Edmund Racher

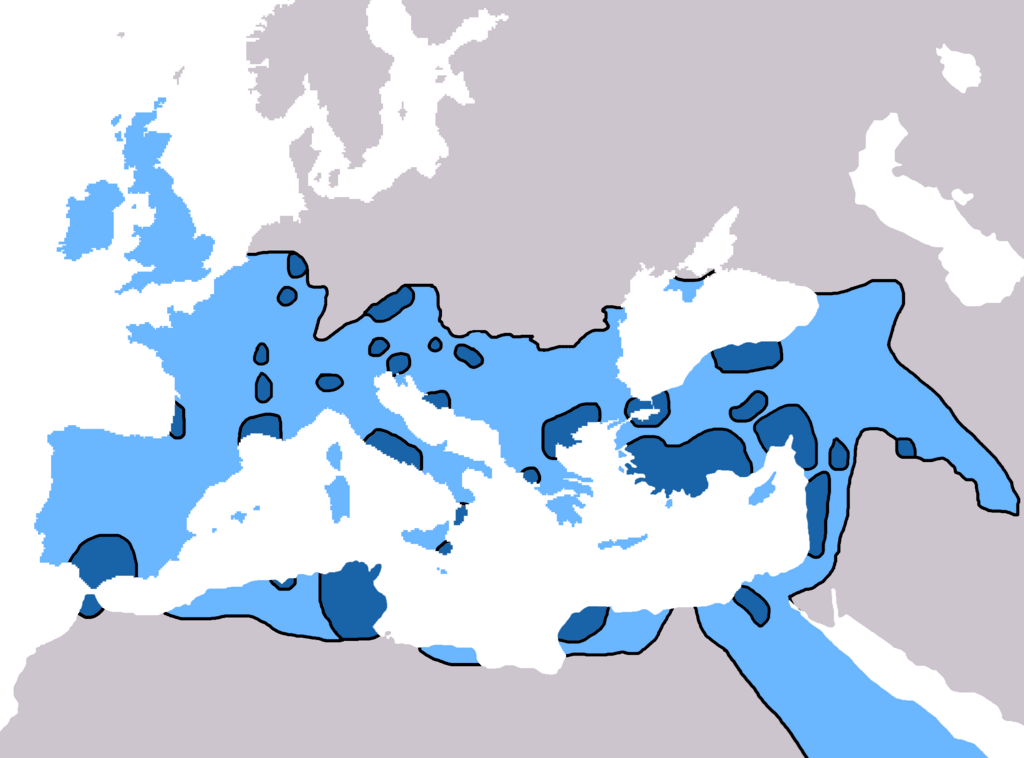

Outside York Minster is a statue of Constantine the Great (AD c.272–337) – the Emperor who reunited the Roman Empire and set it on the path towards tolerating, recognising and finally establishing Christianity. The placement of the statue is no error. York (then called Eboracum) was the site where he was first proclaimed Emperor. It’s rather a good depiction: the statue shows Constantine in military dress, seated on a throne (rather than a curule chair), and the face is of a kind with statues of the Emperor made in the 4th century. He slouches somewhat and supports a sword with a broken tip. On the base of the statue is the familiar phrase (in English): “By this sign conquer.”

Here we have our image of Constantine: a ruler combining military and civil authority, significant but not quite ‘upright’. The statue was installed by the York Civic Trust in 1998; the potted history of Constantine on their website sets the scene. York’s statue points to a continuing interest in Constantine in Britain, both as a figure with local ties (though historically exaggerated – of which more below) and as a vital figure of late antiquity.

However, there are more complex depictions of Constantine for a mass audience in Britain than the statue in the centre of York. Dramatisations of his life since the end of the Second World War both reflect and illuminate a great deal about how we view not just the ancient world but the society and culture of our own times. How has this pivotal figure in Christian history been depicted for mass audiences?

