Gary F. Fisher

This coming Thursday, on 4 July 2024, the UK is scheduled to go to the polls in a General Election. At the time of writing, a victory for Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour party is the expected result, with polls indicating a Labour majority ranging in scale from comfortable to almost absolute. One of the more prominent policies proposed by the Labour party is an additional 20% tax on tuition fees at independent schools across the UK. With a year of tuition at an independent senior school within the UK costing an average of a little over £20,000 per child between the ages of 11–18, this could mean an additional annual cost in the region of £4,000 to parents and carers sending young people to fee-paying schools.

This additional cost may do little to deter those in particularly high-income brackets from sending their children to independent senior schools – for example, the incumbent Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s parents, whose jobs as a GP and a pharmacist enabled them to send him to Winchester College, which presently charges approximately £50,000 for a single year of tuition, and numbers amongst the UK’s most expensive independent schools. It could, however, suffice to preclude members of the professional and upper-middle classes from sending their children to less notable, yet still fee-paying institutions – such as Sir Keir Starmer’s parents who were able to send their son to the fee-paying Reigate Grammar School, which currently charges approximately £21,000 a year. The Independent Schools Council (ISC), a body that represents and advocates for the interests of independent schools, has suggested that this tax could reduce student numbers by anywhere between 17.1% and 25.4%. A report by the House of Lords has estimated that this may place up to 75% of independent schools at risk of closure.

This could have profound implications for the position of Classical learning within the UK’s educational landscape. The public perception of a Classical education as being the preserve of these elite institutions is not undeserved. Yet it is certainly the case that great efforts are being made across the country to provide opportunities for access to a Classical curriculum for everyone regardless of financial status. Many universities with Classics departments operate schemes and events to raise the profile of the Classics in nearby schools and colleges, while charities and networks including Classics for All and Classics in Communities exist to disseminate expertise and enthusiasm for the Classics outside of those who attend fee-paying institutions. It is a testament to the impact of these efforts that during the 2022–23 academic year, there were a little under 10,000 students from state-funded schools (both selective and non-selective) who were entered for A-Level Classical Civilisation.

Despite this progress, students from fee-paying institutions continue to be over-represented amongst those studying Classics at school. Although only approximately 7% of secondary school-aged children across the UK attend a fee-paying school to GCSE, and around 12% at A-Level (with many more pursuing the International Baccalaureate instead), students at these institutions account for 33% of candidates entered for A-Level Classical Civilisation.

The tax on independent education being proposed by the UK’s increasingly certain Labour government, and the contraction in the independent schools sector it could plausibly occasion, will very probably endanger currently-available opportunities for young people to access formal schooling in the Classics across the UK. It is thus important to contemplate what the landscape of Classical learning across the UK may look like if one discounts these institutions. We should also consider the impact that any contraction in the independent school sector may have on young people’s opportunities to access formal schooling in the Classics.

Despite the incumbent Conservative government’s ‘levelling-up’ agenda, the UK remains starkly divided along regional lines on a variety of matters, but especially education. There are numerous counties across the UK in which the only schools formally offering the Classics on their curriculum are independent. Within England and Wales, local education authorities are responsible for overseeing state-maintained educational provision within their area of jurisdiction. As David Tristram has shown in his contribution to the 2003 volume The Teaching of the Classics, these bodies are often sceptical of the relevance of the Classics to contemporary students and have proved themselves reluctant to divert scarce resources to their teaching.

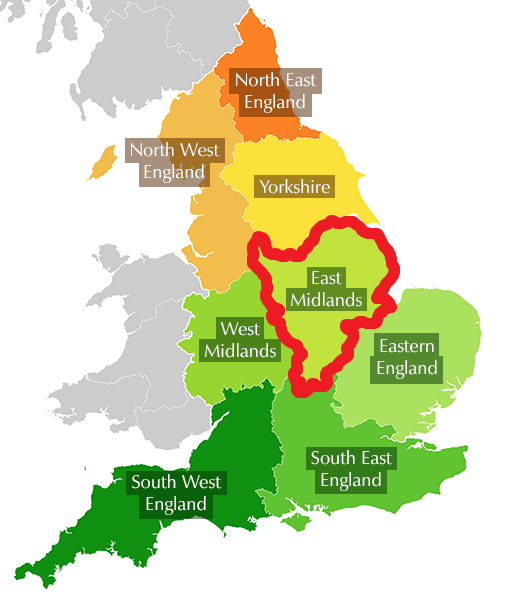

A 2019 study published in the Bulletin of the Council of University Classics Departments found that, of the 113 local authorities across England, 73 do not include a single state-maintained centre offering young people the opportunity to study Latin at A-Level. Of the 68 state-funded centres in England offering A-Level Latin to their students, 38 were located in London or the South-East, while only one was located in the North-East, and two were located in the East Midlands, all three of which were academically selective schools.

This has implications beyond geography: according to the online real-estate portal Rightmove, the average price of a property in the East Midlands is £264,952, compared with £720,494 in London. The London Oratory School, for example, is a state-funded senior school that offers its students (including the children of former Prime Minister Tony Blair) the opportunity to study Classical Civilization, Latin, and Greek. It also sits within a postcode where the average price of a terraced house is currently £1,786,664. Access to these institutions is constrained not just directly by proximity, but indirectly by financial means to ensure that proximity. The position of Classics outside of these national centres of extreme wealth is already precarious. Any contraction in this independent sector, even if only by a fraction of that suggested by the ISC, would put this already-precarious position at further risk.

