Jaspreet Singh Boparai

Since September 2023, six of the nine Triumphs of Julius Caesar by Andrea Mantegna (1431/2–1506) have been on display at the National Gallery in London. These paintings, each nine feet high and nine feet long, together form one of the highlights of the Royal Collection of the United Kingdom. Not only that, they are among the very greatest manifestations of Classicism in Renaissance art. Most of the time Mantegna’s Triumphs can be seen together at Hampton Court Palace, but these six will remain in London until the end of 2025 whilst their usual home undergoes restoration work.

These monumental images have been famous ever since they first went on view in the 1490s; Giorgio Vasari (1511–74), the pioneering biographer of Italian Renaissance artists, thought that the Triumphs were Mantegna’s greatest accomplishment as a painter. Most experts continue to agree with Vasari. Throughout his life, Mantegna was obsessed with Roman grandeur; he studied ruins, and collected antiquities – gems, coins, medals, statues, anything he could afford – until it often became impossible to tell whether he was copying ancient art or inventing scenes out of his own imagination. Nobody could paint historical scenes the way he could.

Mantegna was prodigiously learned: his thirst for knowledge is inextricable from his creative drive. The Hungarian humanist Janus Pannonius (1432–74), who got to know him whilst studying canon law in Padua during the 1450s, called him “the Livy of Painting”. This sounds like a backhanded compliment until you see how it is, in fact, the highest possible praise.

Where the Classical tradition was concerned, Mantegna’s contemporaries tended to be tentative and reverent, in part because – unlike him – most knew little (if any) Latin, and relied largely on better-educated advisers for information about history and literature. Mantegna, by contrast, had the confidence to treat ancient art as a starting point for his imagination, rather than something to be reverently copied and imitated. He was one of the first artists to treat Roman sculptors as his peers rather than his superiors. In some ways he had more in common with literary and scholarly humanists than with the other great artists of the 15th century.

What Petrarch (1304–74) was to Classical literature, Mantegna became for painting. Indeed, he was possibly more than that. Petrarch is the father of the Italian Renaissance, of course: nobody did more to help recover the literary and archaeological heritage of ancient Rome. Also, he was a fine Latinist, and a formidable scholar, as well as a great literary artist, in Latin prose no less than vernacular poetry (although his sonnets are obviously his most enduring work). Yet he could never quite equal his ancient masters, at least where hexameter verse was concerned, because he approached their work from a cringing, subservient posture, and not as an equal seeking friendly competition. As a result, his Latin-language hexameters are always ‘verse’ rather than ‘poetry’.

Petrarch’s Africa is an attempt to revive the Latin epic essentially through taking Livy’s accounts of the Second Punic War and transforming them into hexameters. The result is worth studying for any number of reasons, but artistically it is a failure. Petrarch was teaching himself about his subject whilst trying to imagine it, and seems to have been overwhelmed by his research. Because he failed to digest his sources, you can clearly see (for example) how closely and nervously he hews to his material, and is afraid to say more than Livy did at the end of Ab Vrbe Condita 30 about the triumph of Scipio Africanus, except to try to elaborate it with recognisable references to a handful of other suitably grand Roman poets. Mantegna had no such fear.

Influence or Inspiration?

Mantegna is the first Renaissance painter to treat ancient art as an inspiration rather than an influence. The distinction is a hazy one, perhaps. Even so, it surely seems clear that ‘influence’ is easier to trace than ‘inspiration’. If something ‘influences’ me, it flows in and over my work recognisably, whether or not I am conscious of the process: when influenced, I copy or imitate more or less passively, even if I am aware of what is going on, and continue to exercise and judgment. You can discern the results of ‘influence’, and draw direct lines between what I have created and what my influences were.

Inspiration is different – a more mysterious, mystical process. When you ‘inspire’ an artist, you breathe life into him, and the work he creates, in ways that frustrate the literal-minded because they can only be described in metaphors of the sort that cannot be cleanly reduced to some linear, step-by-step process. It is easy to discern Aristotle’s ‘influence’ on a given systematic philosopher of the Hellenistic period, and difficult to talk about how Plato ‘inspired’ such-and-such a Romantic-era composer, at least in a way that makes sense.

As a fledgling artist, Mantegna was influenced by Donatello (1386–1466), the formidably skilful Florentine sculptor who lived and worked in Padua from 1443 to 1453. Art historians can prove how Mantegna studied Donatello’s work, not least his brilliantly imagined relief plaques, because it shows in his paintings and engravings. There is evidence of copying. Without much in the way of documentary evidence, or (for example) accounts of encounters between the two men, we can demonstrate how Mantegna learned at least as much about the composition of a narrative scene from the example of Donatello’s reliefs as he did from systematically drawing Roman sarcophagi (or other artists’ drawings of them).

Donatello’s David from the 1440s has long been celebrated as the first freestanding bronze nude to have been produced since antiquity. Technically this is an impressive achievement; artistically it is nowhere near Donatello’s most original work. You can identify elements that remind you of, for example, a statue of Antinous that the artist is likely to have seen; you can guess the artist’s sources with reasonable certainty. To admit this isn’t to take away from Donatello’s achievement: indeed, he meant you to think of this statue as derivative of ancient models. Its main originality involves its use of Graeco-Roman visual language to depict a character from the Bible; in this way, Donatello thinks of himself as surpassing his pagan influences, because he is asserting a superior, Christian truth.

Compare Donatello’s David to the David (1501–4) of Michelangelo (1475–1564), a colossal marble nude on a scale that no sculptor had been able even to dream of attempting since the 3rd century AD. Donatello’s David is a masterpiece, yet it inspires admiring contemplation rather than awe. You can study it learnedly as the sum of its influences, and appreciate the artist’s intelligence as well as his skill, whereas Michelangelo’s David is a work of God-given genius.

