Jamie Collings

“Among the Greeks the answer of the Delphic Apollo is well known: ‘Man, know yourself.’ So also Solomon, or rather Christ, says in the Canticle, ‘If you do not know yourself, go forth’.”

William of Saint-Thierry, De anima, Prologue, 1.105[1]

The 12th century has long been regarded as a watershed for the Classics in the medieval west. As medieval society became richer, more populous, densely urbanised, and better educated – in a word, more developed – the role that materials from the Classical past played in intellectual culture changed and grew. In Bologna, and across Italy, Roman Law was revived by the rediscovery of the Corpus Iuris Civilis and incorporated into handbooks such as Gratian’s Decretum. In Spain and Italy, translators including Constantine the African, Burgundio of Pisa, Gerard of Cremona, Dominicus Gundissalinus, and Petrus Alfonsi invigorated occidental knowledge of Classical science, while the introduction of the Aristotelian corpus eventually supplied the foundation for the emerging world of scholastic theology.

Equally significant, but perhaps less well known today, was the rebirth of Classicising literature. Latin epic blossomed, with works like Walter of Châtillon’s Alexandreis, Alan of Lille’s Anticlaudianus, John of Hauville’s Architrenius, and Joseph of Exeter’s Ylias all testifying to the heightened Latinity of the age, as does the flowering of Ovidian commentary at Orléans, or Neoplatonic commentary at Chartres. Whether esoteric or influential, these projects demonstrated that the Classics now rested near the heart of the intellectual, cultural, and literary renewal of the age.

However, it was also the case that the main groups who most frequently utilized the Classics – Christian clergy in either the monasteries or the schools – were also the most critical of them. Monasticism, whether in its ‘traditional’ Cluniac or Benedictine forms, or those of the ‘reform’ oriented Cistercians, Premonstratensians, and Carthusians, held that transcending human knowledge was not only possible, but the very purpose of religious life. The mind was an inner space to be filled with fitting images in the service of spiritual advancement.

Deliberative reading of scripture (lectio), the creation of mental exercises to heighten the spiritual sense (meditatio), and eventual contemplation of divine things (contemplatio) were to be reinforced with the behavioural rhythms of liturgy, prayer, and manual labour. The product of this process, sapientia (roughly, “wisdom”) was deemed superior to the clumsy and limited scientia (or “knowledge”) of ordinary perception and cognition. Natural knowledge of created objects, which included human knowledge itself and thereby the Classics, was therefore deemed an unworthy subject for proper monastic religio.

The work of Guibert of Nogent (c.1055–1124) provides a good example of this concern that writing should facilitate sapientia rather than mere scientia. He was a pioneer in the spiritual revival of 12th-century monasticism, and, sure enough, we find him citing Sallust, Lucan, Terence, and especially the “poets”. Yet in his Monodies, one of the chapters is titled “My flirtation with poetry. I am saved by Scripture”:

Meanwhile, I had fully immersed my soul in the study of verse-making. Consequently I left aside all the seriousness of sacred Scripture for this vain and ludicrous activity. Sustained by my folly I had reached a point where I was competing with Ovid and the pastoral poets and striving to achieve an amorous charm in my way of arranging images and in well-crafted letters. Forgetting the proper rigor of the monastic calling and casting away its modesty, my mind became so enraptured by the seductions of this contagious influence… that I began to use a few slightly obscene words and to compose little poems entirely bereft of any sense of weight and measure, indeed shorn of all decency.

Monodiae, 1.17[2]

As Guibert saw it, he had failed to use these Classical materials correctly. His motives had become corrupt; and accordingly, he had neglected truth for frippery, humility for vanity, and divine love for eroticism – in short, he had been seduced by worldliness. The schoolman turned Cistercian abbot William of Saint-Thierry (c.1075–1148) argued that, in this regard, Ovid was a particularly dangerous writer:

For foul, fleshly love once had teachers of its foulness: persons so skilful and effective in having being been corrupted and corrupting others that the teacher of the art of loving [Ovid] was forced by the lovers and companions of foulness itself to recant what he had praised… he earnestly applied himself to change its natural power into a kind of insane licentiousness by some undisciplined approaches and urged it towards a licentious insanity by superfluous incitements to lust.

