Robin Alington Maguire

The following quotation comes from Publius Vegetius Renatus, a Roman writer of the 4th or early 5th century AD:

The legion owes its success to its arms and machines, as well as to the number and bravery of its soldiers. In the first place every century has a ballista mounted on a carriage drawn by mules and served by a mess, i.e. by ten men from the century to which it belongs. The larger these engines are, the greater distance they carry and with the greater force. They are used not only to defend the entrenchments of camps, but are also placed in the field in the rear of the heavy armed infantry. And such is the violence with which they throw the darts that neither the cuirasses of the horse nor shields of the foot can resist them. The number of these engines in a legion is fifty-five. Besides these are ten onagri (wild asses), one for each cohort; they are drawn ready-armed on carriages by oxen; in case of an attack, they defend the works of the camp by throwing stones as the ballistae do darts.[1]

Most people with an interest in Roman history are familiar with the characteristic personal weapons of the Roman legionary – the gladius, a short sword designed for stabbing or hacking, and the pilum, a two-metre-long javelin with a barbed point at the tip of a long thin metal shank.

It is less often appreciated that throughout the centuries of Roman might, the standard equipment of every legion also included over fifty powerful catapult artillery pieces.

Catapult artillery was first developed by Greek engineers during the 4th century BC. It became standard equipment in the Roman army throughout the centuries of Rome’s rise and fall. Over the centuries, engineers arrived at optimal designs for different types of catapult and developed mathematical design processes to achieve the optimum match between size of projectile and size of catapult.

We know a great deal about the workings of ancient artillery, firstly because of ancient technical treatises written between about 250 BC and AD 100 which have come down to us largely intact, and secondly because of the work of people who have puzzled out the missing pieces of information by building successful reconstructions over the last century or so.

Development

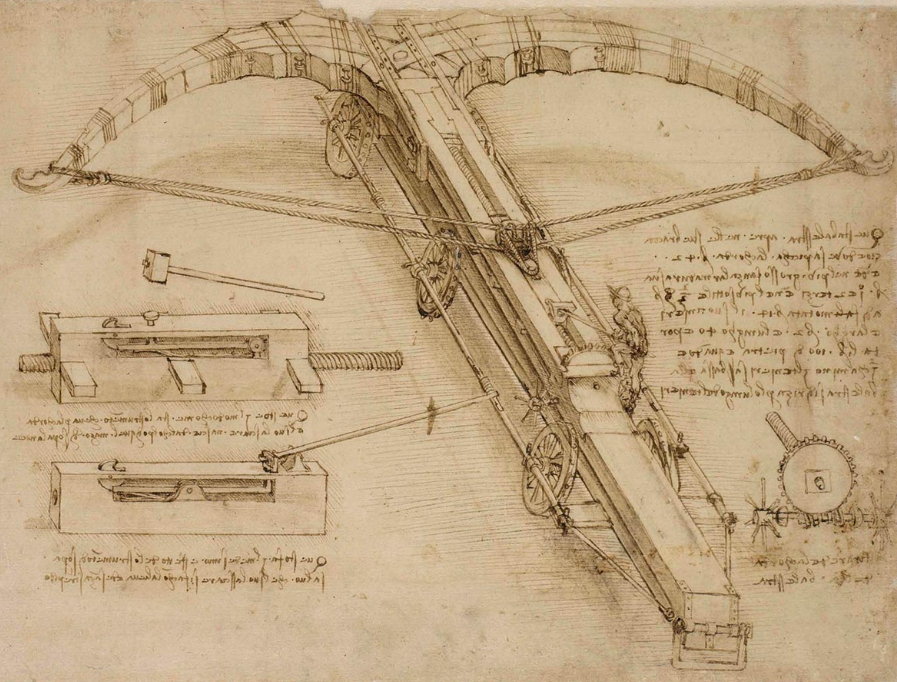

The first step in the development of effective artillery was to construct a more powerful version of the handheld compound bow famously used by the horseborne warriors of the Scythian lands to the north and east of the Black Sea. The new weapon, known as a gastrophetes, could not be drawn back by the unaided strength of the archer, so a wooden stock was attached to the middle of the bow along which ran a wooden slider connected to the bowstring. The archer could then use his full weight to force the slider to the rear, thus drawing back the bowstring so the bow was ready to fire. The arrow was placed on top of the slider. When the bow string was released by a trigger mechanism it propelled the arrow to the target. The effective range was about 200 to 250 metres. This development occurred in the (Greek) Sicilian city of Syracuse under King Dionysius around 400 BC.

The next crucial development came with the invention of the torsion spring, probably under Philip II of Macedon (father of Alexander the Great) around 350 BC. This was a skein of rope wrapped very tightly around brackets at the top and bottom of a stout wooden frame. The new catapult had two such torsion springs, one at each side, through which were inserted two rigid arms of wood connected by a bowstring. When the bowstring was drawn back (by a winch mechanism), the movement of the arms twisted the torsion springs. The stock, slider and trigger mechanism were much as before. So the torsion spring catapult stored energy by twisting the torsion spring, as opposed to a traditional bow where the energy was stored in the flexure of the bow itself. This arrangement formed the basis of all catapult design until late in the Roman period.

Torsion springs could be made from any kind of elastic (stretchy) rope, but the best material was derived from animal tendons – the sinews which connect muscles to bones. This could be taken from any animal other than pigs. On occasion, women’s long hair was used instead; it worked quite well if it had previously been kept well nourished with olive oil.

