Francis Young

For more than four centuries (between 1385 and 1795) a single vast polity dominated East-Central Europe, in the area between the Baltic and Black Seas. Although only formally known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569, Poland-Lithuania was a complex entity that took in not only present-day Poland and Lithuania but also present-day Belarus, much of Ukraine, and at times parts of present-day Latvia, Estonia, and European Russia. The dismemberment of this polity by the Russian, Austrian and Prussian empires at the end of the 18th century not only wiped it from the map but also seemingly wiped Europe’s collective memory of this extraordinary state and its cultural achievements.

The terrible suffering endured by this region in the Second World War and under Communism now overshadows Poland-Lithuania’s long history as a flourishing realm whose Classical learning, among other things, was admired throughout Europe. The nobility of Poland-Lithuania, eager to situate themselves within the Classical world, famously identified themselves as the ‘Sarmatians’ of the ancients, and accordingly shaved their heads, grew enormous moustaches, and wore Ottoman-inspired robes.

But Polish-Lithuanian interest in the ancient world was more than cosplay. Poland-Lithuania was a state without a common language, and large portions of the population spoke only in their respective languages: Polish, Ruthenian, Lithuanian, German, and Yiddish. It was not until the 18th century that Polish established itself as an elite lingua franca throughout the whole region. Up to that point, Latin was often more widely understood by the clergy and university-educated nobility than any other language, and the universities of Kraków and Vilnius excelled as centres of Latin poetics.

Poland-Lithuania’s literature was Latin, and the Jesuit Professor of Poetry at Vilnius, Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski (1595–1640), known as Sarbievius, achieved worldwide fame for his Horatian odes. One reason for the popularity of Latin in Poland-Lithuania was a belief among the Lithuanian nobility that the Lithuanian language (at that time spoken only by the largely pagan peasantry) was a degenerate form of Latin, planted in the Baltic by Roman exiles. Lithuanians argued that Latin should be the official language of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, not just as a convenient lingua franca but because Latin actually was the ancient language of Lithuania.

We know now that these advocates of Latin had unwittingly stumbled on the archaic Indo-European characteristics of the Lithuanian language, which lend it a superficial resemblance to inflected Latin. But the idea of Latin as a national language of Poland-Lithuania began to take root; and the nobility of the Commonwealth, as well as identifying themselves as Sarmatians, began to see themselves as a patrician class of citizens within a republic mirroring republican Rome. For although the Commonwealth had a king, he was elected by the nobility, with a “free election” system established in 1573.

The king was mostly subject to the Sejm (parliament); indeed, the Polish word we translate as ‘commonwealth’ (Rzeczpospolita) really just means ‘republic’. A shared sense of Romanitas united the nobility of this complex and disparate realm, and one genre of Latin was prized above all: epic inspired by the poetry of Virgil.

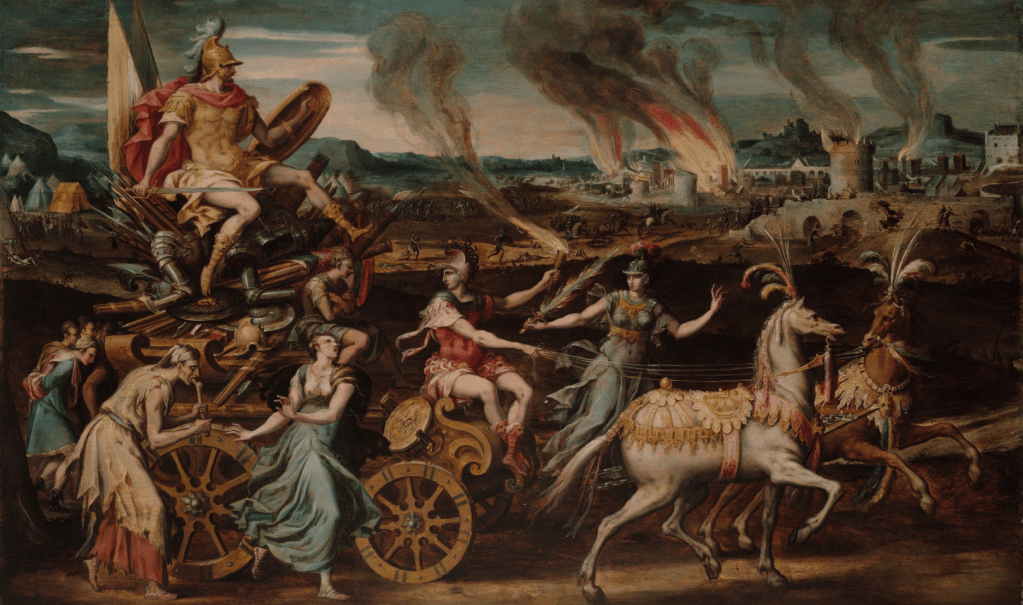

Just as Virgil’s Aeneid had conferred a new identity on Rome in the era of Augustus, so early modern Polish and Lithuanian authors sought to build an identity for their nation through epic poems. In 1516, a Polish poet at the University of Kraków, Joannes Vislicensis (we only know his Latinised name) wrote the epic Bellum Prutenum (‘The Prussian War’) about King Władysław II Jagiełło’s victory over the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. Just as the Aeneid had glorified the Julian dynasty, so Bellum Prutenum glorified the Jagiellonians descended from Jagiełło, the king who first ruled both Poland and Lithuania – and indeed claimed that his deeds excelled those of ancient heroes:

Felix hic tanti Iagello gloria belli,

Qui modo praecellit clarorum gesta parentum,

Ingenio celebres priscos fortes et in armis

Vincens martiacis cum tot feliciter actis.

Cui, tu Roma, tuos noli annumerare Camillos,

Marcellum. Fabios et Caesaris optima gesta,

Hectora, Troia, tuum, fortem, Larissa, et Achillem,

Hannibalemque tuum, Carthago superba, ferocem;

Et quos Persae, Arabes, Parthi Graique loquaces

Commemorant, retro huic cedant virtutis honore

Egregii et gestis proceres regesque potentes.

Fortunate was this Jagiełło in the glory of such a war, who now excels the deeds of his famous ancestors, the famous strong men of old, in his talent, and fortunately conquering in warlike arms with so many deeds. Do not reckon to him, o Rome, your Camillus, Marcellus, or Fabius, and Caesar’s excellent deeds; or your strong Hector, o Troy – and Larissa, your Achilles, or your fierce Hannibal, o proud Carthage; and those whom the Persians, Arabs, Parthians and talkative Greeks commemorate; let these foremost men and powerful kings yield to this one both in honour for their virtue and in their deeds.

Jagiełło’s descendants went on to rule not just Poland-Lithuania but also Bohemia (since 1471) as well as Hungary and Croatia (since 1490). But by the late 16th century, the triumphant Jagiellonian dynasty faced a problem: it was running out of heirs. The Union of Lublin provided the solution in 1569: on the death of the last Jagiellonian, kings would be elected. Yet this new patrician republic soon came under attack from the expanding Grand Duchy of Muscovy (the future Russian Empire), and writers of epic acquired a new subject: the towering military achievements of the Lithuanian Radziwiłł family in the long-running Livonian War (1558–83), in which Muscovy, Poland-Lithuania and others fought for control of Livonia (present-day Latvia and Estonia).

The fact that the Radziwiłłs were the Commonwealth’s leading literary patrons no doubt ensured the centrality of their exploits to a new style of epic poetry celebrating recent military victories. One such poem was Franciszek Gradowski’s Hodoeporicon Moschicum (‘Muscovite Expedition’) of 1582, which recounted Krzysztof Radziwiłł’s daring raid into Muscovy in 1581 – which came within a hair’s breadth of capturing Ivan the Terrible himself. Ironically, the devastation of Polish-Lithuanian archives over subsequent centuries mean that Gradowski’s poem is now the principal historical source for what actually happened during Radziwiłł’s raid. However, no-one assumed the Virgilian mantle as seriously as Jan Radwan, the author of Radivilias (1592), an epic of 3,302 lines in four books about the exploits of Mikołaj ‘the Red’ Radziwiłł against the Muscovites – the most ambitious of all Polish-Lithuanian epics. In the light of modern Lithuania’s successive occupations by the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, Radivilias is a poem that still speaks to Lithuanians today.

