Anatoly Grablevsky

It is a truth universally acknowledged that all historical empires have an expiration date. The Assyrian Empire fell when its capital, Nineveh, was sacked by the combined forces of Medes and Babylonians in 612 BC. The Persian Empire of Darius III fell when it was conquered by Alexander the Great in 330 BC; even its great successor, the Sassanian Empire, fell with its last king, Yazdegerd III, to the armies of the Arab Caliphate in AD 651.

More recent imperial formations all have well-known death dates: for example, the Aztecs’ regional hegemony in the New World (d. 1521); the millennia-old Middle Kingdom of China (d. 1911); or the House of Habsburg’s dynastic European empire of Austria-Hungary (d. 1918). The only major historical empire whose year of death is still disputed is Rome. Some even say that the empire never died at all, but lives on in various forms until the present – imperium sine fine indeed.

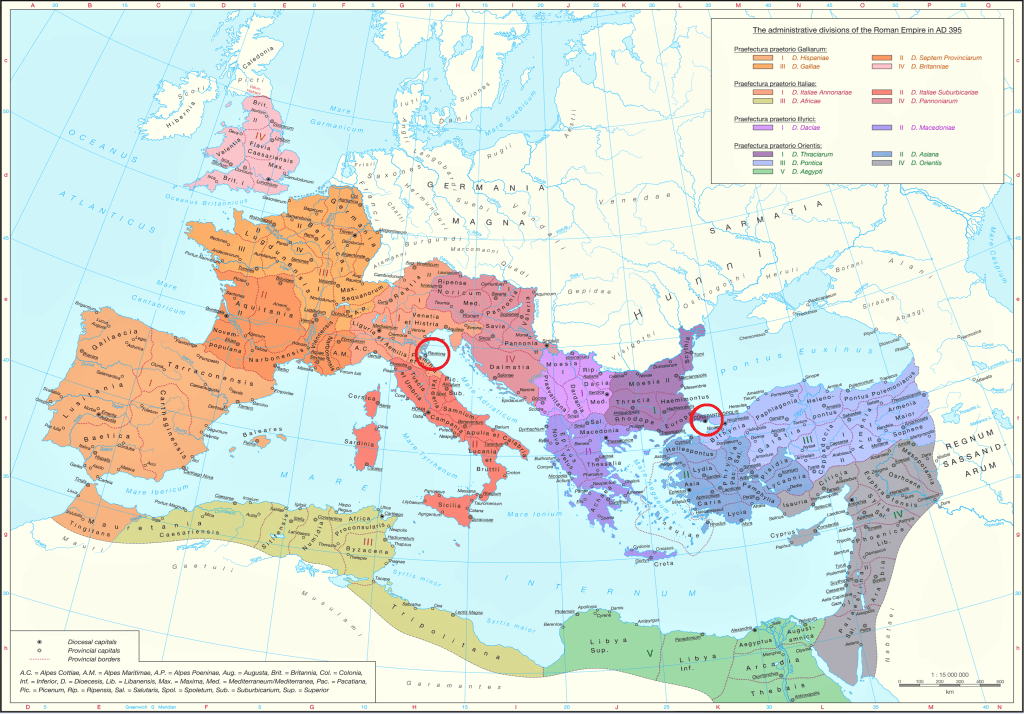

The question of how and why Rome declined and fell is complex and well-trodden, while also being intimately tied into debates about the nature of empire, migration and indeed European and Western identity. To avoid getting lost in this morass, my aim is more limited: to provide the Roman Empire with a dignified death certificate, clearly stating the time and place of its demise. Since from AD 395 onwards the Roman Empire was divided into two independent entities, we will look at events and years affecting both the Western and Eastern halves of the Roman Empire.

There are three traditional contenders vying for the prize of being the Roman Empire’s demise, separated by almost a millennium: the fan favorite is AD 410 the returning champion is 476; and the runner-up is 1453. Since empires before and after Rome have ended in years of political, military or symbolic defeat (and usually a mix of all three),[1] we will examine each one of these years in turn, using the following criteria to evaluate their suitability:

1. the year must involve (geo)political catastrophe, such as a significant loss of territory and/or political support that cripples the central authority and power of the Empire;

2. the year must feature military catastrophe, such as a defeat in the field that cripples the army and the resources of the Empire;

3. the year must be marked by a symbolic catastrophe (for example, the loss of a capital city or powerful figurehead) that cripples the idea of, and belief in, the empire as a cohesive, majestic whole in the minds of its subjects.

