[6] In English you can juggle three grapefruits or offer a guest some grapefruit, and, if you hate delicious things, you can buy fewer cakes or simply try to eat less cake. In addition to simply multiplying countable nouns, singular-plural transformations can recategorize nouns:

- Singular mass nouns frequently become countable in the plural, as with nix, “snow”, but nives, “snowflakes”, and likewise, grandines, “hailstones”, ἅλες (hales), “grains of salt”, and πυροί (pūroi), “wheat berries”.

- Mass nouns can be pluralized to indicate varietals, as with οἶνος (oinos), “wine”, and οἶνοι (oinoi), “types of wine”, standard portions, as with caro, “meat”, and carnes, “pieces of meat”, or other units of experience, such as aes, “bronze”, and aera, “bronze objects”.

- The plural creates concrete instances of abstract nouns, for example, μανίαι (maniai), “attacks of madness”, θάνατοι (thanatoi), “cases of death”, fortitudines, “courageous acts”, or silentia, “silent moments”.

- It can also make proper nouns common, as when Xenophon calls on his fellow soldiers to emulate the discipline and leadership of the slain Clearchus: μυρίους ὄψονται ἀνθ᾽ ἑνὸς Κλεάρχους, “they will see a thousand Clearchuses instead of one”.[7]

These distinctions not only vary between languages but change over time within languages. At one point, attires, courages, informations, musics, and thunders were used as countable nouns in English. It can be difficult to detect this by statistical analysis of literary texts, but in some cases we have the testimony of native speakers. Quintilian complains that people use scala and scopa for the collective plurals scalae, “staircase”, and scopae, “broom”, and hordea and mulsa for the mass singulars hordeum, “barley”, and mulsum, “mead”, which indicates a change among some groups of Latin speakers.[8]

In a passage full of observations on Latin number, Aulus Gellius relates a story in which the pedantic grammarian Fronto teases his friend for using the plural harenae, “sands”.[9] Aristotle famously remarked that plurals contribute to ὄγκος τῆς λέξεως (ongkos tēs lexeōs), “weightiness of style”,[10] and in Augustan poetry harenae may have sounded grand, like the sands of Egypt in English. But Fronto claims that Julius Caesar considered it incorrect, which implies that it was already in common use at that time, and its eventual acceptance by prose writers such as Tacitus (Hist. 5.7), Suetonius (Aug. 80), and even Gellius himself (16.11.7) probably reflects an elevation of vulgar usage rather than a poetic flourish.