On the Nature and Dignity of Love, or, the Anti-Naso, Prologue, 2.[3]

Yet even Ovid could be used with the right training and a sapiential mental state. As Jean Leclercq has argued, no 12th-century thinker used more Ovidian language than the ultra-monk himself, Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153). His commentaries andthose of his Cistercians On the Song of Songs (itself ostensibly an erotic text about the marriage bed) draw extensively from gustatory and sensual language with an unmistakeably Ovidian relish. Yet, these commentaries were considered the gold standard of piety.

The key point is that Bernard’s sensual language was understood with regard to the intention with which he employed it, or as we say, it is to be understood intentionally. Having assumed a specific behavioural and intentional posture, one would only hear Bernard’s affective incitements towards divine love, not about nature, nor the pleasures of the marital bed, and least of all Ovid.

Using rhetorical tools extracted from Classical materials to incite believers to renounce worldly preoccupations (such as the Classics) was ubiquitous, and indeed, praiseworthy. Similarly, figures from Classical antiquity could be appropriated as cautionary examples. A tale from a manuscript from the Abbey of Aulne provides a good example of this approach. In the story, a clerk’s friend dies, then his spirit appears to the clerk. Instead of asking religious questions, the clerk merely wants to know the meaning of several Vergilian verses. The spirit departs, and returns with Vergil’s scathing response:

Magister autem quid Yirgilius respondisset sciscitatus est. Ad quem mortuus respondit : “Yirgilius, mihi sciscitanti super hoc quod mihi iniunxeras : “Quoniam stultus es et stulta quaes- tio tua”. Et scias pro certo, nisi citius, uanis auctorum fabulis et artium liberalium friuolis abrenuntians, euangelicae ueritati firmiter adhaeseris, cum ipso, citius quam speras, in aeternae perditionis interitum perennabis”. Magister autem, per aquam benedictam salutem recuperans, saeculo penitus abrenuntiauit.

Moreover the master asked what Virgil had answered. To him the dead man responded: “Virgil, replying to me about that which you had charged me, said: ‘How stupid you are, and how stupid is your question.’ And know this for certain: unless you renounce the vain stories of the authors and frivolous liberal arts, cleave firmly to the truth of the gospels, sooner than you’d hope, you will endure the ruin of eternal perdition with him.” And the Master, recovering his health through the holy water, inwardly renounced the world.

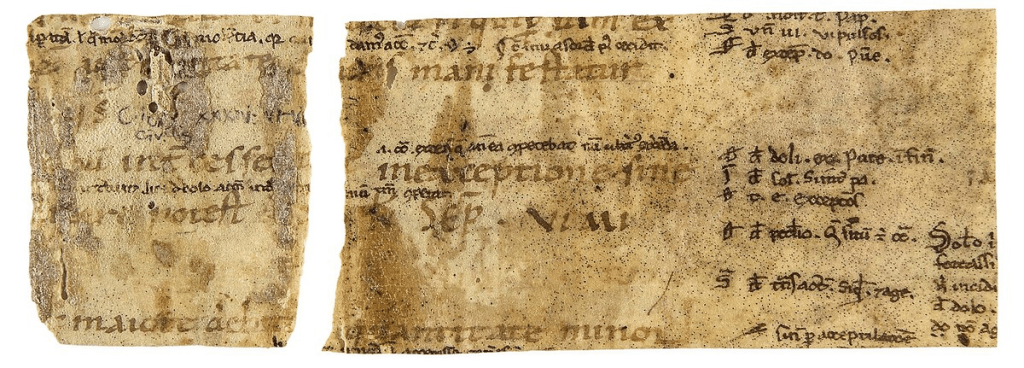

Aulne Manuscript, Brussels, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, II 01064 (V.d.G. 1450)[4]

This exemplum is not arguing that those who use a phrase from Horace or Cicero will be condemned to perdition, but rather those who abandon the spiritual in favour of the worldly. In a similar vein, the schoolmen (those who taught outside of the confines of a monastery), either those who lived a quasi-monastic life such as the Victorines and Augustinians, or the masters of Chartres, Tours, Paris, and Reims, anticipated that only a sapiential pattern of life would facilitate and provide warrant for human inquiry.

