Martina Björk

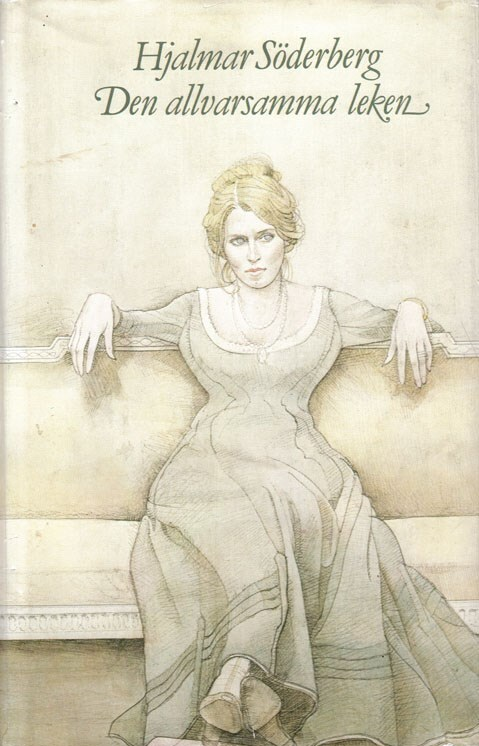

Stockholm at the end of the 19th century: a young journalist, Arvid Stjärnblom, meets the beautiful Lydia Stille in the archipelago during a summer vacation. They fall in love and begin a romantic relationship that lasts as long as the summer, and sadly comes to an end when they need to part.

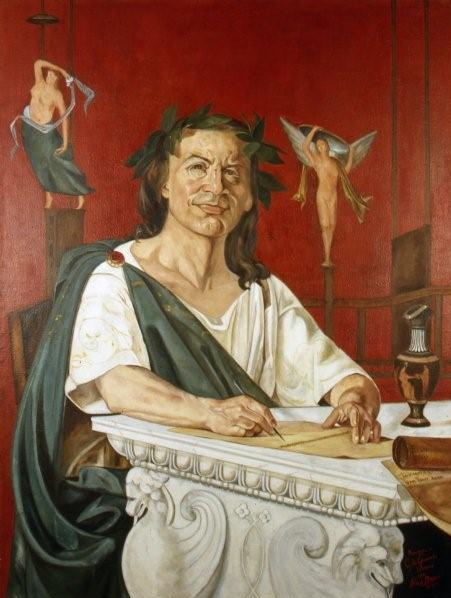

This serves as the introductory backdrop for one of Sweden’s most celebrated romance novels, The Serious Game (Den allvarsamm a leken), published in 1912 by the novelist, short-story writer, and playwright Hjalmar Söderberg (1869–1941). His works are infused with a characteristically fin-de-siècle blend of pessimism, flaneurism, and determinism. The short novel Doctor Glas (1905) is regarded as his masterpiece; the Canadian writer Margaret Atwood, who wrote a preface to the 2002 edition of the novel, is a notable admirer.[1].

When The Serious Game was adapted for the screen in 2016, under the slightly altered title A Serious Game,[2] I reread the novel and noted elements that were reminiscent of Roman Augustan poetry. However, I found no such interpretations developed within the existing Söderberg scholarship. Although Bure Holmbäck, Söderberg’s distinguished biographer, associates the name Lydia with Horace’s Lydia, and acknowledges her as part of the literary tradition, he does not take this further.[3]

That Söderberg actually was inspired by Horace (65–8 BC) is evident from a previously unknown, privately owned, letter. In 1922, an amateur poet who shared the name Lydia Stille with the novel’s heroine, wrote a letter to Hjalmar Söderberg.[4] For ten years, she had wondered whether Söderberg had borrowed her name for his successful book; now she found the courage to contact him. Söderberg responded immediately, marvelling at the remarkable coincidence. However, he wrote, he did not know about her or her poems. The name Lydia had been taken from Horace; as for the name Stille, he had just found it somewhere.

“I took her name from Horace.” That is all. Söderberg gives no further explanation. His statement woke my curiosity. Why did he choose the name Lydia from Horace? Could it be that he drew more than just the name from him? When I read the four Horatian poems that mention Lydia (Odes 1.8, 1.13, 1.25, and 3.9), I noticed multiple parallels between Horace’s poetry and Söderberg’s novel.

Let us now move back to The Serious Game. Although Arvid and Lydia part ways after their summer romance, their love is still fervent. They think of each other but do not make contact. It is mainly Arvid who acts passively, because he believes he has nothing to offer. Moreover, he believes in destiny; if they are meant to be together, Fate will intervene.

As the years go by, both marry separately.