Torsion spring catapults were to be the basis of all military artillery for many hundreds of years and were still in use in the defence of Byzantium against Ottoman forces in 1050.

Ancient catapults fell into two main categories – arrow-firers and stone-throwers. Arrow-firers were mainly used as anti-personnel weapons and were aimed directly at the target: direct-fire weapons in modern terms. Stone-throwers threw heavy stone balls, usually in a high trajectory – in other words indirect fire. They were initially used in siege warfare to destroy walls and buildings, but a heavy rock propelled at high speed also made a formidable antipersonnel weapon as it bounced along the ground after landing. A typical stone projectile would weigh up to one talent or about 26 kilograms, but some catapults fired stones as heavy as three talents; one account even tells of a ten-talent catapult built by Archimedes, whose projectiles would have weighed over a quarter of a tonne.

Stone-throwers were generally a good deal larger than arrow-firers but employed much the same design of mechanism, with the projectile propelled by a small sling at the middle of the bowstring.

Catapults in the Roman army

Every time we read of a battle involving a Roman legion, we should assume that the legion made use of its complement of catapult artillery, although this aspect of warfare tends to receive less attention than it deserves in both ancient and modern accounts.

Roman legions carried catapults at the rate of one catapult for every eighty-man century. Each cohort (of six centuries) had one stone-thrower and five arrow-firers. Their crews were skilled specialists who were granted the valuable status of “immunes” – that is to say, they were exempt from tiresome routine tasks such as guard duty. Although the terminology altered somewhat over time, the term ballista was commonly used to describe any two-armed torsion spring catapult in Roman service.

Arrow-firer catapults

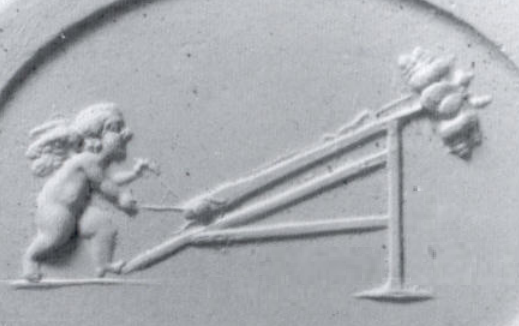

Until around AD 100, Roman arrow-firers followed the design inherited from the Greeks, with the two torsion springs built into a heavy timber frame, as shown in the picture of the scorpio above. Its name, meaning “scorpion”, is no doubt due to its fearsome “sting”.

The size of arrow-firer was described by stating the length of arrow it fired. A ‘three span’ projectile was 70cm long, weighing some 200 grams. It was made of wood with a steel tip and might carry small stabilising flights made of wood or leather

The wooden frame might be fitted with a plate of armour on its front face. The catapult mechanism was mounted on a wooden stand by means of a universal joint which enabled the operator to aim the weapon. Arrow-firers had a two man crew in battle, just like modern infantry support weapons. We can presume that the senior of these was the gunner who aimed and fired the weapon, while his loader would have winched back the mechanism between shots and loaded the arrows. This catapult would have been just about portable over moderate distances, weighing some 60kg, with one man carrying the catapult mechanism itself and the other the support stand.

While the armour and timberwork would have provided the crew with some limited protection against enemy fire, they also prevented the gunner from being able to sight freely along the line of fire and aim at his target – a definite disadvantage in a direct-fire weapon.

From about the time of the emperor Trajan’s Dacian campaign at the very end of the 1st century AD, the Romans adopted a more sophisticated design with metal rather than timber frames which gave the gunner a very much better view of the target. The torsion springs are enclosed in metal cases giving protection against damage or foul weather. This was called the cheiroballistra or “hand catapult”.

The circular arch shape in the middle of the top cross piece confers no structural benefit and must have been included to help the gunner sight onto his target. Such a sighting device should not be regarded as primitive: even at Olympic level today, the shotguns used for clay target events will typically carry sights consisting of just two metal pinheads atop the barrels. Devices like this cheiroballista remained in use for over nine centuries.

At about the same time the Romans began mounting the new arrow-firers on small carts drawn by mules, thus improving mobility and ensuring that they could be brought into action at a moment’s notice, even on the march, generally firing from a position behind their own infantry. This version was called the carroballista, or “cart catapult”.

In this image it looks as if the gunner is firing forwards on the move. This must be a case of artistic licence: there would have been a grave risk of hitting one of the mules if it tossed its head at the wrong moment. In reality, the catapult must have been fired over the side or rear of the cart. I also feel sure that Roman gunners, like today’s tank gunners when crewed on vehicles with unstabilised weapons, were taught never to fire on the move over the heads of their own troops, as any sudden unevenness in the ground might cause the vehicle to tilt and the missile to hit their own side.

We find a vivid testament to the reliability and accuracy of Roman arrow-firers in Caesar’s account of his Gallic Wars. In 52 BC, he besieged the city of Avaricum (near modern Bourges in central France). The defenders resisted fiercely, at one point setting fire to Caesar’s siege works. As Caesar recounts,

there happened in my own view a circumstance which, having appeared to be worthy of record, we thought it ought not to be omitted. A certain Gaul before the gate of the town, who was casting into the fire opposite the turret balls of tallow and fire which were passed along to him, was pierced with a dart on the right side and fell dead. One of those next to him stepped over him as he lay, and discharged the same office: when the second man was slain in the same manner by a wound from a cross-bow, a third succeeded him, and a fourth succeeded the third: nor was this post left vacant by the besieged, until, after the fire of the mound was extinguished and the enemy repulsed in every direction, an end was put to the fighting.[2]

In Caesar’s original Latin, the “cross-bow” is a scorpio arrow-firer.