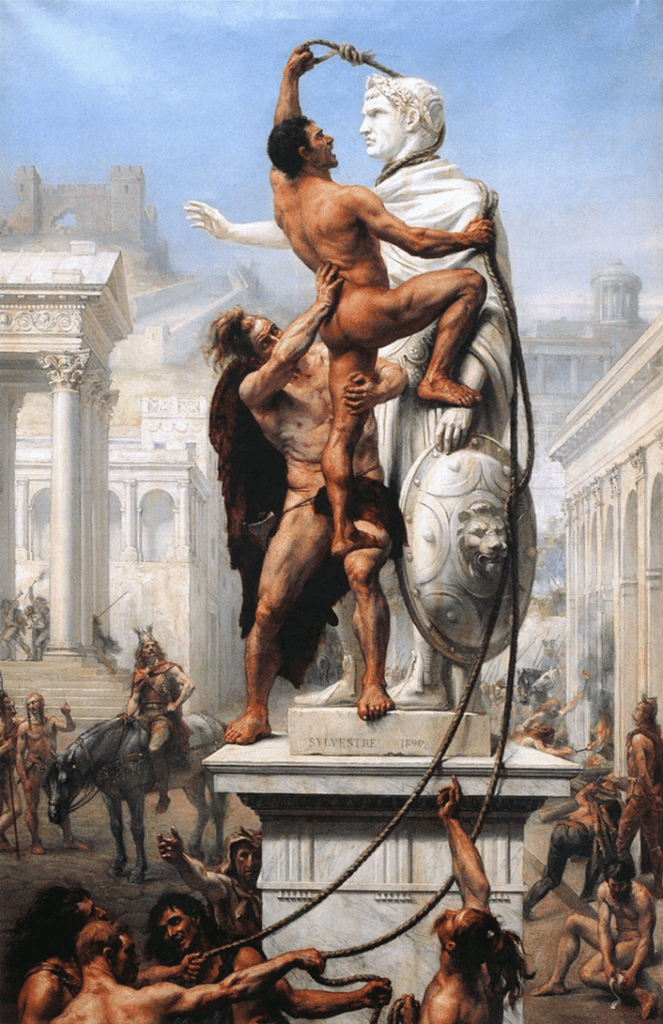

410: The Sack of Rome

On 24 August, 410, for the first time in 800 years, the city of Rome was sacked by an army of Goths who were led by their king, Alaric. Rome, the city, had fallen.

The scenes that unfolded in the Eternal City shocked contemporaries. St Jerome, for instance, was horrified: “My voice sticks in my throat; and, as I dictate, sobs choke my utterance. The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken.”[2] Jerome then goes on to quote some lines from Virgil’s Aeneid (2.361–5), on the Fall of Troy, which he has doctored so as to remove any pagan connotations:

Quis cladem illius noctis, quis funera fando

explicet aut possit lacrimis aequare dolorem?

urbs antiqua ruit multos dominata per annos

plurima perque vias sparguntur inertia passim

corpora perque domos, et plurima mortis imago.[3]

Who can tell that night of havoc, who can shed enough of tears for those deaths? The ancient city that for many a hundred years ruled the world comes down in ruin: corpses lie in every street and men’s eyes in every household death in countless phases meet.[4]

The most consequential reaction to the sack was that of St Augustine. As he explained seventeen years later in his Retractions (2.43), Augustine wrote his magnum opus, The City of God, as a direct response to Alaric’s sack of Rome. The book was meant as much to defend Christianity against pagans, who claimed the new religion was responsible for the sack, as to comfort Christians that this calamity was not, in fact, the end of the world, quite literally.[5] Clearly, nobody missed the obvious symbolic value of events in 410, or what the sack heralded for the empire.