Although schoolmen understood that Classical materials could perhaps reinforce and even expand the epistemic boundaries of Christian belief, they were concerned that such knowledge would redirect the hearer’s mental activity away from spiritual goals. Thus, when schoolmen cultivated the fruits of scientia they did so within a moral framework based on patristic authority, moral behaviour, reputatio, and the testimony of psychological experience.

But the pagan ancients had been unwilling or unable to call upon divine assistance to expand their feeble human capacity. Bereft of sapientia, they had contented themselves with the rudiments of visible truth. Accordingly, works which united and affirmed the unity, truth, and beauty of the patristics or of scripture (and shut out the distracting chatter of the pagans) were often circulated more widely and studied more than Classicizing or Classical works. For example, the Sentences and Glossa ordinaria of Peter Lombard (c.1096–1160) were some of the most popular texts of this age and of the entire Middle Ages. Yet, Peter himself eschewed Classical knowledge in favour of patristic and scriptural synthesis:

But a sufficient knowledge of the Trinity cannot and could not be had by a contemplation of creatures [created objects], without the revelation of doctrine or inner inspiration. So it was that those ancient philosophers saw the truth as if through a shadow and from a distance, lacking in insight into the Trinity, as was the case with Pharaoh’s magicians in the third plague. And yet we are aided in our faith in invisible things through those things which were made.

Lombard, Sentences, Book I, Distinction III, Ch 1.9[5]

Conversely, the primary failing of ancient authors was that their intentionality was obviously directed towards worldly pursuits. By focusing on coming to know the world-in-itself, they had denied themselves the very capacity of reason which they had hoped to exercise. A soul wholly subsumed into such a state could not even correctly perceive the finite objects which had begun the process of its corruption:

Deluded by this error [pride], therefore, the sorely imperceptive soul gives itself over wholly to the vice of curious inquiry [curiositas]. And by degrees, as the disease increases… ultimately reaches a condition in which, with everything it sees, it tries either to mispresent it openly, or to interpret it unfavourably.

Hugh of St Victor, De arca noe morali 3.10[6]

Therefore, if one avoided this curiositas which characterized pagan thought (namely, prideful intellection of the fallen material world-in-itself), one could avoid damaging the rational soul and thereby use Classical materials quite freely. John of Salisbury (c.1110–80) wanted to talk about scientia – namely, the correct means of knowing the created world and acquiring human knowledge. This required Classical materials, and sure enough he made extensive use of Greek, Ciceronian, and Platonic knowledge. But he was careful always to give precedence to sapientia:

It was for this reason that our forebears referred prudence or knowledge to familiarity with temporal and sensible things, but understanding or wisdom to familiarity with spiritual things. The usual term in the human context is knowledge [scientia], in the divine, wisdom [sapientia]… Both in human and in divine matters faith is most necessary… It stands midway between opinion and knowledge, since it strongly asserts a thing as certain, but does not through knowledge attain to certitude concerning it. Hence the observation of Master Hugh: Faith is willing certitude concerning absent things, stationed above opinion but below knowledge. But here the word knowledge is used in a wider sense, being extended as far as the comprehension of things divine.

Metalogicon, 4.13[7]

On the one hand, John cedes a certain priority to sapiential knowledge. On the other he is making prudentia and scientia a necessary feature of it. Prudentia is framed as a component of scientia, and scientia an assistant to sapientia. Thus without prudentia there can be no judgement; without judgement, no knowledge of objects – and, without said objects, what exactly is there to transcend with sapientia? But, John’s intentions are plainly grounded in (or are at least respectful of) sapientia; he is not involved in vainglorious intellection of the material world-in-itself. John is therefore avoiding prideful intellect, and is not guilty of curiositas.

