Mike and Richard Fontaine

Those hoping to see the Roman world’s remaining wonders generally know where to look. Pompeii and the Colosseum are squarely on the beaten track, and so are other marvels scattered around Britain, Europe, and Turkey. More adventurous types might journey to Baalbek in Lebanon or Leptis Magna in Libya. Few, however, make it to Algeria. But we recently did, and there we saw some of the world’s greatest – and least visited – Roman ruins.

It was an exceptional visit, unlike any either of us had ever undertaken. This photo essay shares a few Classics-inflected impressions from a week on the road. Quite simply, the Algerian people are warm, the infrastructure superb, and after Pompeii and Ostia in Italy, the Roman sites at Djémila and Timgad (“the Pompeii of Africa”) are the best in the world. The seaside remains at Tipasa aren’t far behind.

Best of all, we had these places nearly to ourselves. Walking through the sprawling, preserved Roman cities in Algeria may well be a 21st-century traveler’s single best opportunity to imagine life in the Empire two thousand years ago.

It was a brothers’ trip. Mike visited as a Cornell University Latinist, Richard as a very informal French interpreter and Professor Mike’s plus one (though with a concurrent interest in the country’s politics). We weren’t sure what to expect. Almost no-one we know had traveled to Algeria, and guidebooks are virtually nonexistent (Lonely Planet, for instance, publishes travel guides to Antarctica and North Korea but has none for Algeria). Africa’s largest country – and its 45 million people – are a giant blank space in most people’s knowledge. For those reasons and more, we were keen to go.

For a Classicist, Algeria’s attractions are obvious. After Italy and maybe Spain, Algeria – known as Numidia in Classical antiquity – produced more Latin literature than any other region. Latin was spoken there for at least six centuries, and maybe even ten. St Augustine lived in Hippo and Apuleius came from M’Daourouch, while Fronto (who taught Marcus Aurelius), Lactantius, and Minucius Felix resided in Cirta (modern Constantine, a spectacular city of gorges and, yes, named for the Emperor). The Augustan writer Juba II ruled Mauretania from the coastal city of Caesarea (modern Cherchell), where Latin grammarian extraordinaire Priscian later grew up. Martianus Capella, Nonius Marcellus, and maybe even Suetonius were Algerians too. (By contrast, in antiquity France produced only two Latin authors – the historian Pompeius Trogus and, er, Ausonius – while England, Switzerland, Belgium, and Germany produced none at all.)

Algeria’s writers were Romanized Berbers, a group that remains in Algeria today. In ruins, place names, and much more, Algeria remains replete with remnants of Ancient Rome, though Latin as a subject of academic study appears virtually nonexistent there. In a land where Arabic, French, and Berber are the languages spoken now, we wished to hear what Algerians today think of their impressive Roman past.

Alas, that past is only one of many that lies just below the modern surface. After driving out the colonial French in a brutal war of independence in the 1950s and 1960s, Algeria sank into a civil war that raged throughout the 1990s. (The gripping 1966 film The Battle of Algiers is a superb introduction to the war for Algerian independence.) The anti-colonial fight is a constant presence in murals, monuments, literature, and conversation, while the “Black Decade” of the 90s hardly figures. The government’s overwhelming desire for stability helps explain some of the country’s idiosyncratic peculiarities.

The difficulty getting in as a traveler, for instance, is one. Tourist visas are hard to come by: Mike’s took four months to process and required repeated emails, phone calls, and two in-person visits to the New York consulate to obtain. The economy runs on cash, and mostly small bills: good luck closing your wallet. No credit cards, no ATMs for foreign withdrawals, and the official exchange rate is half what traders on the hardly-concealed black market offer. (Guys with bundles of cash, proficient with their phones’ calculator apps, hang around public squares in downtown Algiers.) Even in five-star hotels, you can’t charge to the room – meals and all else have to be paid in cash each time. There’s virtually nothing in the way of tourist infrastructure, either. There’s excellent travel infrastructure – wonderful highways, good restaurants, WiFi everywhere, and upscale lodging – but for tourists specifically, nada.