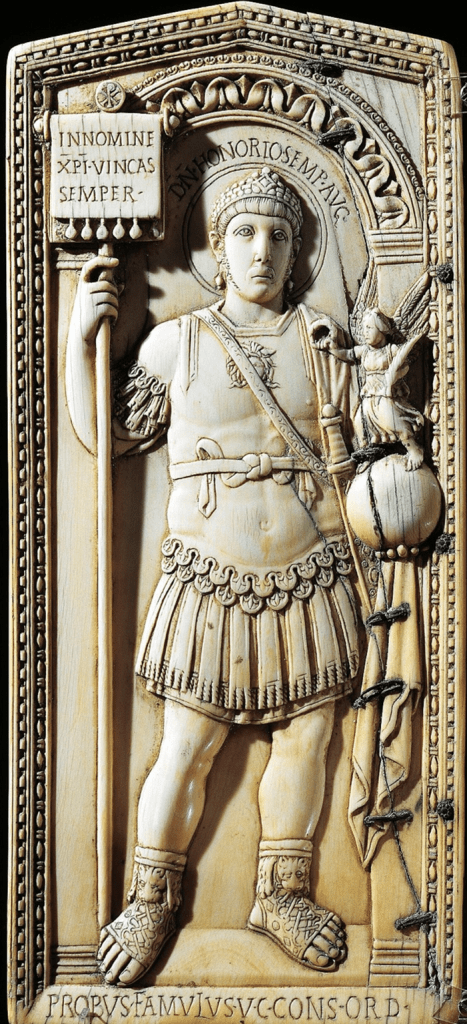

Pessimism was exacerbated by the sobering fact that the sack was the direct and entirely predictable result of a mind-bogglingly misguided, directionless and (frankly) stupid imperial policy. From 395, when the emperor Theodosius, who was then on his deathbed, divided the Empire between his two sons Honorius and Arcadius, the Western and Eastern halves of the Roman Empire spent as much effort squabbling over territory in the Balkans as they did defending themselves against roving barbarian armies.

Internal cohesion and central authority were also weakened by the fact that the emperors of both the Western and the Eastern Roman Empires (centered in Ravenna and Constantinople respectively), were either too weak or too uninterested in ruling. Real power therefore lay in the hands of powerful court generals, often themselves of barbarian extraction. The most significant, for our purposes, of these political-military commanders, was Stilicho, who was the effective power behind the Western Throne.

The biggest threat, but also the greatest opportunity, for both Western and the Eastern empires in their power games, was king Alaric’s army of Visigoths and other Germanic barbarians, which, since 395, had been raiding the Balkan provinces of both empires. While each half of the empire sought to buy off Alaric’s loyalty and use his army against the other, Alaric’s primary goals were to obtain stable monetary and grain subsidies (annona) for his people, and an official position for himself within the Roman military establishment. It is crucial to remember that, at this point, most barbarian tribes and armies did not seek to destroy or conquer the Roman Empire, but rather to live inside of it, and benefit from its resources and protection.

As long as Stilicho remained in de facto power in Ravenna, he was able to defend Italy against Alaric,[6] whom the Eastern Empire kept encouraging to attack the West. Stilicho successfully employed a carrot-and-stick strategy with the Visigothic king, defeating Alaric when he could (in 403), and paying him off with gold and titles (in 406) when Stilicho had to focus on other threats and invasions.[7]

Everything changed in 408, when, just as a permanent settlement with Alaric was in sight, Stilicho was abruptly murdered in a coup by elements of the Western Roman army who opposed Stilicho’s perceived appeasement of Alaric and other barbarian groups. Alaric was now declared an enemy of the empire. In response, the king again sought compromise and a permanent modus vivendi with Ravenna, which would include a land grant for his people in Pannonia, to live as foederati, i.e. vassals of the empire, who would defend it from invasions. Ravenna refused his demands out of hand. To compel Honorius to agree, Alaric twice besieged and threatened Rome. Again and again, Honorius and his ministers refused to compromise, or went back on their promises, even as Alaric’s offers grew more reasonable and moderate (cf. Zosimus, New History 5.51). With no deal in prospect, Alaric sacked Rome, virtually out of desperation.