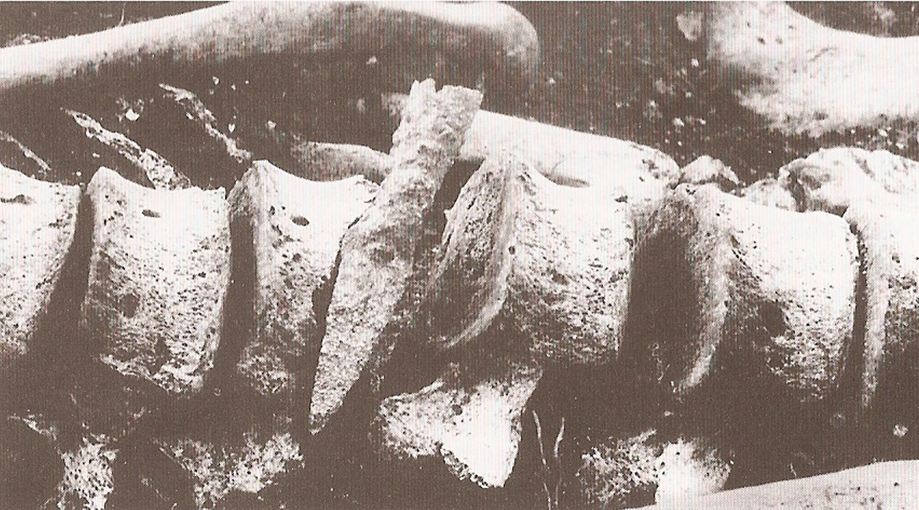

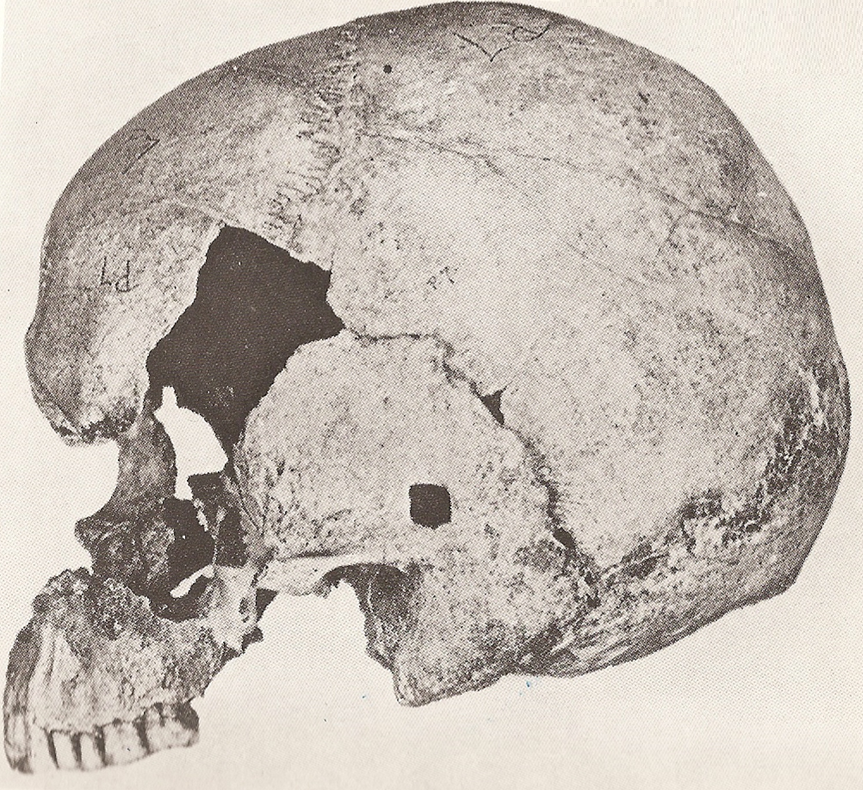

During the conquest of Britain under the emperor Claudius in AD 43, the 2nd Legion was commanded by the future Emperor Titus Flavius Vespasianus (AD 9–79). We have vivid evidence of the effect of his arrow-firing artillery at the siege of a major enemy fortress now known as Maiden Castle, near Dorchester in southern England.

When excavated in the 1930s, two skeletons bore testament to the effect of these weapons:

Evidence was also found that at some stage Vespasian had successfully concentrated his artillery fire on a particular hut within another nearby fortification, possibly used as a meeting point by British chieftains. Eleven bolt heads from arrow-firers fired at a range of about 150 to 170 metres were found concentrated in a ten-metre circle within the perimeter of the hut.

Arrow-firers had a maximum range of around 500 metres, more than twice as far as a handheld compound bow. In one exceptional case a range of 650m was claimed. The power of course came not from stored chemical energy, as in modern firearms, but from the human muscle power of the loader winding back the mechanism before each shot. This was not a great constraint on performance, though. At the maximum rate of fire – perhaps three or four shots per minute – the loader’s workload would have been roughly equivalent to walking steadily up a staircase, a performance which could be kept up for hours.