Dorothy L. Sayers and Constantine

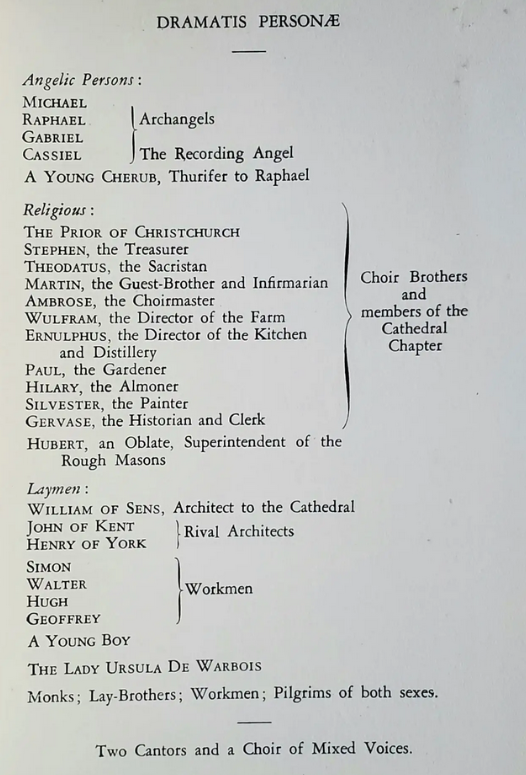

We begin with The Emperor Constantine, a 1951 play by Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957). Sayers may be best known for her detective fiction, but she had a wide range of literary interests; As Josey Wright reminds us, Sayers inspired the Christian Classical Education movement with her 1947 essay “The Lost Tools of Learning”. Her oeuvre includes literary criticism, a translation of Dante, several advertising campaigns, and a series of dramas on historic and religious themes. She won acclaim for her first major play The Zeal of Thy House (1935), which deals with the rebuilding of Canterbury Cathedral in the 12th century; her cycle of radio plays The Man Born to Be King (1941–2), which sparked some minor controversy when first broadcast on account of its unorthodox use of contemporary colloquial language, deals with the life of Jesus Christ.

In 1951, the organisers of the Colchester Festival (part of the Festival of Britain), together with the Rt Revd Frederick Dudley Vaughn Narborough, Suffragan Bishop of Colchester, wished to commission a play about St Helena. In a conceit associated most strongly with Geoffrey of Monmouth (c.1095–1155),[1] Helena had long been held to be the daughter of King Coel of Colchester, the legendary “Old King Cole” of the nursery rhyme.

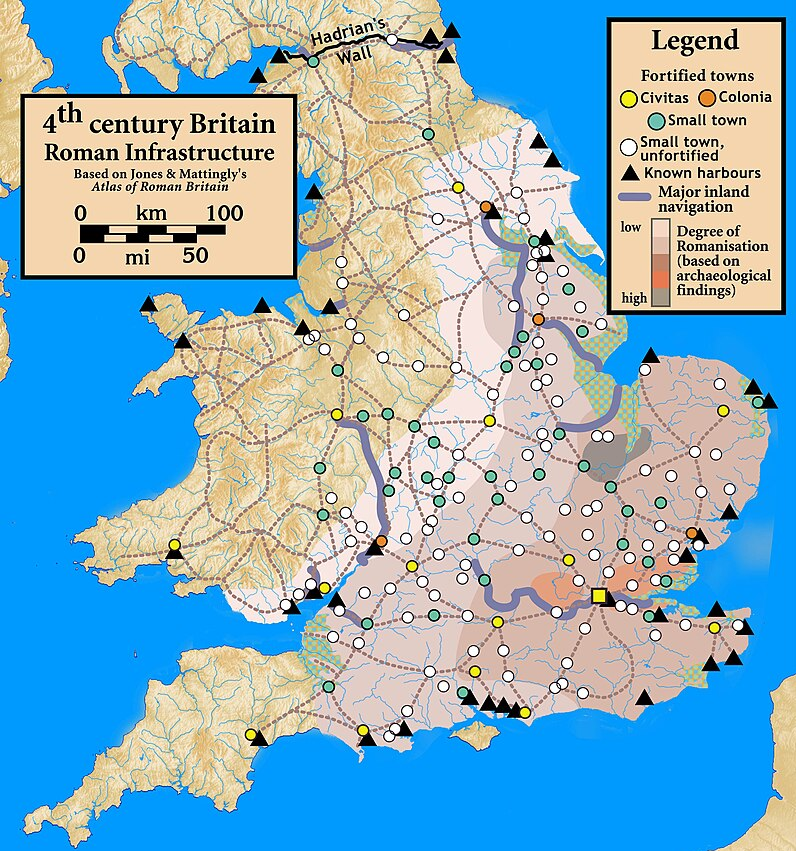

This seems to have been an ideal subject for the Colchester Festival, the city having been an important site, Colonia Camulodunum, in Roman Britain. Colchester Town Hall still features statues and stained glass in memory of St Helena: local schools, hospitals and churches are named after her. The city’s coat of arms boasts not just the three crowns of East Anglia but also a cross: not the plain geometric cross of usual heraldry, but two ‘ragged staffs’ pierced with nails.[2] A crowned female figure holding a cross appears on the crest of the helmet. At least on the level of civic iconography, affection for Helena remains. However, it seems that St Helena was not quite the right subject for Sayers, as she made plain in a letter to an Orthodox priest in Helsinki.[3] She instead took up the story of Helena’s son Constantine.