As avoidable and shocking as the sack was, 410 was far from a military or even a political catastrophe. The historian Procopius famously recounts in his History of the Wars (3.2.25–6) how, when Honorius was told that Rome had perished, he was at first deeply distraught, but soon felt relief when he was informed that his pet chicken, nicknamed Rome, was in fact still alive. The anecdote, although almost certainly apocryphal, does reveal the city of Rome’s utter strategic and political insignificance by that point.[8]

Indeed, for Alaric, the sack hardly improved his position, as his Goths still desperately lacked the permanent food supply and land grant they so desperately sought. In the end, after eight years of devastating and futile warfare for both sides, the Goths finally received what they had been asking for all along: they were allowed to settle in southern France as foederati in 418. For the next thirty years, although they continued to pursue their own aggrandisement, these Visigoths would also contribute significantly to the preservation of the Western Empire, even playing a vital role in the defeat of Attila the Hun and his horde in 451.

The year 410, then, does not meet our criteria to be an annus funestus for the Roman Empire: for all its ominous symbolism, it did not lead to crippling political or military consequences. Within a decade of the fall of Rome of 410, the Western Empire was stabilised in the more capable of hands of Constantius III and Galla Placidia and relations with the Eastern Empire were greatly improved, restoring a sense of unity over much of the Roman world.

476: The Deposition of Romulus Augustulus

If you look up the end or fall of the Western Roman Empire in a general history book or online, one date keeps popping up: AD 476. The reasoning appears sound at first: it is the year when the last Emperor of the West, Romulus Augustulus, was allegedly deposed by the barbarian warlord Odoacer, who declared himself king of Italy and sent back the imperial insignia of the West to Constantinople. One can easily see why, in many popular histories,[9] the year stands in for chosen for the fall of the Western Empire: the symbolism of having the last Roman Emperor named after both the founder and first king of Rome (Romulus) and the first Emperor (Augustus), is too good. Due to his youth, Romulus would be remembered to history as Augustulus, “the little Augustus”.

However, 476 neither meets the criteria set out above for being the terminal year of the Western Roman Empire; nor does the year even factually correspond to what it claims to represent. Indeed, 476 as a diagnostic year of death is both too late and too early for the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

The year is too late, because the return of Western imperial regalia from Ravenna to Constantinople does not represent the fall of the empire, but rather a belated acknowledgement that the West no longer needed an emperor, since it now lacked an empire.[10] Indeed, rather than ending an empire, Odoacer was placing himself and Italy under the authority (even if nominal) of a single, re-united Roman Empire, ruled from Constantinople![11] The Eastern emperor Zeno not only acquiesced to the change of status, but even granted Odoacer the honorary titles of Patrician and Dux Italiae (leader of Italy), to cement the king’s status as ruling Italy on behalf of Roman Empire. This reading is supported by contemporary Italian sources,[12] where the events of 476 are barely noticed, or else simply seen as a natural progression: Odoacer is merely the latest in a long line of barbarian rulers of the West. If 476 marked no rift, this then naturally leads to the question of when that rupture actually took place, since it must have happened before 476.

On the other hand, 476 is paradoxically also too early to stand as the end of the Western Empire. The commonly held belief that Romulus Augustulus was the last emperor of the West is doubly wrong. Augustulus, who in 475 was ten years old when he was installed on the throne by his ominously-named father Orestes, was never even recognized as emperor by Zeno. The last ‘legitimate’ Western Roman Emperor from that perspective is actually Julius Nepos, who had to flee Rome and go into exile to Dalmatia in 475, but did not renounce his claim to the Western throne until his death in 480. Up to that point, he continued to be recognized as Western emperor, at least de jure, by both Zeno and Odoacer – who minted coins both in Zeno’s and Nepos’ names!

Moreover, Odoacer himself did not last very long, and ended up being replaced with a new Western Roman Emperor in all but name. In 489, following an Eastern Roman tradition that went back to Arcadius and Alaric, Zeno, hoping to rid himself of a turbulent warlord – this time by the name of Theodoric – sent him and his Ostrogoth barbarian army from the Balkans to conquer and rule Italy on behalf of the Roman Empire. Theodoric defeated Odoacer; over the course of his long reign (493–526), he ruled with all the trappings of a Roman emperor, complete with regalia (sent back from the East) and titles (princeps, imperator).

The importance of 476 therefore has been vastly over-stated; in political and military terms, the events of the year were trivial. Even symbolically, as we have seen, the year was hardly perceived as a catastrophe by contemporaries. The Roman Empire deserves to end with a bang, not a whimper, and 476 is hardly even a whimper.