The repercussions of this policy will surely be felt beyond the immediate secondary-education sector, and could impact the position of Classical learning throughout the landscape of UK education. Let us consider the example of the University of Nottingham, which educates upwards of 100 undergraduate and postgraduate students per year on its Classics, Classical civilization, and ancient history programmes. According to records maintained by the Association for Latin Teaching, there are currently only three senior schools within the entire county of Nottinghamshire that offer Classical Civilization or Latin at A-Level, all of which are fee-paying: Worksop College, Nottingham Girls’ High School, and Nottingham High School (the alma mater of former Shadow Secretary of State for Education Ed Balls). Excluding these institutions, there are no opportunities for young people in this county to engage in formal study of these qualifications within a school or sixth-form setting.

To compound this, if one looks further afield to non-fee-paying institutions in Nottinghamshire’s neighbouring counties of Derbyshire, South Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, and Leicestershire, there are currently only three selective grammar schools (two of which are sex segregated) and one city-centre sixth-form college offering young people the opportunity to study these subjects at A-Level.

If one imagines an educational landscape of which independent schools form no part, the University of Nottingham would sit within a region of five counties and over 15,000km2 with a population of approximately 4.5 million people in which only a most extreme minority of 16–18 year-olds would have the opportunity to study Classical subjects through their school or college. Given that over half of Britain’s undergraduates attend a university that is fewer than 55 miles away from home, the sustainability of a higher-education institution offering a subject while sitting in a desert of its preceding level of instruction is highly questionable, to say the least.

There is a risk of pessimism here, which must be appropriately moderated. First, it is unlikely that independent schools as a phenomenon would wholesale disappear upon the introduction of a 20% tax. While the more peripheral ‘lesser’ schools may experience sufficient challenges as to be put at risk of closure, the more prominent independent schools are probably at lesser risk. It is also worth acknowledging that the ISC, who have been vocal in their opposition to and predictions of negative outcomes from this tax, are, by design, an organisation that exists to advocate for and promote independent education, and so their predictions must be understood in this context.

Second, even the most extreme case scenario, in which numerous independent schools face closure and their prospective students reallocated to state-funded schools, does not necessarily mean the total erasure of Classical pedagogy/expertise that they contained. Classics professionals at a hypothetically shuttering independent school may very well relocate to a proximate state-funded school and implement a Classical curriculum. It’s difficult to estimate how feasible this is; data that we might use as a proxy concerning factors such as teacher retention and rates of re-entering the profession after leaving don’t paint a particularly encouraging picture. That said, one potential, highly optimistic, outcome of a hypothetical contraction in the independent school sector might be a translation of Classical learning out of regional independent schools and into nearby state-funded senior schools and sixth form centres.

As Mary Beard wrote in the introduction to her 2013 Confronting the Classics, ‘there is no generation since at least the second century AD that has imagined that it was fostering the Classical tradition better than its predecessors’. It is important to put this pessimism within the context the excellent ongoing work done by third-sector organisations such as the Classical Association and Classics for All, which advocate for Classical study to a broader population (not to mention Antigone, the open-access platform on which this very article is being hosted). Finally, one must note the growing number of autodidacts independently using open and free-to-use resources to study the Classics, such as the upwards of 2 million people globally who are learning Latin on Duolingo.

However, any change in the landscape of fee-paying education will surely reverberate through the landscape of Classical learning across the United Kingdom. Formal study of the Classics already has financial barriers. As the nation faces a plausible contraction within the independent school sector, there is a risk of these inequalities of access being further entrenched and compounded by geographical barriers. Even within those independent schools that are able to remain open in the face of this additional tax, it is plausible that the heavier tuition fees it generates could place their Classics provision under pressure.

Leaders and managers within these institutions may feasibly be prompted further in the direction of educational utilitarianism, emphasising subjects with greater tangible economic value to their students at the expense of the Classics and other arts and humanities subjects whose value is less materially quantifiable. Classicists and Classics educators will need to acknowledge and face these challenges head on in order to mitigate these risks and maximise any opportunities for growth amidst this changing landscape.

Gary F. Fisher gained his doctorate in Classics from the University of Nottingham in 2020 and is currently the University of Derby’s Learning Design and Online Practice Manager. Prior to this, he has worked in contexts including further education colleges, rehabilitative institutions, and heritage organisations. He has published original research and reviews on topics including the politicisation of Classical learning in revolutionary America, strategies for teaching the classics in prison settings, and contemporary uses of educational technology in universities.

Further Reading

The 2003 volume The Teaching of Classics edited by James Morwood offers an excellent critical survey of the status of Classics within UK education, with its first section sketching the evolution of Classics within the national curriculum to the end of the 20th century.

To read further about inequalities of access to the Classics in contemporary England, Steven Hunt and Arlene Holmes-Henderson’s 2021 article ‘A level Classics poverty Classical subjects in schools in England: access, attainment and progression’ (available here) offers a detailed breakdown of how access to Cassical subjects varies according to region and context. This article offers a detailed picture of the landscape of Classical learning across the nation and delves further into the details of how this disparity has emerged.

For raw data detailing entrants to and performance during different A-Level subjects, the UK government maintains a current record of ‘A level and other 16 to 18 results’ that details the number of students taking different A-Level programmes within the ‘Classical studies’ subject area.