The Emperor Constantine on stage

The Emperor Constantine begins with a prologue by a personification of the Church; then the first scene unfolds at the court of King Cole of Colchester. Helena greets her divorced husband, Constantius Chlorus (c.250–306) and her grown son, Constantine. Cole (accompanied by – yes! – three fiddlers) prophesies great events to come for the young prince. We are introduced to the Briton Togi – Latinised as Togius – who will serve Constantine in the future.

From here onwards, the play follows recorded history more closely: we see Constantine proclaimed Emperor by the army in York; then he allies precariously with Diocletian’s retired co-emperor Maximian (Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus, c.250–July 310), whose daughter Fausta (Flavia Maxima Fausta, 289–326) he has married. Constantine then orders the famous ‘Chi-Rho’ symbol (☧) to be painted on his army’s shields prior to a pivotal confrontation with Maximian’s son Maxentius (Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius, c.283–28 October 312).

The ‘Chi-Rho’ symbol is a ‘Christogram’ (abbreviation of the name ‘Jesus Christ’) consisting of the superimposed Greek letters chi (Χ) and rho (Ρ), which are the first two letters of χριστός (christos), the Greek for ‘Christ’. This is most likely not something a committed pagan emperor would do. Constantine also introduces bishops to his court, and causes murmurs among his army by using Christian prayers. Finally, he confronts his brother-in-law Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (28 October 312). Maxentius dies after losing the battle; Constantine takes Rome, delighting the Christians in his army and provoking a wry sort of dismay among the old senatorial families. All of this takes place in the play’s first act.

The second act deals with Constantine as Emperor in the West, and his family life as the husband of Fausta. His son from his first marriage, Crispus (Flavius Julius Crispus, c.300-c.326), and is often in the company of Helena and Constantia (Constantine’s half-sister, c.293-c.330). Friction arises between the ‘heathens’ in positions of power and the growing proportion of Christians in the state; this is exacerbated by the openly Christian faith of Helena and Constantia, and Constantine’s own attitude of benevolent neutrality in religious matters. Meanwhile, Christianity itself is in danger of being split apart by internal debates.

In 324, Constantine and Crispus defeat Licinius (c.265–325), Emperor in the East, in battle at Chrysopolis, even though Licinius received countless pagan blessings. Constantine, despite the increasingly prominent Christian presence at his court, still wishes to present himself as a symbol suitable for Christians and pagans alike. However, he is prevented from doing so owing to the growing schism within the Church. Something needs to be done.