Michelangelo’s work is ‘Classical’ not because it adopts or adapts discrete elements from ancient Roman art; rather he has so comprehensively absorbed and digested every possible Classical antecedent that he has revived their language, and even refined it.

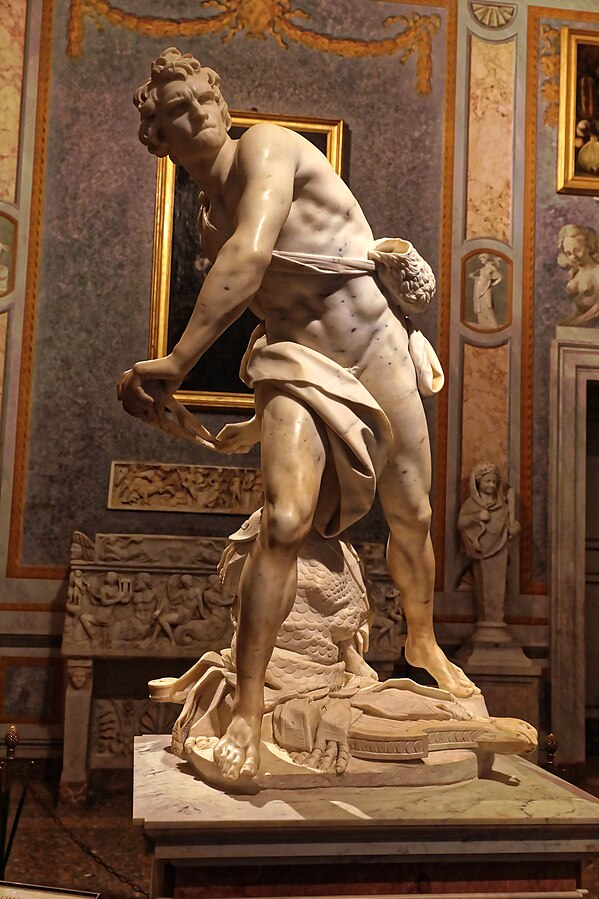

Later sculptors treated David as a miracle never to be equalled; Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) avoided competing with it directly in interesting ways: instead of trying to produce a David who looked like a Greek god, he created a David that ‘quotes’ ancient sculptures, and resembles a local Roman youth rather than a perfect, universal, idealised ‘Classical’ figure. You can identify various influences on Bernini whilst recognising Michelangelo as his single greatest inspiration: he was always trying to create something that somehow surpassed Michelangelo.[1]

Unlike Bernini, Petrarch or Donatello, Mantegna did not work in the same medium as his potential influences or inspirations: to translate written words and/or sculptures and Roman coins into full-colour paintings inevitably demands a process of imaginative transformation. Mantegna was forced to create the tradition in which he worked.

Mantegna’s Educated Imagination

We know relatively little of Mantegna’s early life: he was born in 1431/2 near Padua. His father was a master carpenter; from 1442 to 1447/8 he was apprenticed to Francesco Squarcione (c.1395–1468/74), a former tailor who was not a gifted artist himself, but had a remarkable eye for talent; Mantegna was not his only famous pupil. Squarcione was allegedly unscrupulous and exploitative; however, he at least introduced Mantegna to Roman art, and may have taught him the rudiments of Latin.

Some scholars assume that Mantegna had barely enough Latin to get through Julius Caesar’s Commentaries. But he had more than enough to be able to learn from the ancient historians and various neo-Latin antiquarian texts that can be a challenge even for Classicists. Unlike us, he could not rely on translations as a shortcut to knowledge. We often forget that Mantegna was essentially an autodidact: he devoured books, treating them as ‘data mines’ for facts and hard evidence that could feed his imagination; he had no time for literature as an end in itself.

Mantegna’s best friend among scholars was the eccentric antiquarian and calligrapher Felice Feliciano (1433–79), who appears to have advised him on literary matters. According to legend, they went together on an expedition around Lake Garda in September 1464 to look for ancient monuments and inscriptions. The surviving account of this trip seems embellished, and probably amounts to a romanticised vision of the sort of trip that Feliciano wanted to make with his learned friends, rather than a depiction of reality.

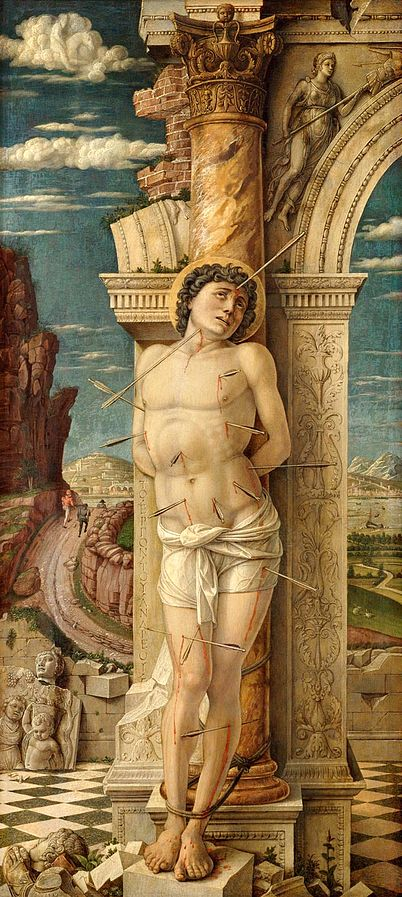

Whatever the truth of his antiquities-hunting adventures with Feliciano, it seems undeniable that Mantegna was a shrewd, knowledgeable collector. Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449–92) is recorded as having visited his house on 23 February 1483 and been genuinely impressed at the range and quality of the antiquities on display. You can guess this from looking at one of Mantegna’s pictures, and admiring the intelligent use he makes of Classical imagery, and ruins especially, to explore his subject matter. His depictions of Saint Sebastian are particularly interesting in this respect.