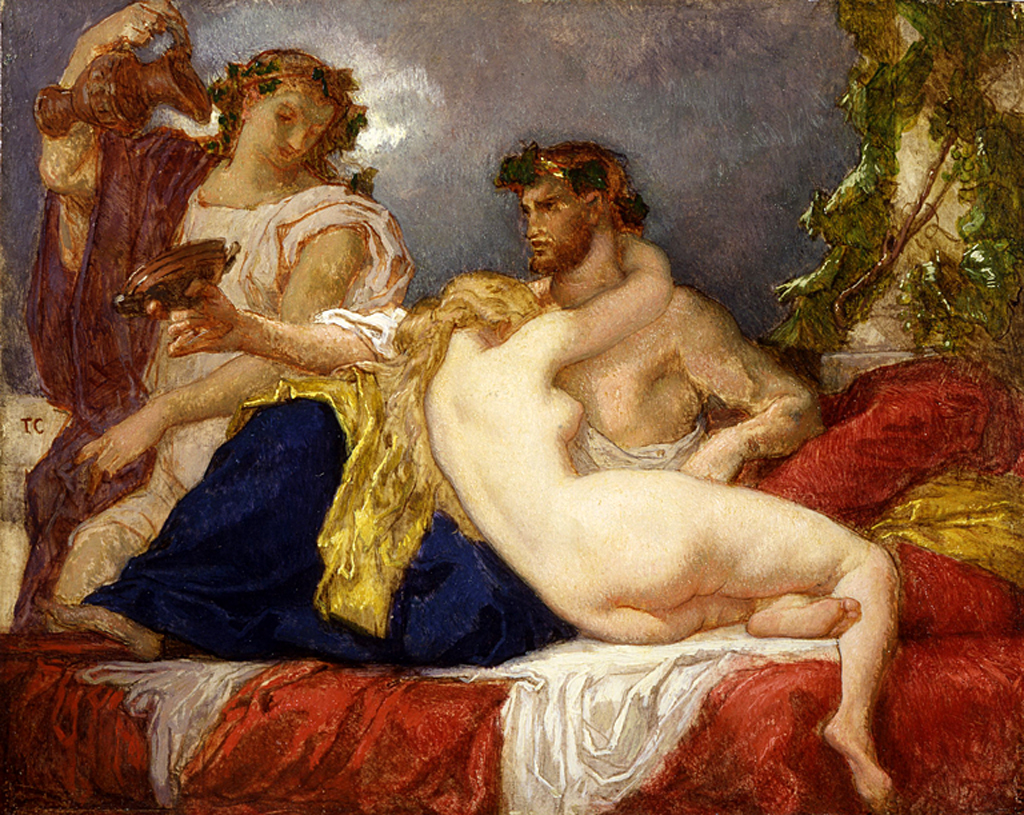

In Horace’s Ode 3.9, the speaker, the ego, whom I will refer to as “the poet”, engages in dialogue with Lydia, the woman he loves – or once loved. In each separate opening stanza, the poet and Lydia nostalgically reflect on the happiness they shared during those days (3.9.1–8). Now, Lydia loves another man, Calais, while the poet is in a relationship with a blonde woman named Chloe. The poet asks: What if Venus returns? What would happen?

quid si prisca redit Venus

diductosque iugo cogit aeneo

si flava excutitur Chloe

reiectaeque patet ianua Lydiae?

What if Venus returns as she was before, and forces under her yoke of bronze those who were separated? If blonde Chloe is thrown out, and the door stands open for the rejected Lydia? (Odes 3.9.17–20)

Ten years later, Arvid and Lydia meet again, by coincidence, at the Royal Opera House in Stockholm. Passion returns – redit Venus – and Arvid believes this to be the work of fate. It was meant to be. He cannot choose. Hjalmar Söderberg was drawn to notions of determinism that were typical of his time, and an idea of destiny that we also find in ancient mythology. For a writer interested in man’s helplessness against Fate, the presence of powerful gods in ancient mythology and literature might have been compelling.

For Arvid, his passion and love for Lydia is a life-changing experience. For Lydia, however, it appears to be different. Arvid soon becomes painfully aware that different lovers come and go in her life. He is one among many. In the novel, Lydia Stille has relationships with three other men: her husband; Kaj Lidner, a colleague of Arvid’s; and Ture Törne, a friend of Arvid’s. Horace’s Lydia also has three men besides the poet: Calais (from 3.9), Sybaris (from 1.8), and Telephus (from 1.13), two of whom belong to the poet’s circle of friends. Thus, both Lydias have one more or less stable relationship, one with the “ego” of the text, and two lovers from the main male character’s circle.

Söderberg’s Lydia shares traits with Horace’s Lydia and other alluring women from Roman Augustan poetry: she is independent, temperamental, seductive, capricious and unfaithful. In short, easy to catch but hard to keep. We find Lydia in Horace, Lesbia in Catullus, Cynthia in Propertius, Corinna in Ovid and Delia in Tibullus. These are mistresses, not loyal wives.