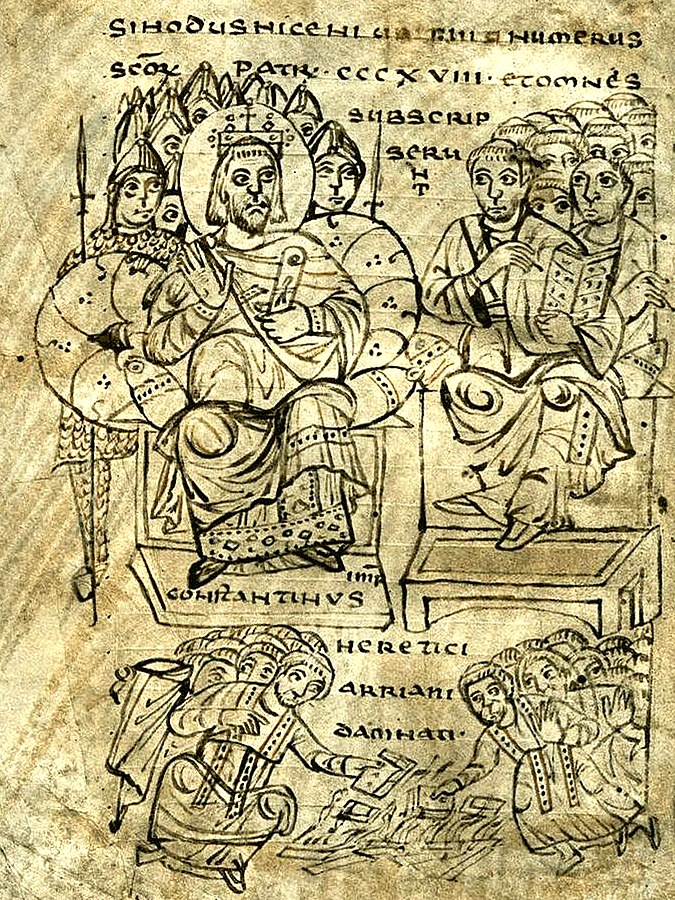

The Third Act sees Constantine attempting to maintain peace in his Empire, and within the Church, by convening the Council of Nicaea (May–July 325) to attain consensus and unity among the world’s Christians. Many of the now-standard orthodox doctrines of Christianity were confirmed at this council; when Catholics, Orthodox Christians, Anglicans and ‘mainline’ Protestants recite the ‘Nicene Creed’, they are making a statement of faith that confirms their acceptance of the doctrines that were promulgated at Nicaea. The Council marked the beginning of a struggle between St Athanasius, Archdeacon of Alexandria (c.296/8–373), who suffered throughout his life for his steadfast championing of Nicene theology, and the followers of Arius (250/6–336), who is now known as the founder or codifier of the Arian heresy.

Sayers depicts the Council in detail, setting the stage for it with street-scenes in the town beforehand; the Council itself is treated somewhat in the manner of a courtroom drama. St Athanasius and Arius both get long speeches outlining their respective positions. While the various prelates debate Christian doctrine, Fausta, now alienated from her husband Constantine, begins flirting with conspiracy, and falsely accuses Crispus of rape. Constantine has him killed – and then the truth of the matter is revealed by Togi. A despairing Constantine takes action against the conspirators, although he initially spares Fausta for the sake of appearances. In the play’s epilogue, Constantine converts on his deathbed; the prophesying Cole returns to the stage, as does the personified Church, who leads a growing number of voices in the Nicene Creed as the play ends.

Some photographs and costume designs remain from the original production of The Emperor Constantine; a few may be seen in the fourth volume of Sayers’ letters.[4] These show a highly ornate costume for Constantine, contrasted against plainer Churchmen at Nicaea, and a distinctly Romantic-looking King Cole. Contemporary reception of The Emperor Constantine appears to have been mixed: critics were not altogether kind, but audiences (at least by Sayers’ account) seem to have particularly enjoyed the Council debates in the third act.

Constantine on TV

Next to consider is the 2006 BBC series Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. This was a dramatised documentary series broadcast between 21 September and 26 October; it comprises six episodes, on: Julius Caesar (100–44 BC); Nero (Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, 37–68); the Jewish Revolt of 66 during the reign of Nero, suppressed by the emperor-to-be Vespasian (Titus Flavius Vespasianus, 9–79, r. 69–79); the Gracchi (Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, c.163–133 BC, and Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, c.154 –121 BC); Constantine; and the Sack of Rome in 410 by Alaric, King of the Visigoths (c.370–411).

The fifth episode, on Constantine, was directed and produced by the television veteran Tim Dunn, and written by the Revd Dr Colin Heber-Percy and Lyall Watson. Constantine is played by David Threllfall, who was then 52 years of age. The episode is partially narrated by Alisdair Simpson, who fills in gaps in the narrative with essential historical context. At the beginning, Constantine is seen marching on Rome, which is then held by Maxentius (who is specifically referred to as tyrannical). The action initially concentrates on the build-up to the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, with Constantine painting the Chi-Rho on his soldiers’ shields while Maxentius consults the entrails of sacrificed animals for omens; he intends to lead Constantine into a trap.

Constantine is advised by the author Lactantius (Lucius Caecilius Firmianus, c.250–c.325). The famous sign of the cross that appeared in the sky before the battle is mentioned by the narrator rather than any of the historical figures, thus giving the appearance of authorial impartiality, or even scepticism, with respect to events that we know best through descriptions in the Christian writers Eusebius of Caesarea (c.260–339) and Lactantius.

Maxentius is defeated, in a rather dusty battle between disorganised mobs of men. Constantine enters Rome as a liberator in several brief but melodramatic scenes. He is drawn slowly into Christianity by Lactantius, even visiting a Church in a ‘Christian quarter’, around the time that his half-sister Constantia marries Licinius, who views official toleration of Christianity in pragmatic political terms. In this telling of the story, Constantia has a close relationship with Constantine, perhaps purely for the sake of heightened dramatic tension.

Eventually, relations between the Empires of East and West break down. Licinius is defeated at Chrysopolis, with a vast labarum (λάβαρον, labaron, an imperial military standard featuring the Chi-Rho symbol) being unveiled as a kind of secret weapon that terrifies the Eastern forces. Constantia begs for her defeated husband’s life; he is kept under house arrest. Then, out of nowhere, the Council of Nicaea is abruptly introduced to the narrative.

A now all-but-explicitly Christian Constantine describes the Council as a means of unifying the empire. This unification apparently also requires the death of Licinius and his son. Their deaths are shown as part of a montage that is cross-cut with Constantine reciting the Nicene Creed in front of the Council’s assembly of bishops. This might be an homage to the final section of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), in which the new head of the Corleone crime family stands by the font to serve as godfather during the baptism of his niece whilst his hitmen assassinate various members of rival gangs.