You will note, to the left of the saint’s leg, an inscription in Classical Greek proclaiming that this is “the work of Andrea”. Mantegna almost definitely had no Greek; during the 1460s and 1470s there were no more than a few hundred competent Hellenists in Italy. The friend who wrote out this rudimentary translation for him was probably unable to write much more than this. Far more interesting than the inscription is the curious imagery of ruins and broken statues in this picture. A second Saint Sebastian from around 1480 (formerly part of an altarpiece) tells a slightly different story in similar language.

Saint Sebastian was martyred at some point in the late 280s AD, during the persecutions of Christians that came to a head under the Emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305). According to the earliest accounts of his life, he was tied to a stake or tree and shot repeatedly at by archers, then left for dead; by miracle he managed to survive, and was later cudgelled to death after haranguing the emperor for his cruelty towards Christians. Church historians regard the martyrdoms during Diocletian’s age as a sign of official desperation and weakness, just as Saint Sebastian himself allegedly did. The Great Persecution eventually fizzled out; within a generation Christianity dominated the empire. In these pictures, Mantegna hints at the exhaustion of those who claimed to worship the gods of their ancestors, but no longer had any faith in them.

Mantegna depicts the saint as being tied to a column in a Roman ruin, rather than a piece of wood. This cannot be an accident. The symbolism is in general difficult to read until you suddenly realise how clever it is: Roman paganism is dead and broken; the persecuted Christian witness, tied to a broken monument (a fallen victory arch?) in a lifeless landscape, is still alive; indeed, he is the only full, intact figure, other than the distant labourers humbly going about their business in the Louvre’s Saint Sebastian, and the pair of travellers (perhaps towards Jerusalem?) in the Vienna picture. In the earlier picture, there is a figure of Victory above the martyr’s head.

The imagery in both of these is complex and enigmatic; there is no need to give a full account of it here. At least it ought to be obvious that the ancient statues and Classical architecture in these paintings are not there merely as pretty imagery. On the other hand, we ought to be careful about over-interpreting images like this, or articulating intellectual complexities that are better silently contemplated than spelt out in words. Art criticism always involves tricky navigation between Scylla and Charybdis.

Mantegna’s 1459 version of The Agony in the Garden (in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tours, France) includes a fascinating attempt to depict Jerusalem as a specifically Roman provincial city, even if it now looks like a Renaissance construction to our eyes. How far should we try to read this aspect of the painting, except as the fruit of passionate yet unsystematic investigations of ancient architecture and archaeology?