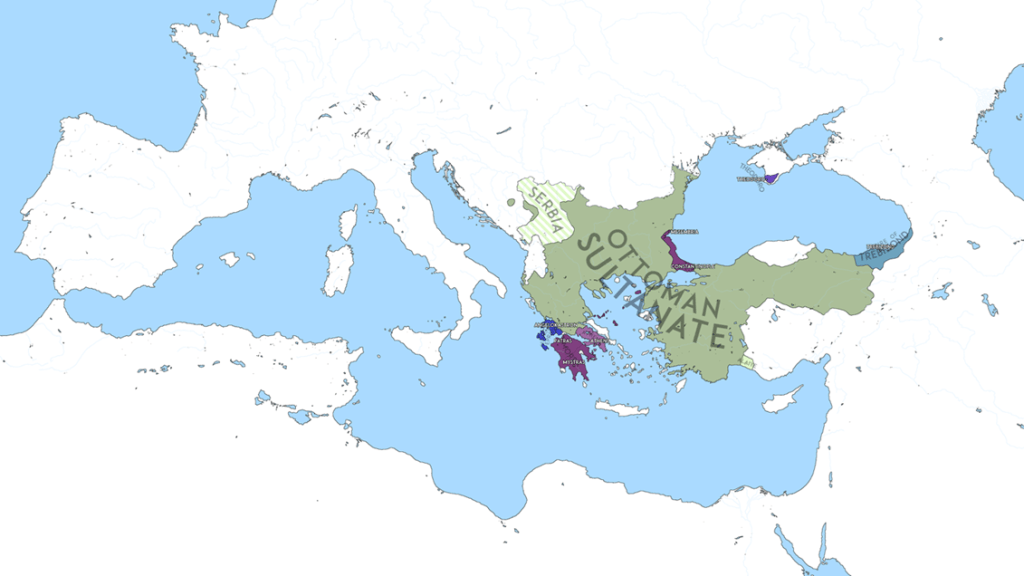

1453: The Fall of Constantinople

Say what you will about the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium), but it certainly ended with a bang. On 29 May, 1453, after an almost two-month-long siege, the Ottoman armies of Sultan Mehmet II finally stormed the city of Constantine. Outside of the small independent exclaves of Trebizond in Asia Minor and Morea in the Peloponnese, which would both fall a few years later, the city was all that remained of the empire of the Caesars. After a relentless month-long bombardment of the walls by the state-of-the-art Ottoman artillery corps, a breach was opened up in the legendary, and supposedly impregnable, Theodosian walls of the city, which had successfully defended the city against all land armies for over a thousand years.[13] As wave after wave of Ottoman shock troops fell upon the city, the defenders, outnumbered as much as ten to one, were completely overwhelmed. When the last Roman emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, realized the city would fall, he charged into the midst of the fray. His body was never found.

The New Rome was systematically looted for three days. Slaughter of civilians was followed by the rounding up of the survivors for enslavement. Soon afterwards, Mehmet set about rebuilding the city, this time as his capital. A new palace, Topkapi, would be built on the site of the old acropolis of the city. Hagia Sophia, which for almost a millennium was the largest Christian cathedral in the world, was converted into a mosque. At the same time, Mehmet went to great lengths to claim the Roman imperial legacy for himself: one of his titles, kept in the Ottoman dynasty for centuries, was kayser-i Rûm, literally “Roman Caesar”.