It is worth noting that the Creed is not recited in full in this scene: the section on the nature of Christ is cut, for whatever reason. In the aftermath of the Council (and the assassinations), Constantia is angry at Constantine, not only for the deaths of her husband and son, but also for how he has supposedly changed Christianity. The episode closes with the final Amen of the Creed; the fate of Constantine’s ill-starred wife Fausta is noted in a written ‘title card’ before the credits.

The costumes and art direction of Ancient Rome are worthy of note. Constantine on campaign is shown in dowdy-looking armour, but he quickly adopts impressive purple and gold garments after he takes Rome. This serves to differentiate him from Licinius and his forces, who seem to be clad uniformly in unimpressive reds; this might also signal a ‘Byzantine’ splendour as part of Constantine’s legacy. The attitude towards the labarum only reinforces this impression.

The casting of Ancient Rome is very telling. As Constantine, Threllfall is curly-haired and boasts relatively delicate features, although this is not very close to the portraits of Constantine that can be seen on coinage and statuary. It is tempting to believe that this is a deliberate visual parallel to Caligula (Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, 12–41) as memorably portrayed by John Hurt in the 1970s BBC series I, Claudius. Lactantius and the Christian community in their first appearances are deliberately humble in appearance – their garments are not only plain, but downright coarse. The Christian quarter Constantine that visits is walled-in and dark; there are conspicuously shabby sections in the dimly-lit Church he visits. Christianity, in this series, is a distinctly low-status phenomenon.

Constantine on Radio

Finally, we turn to the radio drama Caesar! by Mike Walker.[5] These were broadcast by the BBC on Radio 4 between 2003 and 2007 in three series, each of three hour-long episodes. Based on the work of Suetonius (at least in the first series), Caesar! nominally focuses on one emperor (or imperial figure) per episode. The first series covers Julius Caesar, Octavian/Augustus (63 BC–AD 14) and Caligula; the second Nero, Hadrian (76–138) and the successors of Marcus Aurelius (121–180); the third Victoria (c. 231–c. 271, mother of Victorinus, the ruler of the breakaway Gallic Empire), Constantine and Romulus Augustulus, the last Emperor in the West (c.465–post 511). Constantine’s episode is subtitled ‘The Maker of All Things’.

‘The Maker of All Things’ begins with Constantine (played by Sam Dale) contemplating his father’s death in Britain, “a God-forsaken country.” Thereafter we proceed directly into his confrontation with Licinius; this provides an excuse for some exposition on the division of the empire under Diocletian (c.242–311). There is hope for peace between them. The marriage of Constantia is mentioned, if not explored; Licinius expresses discomfort with Constantine’s toleration of Christianity.

However, the drama’s action focusses on Constantine’s court. He is advised both by Fausta and Helena – the one cynical, the other devout – with his son Crispus as an eager protégé. A clash with Licinius is regarded as inevitable; Crispus is dispatched to help deal with it, as a means of growing up and gaining military experience. He is escorted by the old soldier Rufus.

In time, Crispus leads Constantine’s forces to victory at the Battle of the Hellespont (Chrysopolis is not shown). He returns to Constantine’s court, gradually being elevated from General to Imperial Heir. Fausta takes him under her wing to assist, ostensibly to teach him social graces, but really to seduce him. Helena confronts her over this, without diverting the course of events. With the empire united and his military reforms in place, Constantine next turns to resolve the schism in the Church, and convenes the Council of Nicaea.

Arius and Athanasius are both given a chance to air their views, though Constantine reveals to Crispus that the resolution of the Council has been pre-arranged, with Athanasius’ side having the greater numbers. Constantine believes that numerous Christians are good citizens, and faithfully follow the Gospels’ injunction to render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s. When Constantine is pressed by Crispus on the extent to which he believes in Christian teachings, his answer centres on the unifying, inhuman figure of the Emperor – who is neither questioned on what he believes, nor on much else.

Constantine’s peace does not last: Crispus, prompted by Helena, rejects Fausta. The loyal, distressed Rufus is directed to kill Crispus, and then commits suicide himself.[6] Constantine reveals that Fausta accused him of rape: Helena vehemently denies this.

Constantine, distressed by the loss of his son, is confronted by Helena over this pointless killing. He suppresses his grief, claiming ”no one ever died of a bad conscience”; even so, he dispatches Helena to find the True Cross and pledges to convert fully to Christianity to achieve God’s forgiveness. Meanwhile, he continues to unify the Empire. A sorrowful Helena acquiesces. The vengeful Constantine has Fausta killed in her bath, in a somewhat grisly scene. When her screams subside, Constantine prays earnestly to God the Father, hoping to salve his conscience. The episode ends with his private recitation of the Lord’s Prayer in Latin.