Ideas Made Flesh

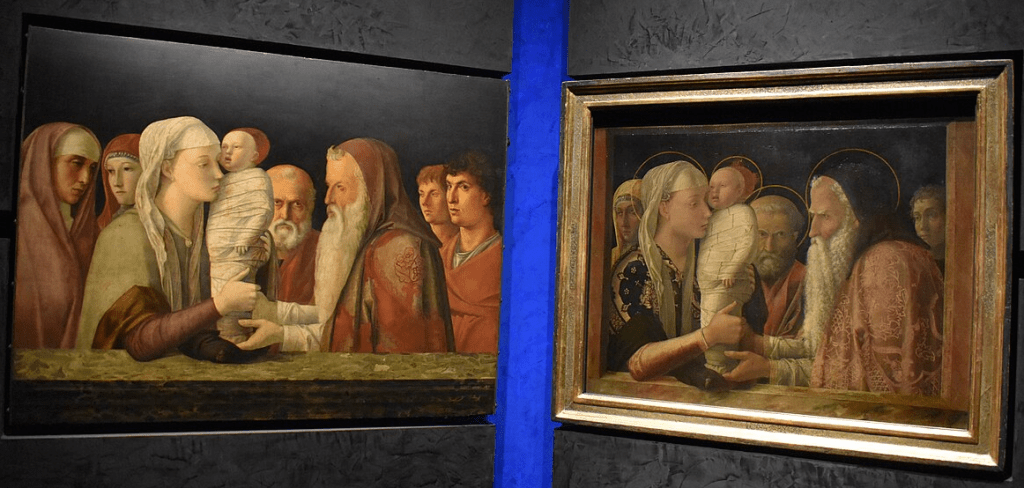

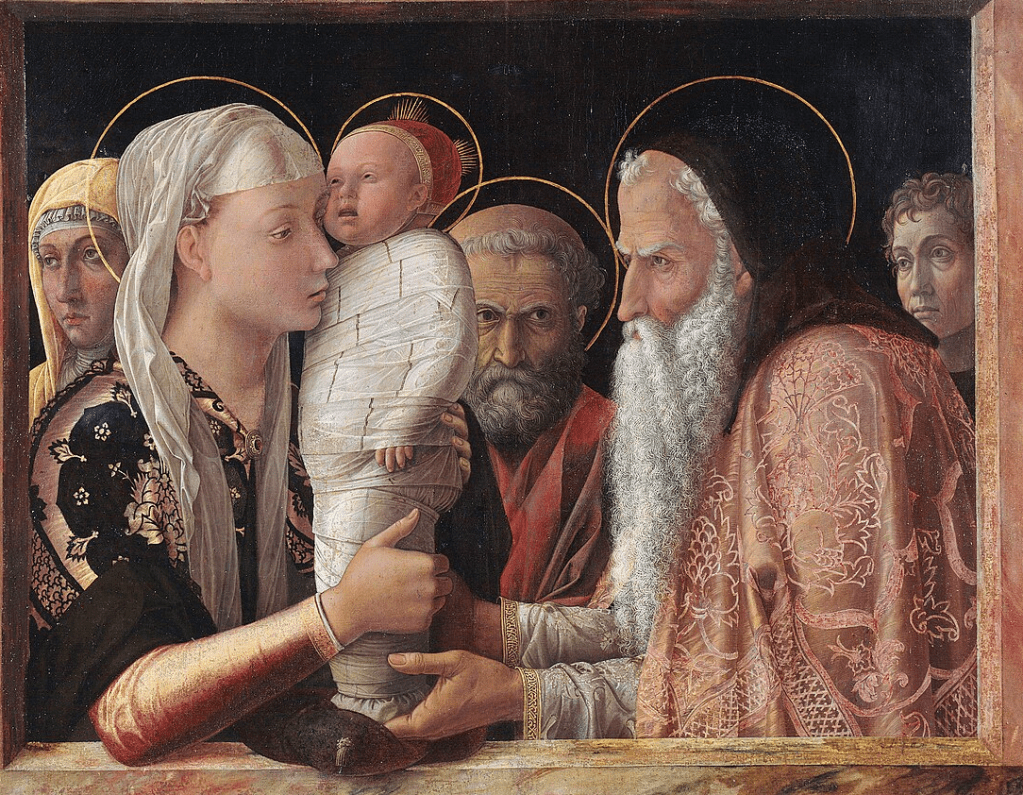

Mantegna’s greatest skill was disegno, which is usually translated as “drawing” or “design”, but might better be understood as the art of giving form to an idea. This aspect of Mantegna’s work is easier to see in his prints and drawings than his paintings, perhaps, where the eye can be overwhelmed by the sheer wealth of visual information. Also, to modern eyes, Mantegna is perhaps not much of a painter. This is in part because he often worked not in oils but in egg tempera, which dries quickly and is much less flexible as a medium than oil paint. Compare an original tempera painting by Mantegna to a copy in oils by his brother-in-law Giovanni Bellini to get some idea of the differences:

The hard, linear quality of much of Mantegna’s work makes a virtue out of technical necessity; indeed, his oil paintings demonstrate a certain caution about going too far with the medium. As a printmaker he was often much bolder. His 1475 engraving The Flagellation of Christ is a remarkable depiction of a familiar scene from the New Testament: one of the key moments in the Passion of Jesus Christ is presented as an ordinary scene in a provincial garrison. The Saint Sebastian pictures show the Roman Empire in a moment of weakness, chaos and decay; here, on the other hand, you are impressed by the calm, casual boredom of Roman soldiers who have no need to question their grip on power. This is particularly striking from a Christian point of view.

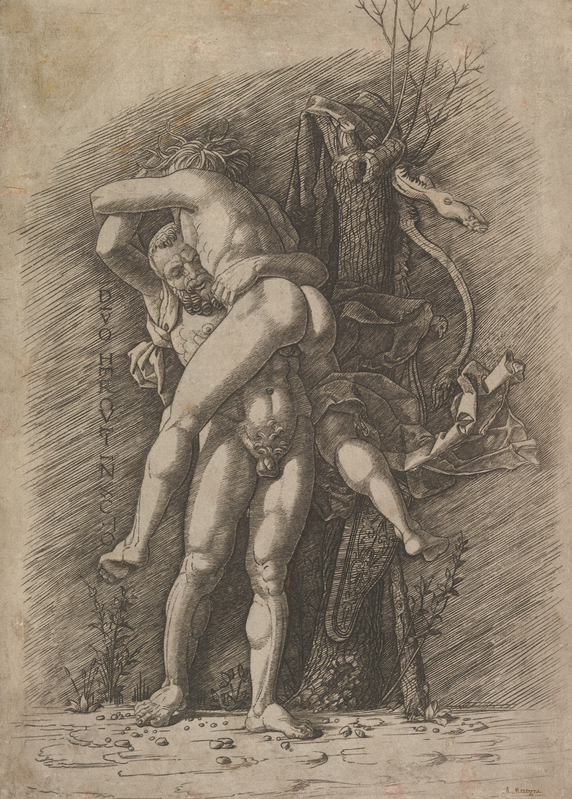

There is some controversy as to whether Mantegna engraved his prints himself, or entrusted the technical work to a professional goldsmith (as most artists did well into the 16th century). Individual copies can be of variable quality; some of the world’s greatest collections own poor impressions of Mantegna engravings that have quietly been touched up with pen and ink. Historians often identify Gian Marco Cavalli (1454–1508) as the collaborator behind works like the 1497 print of Hercules and Antaeus. The design in these, at least, is recognisably Mantegna’s.

