An Antigone explainer

The Second Vatican Council (1962–5), or ‘Vatican II’ as it is commonly known, changed the Roman Catholic Church in a number of ways; of all the reforms that followed in its wake, perhaps the most controversial involved the Mass, the bloodless sacrifice that is the centre of Catholic worship. Faithful members of the Church are obliged to take part in this liturgical ritual every Sunday, and on Holy Days of Obligation such as the Feast of the Annunciation, Christmas Day and Easter. For nineteen centuries, the overwhelming majority of Masses were in Latin; since 1970, most Masses have been celebrated in local vernacular languages, in an altered rite.

The Catholic Church has three sacred languages: Hebrew, Classical Greek and Latin. All three languages have a special status in the Gospels: a sign written by Pontius Pilate reading “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” in Latin, Greek and Hebrew was affixed to the cross on which Jesus was crucified (John 19:19–20). Latin has always been the language of the Catholic liturgy, of many of the important hymns and prayers, and of the Church’s laws, doctrines and teaching statements, as well as its correspondence and official documents. For this reason it is the most important of the Church’s sacred languages. Latin has been used by the Catholic Church since the time of the Emperor Nero (r. AD 54–68): the first pope, St Peter, who was martyred at Rome at some point between AD 64 and 68, is presumed to have instituted the first Masses in Latin.

The Nicene Creed is one of the only sections of the ancient Mass that can be securely dated; but nobody quite knows how or when the Latin version was produced. This statement is a declaration of what Christians believe: the original Greek text was ratified in AD 325 and revised in 381. Otherwise, the ritual of the Mass changed imperceptibly over the centuries; indeed there is reason to believe that the ritual of the Roman Rite was already fixed and relatively long-established by the time Constantine the Great (AD 272–337; r. 306–37) became Emperor at Rome.

Thanks to the Dumbarton Oaks Mediaeval Library series (Harvard University Press), it is now possible even for readers without Latin to read the work of the 9th-century liturgy expert Amalar of Metz (775–850). The Catholic Mass of the 8th and 9th centuries turns out to have been more or less indistinguishable from the Mass up to the mid-20th century, in its calendar, its rituals, its vestments, the specific prayers used. Many Catholics erroneously believe that the Latin Mass as it was known before Vatican II was instituted only after the Church’s Council of Trent (1545– 63).

Any time you enter a Catholic church that was built before the mid-20th century, you are experiencing a building that was created for the old Latin Mass; whenever you listen to Masses or choral pieces by composers from Palestrina (1524–96) to Poulenc (1899–1963), you are enjoying music that was meant to accompany ancient Latin liturgies. Thus it is curious to think that this ritual changed so radically over fifty years ago.