When the game of love becomes serious, Söderberg’s Lydia flees to another man’s embrace. “You have tormented me too cruelly and for too long,” Arvid laments. Both Lydias possess a power that can destroy their lovers.

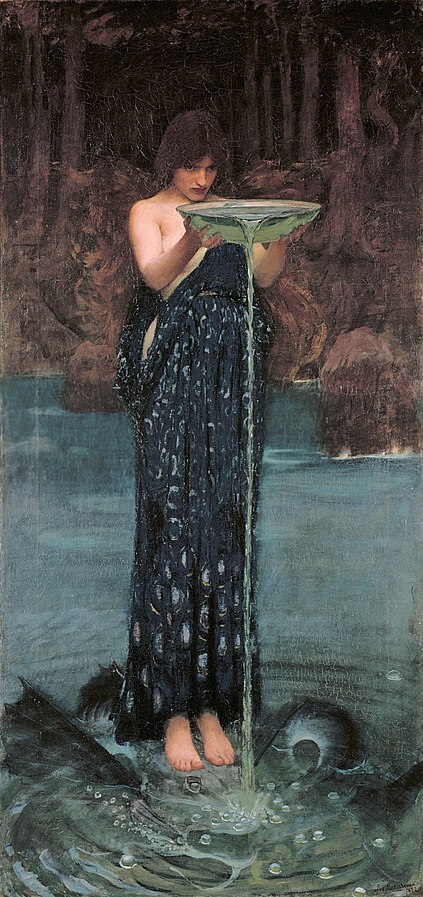

The concept of the mysterious and sexually emancipated woman who destroys men – the insatiable man-eater, the femme fatale, the female vampire who sucks life and vitality from her lover, gained popularity in the late 19th century and is well represented in art from that era featuring biblical, historical, and mythological women like Judith, Salome, Medea, Circe and Cleopatra. Although Söderberg makes her a more nuanced character, still Lydia Stille embodies this idea,[5] and Söderberg found in Horace’s Lydia an equivalent.

The power of destruction is visible in Horace’s Ode 1.8, where the poet expresses his despair over her power over Sybaris. Her love destroys him.

Lydia, dic, per omnes

te deos oro, Sybarin cur properes amando

perdere?

Lydia, I beg you for all gods’ sake, tell me why you are in such a hurry to destroy Sybaris with your love? (Odes 1.8.1–3)

Arvid’s colleague, Kaj Lidner, one of Lydia’s lovers, unexpectedly commits suicide on Christmas Day, and it is strongly hinted that Lydia Stille is the trigger. The day before, Christmas Eve, he had repeatedly rung her doorbell, but she did not open – because someone else was inside with her, namely Arvid.

She did not open the door. Arvid himself will experience the same humiliation of being shut out. Part four of the novel circles around Lydia’s apartment, into which she has moved after leaving her husband. Frequently, Arvid gazes at her window to see whether she is home. When she is, two candles are lit. Yet, even though he knows she is inside, she does not open the door for him. In anger, he writes her a letter, declaring: “You will never see me again as a wrecked beggar for love outside your door.”

Here, a significant literary motif can be discerned, present in ancient poetry: the Greek paraklausithyron (from παρακλαίω, paraklaiō, “mourn beside”, and θύρα, thyrā, “door”) – “to mourn before a door” – expressing the sorrow of a locked-out lover, which in Roman poetry is represented by the exclusus amator, the shut-out lover. Arvid is an exclusus amator, sometimes welcomed, sometimes not. Bitterly, he realizes that he cannot hope for anything from Lydia, who “seduces man after man, never settling down until old age or death brings the supply to an end.”

In Horace’s Ode 1.25, a desire for revenge is expressed: a wish that life will judge righteously so that Lydia too will experience the pain and humiliation of being rejected. The poet realizes that only one thing can stop the traffic to her bedroom: age. When Lydia is old, her lovers will no longer line up outside her door.

Parcius iunctas quatiunt fenestras

iactibus crebris iuvenes protervi,

nec tibi somnos adimunt, amatque

ianua limen,

quae prius multum facilis movebat

cardines; audis minus et minus iam

“me tuo longas pereunte noctes,

Lydia, dormis?”

invicem moechos anus arrogantes

flebis in solo levis angiportu.

Less often, young men eagerly beat your shuttered windows or steal away your sleep. Now, your door loves the threshold, which easily used to move its hinges. Less and less often you hear: “Lydia, are you sleeping, while I, your lover, perish through this long night?” Instead, you will weep in some desert alley over your arrogant adulterers, as an old woman of no value. (Odes 1.25.1–10)

Horace and Söderberg arrive at the same conclusion: only age or death can stop her amorous affairs, only age or death can stop the destructive force that is Lydia.