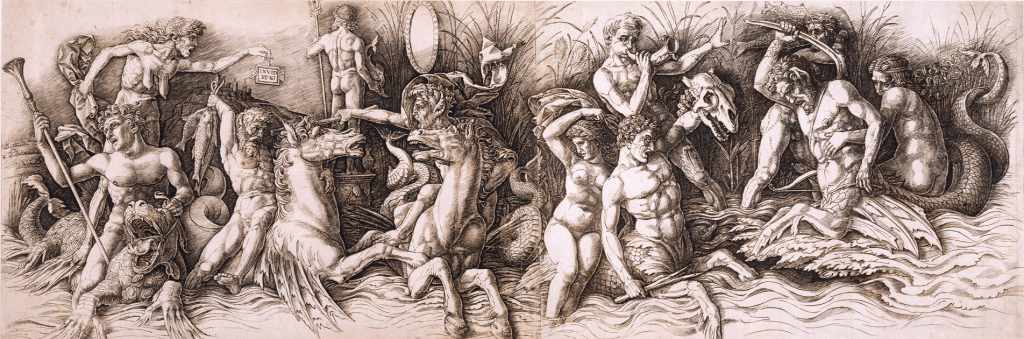

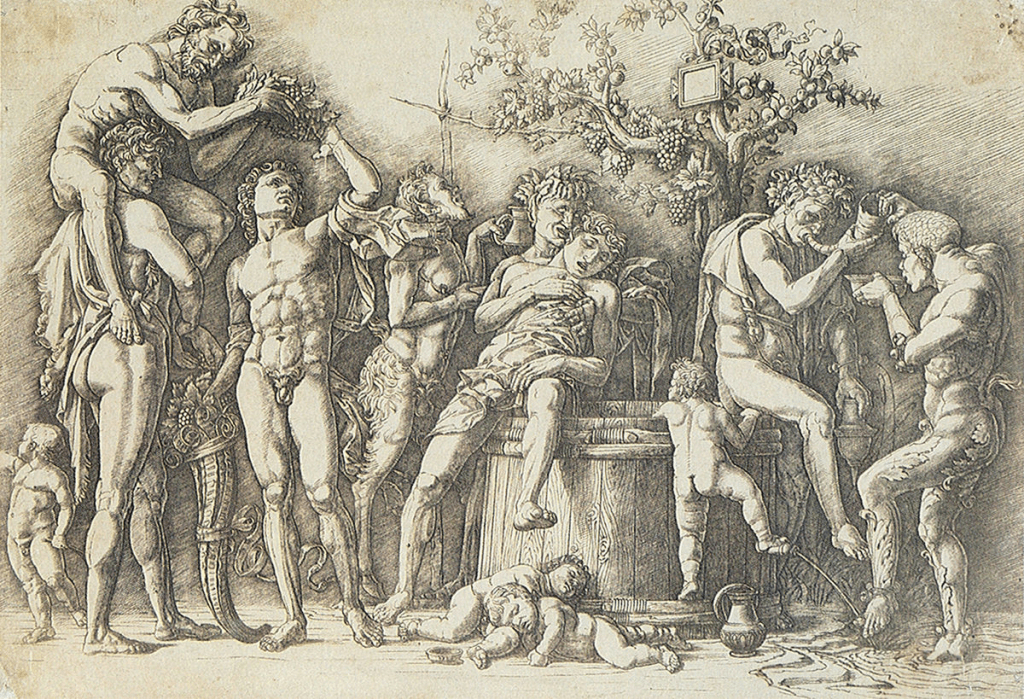

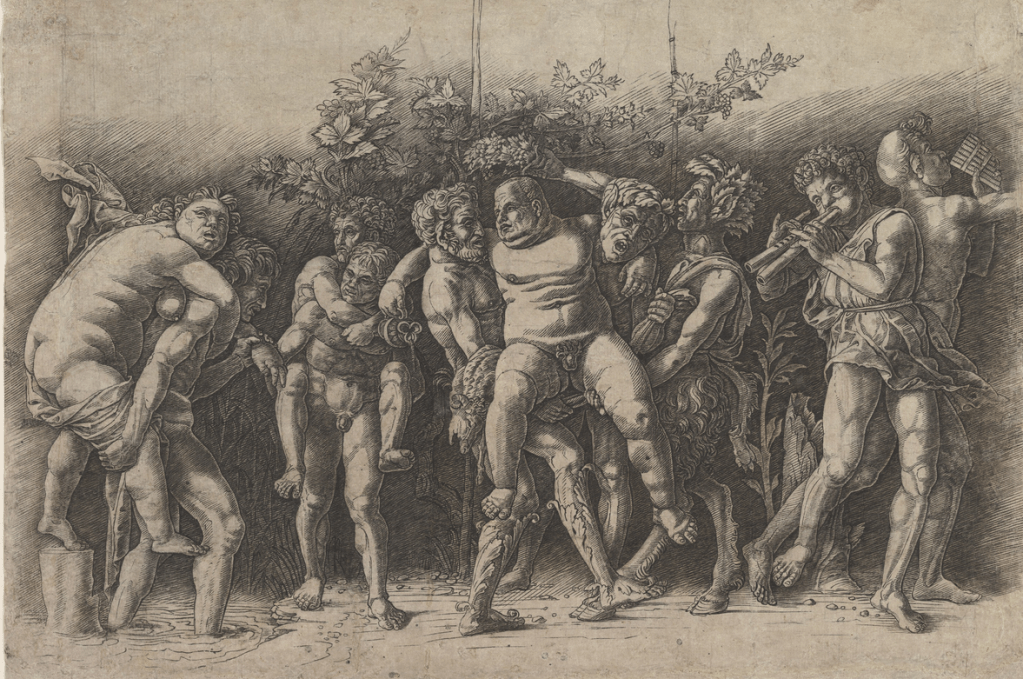

Among Mantegna’s prints, the Bacchanals, and the splendid Battle of the Sea Gods, are perhaps the best evidence we have of the fundamentally un-literary nature of Mantegna’s creative imagination. He can illustrate a text perfectly well, and reconstruct scenes from the New Testament in ways that seem to have occurred to no other artist, as we have seen above; yet the written word itself appears to have left him cold. Latin did not obviously attract him as a language; he was more interested in how it enabled him to absorb the concrete details and hard facts that really fired his imagination. His finest work communicates without the aid of verbal explanations.

Does The Battle of the Sea Gods owe anything to Mantegna’s reading? The “sea gods” here are doing what ordinary mortals do to one another on beaches, lake shores and riverbanks at the end of hot summer days, when alcohol is involved. Neptune and Invidia (“Envy”) are clearly identifiable; the rest of the figures are the artist’s own inventions. There is no need to assume a written source for this image, poetic or otherwise: Mantegna was simply letting his imagination play freely over a range of ancient decorative elements to tell a familiar story about what happens when envy and drunkenness collide.