Having taken up the correct intentional posture, and avoided curiositas, one could set about using Classical thought more completely. Precisely because the ideas in Classical texts lacked deference to the Christian truth, it was fine to update their ‘incomplete’ ideas, in part to highlight the insufficiencies of those pesky pagans. For example, Neoplatonism or Platonism were not deemed offensive if done correctly. Many monastics and schoolmen, like Isaac of Stella (c.1100–70), Alan of Lille (c.1128–c.1202), Thierry of Chartres (d.1155), William of Conches (c.1090–1160) or Abbot Suger of St. Denis (c.1080–1151) made extensive use of Platonism and Neoplatonism. Their Neoplatonism focused on symbolic themes such as luminary imagery, the orderliness of the cosmos, and the primacy of human reason. And while many of these thinkers faced some censure and criticism, they were certainly never ostracized.

It was hard enough to distinguish patristic authors from Neoplatonists – especially when many patristic authors were, in effect, Neoplatonic philosophers. Bernard Silvestris was an eminent example of this 12th-century trend. His works, such as the Cosmographia, sought to analyse nature through a Platonic lens; but one grounded in the fruitive model of the Christian cosmos, and which framed the antique world as an Old Testament which Christianity had fulfilled. Such an approach was highly respectable, and influential. In fact, the Cosmographia was read before the Cistercian pope Eugene III in 1147, with Eugene himself presented as the most recent measure in this providential design:

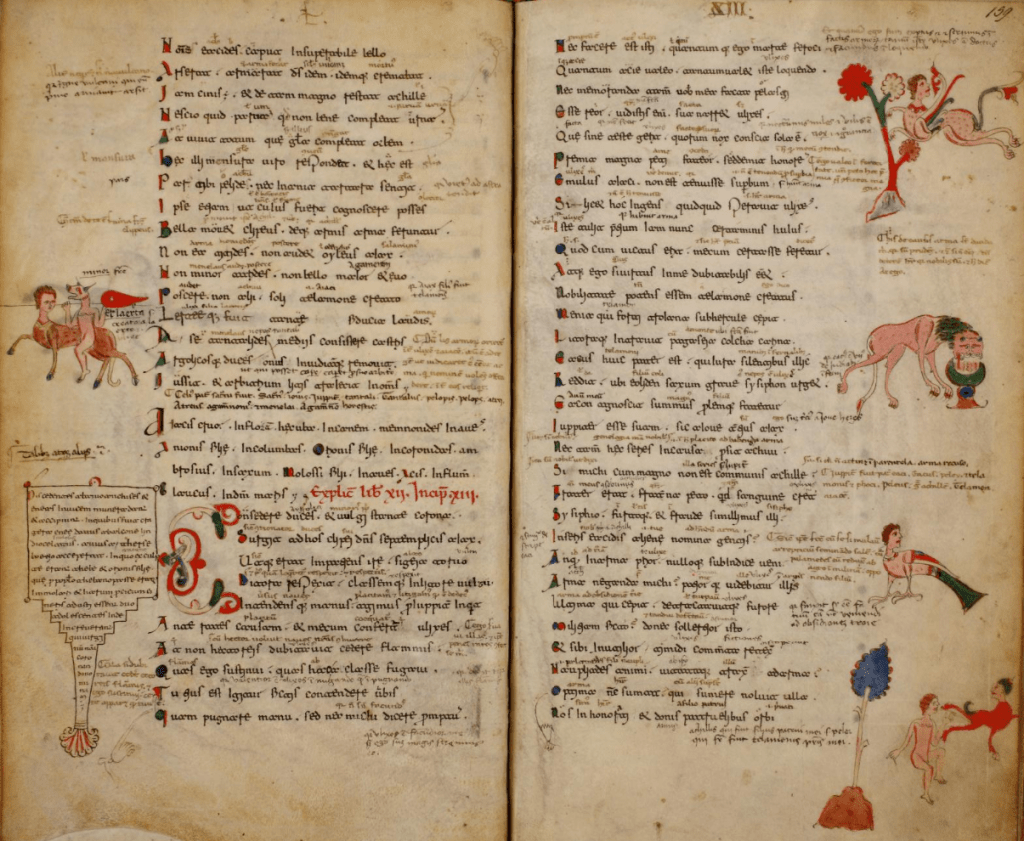

That sequence of events which long ages and the measured course of time will unfold appears first in the stars… Among the stars are Codrus’ poverty, Croesus’ wealth, the unchastity of Paris, Hippolytus’ modesty. Among the stars are the grandeur of Priam, the boldness of Turnus, Odyssean cleverness and Herculean strength. Among the stars are the boxer Pollux, Tiphys the helmsman, Cicero the orator, and the geometer Thales. In the stars Virgil composes with grace… Plato intuits the principles of existence, Achilles fights, and the generous hand of Titus pours forth riches. A tender virgin gives birth to Christ, at once the idea and the living form of God, and earth possesses true divinity. Divine munificence bestows Eugene upon the world, and grants all things at once in this sole gift. Thus the Creator works, that ages to come may be beheld in advance, signified by starry forms.

Cosmographia, Megacosmos 3.37-58[8]

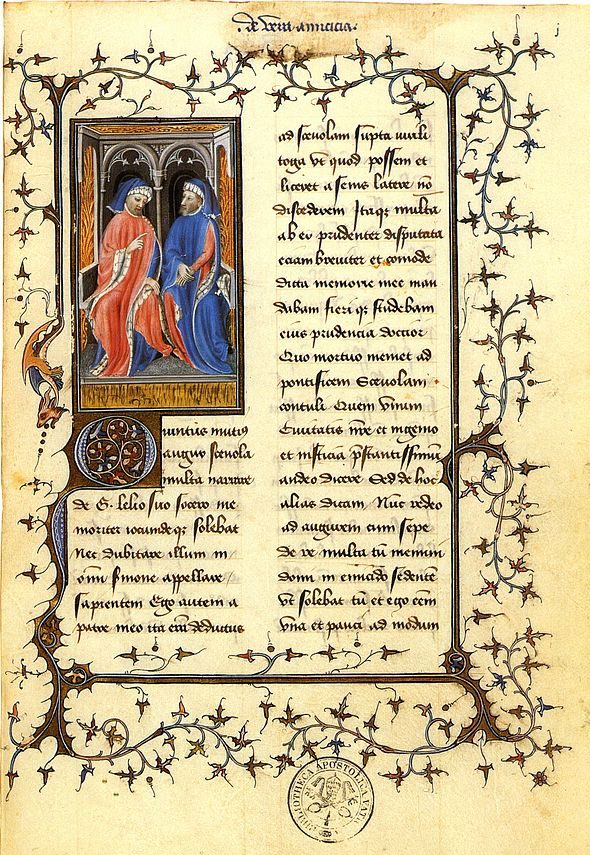

While Bernard Silvestris was busy reframing the Rhone as the Eridanus, more broadly even, entire social concepts were lifted from Classical models and remade. Aelred of Rievaulx (1110–67), a notable Cistercian abbot, penned an entire treatise on friendship drawn extensively from Cicero’s De amicitia:

But since the honeycomb of holy scriptures began to drip some its sweetness on me and the mellifluous name of Christ made its claim on my affection, anything I read or hear that lacks the salt of heavenly writings and the seasoning of his sweetest name, however subtle and eloquent is neither delicious nor clear for the friendship that ought to exist among us should begin in Christ, be preserved according to Christ, and have purpose and usefulness with reference to Christ. Obviously, Cicero did not know the virtue of true friendship, since he was completely ignorant of its beginning and end, namely Christ.

Spiritual Friendship, 1.7[9]

Aelred was understood to be demonstrating the supremacy of the Christian over the Classical; not making the former dependent on the latter. The obvious deficiencies of pagan friendship, for Aelred and his readers, were enough to establish a clearly sapiential intentionality. Aelred himself notes that precisely because Cicero’s definition of friendship works for pagans (and even for Jews) it must obviously lack truth. Only through Christ, whose spirit suffuses all legitimate social bonds, could real friendship exist. Entire fields of Classical enquiry could be interpreted through this lens of “obvious superiority” and thereby achieve acceptability.