Arrow projectiles were sometimes visible in flight. The following account comes from Dr Eric Marsden, who carried out very extensive work on Greek and Roman artillery in the mid-20th century:

If one stood directly behind a 25-pounder (the standard British field-artillery in the Second World War) one could just glimpse the shell as it travelled along the early part of its trajectory. In the case of my full-scale model of a three-span arrow-firer, it is not too difficult to follow the bolt along its whole path, provided that one stands directly behind the machine. It is, in fact, a little harder to follow than a well-driven golf-ball. But, when an observer stands even slightly to one side, he just gets the impression of blurred movement in front of the machine as the trigger is pulled, and it is impossible to follow the bolt’s flight.[3]

Stone-thrower catapults

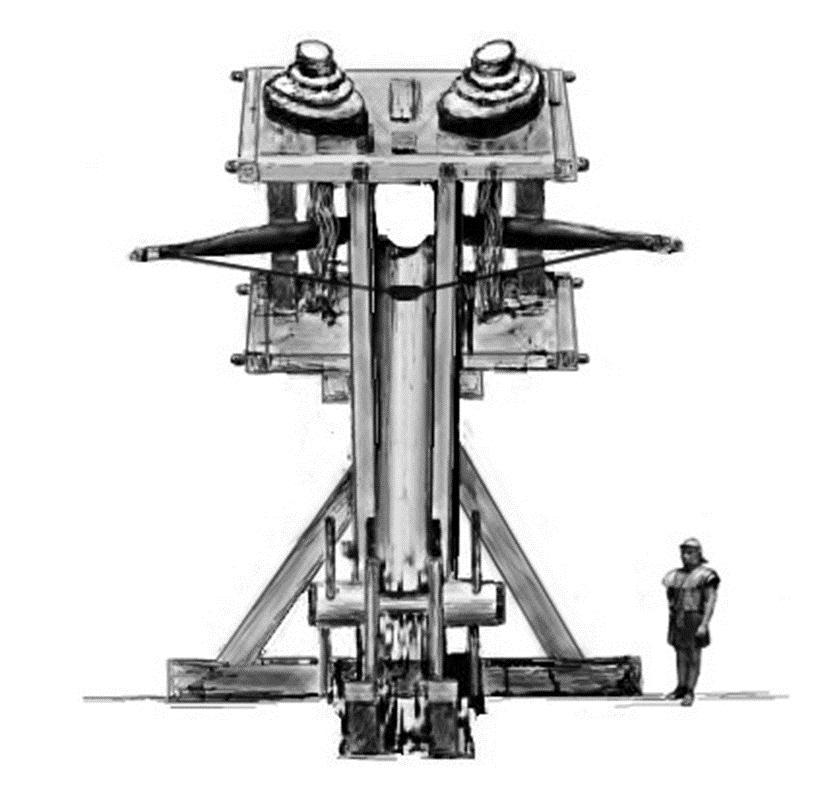

Until some time in the 4th century AD, the stone-thrower used by the Roman army was a larger version of the arrow-firer described above, often firing a one-talent (26 kg) projectile. A faithful modern reconstruction of such a machine weighed ten tons; the original must have been powered by over half a tonne of sinew rope.

In the design manuals which have come down to us, this was typically a large and elaborate structure, occupying about the same space as a fairly compact house of two or three storeys. It was not mobile, and therefore had to be assembled in its firing position. There is no evidence of stone-throwers of this kind ever being fitted with wheels.

According to one theory, the legions would have carried kits of metal parts and torsion spring ropes, and combined these with timber sourced locally to build a stone-throwing catapult when and where needed. This would have been satisfactory in static settings such as siege warfare, but restricted the usefulness of stone-throwers as field artillery.

This type of stone-thrower had a maximum range of perhaps 200m to the first bounce; the stone might travel up to 370m in all. Even after the first bounce, a 26kg stone must have remained highly lethal against infantry. Designers of defensive fortifications were advised that a city wall had to be at least three metres thick to resist bombardment, and that outer defences such as ditches should be used to try to keep stone-throwers at least 160 metres away from the walls.

I have always found it difficult to imagine how the Romans could have made practical use of such a large and complicated machine in the brutal business of siege warfare. Apart from anything else, it would often have been vulnerable to continual return fire from the defenders’ own catapult artillery. The answer may lie in a modern reconstruction at Hjemsted in Denmark, which amounts to a heavy catapult stripped down to its minimum essential components.

It is not hard to imagine this device being rapidly erected in the required position, the individual components having been fabricated and partially assembled away from the battlefield. It consists of the basic firing mechanism, with the supporting framework kept to a minimum. It would not have been easy to swivel onto a new target, but this would not have mattered if its job was to batter away at one section of a city wall until it made a breach, And with its low height such a device would have been easy to protect against direct enemy counter fire by erecting a bank of earth immediately in front of it. At the end of a long siege I think the attackers’ catapults might have looked much like this reconstruction.