Our lack of advance knowledge led us to channel the historian Timaeus of Tauromenium, as skewered in a famous sentence of Polybius (12.3, here):

τὸν δὲ Τίμαιον εἴποι τις ἂν οὐ μόνον ἀνιστόρητον γεγονέναι περὶ τῶν κατὰ τὴν Λιβύην, ἀλλὰ καὶ παιδαριώδη καὶ τελέως ἀσυλλόγιστον καὶ ταῖς ἀρχαίαις φήμαις ἀκμὴν ἐνδεδεμένον, ἃς παρειλήφαμεν, ὡς ἀμμώδους πάσης καὶ ξηρᾶς καὶ ἀκάρπου καθυπαρχούσης τῆς Λιβύης.

One is inclined to say that Timaeus was not only unacquainted with Africa but that he was childish and entirely deficient in judgment, and was still fettered by the ancient report handed down to us that the whole of Africa is sandy, dry, and unproductive.

One or the other of us had visited all the other countries of North Africa. We knew that Algeria had once been the breadbasket of the Roman Empire, and that it was situated on the Mediterranean, but we anticipated a desert country, perhaps with occasional strips of green. We figured it would be dry, rocky or sandy, and maybe barren between the cities.

Not so. Much of Algeria resembles the south of France far more than it does Cairo or the Sahara.

The landscapes feature rolling hills and flat expanses of gorgeous green crops. The red soil resembles Alabama dirt and some of the agricultural fields look like rural Texas. Gentle salt lakes, fields of wild red poppies, and lush vegetation are everywhere. Go far enough south and you’ll hit rocky desert, and eventually sand. But Algeria’s green areas are vast, allegedly larger than Germany, England, or Spain. The geography and climate are Mediterranean, through and through. (The temperature hovered around 72 degrees Fahrenheit, or 23 Celsius, the whole week we were there.)

It made visiting the Roman sites a delight in spring weather. The three grandest are Djémila, Timgad, and Tipasa, and in that order. All three are huge and sprawling, exceptionally well preserved, and each features stunning little museums crammed with floor-to-ceiling mosaics and sculpture.

Since the sites are not close to each other, we had a private driver shuttle us among them. We used Constantine as a base for exploring Djémila and Timgad, and Algiers for visiting Tipasa. Each was spectacular.