In this way, medical texts became a favourite, with more than 550 surviving from the 12th century. Churchmen were deeply interested in medicine; indeed, monasteries and clerical foundations acted as the hospitals, retirement homes, and poorhouses of the period. But many were interested in medical texts for spiritual reasons, and these spiritual reasons justified their broader usage. Augustine had neither resolved how exactly the incorporeal substance of the soul could interact with the corporeal substance of the body, nor reconciled his earlier anti-corporeal thought with his later more positive approach. As a result, freshly translated medical texts appeared to offer a way to explain how the corporeal physical body, vis animalis, and the rational soul could interact – without contradicting patristic authority:

If, perhaps under divine prompting, you were not loathe to write us an accurate letter about the structure of the human body, you would receive something written in return from us. You could write about how the soul gladly assumes the body as the instrument of its activity and enjoyment.

Isaac of Stella, abbot, to Alcher of Clairvaux, physicus and monasticus[10]

There are, of course, so many Classical fields in the 12th century – of medicine, literature, law, and political theory – that a short survey such as this could not hope to cover all the specifics of their reappropriation. I have only touched on a few authors, whom I feel best explain the central paradox of the period: that a religious culture driven by ideas of spiritual reform was able, albeit tentatively, to embrace the fruits of pagan antiquity. By establishing strict moral guidelines, strong intentionality, and a sense that new materials would have to be superseded by the Christian ethos, Classical materials were used far more widely than one might expect – even by thinkers who otherwise inveighed against them.

A better understanding of how this society dealt with the Classics may intrigue those who wish to broaden their conceptual palates. Indeed, 12th-century poetry and epic, Neoplatonic and philosophical works, sermons, Classical commentaries, and devotional treatises are all most worthy of our time and attention. They are, in fact, the fruits of a society which lived, taught, and thought in Latin as a living language.

Jamie Collings is a PhD student at the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of Toronto. His research focuses on the culture and society of the High Middle Ages, particularly on varieties of monasticism, historiography, Italian history, and the medieval church.

Further Reading

For the sake of accessibility, I have used English translations of texts throughout this piece. However, I have also supplied references to Latin versions for those who may wish to go a bit deeper. For the Latin text (wherever feasible) I have drawn from a modern edition, rather than from older compilations like the Patrologia Latina which are much less accessible to a casual reader. Wherever possible, I have supplied a dual English and Latin reader, for example, a Dumbarton Oaks edition of the text. For the sake of brevity, I have only included texts in the bibliography which I have cited directly.

Aelred of Rievaulx, Writings on Body and Soul. Edited and translated by Bruce L. Venarde. Dumbarton Oaks 71 (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 2021).

Bernardus Silvestris, Poetic Works. Edited and translated by Winthrop Wetherbee. Dumbarton Oaks 38 (Harvard UP, Cambridge, MA, 2015).

Guibert of Nogent, A Monk’s Confession: The Memoirs of Guibert of Nogent. Edited and translated by and Paul J. Archambault (University Park: Pennsylvania State UP. University Park, PA, 1996).

Guibert of Nogent, Guibert de Nogent: histoire de sa vie (1053–1124). Edited by Georges Bougin (A. Picard, Paris, 1907).

Hugh of St. Victor, Selected Spiritual Writings. Translated by a Religious of C.S.M.V. (Faber and Faber, London, 1962).

Hugh of St. Victor, De archa noe. Edited by P. Sicard. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis CLXXVI (Brepols, Turnhout, 2001).

Isaac of Stella, William of Saint-Thierry, and Alcher of Clairvaux, Three Treatises on Man: A Cistercian Anthropology. Edited and translated by Bernard McGinn (Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, MI, 1977).

Isaac of Stella, Lettre Sur L’ Âme, Lettre Sur Le Canon De La Messe. Edited by Elias Dietz and Caterina Tarlazzi. Translated by Laurence Mellerin and Robert Favreau. Sources Chrétiennes 632 (Les Éditions du Cerf, Paris, 2022).

John of Salisbury, Metalogicon. Edited and translated by J.B. Hall (Brepols, Turnhout, 2013).

John of Salisbury, Iohannes Saresberiensis: Metalogicon. Edited by J.B. Hall. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis XCVIII (Brepols, Turnhout, 1991).

Peter Lombard, The Sentences. Edited and translated by Giulio Silano. Books I-IV (Pontifical Institution of Medieval Studies, Toronto, 2007).