Later in the same poem, Lydia is associated with fall and winter. Spring has passed. The north wind brings winter and withered leaves. Winter is also the dominant season in The Serious Game. Perhaps this reflects how Arvid’s and Lydia’s relationship is doomed. Once (in part three), Lydia laments: “Oh, Arvid—why must we reach the autumn of our lives while still so young?” Arvid replies, “Autumn has come too soon for us”, and “Autumn has come too early”. Outside, church bells toll for the dead king and will ring again in the December darkness. Horace’s and Söderberg’s Lydias belong to winter, while Horace’s blonde Chloe in Ode 1.23 is associated with spring.

In the second part of the novel, Arvid asks his doorkeeper of the hair colour of the lady who has left flowers for him on his birthday: “Blonde or dark?” “Blonde” is the answer. The flowers come from his wife-to-be, Dagmar. The question is echoed in the fourth part, when Lydia asks, during one of their secret rendezvous: “Is she blonde or dark?” “Blonde,” Arvid replies. That Dagmar is blonde and Lydia dark-haired is stressed more than once. Arvid’s blonde Chloë is his wife, Dagmar.

This may explain why Söderberg characterizes Arvid’s marriage to Dagmar as happy, despite Arvid’s skeptical view. For Arvid, his marriage is a lie. He never loved Dagmar, while what he experiences with Lydia is true and genuine. Part three in the novel begins: “Arvid and Dagmar Stjärnblom lived a very happy life together.” On the following page it reads: “Arvid lived very happily with his wife.” The chapter closes with: “Otherwise, they lived together very happily.” A parallel is visible in Horace’s felices ter, “three times happy,” in Ode 1.13:

felices ter et amplius

quos irrupta tenet copula nec malis

divulsus querimoniis

suprema citius solvet amor die.

Three times happy and more than that are those whom an unbreakable bond holds fast, and whom estranged love does not part with vicious quarrels before the final day. (Odes 1.13.17–20)

Both Söderberg and Horace praise faithful love, or rather, they celebrate those who can peacefully cherish the bond of marriage that Venus must not break, those who are fortunate enough not to become playthings of the gods. Happy are those whose lives Fate or the gods do not interfere with.

Quid si prisca Venus redit? What if Venus returns as she was before? What would happen if she returned to two former lovers? Horace asked the question; Hjalmar Söderberg answered it. Not only did Söderberg take the name Lydia into his novel; he also introduced the entire concept of Lydia from her Roman poetic context. From the same ancient literary tradition, Söderberg wove motifs and ideas into his work, which also suited contemporary trends in literature.

Lydia is not merely a creation of Roman poets’ imaginations, Söderberg seems to suggest. She is a female archetype, a universal phenomenon not confined to a specific time or place, but present in every decade and every culture – a force of nature that cannot be tamed.

In a passage from the fourth part of The Serious Game, Arvid hears of another unfaithful woman who lived forty years earlier: “So, there was a Lydia in the 1870s as well,” he says to himself. “Yes, I suppose there has always been one, and there always will be. She is eternal, like nature.”

Martina Björk is an affiliated Latin scholar at Lund University, Sweden.

Further Reading

R. Ancona, ”Female Figures in Horace’s Odes,” in G. Davis (ed.), Blackwell Companion to Horace (Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, 2011).

B. Holmbäck, Hjalmar Söderberg: ett författarliv (Bonnier, Stockholm, 1988).

T.S. Johnson, “Locking-in and locking-out Lydia: lyric form and power in Horace’s C. I.25 and III.9,” Classical Journal 99.2 (2004) 113–34.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Atwood’s introduction to Doctor Glas was published in the 2002 edition of the novel, translated into English by Paul Britten Austin. See also Margaret Atwood: ”Death and the Maiden”, The Guardian 26 Oct. 2002, available here. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | A Serious Game (2016), directed by Pernilla August (Nordisk Film, Sweden). |

| ⇧3 | “Her name carries a subtle association with one of the most important female portraits in Horace’s work” (my translation). B. Holmbäck, Hjalmar Söderberg: ett författarliv (Bonnier, Stockholm, 1988) 373; see also B. Holmbäck, Det lekfulla allvaret (Bonnier, Stockholm, 1969) 150. |

| ⇧4 | The letter is cited by Kurt Mälarstedt in “Hon är evig som naturen”, Dagens Nyheter, 14 Feb. 2009. Mälarstedt found the letter during his work on Ett liv på egna villkor (2006), a biography of Maria von Platen, the woman who is believed to have been the model for Söderberg’s female characters Lydia (The Serious Game), Helga (Doctor Glas, 1905) and Gertrud (Gertrud, 1906). |

| ⇧5 | See for example Holmbäck (1969, as n.3) 148–53. |