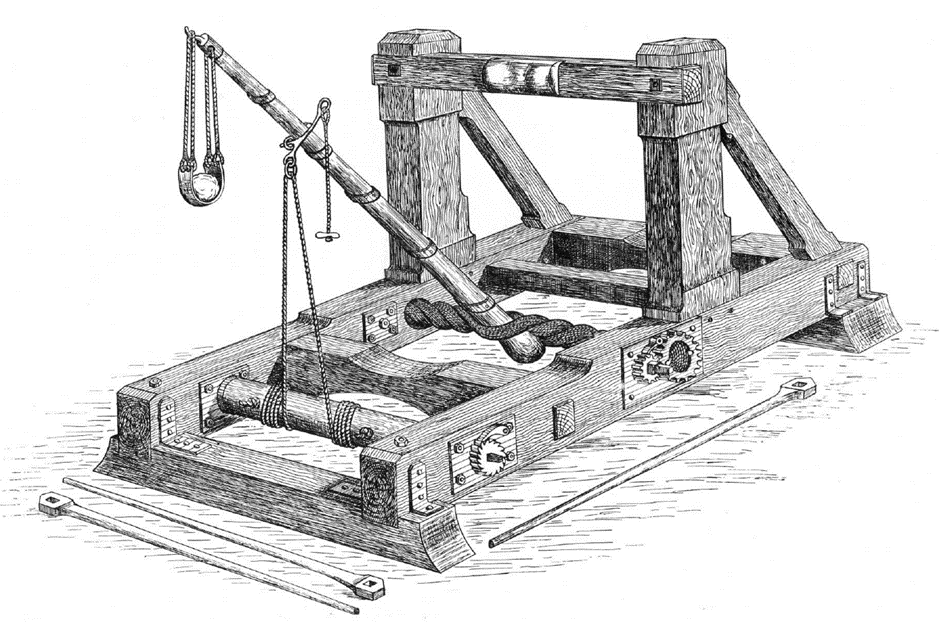

In the later Roman Empire, the two-armed stone-thrower shown above was replaced by the onager, a significantly simpler device. The earliest definite mention dates to AD 353.

The onager is powered by a single large torsion spring, which drives a single swinging arm. On discharge, the projectile is launched from the sling at the end of the arm (which effectively gives the arm extra length without adding weight). At the end of its travel the arm slams into a padded wooden buffer which gives the weapon a tremendous “kick” – hence presumably the name, an onager being a wild ass.

So powerful was the kick or recoil that if placed on a rigid surface of brick or stone, the onager would quickly reduce this to rubble. It was necessary to place it on the ground, or on a resilient platform of turf. For this reason, I suspect that modern depictions showing onagers on the decks of Roman warships are inaccurate, as it would soon have shaken the hull to bits. Unlike its predecessor, the onager could be transported fully assembled, as indicated by the extract from Vegetius at the start of this article. It had an impressive range of up to 500m.

Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman soldier and historian of the late 4th century AD, wrote a history of the Roman empire of which the later books survive. In recounting the campaigns in which he himself took part, he includes many accounts of the use of catapult artillery, by both the Romans and their enemies. It is worth pointing out that in contrast to earlier usage, Ammianus generally refers to the arrow-firer as a ballista and to the stone-throwing onager as a scorpio. At one point during a campaign against Rome’s inveterate enemies, the Parthians, in what is now Iraq he witnesses an incident which testifies to the fearsome power of the onager.

In the course of these contests an engineer on our side, whose name I do not recall, happened to be standing behind a scorpion, when a stone which one of the gunners had fitted insecurely to the sling was hurled backward. The unfortunate man was thrown on his back with his breast crushed, and killed; and his limbs were so torn asunder that not even parts of his whole body could be identified.[4]

Projectiles from stone-throwers flew with a loud whizzing sound and were visible in flight. At the siege of the mountaintop fortress of Masada in AD 74, the Jewish defenders could see incoming projectiles of white limestone silhouetted against the darker ground below, and give warning to take cover. The Romans responded by painting the projectiles black before firing.

In a modern experiment, it took a professional sculptor two and a half days to carve a one talent (26kg) spherical rock.

Uses of catapult artillery

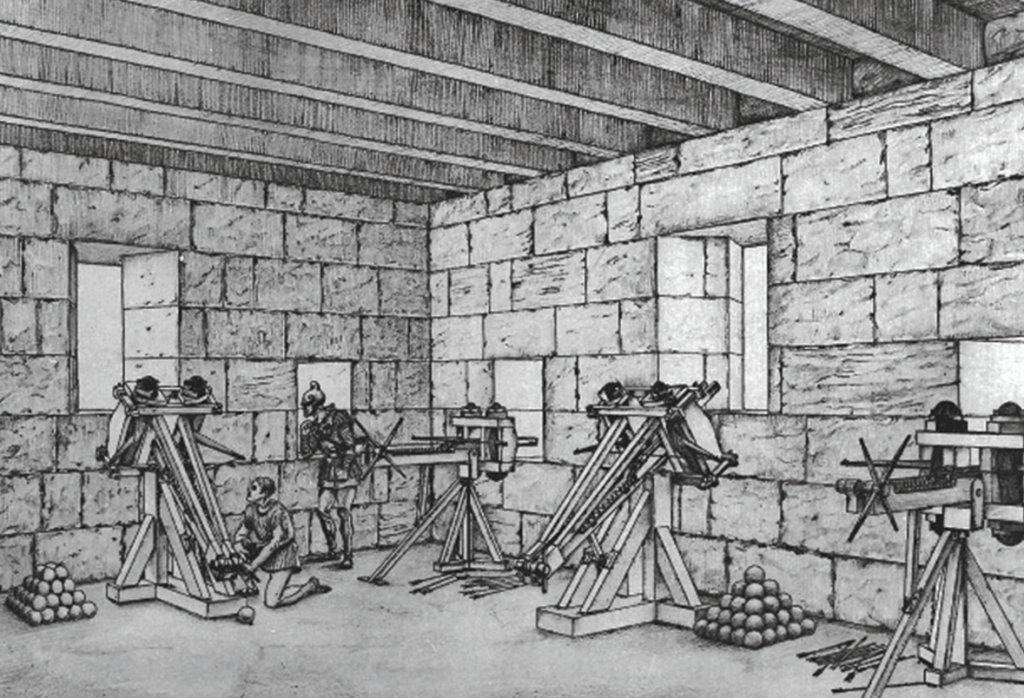

Catapults were used to defend cities as well as attack them. Just before the Third Punic War in 146 BC, the city of Carthage agreed to disarm in the hope of avoiding destruction and some two thousand catapults were taken down from the walls of Carthage and handed over. The picture below shows the conjectured interior of a defensive artillery tower in a Hellenistic city:

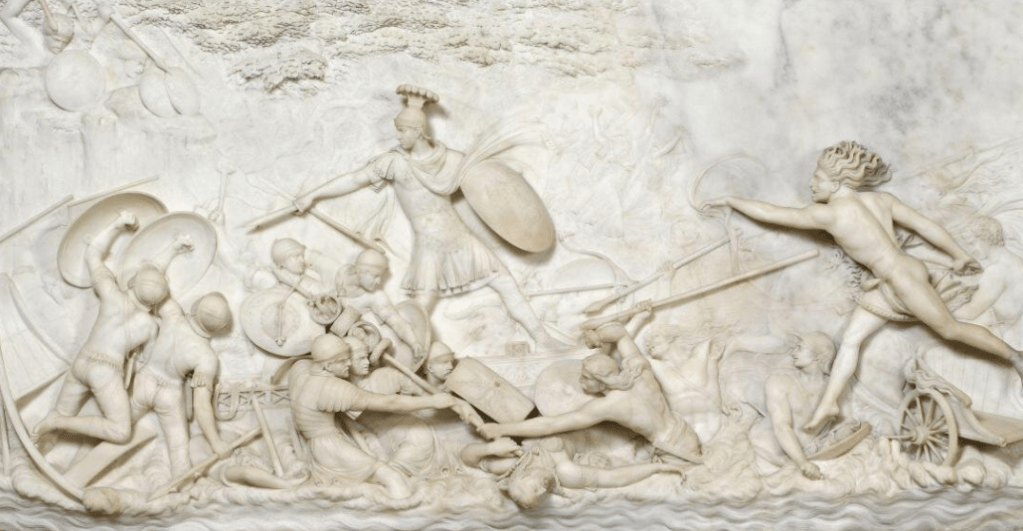

It would seem that catapult artillery was first used in siege warfare, where its lack of mobility mattered little. Alexander the Great was one of the first to use catapults as field artillery to support his opposed crossing of the River Jaxartes (now the Syr Darya) in Central Asia in 329 BC. Siting his artillery safely on the hither bank, Alexander used it to bombard his enemies, fierce nomad horsemen of Scythia, so driving them back and enabling his infantry to land.

In AD 134 the soldier and writer Lucius Flavianus Arrianus (Arrian, c.86–160), then governor of Cappadocia, faced battle with another powerful army of Scythians from the Alan tribe. His work Acies contra Alanos (Array against the Alans) has come down to us in part and seems to contain a transcript of his actual written orders to his subordinate commanders for the conduct of the impending battle. He would use his catapult artillery as part of a dense hail of every kind of missile, to be loosed against the enemy as they charged:

Once thus arrayed there should be silence until the enemies come within missile range; when in range the loudest and most intimidating war cry must be raised by the whole lot, and bolts and stones must be fired from the artillery pieces and arrows from the bows, and javelins by both light armed and shield bearing javelinmen. Stones must also be thrown at the enemies by the allied force on the overwatch position, and the whole missile rain must come from all sides to make it concentrated enough to panic the horses and destroy the enemies. And the expectation is that the Scythians will not get close to the infantry battle formation because of the tremendous weight of missiles.[5]

Catapults were mounted on warships, often on towers erected on the foredeck. When Julius Caesar mounted his first raid into Britain in 55 BC he had to use his naval artillery to drive hostile Britons back from the shore before his troops could land.

Ammunition

Catapults mostly fired arrows or stones, but other types of ammunition were sometimes used. The Carthaginian general Hannibal (247–c.182 BC) is famous for leading an army equipped with elephants across the Alps during the second Punic war against Rome (218–201 BC). After the defeat of Carthage, Hannibal took service with King Prusias I of Bithynia in his war against King Eumenes II of Pergamon. Bithynian warships commanded by Hannibal were equipped with stone-throwers and in sea battles were sometimes used to fire clay pots at enemy vessels. The Pergamene sailors’ derision on seeing this was soon changed to alarm when the pots landed on board, broke open and proved to be filled with poisonous snakes. On other occasions, pots filled with scorpions achieved a similar effect. Flaming incendiary projectiles could be fired either from arrow-firers or from stone-throwers.

Modern reconstructions

In modern times there have been numerous attempts to reconstruct the catapults of the ancient world using detailed descriptions which have survived from Greek and Roman times. One of the pioneers of modern reconstruction was General Erwin Schramm of the German army, who built both arrow-firers and stone-throwers in the early 1900s. He found that an arrow-firer could be reliably aimed and fired to hit a man-sized target at a range of at least 100 metres. This is a much better performance than a musket of the early 19th century, from which a single shot could not be relied on to hit anything smaller than a large barn door at such a range.

On 16 June 1906, Kaiser Wilhelm II attended one of von Schramm’s firing demonstrations, as shown in the photograph below where he stands next to a one-talent (26kg) stone-thrower. This event nearly changed history. Before one shot the stone-thrower was loaded incorrectly, with the bowstring positioned too low behind the projectile – an occupational hazard with stone-throwers. On firing, the bowstring was pulled under the rock, flipping it high in the air; on landing it narrowly missed the Kaiser. One is reminded of the similar accident recounted above by Ammianus Marcellinus.