Collective nouns

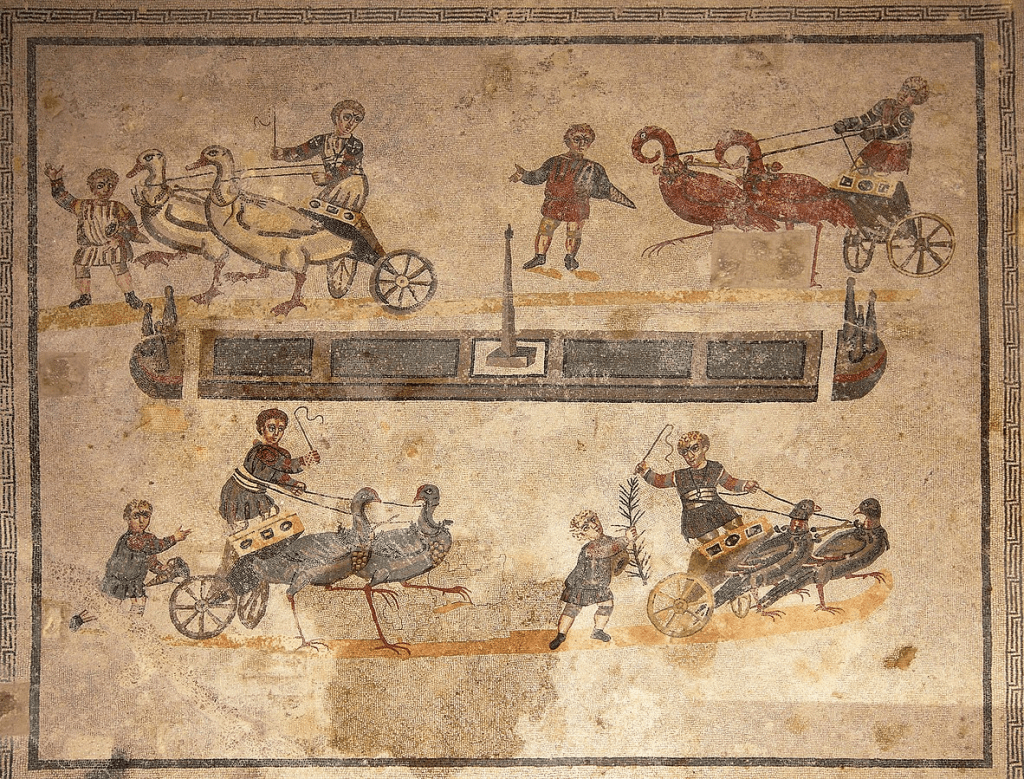

A collective noun is a curious hybrid which recategorizes a plurality of countable things into a unified mass. Many languages have special collective forms; in fact, the neuter plural forms of Greek and Latin seem to have descended from a collective suffix in the parent language. There are traces of it in the alternate neuter plural form κύκλα (kukla), “set of wheels”, beside the masculine κύκλοι (kukloi), “wheels”, and neuter plural μῆρα (mēra), “a pile of thigh meat”, beside masculine μηροί (mēroi), “pieces of thigh meat”, as well as loca and loci, “places”, although no collective sense seems to survive here. This explains why neuter plural subjects take singular verbs in Greek.

Collectivity in Greek and Latin otherwise resides in meaning rather than form. There are generic words like congeries, σωρός (sōros), “heap”, as well as object-specific terms like φάκελος (phakelos), “bundle of wood”, racemus, “cluster of fruit”, and πυρά (pura), “pile of combustible material”.

Animal collectives never became an artform as it did in English, where we commonly talk about a school of fish or a pride of lions, sometimes delight in a murder of crows, and find archaic terms such as a parliament of owls, a route of wolves, a knot of toads, a crash of rhinoceroses, and the grammatically peculiar singular of boars, a pun on the French word sanglier, “wild boar”. But in addition to generic terms like ἀγέλη (agelē), grex, “herd”, there were more specific words, such as σμῆνος (smēnos), “swarm of bees”, or ποίμνη (poimnē), “herd of sheep”, and metaphor was freely employed, as at the end of the Georgics, where a swarm of bees is both nubes, “cloud”, and uva, “cluster (of grapes)”, in the same passage.

The complexity of human organization engendered a richer vocabulary. People were long-standing members of an οἰκία (oikiā), “household”, or a gens, “clan”, but might have brief stints in a chaotic turba, “mob”,or a celebratory κῶμος (kōmos), “band of revellers”, while the χορός (khoros), “chorus”, was a routine artistic and religious manifestation of the community. The Roman exercitus, “army”, marched as an agmen but became an acies when arrayed for battle.

Ancient critics of democracy often used the word δῆμος (dēmos), “common people”, rather like plebs, to distinguish a lower from an upper social class, but its champions understood it more like populus, and in many cases it simply means ἐκκλησία (ekklēsiā), “assembly”, the body of citizens in their official capacity. The massed plebs was always in stark contrast with those individuated patres, whose power was collected in the senatus, which in turn was part of the supercollective senatus populusque Romanus or SPQR.

Singular or plural as you please

Out of these singular collectives a latent plurality could emerge at any time. It is at the root of plebs, as we see in the cognate πληθύς (plēthus), “crowd”, which descends from the same word and is etymologically related; the older form plebes is both singular and plural. We find some collectives with plural forms where the objects are essentially composite, such as scalae, “staircase”, scopae, “broom”, bigae, “two-horse chariot”, comitia, “the Roman assembly”, Ἀθῆναι (Athēnai), “the city of Athens”, δώματα (dōmata), “house”, and τόξα, “bow (and arrows)”. In English we use glasses, pants, tweezers, and scissors for complex objects.

But even a singular form can be the antecedent of a plural relative or the subject of a plural verb in order to highlight its individual members:

- Caesar employs a singular verb in omnisque multitudo sagittariorum se profudit, “the whole band of archers let fly”,[11] where the event is presented as a concerted maneuver, but a plural in cum tanta multitudo lapides ac tela conicerent, “when such a multitude hurl stones and spears”,[12] where the Belgae throw various objects in an assault less organized and professional than a Roman operation.

- In a similar way, in a describing a vote of the Spartan allies, Thucydides uses a plural verb with the collective subject πλῆθος (plēthos), “majority”, in τὸ πλῆθος ἐψηφίσαντο πολεμεῖν, “the majority voted for war”,[13] which emphasizes the diversity of individual opinions. Later, however, Sparta reminds Corinth that it agreed to abide by ὅτι ἂν τὸ πλῆθος τῶν ξυμμάχων ψηφίσηται, “whatever the majority of allies should decide”,[14] where any trace of dissent is rhetorically dissolved in the singular verb.