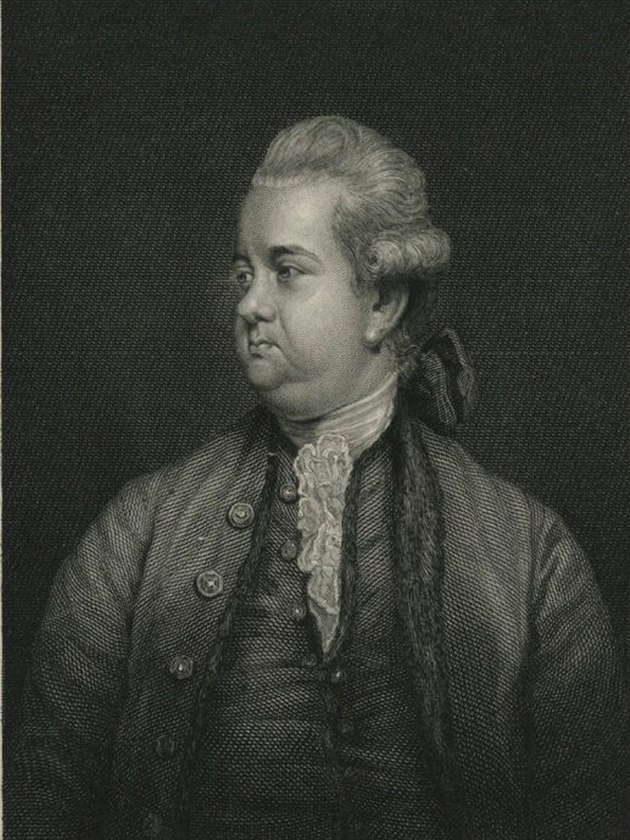

1453 has a lot to offer as a prospective year of death for the Roman empire. First, the year has some serious heavyweight backers, including Edward Gibbon himself, the founding father of all Roman Fall studies. His magisterial History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in six volumes from 1776 to 1789, remains unsurpassed. Crucially for us, Gibbon’s study, for all his obvious dislike of the Byzantines, ends in 1453.

Moreover, there is little doubt that 1453 really marked the end of a state that never actually ceased being truly ‘Roman’. The inhabitants of the Constantinople, until the very end, identified themselves as “Romans”(Ῥωμαῖοι, Rhōmaioi) and even called their (Greek!) language “Romaic” (Ῥωμαϊκή, Rhōmaïkē). For most of its subjects, the empire was the original Romania.[14]

Yet for all the symbolic resonance of the fall of the New Rome, 1453 was hardly a catastrophe for Latin Christendom in its consequences, at least to judge by the muted international reaction. Here’s Runciman, the greatest narrator of the fall of the city:

“Even in the wide political field, the fall of Constantinople altered very little… Christendom was, it is true, profoundly shocked by the fall of Constantinople… Yet the tragedy in no way changed their policy, or lack of policy, towards the Eastern Question. Only the Papacy was genuinely upset and genuinely planned counter-action; and it was soon to have more urgent problems nearer home.” (Preface, xi-xii)

Beyond the fact that the final destruction of the Eastern Roman Empire was completely inevitable, 1453 as a potential terminal year of Rome also suffers from a ‘Ship of Theseus’ paradox: regardless of how the people of Constantinople identified themselves, can we really say that the notionally Roman rump state of 1453 was the same empire as the Empire of Theodosius, or Justinian?

Indeed, the idea that 1453 marked the end of the Roman Empire would come as a surprise to many in 1453: as we have seen, the Ottoman sultans saw themselves as Roman Caesars. There was also a “Holy” Roman Emperor reigning in Vienna, Kaiser (Caesar) Frederick III, who had been crowned in Rome by the pope himself in 1452 (as had the first figure in this dynasty, Charlemagne, crowned by Pope Leo III in 800), and who naturally saw himself as the legitimate Roman emperor. Moreover, within a decade of the fall of Constantinople, the mantle of Rome was even claimed in the far North, by Ivan III of Russia, now at the head of the largest remaining Orthodox Christian polity in Europe. The Tsar (Caesar), as he now styled himself, had even married in absentia Sophia Palaiologina[15] in 1472 in Rome, to secure further legitimacy for his claim to the Roman imperial legacy. Moscow henceforth saw itself as the Third Rome, and the reconquest of the Second Rome would be the ultimate goal of Russian foreign policy for the next three and a half centuries.

From this perspective, 1453 might well represent the death of a Roman Empire, even if a shadow of its former self. Although it was certainly a glorious last stand for the imperial capital, there had been no empire to speak of for centuries. But if the well-known years of 410, 476, or even 1453 do not fit the bill, when did the Roman Empire truly end?

468: The Battle of Cap Bon

In 31 BC, the Roman Empire was born from the great naval victory of its first emperor, Augustus (Octavian), at Actium. It is perhaps fitting, then, that the same empire, whose signal achievement was the unified control of the entire Mediterranean, should have died as a result of a catastrophic naval defeat, almost 500 years later, off the coast of its most formidable rival, Carthage. Compared with the now-canonical years of 410, 476 and 1453, 468, and its climactic engagement, the battle of Cap Bon, is hardly known outside a narrow circle of Late Antiquity specialists. Yet, the events of 468 deserve to be far more widely known, given that it was the last point at which the tide could have been turned.