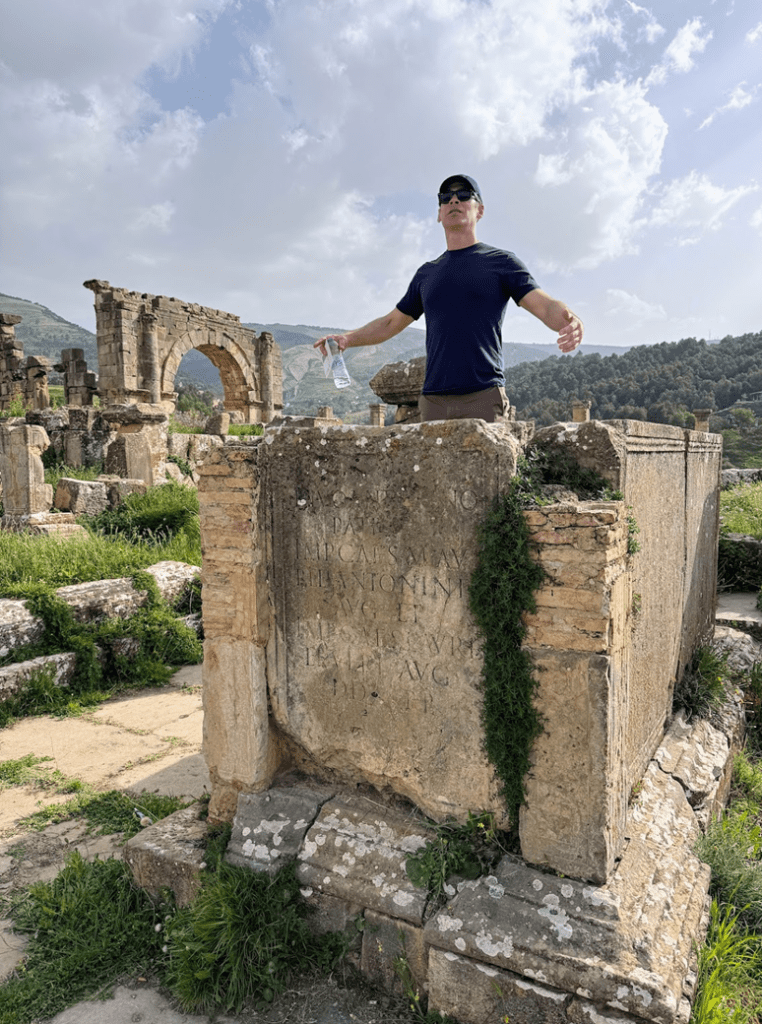

Djemila

Including stops, the drive from Algiers to Djémila took five hours. It was worth it. The city was founded under Nerva and prospered for four centuries before it was abandoned, becoming a ghost town like Ostia in Italy. The ruins rival those at Pompeii, but the site couldn’t be more different. It’s perched on a gorgeous peak flanked by two rivers and surrounded by stunning, gentle verdant hills.

The ruins are in an incredible state of preservation. The forum, baths, theater, and temple are all immediately recognizable, and the market (macellum) was in exceptional condition; even the stall tables and measuring stone were intact.

The theater, too, is in excellent shape. Its stage tempted one of us (Professor Mike) to deliver an impromptu oration in Latin, attracting attention from the tiny handful of sightseers wandering around.

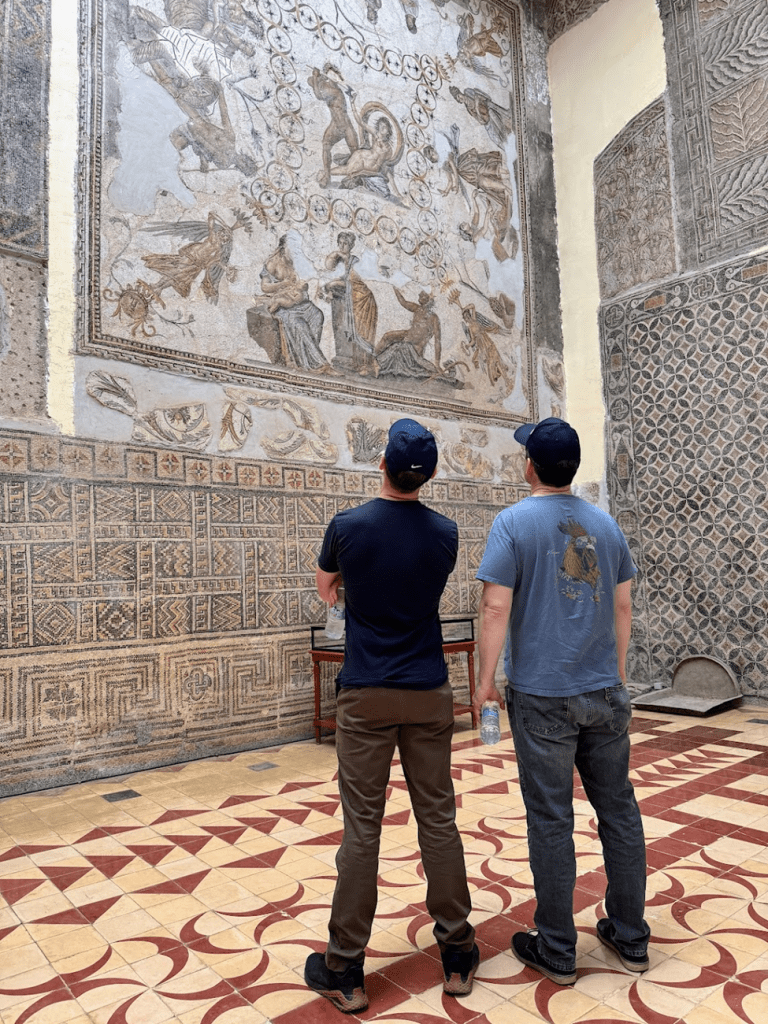

The museum on site is similarly stunning. It houses floor-to-ceiling mosaics taken from wealthy homes that clearly required enormous wealth and effort to create.

One unusual sight was a (non-working) Roman jet fountain, possibly the last in existence. It’s built downhill from the baths – and hence is gravity-powered – and looks like the conical meta sudans that once stood next to the Colosseum in Rome.