Perhaps the Bacchanals owe something to Donatello’s spirited depictions of cherubs behaving badly, which themselves originate in Roman sarcophagi and decorative friezes; but again, these are surely the result of experience, personal observation and the effects of drinking to excess. Mantegna could have come up with scenes like this without consulting the work of moral philosophers.

The Classical imagery in these pictures might be considered a smokescreen or fig leaf – a means of lending dignity to low subject matter. Scholars often twist themselves into knots trying to explain these prints, and figure out their intellectual significance, which might come from their relationship to some prestigious written text or other. Imagine looking at the Bacchanal with Silenus and trying to assert with a straight face that this has anything to do with (say) one of Vergil’s Eclogues. It seems more reasonable to suggest that Mantegna was having fun with his work, and exploiting the contrast between the inherent prestige of Classical visual language and the sordid behaviour of pagan deities, as encountered in (for example) Ovid. He loved ancient history, but had no time for Roman myth. There may be a sincerely Christian element to his attitude.

Mantegna thought hard about what he put on paper (or canvas), and aimed to create images that embodied ideas, and could speak for themselves; he did not want his work to depend on mere words to render them intelligible. This is true even of pictures where he had no control over the content. In 1497, Isabella d’Este (1474–1539) commissioned Mantegna to paint some allegorical scenes for her private study; the subject matter was plotted out for him by Paride de Ceresara (1466–1532), a poet whose work is forgotten today even by experts.

This picture of Mount Parnassus was heavily retouched after Mantegna’s death, and is thus not the best example of his skill as a painter; but the composition and arrangement of colour at least ensure that the scene is legible, particularly if you have some idea of who Mars, Venus, Mercury, Apollo and Vulcan are, and what Pegasus is, and what the Nine Muses do on Mount Helicon. It doesn’t matter that Paride de Ceresara and/or other humanist advisers put the Muses on the wrong mountain – the intelligent viewer gets the point of what is going on here.

A subsequent picture for Isabella d’Este, Pallas Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtues, is surprisingly easy to understand even without help from a written guide. There are some interpretative difficulties here and there, but by the standards of Renaissance mythological allegories, it really is not a puzzle.

Mantegna wanted painting and printmaking to stimulate the intellect as well as the senses and emotions just as written words did: for him, visual art was no less dignified or civilised than music or poetry. You could enjoy a song without relying on critical interpretation or a learned explanation; why could the same not be true of a picture?

Mantegna’s Triumphs

We know surprisingly little about Mantegna’s greatest work, The Triumphs of Julius Caesar. The best introduction is still Andrew Martindale’s mammoth 1979 study The Triumphs of Caesar by Andrea Mantegna, with an introduction by Sir Anthony Blunt, Professor at the Warburg Institute, Director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, Honorary Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge – and Soviet spy.

Mantegna was at work on the Triumphs by 1486; they were still unfinished in 1492. In fact, they were never really finished: we have nine paintings; a tenth was planned, but Mantegna died before completing it. The original drawing of the tenth image is lost, but we do at least have prints and other copies.

No patron asked Mantegna to create these pictures – in other words, the Triumphs were a personal project, not a commission. Before the 19th century, even the most renowned artists rarely worked for themselves like this. Mantegna decided, of his own accord, to paint Julius Caesar’s legendary ‘quadruple triumph’ of 46 BC, when he celebrated his Gallic, Alexandrian, Pontic and African victories in succession during a single memorable fortnight. The Gallic triumph was the most splendid of all; this is the one that Mantegna chose to depict in his masterpiece.

There is no single source for these paintings. Suetonius describes the ‘quadruple triumph’ vaguely in his life of Julius Caesar; there is a little more detail in Plutarch’s biography (which was available in a printed Latin translation by 1470). For details of other triumphs, Mantegna could have consulted Livy, or Latin translations of Appian, and of other lives by Plutarch. Most scholars assume that he relied in part on the works of the humanist Flavio Biondo (1392–1463). The tenth book of Biondo’s famously dense scholarly study Roma Triumphans (completed in 1459) focusses on Roman triumphs. There are other possible contemporary sources, including a now-lost treatise, De Triumpho (On the Triumph), by Mantegna’s friend Giovanni Marcanuova (1415–67). But texts by themselves could never tell the artist what he really needed or wanted to know.

The sheer quantity of material that Mantegna committed to memory over the course of his life – not just coins, medallions, statues and inscriptions, but drawings of antiquities and ruins, and written descriptions of Roman art and architecture that he couldn’t see – enabled him to guess what a triumph really looked like, and reconstruction one in his imagination with what seems like startling accuracy. We emphasise his imagination here not least because he only visited Rome for the first time in 1488, after he had already started to design the Triumphs. Thanks to his studies, he already had an excellent idea of what Rome looked like in antiquity.

Were the Triumphs simply an excuse for Mantegna to show off his knowledge? His decision to focus on Julius Caesar for his most ambitious single project is difficult to interpret. At least this is not an obscure subject: even today, fledgling Latinists rarely avoid Caesar’s prose. Most of us encounter him at a point when we are still stumbling over grammar, syntax and vocabulary, unable to appreciate the author’s intelligence or artistry. To read Caesar’s Commentaries in maturity is to be confronted with hidden depths, complexities – and stumbling-blocks that are intellectual or moral, rather than related to mere language.