The conception could even change mid-sentence. In the same breath, Xenophon considers the singular collective τὸ Ἑλληνικόν, “the Greek army”, amassing as a military force with a singular verb and retiring to their separate quarters with a plural verb: πᾶν ὁμοῦ ἐγένετο τὸ Ἑλληνικόν καὶ ἐσκήνησαν αὐτοῦ ἐν πολλαῖς καὶ καλαῖς οἰκίαις καὶ ἐπιτηδείοις δαψιλέσι, “the whole Greek army came together and they set up camp there among many fine homes and abundant provisions”.[15] And we find a characteristic imbalance of style in Thucydides:

Βρασίδας μὲν οὖν καὶ τὸ πλῆθος εὐθὺς ἄνω καὶ ἐπὶ τὰ μετέωρα τῆς πόλεως ἐτράπετο … ὁ δὲ ἄλλος ὅμιλος κατὰ πάντα ὁμοίως ἐσκεδάννυντο. (4.112.3)

Then Brasidas and the majority immediately stormed the city heights… while the remaining band spread out equally in all directions.

Here the collective πλῆθος (plēthos), “majority”, takes a singular verb despite being joined by a second subject Βρασίδας (Brasidās), because their action is singularly focused, while the singular collective ὅμιλος (homilos), “band”, takes a plural verb of dispersing.

Such vacillation illustrates the United States’ evolving conception of itself. It was variously singular and plural for the founders, and Alexander Hamilton even had it both ways in a single sentence of Federalist 15:

Except as to the rule of appointment, the United States has an indefinite discretion to make requisitions for men and money; but they have no authority to raise either, by regulations extending to the individual citizens of America.

The American Classicist Basil Gildersleeve once quipped, “It was a point of grammatical concord that was at the bottom of the Civil War – ‘United States are’, said one, ‘United States is’, said another.”[16] The fundamental issue was slavery, of course, but there is some truth in his exaggeration about the war between the Union and the Confederacy. The plural use dominated in the early 19th century, but diminished in the second half of the century, and by the early years of the next it had been completely eclipsed by the singular.

The Greek dual

In addition to singular and plural, some languages employ dual and trial forms, for precisely two and three things, and even ‘paucal’ forms, for an unspecified few. The parent language of Greek and Latin had a dual number, which survived in Latin only in the fossils duo, “two”, ambo, “both”, and viginti, “twenty”, but was alive, if unwell, in Greek. Mycenaean documents preserve such forms as to-pe-zo (τορπέζω, torpezō), “two tables”, and as late as Xenophon we can find a sentence like δύο καλώ τε καὶ ἀγαθὼ ἄνδρε τέθνατον, “two fine and brave men are dead”,[17] where both nominal and verbal forms are dual: ἄνδρε (andre), “two men”, and τέθνατον (tethnaton), “they are both dead”. The same sentence could be written with plural forms as δύο καλοί τε καὶ ἀγαθοὶ ἄνδρες τεθνᾶσιν.

The dual persisted longer in Attica than anywhere else, but was increasingly restricted to things that came in natural pairs, and usually required the explicit word δύο (duo), “two”. It died earlier in the Ionic dialect, and already in the Homeric poems it is treated as an archaic feature, where even with a natural pair like hands the plural χεῖρες (kheires) outnumbers the dual χεῖρε (kheire), “two hands”, which survives only in places where the plural form would be unmetrical.

The dual’s zombie-like death in the oral tradition left a number of monstrous constructions in its wake:

- In Iliad 5.487, while addressing Hector, Sarpedon speaks of all the Trojans using the dual participle ἁλόντε (halonte), “having both been captured”, which is hard to explain unless it divides the population into Hector and the others.

- In lines 8.73–4, the plural subject κῆρες (kēres), “death spirits”, governs the dual verb ἑζέσθην (ezesthēn), “they both sank”, as well as the plural ἄερθεν (āerthen), “they rose”, in αἱ μὲν Ἀχαιῶν κῆρες ἐπὶ χθονὶ πουλυβοτείρῃ / ἑζέσθην, Τρώων δὲ πρὸς οὐρανὸν εὐρὺν ἄερθεν, “on the one hand, the death spirits of the Achaeans sank upon the much-nourishing earth, while those of the Trojans were raised to the wide sky.” Perhaps the dual verb depends on the conceptual duality of τάλαντα (talanta), “a pair of scales”, in line 69 rather than the κῆρες themselves?

- In a curious passage at Odyssey 8.48–9, the dual is used of 52 subjects: κούρω δὲ κρινθέντε δύω καὶ πεντήκοντα / βήτην, “fifty-two chosen youths went”. The dual forms κούρω (kourō), “two youths”, κρινθέντε (krinthente), “having both been chosen”, and βήτην (bētēn), “they both went”, are all apparently used under the influence of the word δύω (duō), “two”, despite the multitude of the actual number δύω καὶ πεντήκοντα, “fifty-two”.