Despite all this, the site was virtually empty. During the four hours we spent walking around, no more than fifteen other people passed through (including a jogger getting some magnificent daily steps in). All were Algerian, or French people of Algerian descent.

Timgad

The drive to “the Pompeii of Africa” (as the locals call it) took another four or five hours but was again well worth it. And on the way, we stopped to see the Royal Mausoleum of Numidia.

The expansive city itself is in amazing shape, and once more we had the whole place virtually to ourselves. Trajan founded the place as a military colony in AD 100, just a couple years after Djémila. It sits just north of the Aurès mountains and was meant to ensure the non-Romans living out in the hills stayed put. The city lies on flat land and its grid pattern remains remarkably clear.

Although the setting and scenery are nothing like Djémila’s, the mosaics, theater, market, and forum were equally breathtaking, and the main arch gate was spectacular.

The market was so well-preserved that it inspired one of us (again, Professor Mike) to take up position behind a stall table and hawk wares in spoken Latin.

Even the loo was easy to spot.

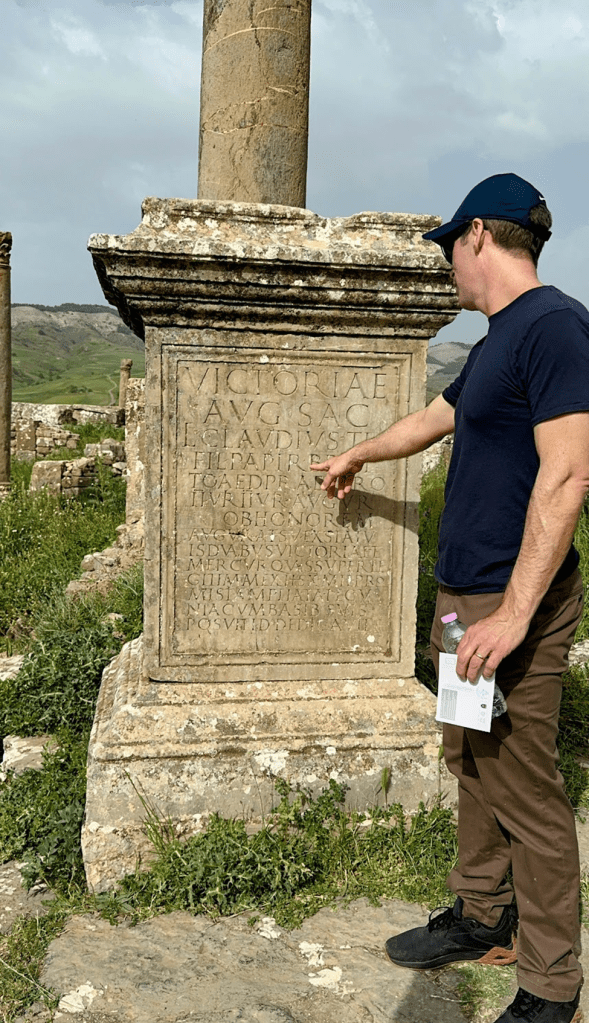

A delightful bonus was our warm and wonderful guide, Hamid, AKA Guide Adel. Hamid speaks perfect English and has been leading tours there for twenty years. He not only has a deep and detailed knowledge of everything about the site, but he’s also been learning Latin from a French textbook and YouTube videos. He was especially keen to watch Mike read some of the many Latin inscriptions that litter the site. (Richard took photos and looked at the flowers while these two geeked out over obscure abbreviations on pillars and burial stele.)

Tipasa

A 90-minute drive from Algiers, Tipasa was built by Claudius as another retirement community for Roman soldiers, and on top of an earlier Punic site. The very extensive ruins perch spectacularly above the Mediterranean Sea, and we strolled through the ancient town as waves crashed against the shoreline below.

The town layout and buildings are easily recognizable, although unlike Timgad and Djémila, none are especially well preserved. The amphitheater is one of the best.

What gives the site its charm are the endless trees that fill the area, so many that the site is more like a huge public park than a slog through ruined buildings.