Artillery design manuals

The basic design of two-armed catapult artillery remained largely unchanged for over a thousand years. Over this time, enormous numbers were constructed and by trial and error the exact design was optimised to a high degree. We have several Greek and Roman design manuals which specify the form and dimensions of each component in precise detail. Dimensions are typically given as multiples of the torsion spring diameter which is used as the basic measure of a catapult’s power

The surviving artillery manuals were written by four experts: Biton of Pergamum (2nd/3rd cent. BC); Philon of Byzantium (280–220 BC); Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (c.75–after 15 BC) (he was a professional artillery officer under Julius Caesar); and Heron of Alexandria (mid-1st cent. AD).

Matching catapult size to projectile size

In the artillery manuals we encounter uniform rules for finding the optimum dimensions of catapult to match the intended size of projectile. For arrow-firers the rule was simple. The torsion spring diameter should equal one ninth of the intended length of arrow; this of course presumes a standard shape of arrow.

For stone-throwers a more complex equation was developed:

D = 1.1 x ∛(100 W)

where W is the weight of the stone projectile in mina (0.436kg) and D is the diameter of the torsion spring in dactyls (19.268mm).

The equation asserts that, for optimum performance, the diameter of the torsion spring should be in a fixed proportion to the cube root of the weight of the projectile. This amounts to saying that the volume of the torsion spring (in effect, the propulsive power of the device) should bear a fixed proportion to the weight of the projectile. This seems like a pretty reasonable proposition. So for a one-talent (26.2kg, 60 mina) projectile, the ideal catapult should have a torsion spring diameter of 20 dactyls (385mm).

Because the dimensions of the catapult were proportional to the cube root of the projectile weight, this meant that a large increase in payload weight required only a modest increase in size, Thus, Archimedes’ monstrous ten-talent catapult would have been only a little more than twice the overall size of the one-talent machine.

The design equation for stone-throwers is the first known practical use of the cube root in history. However, the Greeks did not possess any of our modern methods for finding cube roots. Instead, they used the theorem of two mean proportionals, which is explained in the Appendix below.

Later developments

To conclude, it may be helpful to point out the key difference between the catapult artillery of the classical period and the later medieval models. Greek and Roman catapult artillery relied on energy stored in torsion springs. By contrast, many of the later medieval equivalents, such as the trebuchet or mangonel, were constructed like see-saws, with a heavy counterweight at one end causing the other end to swing upwards and fling a solid projectile. The counterweight might consist of a heavy rock, or its place might be supplied by a group of men pulling down simultaneously on ropes. This approach did not allow for the precise aiming of the ancient arrow-firers, but the medieval machines had the virtue of being quick and easy to construct.

Robin Alington Maguire is a former civil engineer and banker with a longstanding interest in ancient history and culture who likes to seek out new deductions from fragmentary ancient sources. He has translated and edited Napoleon Bonaparte’s Commentaries on the Wars of Julius Caesar (Pen & Sword Books, Barnsley, 2018). His earlier essays for Antigone argued that Cicero should have taken a different tack during the Catilinarian Conspiracy of 63 BC, reconstructed the rations supplied to the crews of Athenian trireme warships, examined Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon, and delved into submarine springs of antiquity.

Further reading

Ammianus Marcellinus is well worth reading, not only for his military insights but for a vivid sense of the decaying Roman empire in the final decades before the collapse of its western element, a time when the mighty city of Rome itself had dwindled to little more than a quaint tourist attraction. His Latin text and an English translation can be found here.

Vitruvius’ work on catapults is contained in his great work On Architecture, written during the reign of Augustus (27 BC–AD 14). See especially Book 10, chapters 10–12, whose text can be found here.

In the 1960s, E.W. Marsden carried out definitive work on the surviving artillery manuals from antiquity. His work was drawn together in two volumes.

Greek and Roman Artillery Historical Development (Oxford UP, 1969). This describes the history, construction and use of catapult artillery in great detail.

Greek and Roman Artillery Technical Treatises (Oxford UP, 1971). This contains the text (in the original and in English) of the surviving manuals of Heron, Biton, Philon and Vitruvius, together with discussion of later Roman arrow-firers and the onager stone-thrower.

Roman Imperial Artillery by Alan Wilkins (3rd ed., Archaeopress Archaeology 2024) gives a detailed but accessible account of Roman catapult artillery. Wilkins shows that much is still being discovered about the construction and performance of the catapult artillery of antiquity, with new archaeological findings going hand in hand with the results obtained from painstaking modern reconstructions of the ancient machines.

As always, the ancient accounts are all well worth reading, and are readily accessible online.

Appendix: The theorem of two mean proportionals

Philon of Byzantium came up with an elegant if convoluted means of extracting cube roots so as to permit designers to arrive at the optimum spring diameter D for a given weight of projectile W. It was based on his contribution to a conundrum which had exercised the minds of Greek thinkers since around 400 BC, sparked by a typically opaque pronouncement by the Delphic Oracle. It was known as the Delian Problem, or Doubling the Cube, and it essentially involved finding a way to arrive precisely at the cube root of two, ∛2. It is of course easy to come up with an approximate answer, but for Greek philosophers, precision mattered.

At the time this problem was at the cutting edge of mathematical enquiry, and caused some discomfort to Greek philosophers as they realised that they were unable to express the cube root of 2 as a rational number, that is to say one whole number divided by another. They seem to have greeted the discovery of non-rational-number cube roots with the same horrified amazement with which a modern student might react to the square root of minus one.