Common Threads and Divergent Points

There are several common threads running through these depictions of Constantine’s life. Each writer seems to have recognised the possibilities of family drama in the life of Constantine. ‘The Maker of All Things’ makes the most of this, but even Ancient Rome acknowledges it, particularly with respect to Constantia, even as it abridges or ignores other aspects of Constantine’s life. The Emperor Constantine is rather tamer than ‘The Maker of All Things’, though the difference in tone, approach and focus result in part from changing tastes, and the nature of stage versus radio drama (to say nothing of the concerns of two very different writers). The death of Fausta, as shown in ‘The Maker of All Things’, might be difficult to perform onstage without melodrama or bathos.

Each of these dramas demonstrates a different attitude towards Constantine’s personal connection to Britain. The Emperor Constantine embraces it, while dismissing as lazy or malicious rumour Helena’s Illyrian birth and low status. Helena and Constantine discuss this in language that seems to a modern ear to be unmistakably characteristic of middle-class British life in the 1950s. The presence of Togi/Togius as Constantine’s loyal servant and conscience only serves to reinforce the British connection. Ancient Rome, by contrast, makes no mention of Britain, while ‘The Maker of All Things’ has Constantine speak disparagingly of Britain. Further, rather than being a straight-forward Romano-British princess, Helena mentions her past as a prostitute at a tavern in an unspecified province.

Constantine, the Church, and Schism

The power of the Christian Church during the reign of Constantine varies dramatically between the three historical dramas that we have been examining. Ancient Rome gives no hint of the Church as having much in the way of agency, beyond the efforts of Lactantius to advise the emperor in ways that favour Christianity. The Christian Quarter is depicted as inward-looking and semi-clandestine, despite the fact that much of the Empire had already been Christianised even in the face of the persecutions of Christians under Diocletian.

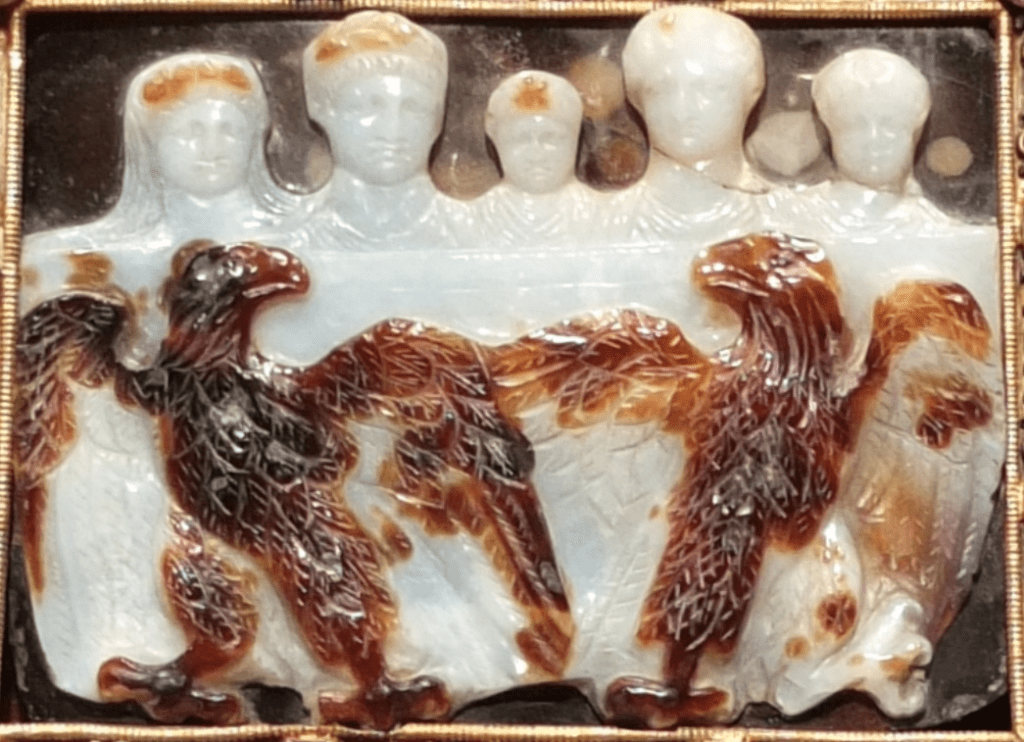

Indeed, according to Eusebius, in his Historia Ecclesiastica, the Church in Rome had as many as 154 employees, and supported more than 1,500 people through charitable activities.[7] Even in the distant province of Britannia, Christians were able to produce something as impressive as the Hinton St Mary Mosaic, which was surely not hidden furtively from view.[8]

Attitudes to the Church’s inner turmoil differ significantly in these dramatisations. That any kind of debate has even been going on in the Church is not entirely clear from Ancient Rome‘s version of the Council of Nicaea. ‘The Maker of All Things’ gives the Council some space, though suggests that Constantine had already predetermined what the outcome ought to be.