Unlike the first two sites, too, this one was filled with local tourists and others out for a day in the sun. We met a Harley Davidson biker club that brought together riders from Algeria, Jordan, Kuwait, and Syria, and we quickly made friends despite the language barrier.

On the way to Tipasa is the charming seaside village of Cherchell. This was the royal residence of Juba II, and its impressive little museum is packed with statuary, mosaics, and inscriptions.

The museum director – an underwater archeologist – struck up a chat when he saw Mike reading one of the Latin funerary inscriptions. This man turned out to be the only person in Algeria we met who had studied Latin in a university setting. He had taken two years of it (in French) at Algiers’ University 2 Bouzareah, which suggests that despite all other signs to the contrary, the “dead” language lives on.

Still, people did not know Latin literature first-hand but some certainly knew their history. The names of Masinissa, Syphax, Juba I, and Juba II were said with pride, and just outside the Tipasa ruins we spotted a “Restaurant Syphax”.

On our way back to Algiers, we stopped off to see the Mausoleum of King Juba II and Cleopatra Selene II, daughter of the famous Cleopatra and Mark Antony (here). Not only was it huge and inspiring – sitting as it does on top of a hill swept by invigorating fresh air and breezes – it overlooks a stunning landscape in every direction (seaside in front, gorgeous farms behind). Kids were climbing all over it, so we did, too.

Constantine

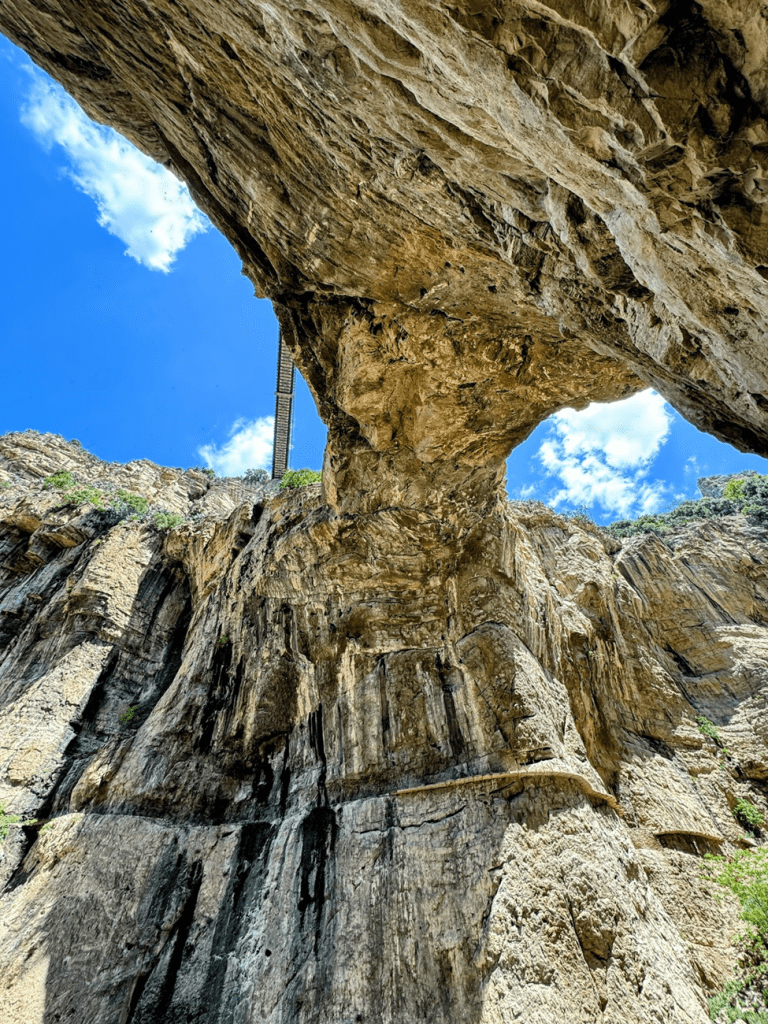

An unexpected highlight of our trip was the city of Constantine. That’s ancient Cirta – the last redoubt of Syphax, the home of Fronto, and much more. The city sits high on top of a huge rock gorge.

Once again we had a fantastic tour guide, Imen Guerrach. After meeting us at the hotel she took us to explore the city’s enormous mosque, which looks a bit like the Taj Mahal from the front and boasts a beautiful interior.