In 468, the Western Roman Empire’s situation was critical, but still just about salvageable. As late as 461, the Western emperor Majorian, after years of vigorous campaigning in Gaul and Spain, had largely managed to stabilise the empire, reconquering most of its provinces and successfully reining in various barbarian groups, reducing them to foederati status. The one province that eluded him was Northern Africa, which had long been the richest in the West, thanks in part to its greatest city and crown jewel, Carthage. The province was conquered by an army of Vandals (another Germanic barbarian tribe), led by king Geiseric, in 442.

In addition to depriving Rome of a crucial tax base, Geiseric used Africa not only to take over important islands such as Sicily and Sardinia, but also as a base to launch naval raids and invasions of Italy proper, further impoverishing, devastating and destabilising the Western Empire. In 455, his army even sacked Rome, and with such brutality and thoroughness that the sack of 410 seemed mild by comparison. Thus, by the 460s it had become clear that regaining control of Africa and defeating the Vandals was the key both to securing the survival of the West, and to re-asserting unified Roman control of the Mediterranean.

Majorian was assassinated in 461, in a plot organised by his devious head general, the Romanised barbarian Ricimer. He now sought to wield power himself, first through a puppet emperor (Libius Severus), and then directly, from 465 onwards, as Ricimer waited for a new Emperor to be appointed by Constantinople. In 467, the Eastern Emperor Leo I duly obliged, and appointed the Greek aristocrat Anthemius to the Western throne, ending years of instability. With East and West now pooling their resources together (for once!), the reconquest of Africa, and the Mediterranean, could begin.

Thus, by 468, a huge combined invasion force and fleet was assembled, numbering some 50,000 men and over 100 ships. The cost was correspondingly massive – some 120,000 pounds of gold (46 tons!) – the vast majority of which was shouldered by the Eastern Empire.[16] The plan was a three-pronged attack: a land force marching towards Carthage through Libya; a Western Roman fleet that would retake Sardinia and then head towards Carthage; and the main Eastern fleet, which would head straight to Carthage via Sicily. This main Roman armada was entrusted to Basiliscus, the emperor Leo’s ambitious brother-in-law.

The Romans’ strategy was never to fight a naval battle. The plan was simply for the ships to transport the invading force close to Carthage, and then disembark the troops for a land assault. At first, everything went according to plan: Libya was overrun, Sardinia was reconquered, and the main Roman fleet successfully anchored off Cap Bon, just 40 miles from Carthage. Then Basiliscus made a fatal error: instead of seizing the moment and marching on Carthage, which he almost certainly would have taken, he hesitated and, for obscure reasons,[17] ended up accepting a five-day armistice from the Vandal king Geiseric. As days passed, the winds shifted and now favored the Vandals, who then used the opportunity to send a fleet of fireboats (ships deliberately set on fire in order to set the enemy’s fleet alight) into the midst of the Roman armada.[18]

The effect was devastating. The Roman fleet was thrown into chaos, as fire engulfed ship after ship. At this point, Geiseric sprung his trap, and sent his own warships into the fray, to finish off the panicked Romans. The result was a crushing defeat: well over ten thousand dead, and the rest of the expedition scattered. Basiliscus returned ignominiously to Constantinople, where he was saved from death only by the intercession of his sister, the empress Verina.

The Northern African expedition was a catastrophe on all fronts: it crippled the financial and military might of both the East and the West. For the former, this was only a temporary disaster; for the other, it was fatal: without Africa, and without control of the sea, there was simply no way the Western “empire” could remain afloat. Politically, the defeat left Anthemius and the Western Empire without its last lifeline: the support of Constantinople, which was now bankrupt, and not to recover for another generation. Symbolically, the ship of state had finally sunk in Carthaginian waters, and the fate of the Western Empire was sealed. The Eastern Roman Empire lived on for a millennium, and would go on to have several eras of brilliance. Yet after 468, never again would the Romans be able to claim full control of Mare Nostrum. Jupiter’s providential imperium finally reached its finis.