By Philon’s time it was appreciated that a good way of attacking the cube root problem was through the theorem of two mean proportionals. To explain what this means, if in a series of four numbers a, b, c and d each successive number stands in the same proportion to the preceding number, then the two intermediate numbers b and c are the “two mean proportionals” of the smallest and largest numbers a and d.

So, for example, 6 and 12 are the two mean proportionals of 3 and 24 because 6/3 = 12/6 = 24/12. Or, more generally, b/a = c/b = d/c.

Cube roots come into it because it is easy to show that

b = ∛(a2d) and c = ∛(ad2)

So if a = 1 and d = 2, then b will equal the long-sought cube root of 2.

Philon’s solution, set out in his artillery manual, involves drawing a diagram based on measurements equal to a and d. Lengths equal to b and c can then be measured off.

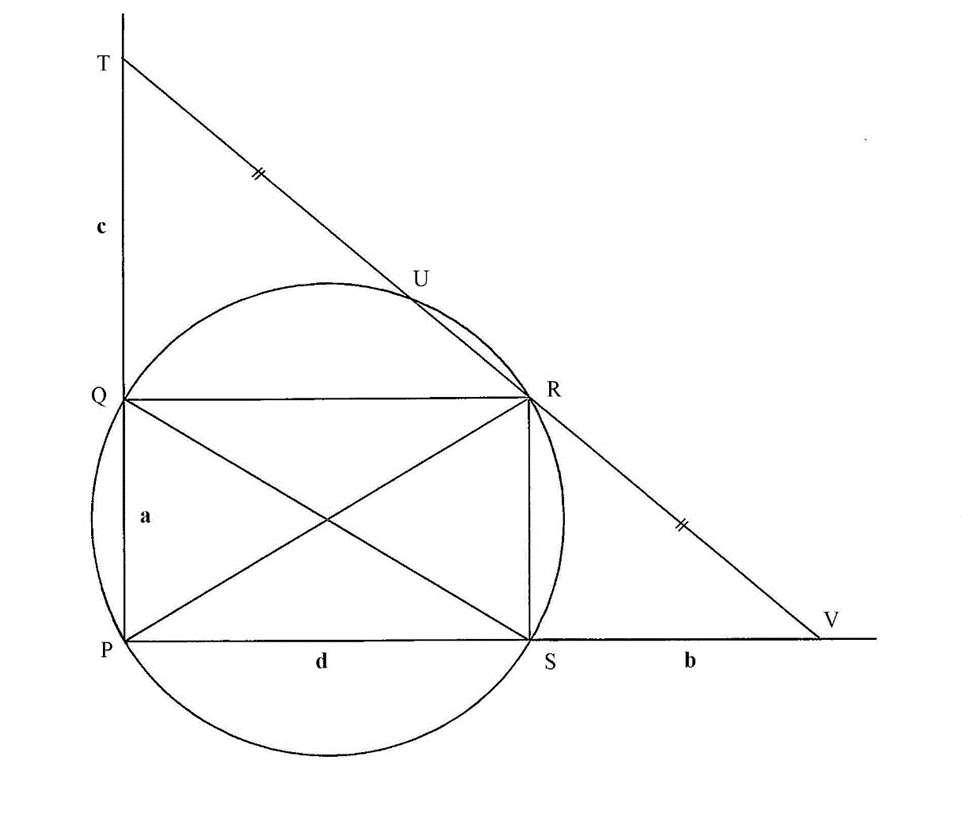

Here is the diagram:

To construct the diagram, two perpendicular axes are drawn, meeting at P. Between them is added a rectangle PQRS, with sides equal in length to a and d. Diagonals are drawn between the corners of the rectangle. Next a circle is added, centred on the point where the diagonals meet and passing through the four corners.

The final step is to add line TV which runs between the two axes and passes through R. TV must be positioned such that the two segments which lie outside the circle – TU and RV – are of equal length. Finding the right position involves some juggling with straight edge and dividers. Then it is just a matter of measuring the length of SV, which equals b, and that of QT, which equals c.

This seems a bit like black magic: it is far from obvious that SV and QT have the values claimed for them. However, the same approach, with one slight variation, is presented in the later artillery manual of Heron of Alexandria. He was sufficiently proud of the technique as to include a mathematical proof. In the version which has come down to us, a few lines of the proof are missing, but it is not difficult to reconstruct them and confirm that the diagram, if accurately drawn, will indeed yield exact values of b and c as advertised.

Heron wrote some 300 years after Philon, which shows how torsion spring catapults were an absolutely standard item of military equipment for hundreds of years.

Returning to the stonethrower equation D = 1.1 x ∛(100W)

How do we use Philon’s technique to solve the equation and find the correct torsion spring diameter for a given weight of projectile? The simplest approach is to choose two numbers a and d such that

a2d = 100W

So if W = 20 mina, 100W is 2,000 and one might choose a = 10 and d = 20. Having drawn Heron’s diagram using these dimensions, we just measure the length of line SV. As explained above,

SV = b = ∛(a2d) = ∛(100W)

So it is then easy to calculate the torsion spring diameter D = 1.1 x b.

(If W is 20 mina, D should equal 13.9 dactyls.)

Notes

| ⇧1 | Publius Vegetius Renatus, De Re Militari Book 2, trans. Lt. John Clarke (1767). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Caesar, Gallic War 7.25, trans. M. Alexander, 1869. |

| ⇧3 | Marsden, Technical Treatises, 240. |

| ⇧4 | Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae 24.4.28. |

| ⇧5 | Arrian, Acies contra Alanos, English version here (trans. S van Dorst). |