After that, we drove down and hiked into the gorge to look up at the city’s three natural bridges.

We then hiked over the old Roman aqueduct in midair.

The small local antiquities museum houses tons of coins, inscriptions, and funerary stelae. Some were in Latin, others in Punic.

And, of course, spectacular mosaics.

We ended the day at a city park back up top, where we looked out over endless vistas that could easily be mistaken for central Italy.

Algiers

Of Algiers itself (Classical Icosium), there’s little to say. The Casbah (medieval quarter) was interesting and the Botanical Gardens outstanding.

Otherwise, though, it’s a modern waterfront city with some impressive but unexceptional museums and colonial architecture. Classics-minded visitors to Algeria would do well to use it as a base for exploration elsewhere.

Conclusion

Our trip to Algeria was awesome. We fell in love with the country and the people and hope to return someday – or better yet, to open up some contacts and create some cultural exchanges.

The country has all the modern conveniences and infrastructure you get in any other first-world country. But the prices are literally pennies on the dollar. Lunch for three in Timgad village was $5.00. A five-star dinner for two in Algiers, including a bottle of Algerian wine and served by men in tuxedos, was $22.00. And so on. There’s no McDonald’s, or Starbucks, and Coke Zero exists but, as Juvenal or Taleb might say, it’s a rara avis in terris nigroque simillima cygno (“a rare bird on planet earth, and pretty much a black swan”). Enjoy the country’s sui generis character – before it changes.

Was it dangerous? Not in our experience. Algeria has that reputation, but we did not feel unsafe at any time. Indeed, Algiers in our hometown of New Orleans is surely more dangerous than Algiers, Algeria. Of course, it depends on where you go, and when, and the US State Department’s travel advisory parses things well. But the people could not have been friendlier, and they certainly seem to like Americans (which is a nice change). We fist-bumped and posed for selfies with locals everywhere.

It would have been impossible to plan this trip on our own, so we had – and highly recommend – an excellent Algerian travel company, Fancy Yellow, plan and coordinate our itinerary. They took care of every detail, from help with visas to booking the hotels and internal flight to the private drivers, and they lined up knowledgeable and informed tour guides for every site and sight we saw.

Finally, Algeria is in a state of transition. While we focused little on its politics and policies, they are complicated and tend toward isolation. The language is also in flux. Ten years ago we’d have had to speak far more French, and in ten years from now English may be all you’ll need to get around. On this trip we used a mix.

But if you get the chance to go, don’t wait. Because Algeria is amazing, and it was a privilege to see it.

Mike Fontaine teaches Latin at Cornell University. His new translation of Ovid’s Remedies for Love is in the same meter as the original, but disguised as prose so people will read it. It might help train your students’ ears.

Richard Fontaine is CEO of the Center for a New American Security. He has worked at the US Department of State, on the National Security Council, and as a foreign policy adviser to US Senator John McCain.

(All photographs above were taken by the authors and are free for anyone to reproduce.)

Further Reading

The Roman historian Sallust gives a fascinating account of Numidia’s (legendary?) origins early in Jugurtha’s War (Loeb translation accessible here), where he points out that “Numidia” means “land of the nomads”. Every Classics enthusiast should read it.

Barry Baldwin surveys Algerian and other Latin authors of the Maghreb in “Some pleasures of later Roman literature: The African contribution”, Acta Classica 32 (1989) 37–57 (accessible here), while for ancient daily life we recommend R. Bruce Hitchner (ed.), A Companion to North Africa in Antiquity (Wiley, Chichester / Hoboken, NJ, 2022). Duane Roller’s monograph The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene (Routledge, London, 2003) is an excellent introduction to two very important but forgotten figures of the Augustan Age.

For contemporary Algerian society, Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 film The Battle of Algiers is not just one of the greatest films of all time, it’s also a superb introduction to the 1954–62 Algerian War of Independence. Zohra Drif’s 2017 memoir (French original 2013), Inside the Battle of Algiers: Memoir of a Woman Freedom Fighter, offers an insider’s account of that battle (as a college student Drif planted a bomb in Algiers’ Milk Bar Café, killing three, and later became an influential politician).