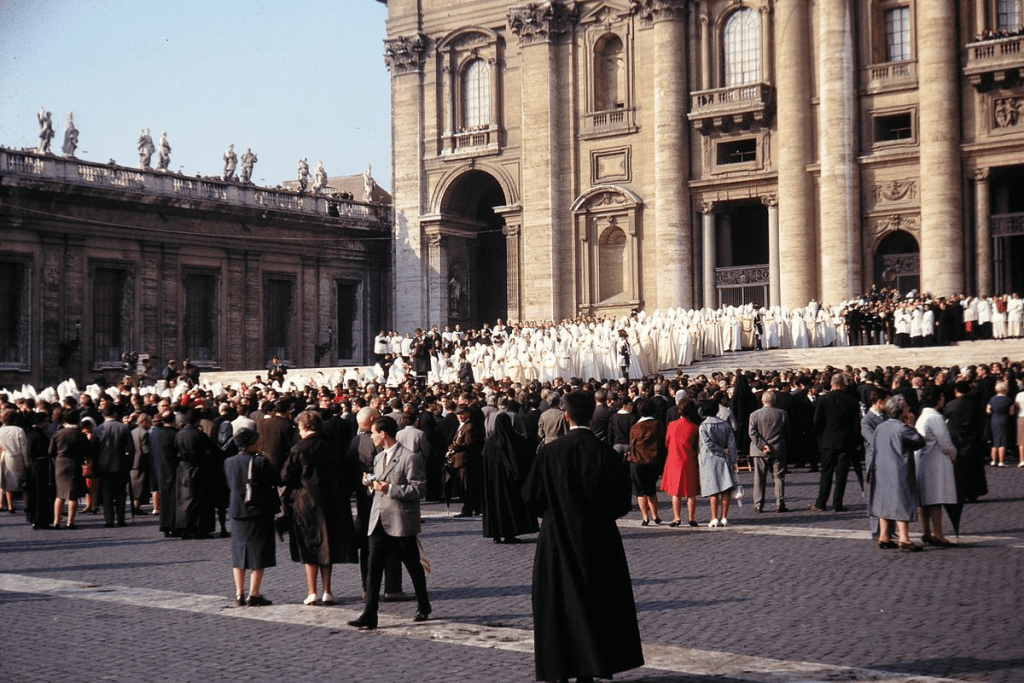

On 7 March 1965, Pope Paul VI (1897–1978; r. 1963–78) celebrated the first-ever Catholic Mass in the Italian language, in accordance with liturgical reforms suggested during Vatican II, in the otherwise-unremarkable Chiesa di Ognissanti in Rome, which was completed in 1920. That day, the pope openly spoke of “sacrificing” the Church’s principal sacred language:

This Sunday marks a memorable date in the spiritual history of the Church, because the spoken vernacular officially enters liturgical worship. The Church has considered this measure right and proper… in order to render its prayer intelligible and make it understood. The welfare of the people demands this… to make possible the active participation of the faithful in the public worship of the Church.

The Church has sacrificed her own language, Latin – a sacred, sober, beautiful language, highly expressive and elegant. She has sacrificed the traditions of centuries and above all she sacrifices the unity of language among the various peoples, in homage to this greater universality, in order to reach all.

A new Mass, designed largely by Mgr Annibale Bugnini CM (1912–82), Titular Archbishop of Diocletiana, was imposed on the Church worldwide in stages, with Archbishop Bugnini’s final text officially published in Latin on 26 March 1970. Bishops were ordered to approve vernacular-language translations no later than 28 November 1971. The entire Church Calendar was also revised. In most of the world, the ancient Latin Mass disappeared overnight.

There is no space here to describe all the differences between the ancient and the new ritual; suffice it to say that Archbishop Bugnini’s revisions to the liturgy were not universally popular. Perhaps the most important criticism was published on 25 September 1969 by Alfredo Cardinal Ottaviani (1890–1979), Secretary of the Holy Office: an English translation of the text will be found here.

Those who objected to Bugnini’s new ritual and the worldwide suppression of the old Mass were not very well-organised as a ‘resistance movement’; the French historian Yves Chiron tells their story in Between Rome and Rebellion: A History of Catholic Traditionalism (June 2024). Another important resource is the 2023 collection The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals: Petitions to Save the Ancient Mass from 1966 to 2007, edited by Joseph Shaw, Chairman of the Latin Mass Society of the United Kingdom. Shaw’s collection demonstrates how many of the figures who made the most noise about Archbishop Bugnini’s innovations, and objected with particular vehemence to the disappearance of Latin, were not churchmen or theologians, but writers and musicians; what is interesting is how few of them seem to have been practising Catholics.

The first petitions (1966–71) inevitably feature famous Catholic novelists: Evelyn Waugh (1903–66), Graham Greene (1904–91), Nobel Prize laureate François Mauriac (1885–1970) and Nobel Prize nominee Baroness Gertrud von Le Fort (1876–1971). There are also liberal Catholics like the theologian Jacques Maritain (1882–1973) and ex-Catholics including the great short-story writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) and Robert Lowell (1917–77), one of the finest 20th-century poets. But they are outnumbered by a diverse group that includes: two Anglican bishops; agnostic Anglicans such as the composer Benjamin Britten (1913–76) and the poet W.H. Auden (1907–73); atheist ex-Anglicans (the celebrated man of letters Cyril Connolly, 1903–74); the ex-Lutheran atheist film director Carl Theodor Dreyer 1889–1968 – one of at least two atheists on the list who made great Christian movies, the other being Robert Bresson, 1901–99); Yehudi Menuhin (1916–99), the violinist who was not only from a Jewish background, but came from a long line of rabbis on his father’s side; and two English Communist sympathisers. Some signatories of these early petitions are still alive, including the pianist and conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy.

In general, Pope Paul VI was receptive to these petitions; the most famous was published on 6 July 1971 in The Times of London. The text will be found here.