Anatoly Grablevsky read Classics at Queens’ College, Cambridge. He is a student of archaeology, modern hubris, as well as various Hyperborean oddities, ancient and modern.

Further Reading:

Any student of the Fall of Rome would do well to begin with Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, both to get a general lay of the land and to savor his inimitable style, the closest English prose ever gets to the literary wonders of Tacitus.

The single best modern book on the travails of the Roman Empire in the late 4th and 5th centuries remains Peter Heather’s wonderfully readable The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians (Oxford UP, 2006). I have largely followed Peter’s lead on the battle of Cap Bon.

The Cambridge Ancient History Volume XIII: The Late Empire, AD 337-425 (Cambridge UP, 1998) and Volume XIV: Late Antiquity: Empire and Successors, AD 425–600 (Cambridge UP, 2001), is also a good guide to the events leading up to 410 and 476.

For 1453, Steven Runciman’s classic account The Fall of Constantinople, 1453 (Cambridge UP, 1965) remains as vividly readable as it is informative.

In terms of primary sources, Book 5 of Zosimus’ New History covers a lot of the period from 395 to 410; also indispensable is Book 3 of Procopius’ Wars, chapters 1-7.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Vade retro, socialis oeconomia! |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Haeret vox et singultus intercipiunt verba dictantis. capitur urbs, quae totum cepit orbem; Letter 127, To Principia, trans. P. Schaff. |

| ⇧3 | plurima mortis imago is imported from 2.369, four lines later. The original lines 2.361–5 read: quis cladem illius noctis, quis funera fando | explicet aut possit lacrimis aequare labores? | urbs antiqua ruit multos dominata per annos; | plurima perque vias sternuntur inertia passim | corpora perque domos et religiosa deorum | limina. |

| ⇧4 | Trans. J. Ferrante. |

| ⇧5 | If Lactantius’ Divine Institutes are anything to go by, there seems to have been a quite widespread belief among Christians that the fall of the city of Rome would herald the Apocalypse (7.25). |

| ⇧6 | Admittedly this was done at the expense of defending other provinces, most notably Gaul, which was invaded in 406 by various Germanic tribes, including the Vandals. The barbarians were able to penetrate as far as Spain, which would have grievous consequences for the empire later on. |

| ⇧7 | For example, defeating the barbarian army of Radagaisus in 406. |

| ⇧8 | So peripheral was the city to their concerns that most emperors from the mid-4th century onwards did not even bother visiting it. |

| ⇧9 | One representative example is E.H. Gombrich’s classic A Little History of the World (1935). Writing on the significance of 476, he observes: “This marked the end of the Roman Empire of the West and its Latin culture, together with the long period that goes all the way back to prehistoric times, which we call ‘antiquity.” |

| ⇧10 | A correct assessment: by 476 the Western Empire barely controlled even Italy itself. |

| ⇧11 | To this effect, see fragment 2 of the contemporary historian Malchus. |

| ⇧12 | Whether in Cassiodorus’ Variae or in Ennodius’ Vita Epiphanii. |

| ⇧13 | The only time Constantinople had fallen prior to 1453 was in 1204, but that was largely an amphibious operation. |

| ⇧14 | The adjective “Byzantine” to describe the Eastern Empire as a whole was never used by the Eastern Romans, and dates to the Renaissance period. It did not become the standard designation for the Eastern Roman Empire until the 19th century. In Eastern Roman sources, “Byzantium” is only used to designate Constantinople itself. For more to this effect, see the work of Anthony Kaldellis, such as Romanland (2019). |

| ⇧15 | One of the last scions of the Eastern Roman imperial dynasty. |

| ⇧16 | For reference, that is about ten times the cost of Justinian’s Hagia Sophia, which when built was the largest church in Christendom. |

| ⇧17 | According to Procopius (Wars 3.6), treachery was afoot, as Basiliscus was bribed by Geiseric to accept the armistice. However, given how often treason is brought up as an excuse for failure in Roman history (Heather 2006), one should probably not attribute to treachery what is much more easily explained by incompetence, or overpowering ambition. |

| ⇧18 | As Heather notes, this is exactly the same tactic that the English used against the Spanish Armada in 1588. |