The most famous crux, however, involves the embassy in Book 9 of the Iliad. The five-person embassy consists of three prominent leaders, Phoenix, Ajax, and Odysseus, as well as the heralds Odios and Eurybates, and yet they are described by the narrator and addressed by Achilles with both dual and plural forms. The Greek scholar Aristarchus suggested that Phoenix was sent ahead, leaving Ajax and Odysseus as a pair, but in that case Achilles would hardly have been surprised by their arrival; other scholars, including Zenodotus, suggested rather implausibly that the dual was interchangeable with the plural. For some modern scholars, this has been evidence that the Iliad was a careless patchwork, while others have detected a deliberate and allusive fusion of distinct traditions.[18]

The Iliad may also preserve an ancient Indo-European usage known as the elliptical dual. Rather like the associative use of we to mean “myself and others”, one member of a well-known pair could stand in the dual for both members. In Sanskrit, for example, we find the dual pitárā for “father and mother” instead of “two fathers”, áhani for “day and night” instead of “two days”, and Mitrā́ for “Mitra and Vauruna” instead of “two Mitras”. There may be an echo of this use in the Latin plural Castores for “Castor and Pollux”.

In the Iliad, the dual Αἴαντε (Aiante), “the two Ajaxes” (singular Αἴας (Aiās), “Ajax”), can refer to Telamonian Ajax and Oilean Ajax, but in some cases it clearly refers to Telamonian Ajax and his brother Teucer, which is more in line with the Indo-European elliptical use. As the dual waned in Greek, and knowledge of the elliptical dual disappeared altogether, Αἴαντε was apparently reinterpreted in a way that made sense to the poets. It has even been suggested that Oilean Ajax – Αἴας μείων (Aiās meiōn), the lesser Ajax – was a character fabricated in an attempt to explain an obsolete grammatical form.

Parsing the world into meaningful units is a marvelous feat of human cognition. The curiosities of grammatical number within and between languages often point to the most interesting details of this largely subconscious process. A philology student looking for a research topic might consider applying recent work in philosophy and linguistics to the Classical languages.

Nicholas Swift is a painter and independent scholar based in New York. He teaches Greek occasionally for the Paideia Institute, but would love to give you private lessons. He has previously written for Antigone on what ancient languages sounded like.

Further Reading

Otto Jespersen has two pioneering chapters on number in his Philosophy of Grammar (George Allen & Unwin, London, 1924), which are still worth reading. For an introduction to more recent work in linguistics, see Greville Corbett’s Number (Cambridge UP, 2001) or The Oxford Handbook of Grammatical Number (Oxford UP, 2021), and for related work in philosophy see Salvatore Florio and Øystein Linnebo’s The Many and the One: A Philosophical Study of Plural Logics (Oxford UP, 2021). Modern Greek has been the focus of much work on mass nouns because of its pluralizing freedom, and this may prove valuable for the study of Ancient Greek as well; see, for example, Evripidis Tsiakmakis et al. “The Interpretation of Plural Mass Nouns in Greek,” Journal of Pragmatics 181 (2021) 209–26.

Many of the best observations on Greek and Latin number are scattered in commentaries and grammars. Gildersleeve’s brevity is remarkably insightful in his Syntax of Classical Greek (American Book Co., New York, 1900–11). Jacob Wackernagel has five lectures on number which are now available in English as Lectures on Syntax (Oxford UP, 2009). More recent chapters on number in Greek can be found in The Syntax of Sophocles by A.C. Moorhouse (Brill, Leiden, 1982) and Greek Poetic Syntax in the Classical Age by Victor Bers (Yale UP, New Haven, CT, 1984).

Notes

| ⇧1 | Dion. Hal. Thuc. 49. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Greek and Latin verbs are formed on various tense-stems which carry their own meaning. The present stem indicates uncompleted action, and is used in both languages to form present-tense verbs, but also imperfect-tense verbs for uncompleted action in the past. Greek has an ‘aorist’ stem for completed action and a ‘perfect; stem for completed action resulting in a state; Latin has merged these two meanings into a single perfect stem. |

| ⇧3 | Pl. Rud. 1326. |

| ⇧4 | A countable noun is one that can be multiplied and counted in units, as opposed to mass nouns like mud, water, or anger. More on this in a moment. |

| ⇧5 | Ling. 9.66. |

| ⇧6 | Theb. 6.587 |

| ⇧7 | Xen. An. 3.2.31. |

| ⇧8 | Quint. Inst. 1.5.16. |

| ⇧9 | Gell. 19.8. |

| ⇧10 | Rhet. 1407b. |

| ⇧11 | BC 3.93.3. |

| ⇧12 | BG 2.6.3. |

| ⇧13 | 1.25.1. |

| ⇧14 | 5.30.1. |

| ⇧15 | An. 4.2.22. |

| ⇧16 | Hellas and Hesperia; or, The Vitality of Greek Studies in America (Henry Holt, New York, 1909) 16. |

| ⇧17 | An. 4.1.19 |

| ⇧18 | See further Greg Nagy, The Best of the Achaeans (Johns Hopkins UP, Baltimore, MD, 1979) 50f. |