Among 105 names that remain well-known today, classicists will recognise two famous Oxford Hellenists: Dame Iris Murdoch (1919–99), who is better-known today for her Booker-Prize-winning 1978 novel The Sea, The Sea than her still-stimulating reinterpretations of Plato and Aristotle; and Sir Maurice Bowra (1898–1971), who died two days before the petition was published. Antigone readers of course know Sir Kenneth Clark (1903–83), the art historian responsible for the TV series Civilisation (1969). The letter pleaded with Pope Paul VI to allow the Catholic Church’s traditional Latin Mass to carry on being celebrated in the British Isles. Most of the signatories appreciated the Latin liturgy in purely aesthetic terms, and understood its historical importance far better than many churchmen and theologians.

The Cardinal-Archbishop of Westminster presented this petition to the Holy Father, who read the letter and exclaimed “ah, Agatha Christie!” He loved reading murder mysteries, and recognised among the signatories the name of the novelist who created the detectives Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot. On 5 November 1971, Pope Paul VI officially granted permission to the Catholic Church in England and Wales to continue to use the ancient form of the liturgy, under certain conditions. This exception to what was then a worldwide ban on the Latin Mass became known as the “Agatha Christie Indult”.

In 1984, Pope St John Paul II granted a further worldwide ‘indult’ for certain groups who wished to celebrate the Church’s traditional liturgies; finally, on 7 July 2007, Pope Benedict XVI issued an apostolic letter of the sort known as a motu proprio (the Catholic Church’s equivalent of an Executive Order signed by the President of the United States) called “Summorum Pontificum”, which made clear that under canon law, permission to celebrate the traditional Latin Mass had never been abrogated.

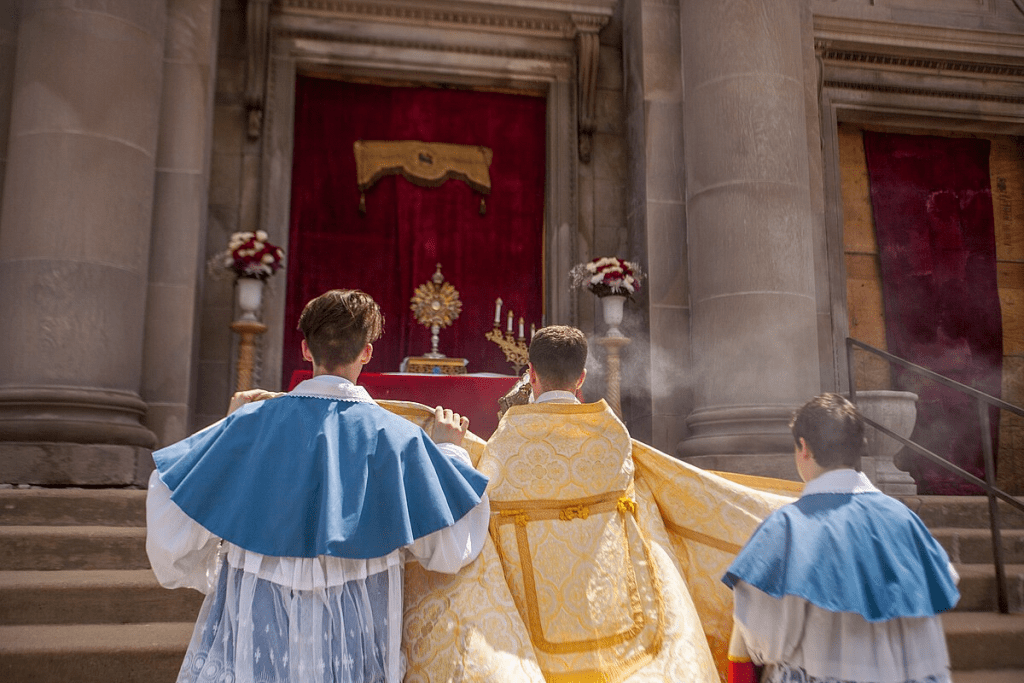

Latin Mass communities have unexpectedly grown and flourished since then, and proved noticeably popular among young people, so Catholics were understandably shocked and dismayed when the Holy See unexpectedly began to reimpose restrictions on the ancient rite in 2021. The Latin text of the apostolic letter (18 July 2021) that promulgates these restrictions is worth studying closely.