Julius Caesar has been causing arguments for over 2,000 years. Suetonius concedes his virtues and genius, but fully understands why he was assassinated, and essentially suggests that he was asking for it. Petrarch wondered aloud whether we should remember Caesar as the military saviour of the Roman people, or the man who overthrew the Republic and instigated a bloody civil war. Even now, to claim Caesar as your inspiration is asking for trouble. Mantegna could not ignore the inherent political sensitivities of his chosen subject.

Intellectuals like Petrarch have always been wary of Caesar, and not merely because they prefer Cicero’s Latin. Yet Dante (1265–1321) placed Caesar among the virtuous pagans in his Inferno, and not in the company of the damned. Mantegna’s private attitude is surprisingly difficult to discern. Is he celebrating the triumph along with Caesar, or is he merely parading his own ingenuity and learning? The pageantry appears to be more important than the general himself, whose appearance in the final completed Triumph is something of an anti-climax. Is that by design, or has too much paint flaked off over the centuries for Julius Caesar to look as formidable as he once did?

Part of the problem with interpreting this ninth picture confidently is its poor state of preservation. Also, some sections of the Triumphs (notably in the upper-right corner of the seventh image) are unfinished. There is no documentary evidence that would explain certain anomalies in the design, or otherwise help us understand this series better. All we can do is study the pictures themselves closely, and try to guess what Mantegna’s intentions were.

Perhaps this series is best thought of as a kind of dream vision – the inevitable result of a lifelong obsession with armour, weaponry and the symbols of warfare. Mantegna must have had his imagination stoked by military parades and courtly theatricals at least as much as by his own archaeological and antiquarian studies: the soldiers he depicts seem mainly to be officers in expensive breastplates.

Petrarch might have indirectly inspired the Triumphs: after all, he inaugurated a tradition of vividly imagined fantasy parades in his allegorical poems the Trionfi (Triumphs, 1351–74), one of the most influential poetic sequences of the Renaissance. Their influence spilled over into real life: in Mantegna’s time, a trionfo signified a parade float in the Florentine dialect. For modern readers, Petrarch’s Trionfi are perhaps a little repetitive and ‘mediaeval’, unlike Mantegna’s Triumphs, which retain their freshness even though the colours have faded.

Mantegna’s Julius Caesar does not look obviously triumphant in his moment of triumph. But how are we to interpret this image when we can barely make out key details, like the once-legible Latin inscription at the centre? As with most discussions where Julius Caesar is involved, we inevitably project our own fixations onto the canvas, and put words in Mantegna’s mouth and thoughts in his head so that he reflects our most cherished preoccupations: either we reject the very idea of greatness, or else acknowledge it only when we can see a reflection of ourselves.

The sole surviving ‘autograph’ preparatory drawing for the Triumphs series was sold at auction in 2020 – for an enormous sum. Look at how hard Mantegna worked on these images. There is nothing casual or sloppy about them: every effect was painstakingly calculated after long meditation. That said, even Mantegna could not control his spectators’ reactions in the end. The best he could do was to entice you into a relationship with his work.

Your perception of the ninth Triumph might be altered somewhat by what would have been the tenth painting in this series, had Mantegna lived to complete it. The tenth image, which has been known since at least the time of Goethe (1749–1832) as The Senators, was familiar to generations of cultured people who never saw the Triumphs in person, but studied them in engravings. Perhaps the best copy of the long-lost original is now held by the Albertina Museum in Vienna.

Goethe thought these ‘Senators’ were in fact writers, or representatives of the teaching profession in some way; Andrew Martindale has more convincingly suggested that they are aides and secretaries following the general’s chariot. The truth is, we have no solid evidence either way. Do we favour Martindale’s learning and common sense, or Goethe’s brilliance and poetic genius, self-serving though his conclusions might have been on this particular subject? Whom would Mantegna prefer to immortalise, political advisers or more scholarly types? Or might Mantegna might have intended to show us senators after all?

A Classical Vision

Mantegna’s vision of a triumph is so captivating that no Roman-era depiction could possibly compete with it. Then again, the silversmiths responsible for memorialising the triumphal procession of Tiberius (7 BC) on a skyphos from the Boscoreale Treasure could take for granted that the people for whom it was made had some idea of what a triumphal procession looked like; an impressionistic or relatively symbolic representation would have served its purpose. A thousand years after the fall of the Roman Empire, a little more effort was required to bring such an event back to life.

Mantegna did for the Roman triumph what Michelangelo did for David: he created a new model of representation. Engravings and woodcuts of his images circulated around Europe; eventually they supplanted Petrarch’s Trionfi as the main starting point for artists and writers seeking to envision a triumphal procession. The Triumphs set a standard for historical accuracy that still seemed daunting in the mid-19th century, when the young Edgar Degas began contemplating a career as a history painter. Those who were unable to immerse themselves in the study of antiquity as Mantegna did were content to follow his example meekly and gratefully, and save themselves the trouble of reimagining the Roman triumph afresh.

A 1510 painting of Caesar’s triumphal procession owned by the University of Florida and currently attributed to Palma il Vecchio (1480–1528) is self-evidently copied from engravings; however, the artist has given himself licence to improvise freely on the Triumphs, just as Mantegna himself riffed on Roman sarcophagi in his Battle of the Sea Gods and Bacchanal prints. The result is a witty demonstration of independence by a painter who knew he could not compete with Mantegna for grandeur, so took his work in the other direction.

The most illuminating copy of Mantegna’s series is by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), who understood better than most others what Mantegna had managed to achieve. Rubens was far more gifted and imaginative than Mantegna; he was also a gentleman, and had the good manners to recognise his debt to his predecessor. His Roman Triumph (1630) in the National Gallery in London is worth contemplating at length: this is a tribute to Mantegna that implicitly criticises certain aspects of his work. When you look at this picture, a free imitation of the fourth and fifth Triumphs combined, consider what Rubens altered, and consciously decided not to copy.