The Emperor Constantine presents the Council as more of a courtroom drama, with separate sides stating their cases, a style of exposition that Sayers employed more than once in her novels and plays. Constantine himself notes the failure of other Councils to resolve the Church’s divisions, and thus decides to put the power of the state decisively behind the sessions at Nicaea.

Accordingly, as Chair (and thus ‘Judge’), Constantine educates himself in the question of the relation of God the Father to God the Son. At last he becomes convinced by the Catholic position over the Arian one, and is determined to guide the Council into a position that would not give the Arian position leeway (and thus provoke another Council on the same set of questions a generation later).

“The Dogma is the Drama”?

It is clear from Sayers’ presentation of the debates at Nicaea that these were questions that needed to be settled as a matter of urgency for the Church. Even if the Emperor securely backed one side, the debate was still essential – indeed, crucial. Sayers herself said as much in an essay of 1939 entitled ‘The Dogma is the Drama’,[9] on her earlier work The Zeal of Thy House:

The action of the play involves a dramatic presentation of a few fundamental Christian dogmas – in particular, the application to human affairs of the doctrine of the Incarnation. That the Church believed Christ to be in any real sense, God, or that the Eternal Word was supposed to be associated in any way with the work of Creation; that Christ was held to be at the same time Man in any real sense of the word; that the doctrine of the Trinity could be considered to have any relation to fact or any bearing on psychological truth; that the Church considered Pride to be sinful, or indeed took any notice of sin beyond the more disreputable sins of the flesh: – all these things were looked upon as astonishing and revolutionary novelties, imported into the Faith by the feverish imagination of the playwright. I protested in vain against this flattering tribute to my powers of invention, referring my inquirers to the Creeds, the Gospels and the offices of the Church; I insisted that if my play was dramatic it was so, not in spite of the dogma but because of it – that, in short, the dogma was the drama. The explanation was, however, not well received: it was felt that if there was anything attractive in Christian philosophy I must have put it there myself.

The question of how far Constantine believed in the doctrines of Christianity is a constant in all of these dramatisations. None portrays him as outright delusional (as in Waugh’s Helena), though Ancient Rome may hint at it. Constantine clearly believes himself to be special (indeed exceptional) in ‘The Maker of All Things’, as in The Emperor Constantine, but Sayers clearly concludes that such a belief can align with orthodox, sincere Christianity without internal contradiction. The writers of Ancient Rome constantly hedge their bets on this matter, putting phrases in the narrator’s mouth including “no one knows what was in Constantine’s heart” and “no one knows for certain what Constantine’s army saw”.

Constantine’s role as either defender or manipulator of Christianity is an obvious point of contention. Ancient Rome puts its most dramatically charged lines in the mouth of the accusing Constantia; also, Constantine’s recitation of the Creed is made to look like something other than a sincere affirmation of personal belief. ‘The Maker of All Things’ clearly has Constantine guiding events within the Church, but by its conclusion Constantine has evidently come to have embraced Christianity personally, as well as out of political convenience.

The Emperor Constantine starts with an assertion of approval by the personified Church. But Sayers is not afraid of nuance or complexity. The following exchange occurs at the end of the play’s second act:

HELENA: I have been afraid of this. For years I have seen this coming. Our Lord said “My Kingdom is not of this world”.

HOSIUS: True, madam. Yet, when He left his disciples, He put worldly power in their charge, saying: “He that hath a purse, let him take it; and he that hath no sword, let him sell his garment and buy one.”

EUSEBIUS: He said also: “Preach the gospel to every creature.” And when all are converted, there must needs be a Christian state.

CONSTANTINE (drily): True. In that happy day there will be no poor pagan to take the burden and blame of office. Sirs, it is easy to be virtuous so long as you can criticise from outside, but it is not so easy when you have to wield power yourselves and take the consequences…

Who Got Constantine Right?