Peter Lombard, Sententiae in IV libris distinctae: liber I et II. Vol I (Collegii S. Bonaventure Ad Claras Aquas, Grottaferrata, Rome, 1971).

William of Saint-Thierry, De la nature du corps et de l’âme. Edited and translated by Michel Lemoine (Société d’ Édition “Les Belles Lettres,” Paris, 1988).

William of Saint-Thierry, The Nature and Dignity of Love. Translated by Thomas X. Davis. (Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, MI, 1980).

William of Saint-Thierry, Nature et dignité de l’amour. Edited by Paul Verdeyen. Translated by Yves-Anselme Baudelet and Robert Thomas. Sources Chrétiennes 577 (Les Éditions du Cerf, Paris, 2015).

Notes

| ⇧1 | William of Saint-Thierry, De anima, in Three Treatises on Man: A Cistercian Anthropology, ed. and trans. Bernard McGinn (Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, 1977), Prologue, 1.105; William of Saint-Thierry, De la nature du corps et de l’âme, ed. and trans. Michel Lemoine, Sources Chrétiennes 577 (Société d’ Édition “Les Belles Lettres,” Paris, 1988), Prologue, 1.65. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Guibert of Nogent, A Monk’s Confession: The Memoirs of Guibert of Nogent, ed. and trans. Paul J. Archambault (Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA, 1996), 1.17, 58; Guibert of Nogent, De Vita Sua Sive Monodiarum Libri Tres, in Guibert de Nogent: histoire de sa vie (1053–1124), ed. Georges Bougin (A. Picard, Paris, 1907), 1.17, 64. |

| ⇧3 | William of Saint-Thierry, The Nature and Dignity of Love, trans. Thomas X. Davis (Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, MI, 1980), Prologue, 2.49; William of Saint-Thierry, Nature et dignité de l’amour, ed. Paul Verdeyen, trans. Yves-Anselme Baudelet and Robert Thomas (Les Éditions du Cerf, Paris, 2015), Prologue, 2.92–5. |

| ⇧4 | My translation; Latin text available in Jean Leclercq, “Virgile en enfer d’après un manuscrit d’Aulne,” Latomus 17 (1958) 731–6. |

| ⇧5 | Peter Lombard, The Sentences, ed. and trans. Giulio Silano, Book I (Pontifical Institution of Medieval Studies, Toronto, 2007), Distinction 3.9, 21; Peter Lombard, Sententiae in IV libris distinctae: liber I et II, Vol I (Collegii S. Bonaventure Ad Claras Aquas, Grottaferrata, Rome, 1971), Book I, DIII:1,9, 71. |

| ⇧6 | Hugh of St Victor, De arca noe morali, in Selected Spiritual Writings, trans. a Religious of C.S.M.V. (Faber and Faber, London, 1962), 3.10.109; Hugh of St Victor, De archa noe, ed. P. Sicard (Brepols, Turnhout, 2001), 3.11.72. |

| ⇧7 | John of Salisbury, Metalogicon, ed. and trans. J.B. Hall (Brepols, Turnhout, 2013), 4.13, 301–2; John of Salisbury, Iohannes Saresberiensis: Metalogicon, ed. by J.B. Hall (Turnhout: Brepols, 1991), 4.13, 151–2. |

| ⇧8 | Bernardus Silvestris, Poetic Works, ed. and trans. Winthrop Wetherbee, Dumbarton Oaks 38 (Harvard UP, Cambridge MA, 2015), Megacosmos 3.32–5. |

| ⇧9 | Aelred of Rievaulx, Spiritual Friendship, in Writings on Body and Soul, ed. and trans. Bruce L. Venarde, Dumbarton Oaks 71 (Harvard UP, Cambridge MA, 2021), 1.7, 26–7. |

| ⇧10 | Isaac of Stella, Letter on the Soul, in Three Treatises on Man, 12.165; Isaac of Stella, Lettre Sur L’ Âme, Lettre Sur Le Canon De La Messe, ed. Elias Dietz and Caterina Tarlazzi, trans. Laurence Mellerin and Robert Favreau, Sources Chrétiennes 632 (Les éditions du Cerf, Paris, 2022), 20.183. |