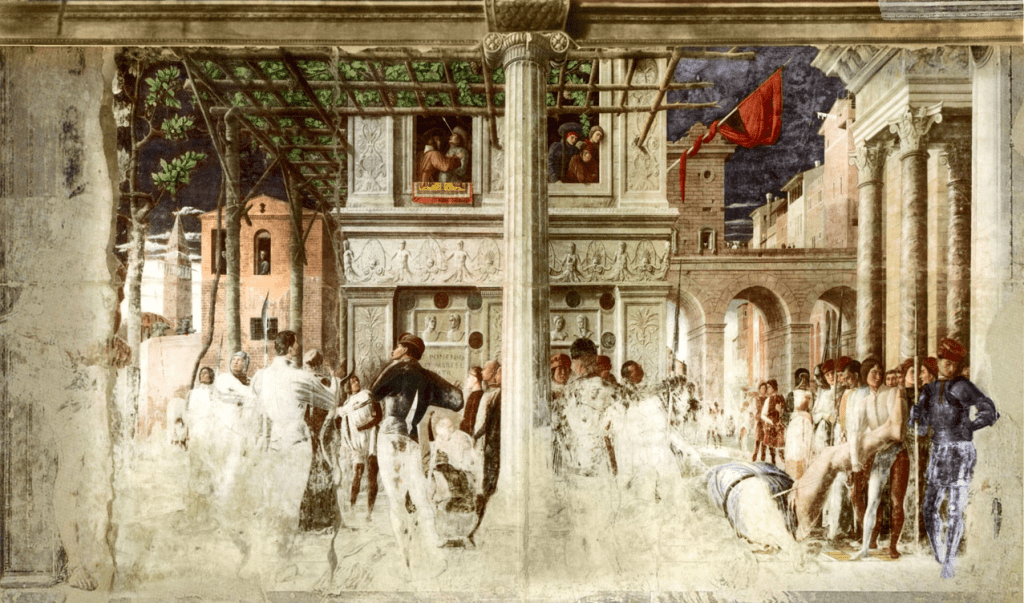

Mantegna’s last painting, The Introduction of the Cult of Cybele at Rome, draws largely on Livy, probably on Roma Triumphans, and possibly on Ovid and/or Appian, to tell the story of how the Romans transferred the cult of Cybele to Rome in 204 BC. Thanks to His Majesty King Charles III, this can be studied in close proximity to The Triumphs of Julius Caesar until Christmas 2025, when the Triumphs return home. The Introduction of the Cult of Cybele and the Triumphs are among the only paintings that can be considered genuine achievements of Renaissance humanism in their own right. Not even Rubens or Raphael, for all their learning and genius, achieved this.

Mantegna died on 13 September 1506; no artist since then has ever approached his sheer sympathy with Classical art, and the often-anonymous artisans who made it. He succeeded in bringing Pliny the Elder’s descriptions of long-lost ancient paintings to life – which is, on the face of it, a completely insane ambition. Yet his very pursuit of this madness is what made him great.

Scholars have argued for decades about whether Mantegna saw the Ara Pacis Augusti (The Altar of Peace of Augustus, consecrated on 30 January, 9 BC) during his extended visit to Rome (1488–90). This seems impossible: the first fragments of the Ara Pacis were discovered in 1568, over half a century after the artist’s death. Yet some sections of theTriumphs look exactly like parts of the Ara Pacis. This has led some scholars to concoct elaborately convoluted explanations for this coincidence. It has not yet dawned on them that Mantegna’s depth of sympathy with the ancients made this possible. In this way, he sets an example for every artist, and writer, who seeks inspiration from the classical world. He was unafraid to seek glory, or bask in his own triumph – briefly, before getting back to work.

Jaspreet Singh Boparai cultivates the muses.

Further Reading

Andrew Martindale’s 1979 study The Triumphs of Caesar by Andrea Mantegna has been mentioned above. For now this remains the best work in English on this subject.

The quickest way to learn about Mantegna more generally (or indeed any other Old Master) is to track down the catalogues of major exhibitions at great museums (in London, Paris, Rome, New York, Vienna, and so on) and study them intently. Take good notes on the bibliographies, and try to gain a sense of which scholars you trust. Any art historian who writes in opaque or otherwise ugly language, or has mistaken him- or herself for a ‘literary essayist’, or seems to have an inadequate grasp of Latin, is not to be taken seriously. Art history has long proved attractive to failed writers; learn how to spot them, and keep a safe distance, lest their miasma infect you. Bad poetry can be contagious.

Also contagious are the current intellectual standards of Ivy League universities. Let us not mention any names, except to suggest that someone who contributed an essay to the otherwise-excellent catalogue of the Mantegna and Bellini exhibition at the National Gallery (October 2018 – January 2019) ought to be taken aside and gently informed that undergraduate lectures in art history do not always provide a sound basis for pronouncements on Systematic Theology, or the history of the Catholic Church. When the only Christian text you know is The Golden Legend (in translation) it is time to resume catechism lessons.

Once you are bored of looking at exhibition catalogues and heavy art books, start finding ways to examine pictures in person. You already know that photographic reproductions of paintings (and sculptures and buildings) are always inadequate; the same turns out also to be true for reproductions of prints and drawings. Not everybody has the good fortune to live near the Louvre, the Uffizi or the Art Institute of Chicago; but most of the people who do take their opportunities for granted, and waste them.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Carolina Mangone’s book Bernini’s Michelangelo (Yale UP, New Haven, CT, 2020) is an interesting and informative exploration of Bernini’s relationship to his hero/rival; it is possible to disagree with Mangone on many key points and conclusions whilst learning a great deal from her work. |

|---|