Semi-annual celebrations of the Latin Mass that have been organised since 1972 at Westminster Cathedral in London were banned in autumn 2023. Since Easter, rumours have emerged of moves towards a total suppression: the Latin Mass might be in favour among an ever-multiplying proportion of the Catholic faithful, but the Vatican seems increasingly unfriendly, for whatever reason. The composer Sir James MacMillan decided to organise a new petition in support of the Mass; this was published earlier this week in The Times on 3 July 2024. The text of the letter can be read here, in a press release from the Latin Mass Society of the United Kingdom.

As with the letter that led to the “Agatha Christie Indult”, there has been an unexpected range of influential signatories. Macmillan writes:

The people who have signed this letter are an impressively mixed bunch! Catholics, Protestants, Jews, agnostics atheists – all convinced that the Traditional Latin Mass is a thing of great beauty, wonder and awe, and a profound shaper of our culture, one way or another over the centuries. I stand with them in my appreciation of the form – ‘a cathedral of text and gesture’, which has given rise to great music and poetry through the ages. But it is as an observant and loyally practising Catholic that I wrote my cover article for The Times. If Rome were to do what is rumoured, it would be grossly unjust and make an utter mockery of ‘synodality’. And many observers outside the Church, in these difficult days of ideological and political tension, see this now as an issue of religious freedom. It is surely a mark of diversity, inclusion and equity that the Church can celebrate different rites – the Old Dominican rite, the liturgy of the Ordinariate, the rites of our eastern co-religionists, the Novus Ordo and, God willing, the Traditional Latin Mass.

In the interests of full disclosure, we should note that Sir James MacMillan composed an oratorio, Fiat Lux, for which the libretto was written by Antigone contributor Dana Gioia. But we note the presence of other friends on the list of signatories, not least the historian Tom Holland. We also have a member of the royal family (Princess Michael of Kent), a billionaire (Robert Agostinelli), the most famous living opera singer (Dame Kiri Te Kanawa); the best-known, most successful composer of musicals alive (Andrew Lloyd-Webber); the peer who wrote the series Downton Abbey (Julian Fellowes). Rather than list every name here we will instead thank them all collectively for helping to preserve this beautiful ritual, whose sacred importance extends far beyond the aesthetic.

Further Reading

Yves Chiron is perhaps the most important living Catholic historian: his three most recent studies to have been translated into English, Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy (2018), Paul VI: The Divided Pope (2022) and Between Rome and Rebellion: A History of Catholic Traditionalism (June 2024) are all essential for understanding the history of the so-called ‘traditional Latin Mass’ since the 1960s.

There are surprisingly few good books available in English on The Second Vatican Council; the best ones all seem to be in French. Shaun Blanchard and Stephen Bullivant have written Vatican II: A Very Short Introduction (2023), which is not only excellent and miraculously concise, but has a very useful bibliography. Among fuller accounts, Roberto de Mattei’s magisterial Il Concilio Vaticano II: Una storia mai scritta (2010; translated into English as The Second Vatican Council: An Unwritten Story, 2012) is indispensable.

The single most readable narrative history remains The Rhine Flows into the Tiber: A History of Vatican II by Fr Ralph Wiltgen SVD (1921–2002), first published in 1967, and reissued in 2014 as The Inside Story of Vatican II: A Firsthand Account of the Council’s Inner Workings.

Pope Benedict’s three books on Vatican II reward close study. Theological Highlights of Vatican II (1966; reprinted 2009) is the work of a radical reformer; The Ratzinger Report: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church (with Vittorio Messori, 1985) provides sober re-evaluation; and the rueful recollections in Milestones: Memoirs 1927-1977 (1998) of Cardinal Ratzinger, as he then was, show just how far his thinking developed after his fortieth birthday.

Perhaps the best available technical book on the Latin liturgy is Fr Michael Fiedrowicz’s The Traditional Mass: History, Form and Theology of the Classical Roman Rite (2020).

The German novelist Martin Mosebach has written the most attractive recent introduction to the usus antiquior: his brilliantly evocative 2002 essay collection Häresie der Formlosigkeit: die römische Liturgie und ihr Feind (translated as The Heresy of Formlessness: the Roman Liturgy and Its Enemy) was republished in English in 2018. This is arguably the central Catholic literary masterpiece of the last fifty years.