The Emperor Constantine, by virtue of both its length and Sayers’ own scholarly bent, is unquestionably the richest of the accounts of Constantine’s life that we have examined here. We can endorse the conclusion of Antonina Harbus, who said that the play’s main function was to provide a stage for the doctrine of the Trinity.[10] That said, some feel it was less than successful at this.[11]

It would be a mistake to regard The Emperor Constantine as indicative of received opinion on Constantine in Britain in 1951.[12] That it could be staged at all is telling in itself, but the play is too strongly stamped by Sayers’ own personal preoccupations to be an index of anything like a ‘national mood’.

The opposite is true of Ancient Rome, which sits quite firmly in its context as a product of the BBC during the mid-2000s: there is a marked suspicion of any alliance between Church and state; also, the writers conspicuously ignore or downplay any possibility of theological exploration. It is tempting to associate this production with the then-fashionable ‘New Atheist’ movement of the time: Constantine was seen as a problem worth addressing, whilst nobody thought to dramatise the life of Diocletian – a stabilising emperor even if he instigated the Great Persecution (promulgated on 23 February 303, and formally ended only in 311).

‘The Maker of All Things’, by contrast, was written for radio, which is a cheaper medium than film, television or theatre, and has generally been less central to the culture (at least where drama is concerned). Radio plays are principally driven by dialogue; this makes the form ideal for exploring intellectual conflicts. Walker’s Caesar! also has the strength of offering a series of dramas, which are able to lightly reference one another. On the other hand, lower budgets tend to lead to smaller casts.

‘The Maker of All Things’ can feel more like a family drama than a reconstruction of history. Of course, it doesn’t go quite as far down that route as the film The Lion in Winter (dir. Anthony Harvey, 1968), in which King Henry II’s attempt to sort out his succession at a family Christmas gathering is transformed into an absorbing drama. In ‘The Maker of All Things’, the stakes of war between the Caesars and of imperial reform, are never ignored; also, Constantine’s family members are clearly demonstrated to be driven by freestanding personal ideals as well as the conflicts of their relationships.

The story of Constantine needs flesh on its bones. We have examined three retellings of his life story that are already showing their age. It is time for a fresh version. But what will it look like, how will it differ from these three depictions, and what will it demonstrate to future generations about the world in which we live? No immediate answer is forthcoming, but an appealing project would be a radio series or podcast of Sayers’ play. The work is so conspicuously dated that it cannot take centre stage, but it is certainly rich enough to be an excellent opener for encouraging debate and public interest.

Edmund Racher, having spent some time in publishing, currently holds a minor position at Magdalen College, Oxford. Despite an MA in Medieval and Early Modern Studies, he has nursed an interest in the Classics from an early age. He has previously written for Antigone about the twilight of Rome in 20th-century fiction.

Further Reading

A. Cameron & S.G. Hall, Eusebius: Life of Constantine (Oxford UP, 1999).

N. Lenski (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine (Cambridge UP, 2012).

D. Potter, Constantine the Emperor (Oxford UP, 2013).

B. Reynolds, Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul (St Martin’s, New York, 1993).

R. van Dam, The Roman Revolution of Constantine (Cambridge UP, 2007).

Notes

| ⇧1 | See also the Old English poem Elene by the 8th-century poet Cynewulf. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | In heraldry, a ‘ragged staff’ denotes a knotted stick with short stumps of branches on each side. |

| ⇧3 | Dorothy L Sayers, The Letters of Dorothy L. Sayers, Volume 4: 1951–1957: In The Midst of Life (Barbara Reynolds ed., Hodder/Dorothy L. Sayers Soc., London, 2000) 33–41. This is, incidentally, the opposite response to Evelyn Waugh (1903–66), who published a brief novel called Helena in 1950, dealt with here. |

| ⇧4 | As n.3. |

| ⇧5 | Walker has something of a penchant for historical radio drama: an informal guide to these may be found here. |

| ⇧6 | Constantine’s filicide is treated with horror and sympathy; this contrasts with Walker’s restrained take on the death of Peter the Great’s first son Alexei in his 2017 series Tsar. Consciously or otherwise, Walker goes against the judgement of both Voltaire and Edward Gibbon on this. |

| ⇧7 | Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica 6.43.11. |

| ⇧8 | This can be seen on the British Museum website here. |

| ⇧9 | The text will be found in her collection Creed or Chaos? And other essays in popular theology (Methuen, London, 1947). |

| ⇧10 | A. Harbus, “Colchester’s legend on stage: The Emperor Constantine by Dorothy L. Sayers,” Modern Drama 48.21 (2005) 87–107. |

| ⇧11 | For example, William Reynolds, in the collection As Her Whimsey Took Her: Critical Essays on the Work of Dorothy L. Sayers (Kent State UP, OH, 1979). |

| ⇧12 | Sayers herself is quite clear that it is contrary to any such thing: see again her letters (as n.3) 36. |