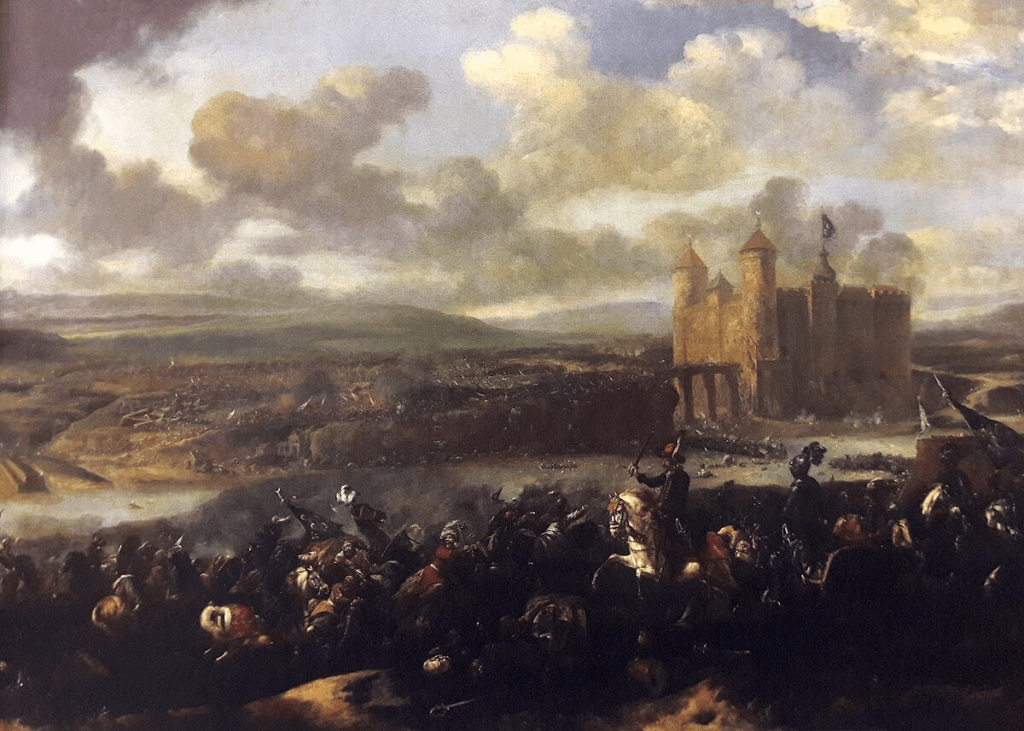

Poland-Lithuania’s embattled geographical location between the Russian, Swedish, Austrian and Ottoman empires did not make for a peaceful history, and epic became a way of celebrating the nation’s achievements against all its enemies. Where Gradowski and Radwan had celebrated victories against the Russians, Krzysztof Zawisza’s Carolomachia (1606) glorified Jan Karol Chodkiewicz’s victory over the Swedes. But in 1655 disaster struck; the Swedes and Russians simultaneously invaded and overwhelmed the Commonwealth, which lost a third of its population to massacres, emigration, famine and disease. The Commonwealth subsequently fell prey to the Ottomans, who tried to make Poland-Lithuania pay tribute as a vassal state.

Poland-Lithuania’s conflict with the Ottoman Empire was the background to the last great Polish-Lithuanian Latin epic, James Bennett’s Virtus dexterae Domini (‘The Strength of the Lord’s Arm’), which was furiously composed in a matter of weeks after the Polish-Lithuanian victory over the Ottomans at the Battle of Khotyn (1673). Khotyn saw the rise of a new Polish leader, Jan Sobieski, who was to become both King of Poland and the most famous warrior in Christendom when he broke the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683 with the largest cavalry charge in history, leading his terrifying ‘winged hussars’ down a steep slope to smash the Sultan’s janissaries and end Ottoman expansion forever.

For the Scottish émigré author James Bennett, these glories lay in the future. Yet Sobieski’s victory at Khotyn was impressive enough, and Bennett fashioned an extraordinary baroque poem that introduced a new nationalistic fervour to the epic tradition. Here, for example, Bennett personified the Lithuanian nation as Mars the god of war, whom he has address the Turks directly:

Auxit opus belli, Mavors Litvanus: amore

Qui Patriae succensus, agi cum Thraca minaci

Advertit rabie, lucrisque inhiare nefandis:

Arma manu gladiosque rapit, plenusque furore

Ardenti, talem fundit de pectore vocem:

‘Et potes insultum moliri Turcica pestis

Sarmatiae, patriamque tuis impune tributis

Ludere, vindictam penitus trepidare nec ullam

Foederibus ruptis? Testor per fata, per omnem

Astrorum Nemesim; non haec incendia belli

Extinguam; donec vestrum libabo cruorem.’

Vix ea: cum subito fertur Litvana potestas

Intrepidique Duces animis et viribus aequis

Educunt aciem …

…

Fluctuat omnis ager, late splendentia pulsu

Scuta sonant; planis crebrescit ahenea campis

Sylva; ruunt cupido mentes ad proelia sensu:

Et licet immitis Boreas obstaret acerbis

Auribus, et pluvio premeret vesanior Euro

Autumnus caelumque viros: tamen ardet in armis

Litvanus; secumque trahit Gediminia vota.

Lithuanian Mars increased the work of war; inflamed by love of his fatherland, when he realises that Thrace is acting with menacing madness, and longing for heinous profits, he seizes arms and swords with his hand, and filled with ardent fury he pours words such as these from his breast: ‘Turkish plague of Sarmatia, are you able to set in motion an attack, and to mock the fatherland with impunity with your tributes? Do you dare almost any vengeance with broken oaths? I swear by the fates, by every Nemesis of the stars, I will not put out the fires of this war until I pour out your blood in libation.’

He had scarcely spoken, when suddenly the Lithuanian power comes forth, and the intrepid leaders lead out the column with calm spirits and strength … Every field shakes; the resplendent shields sound widely with a strike; it fills the bronze woods with noise in the wide plains. Souls rush into battle with eager passion. And the north wind is allowed to stand against them with cruel and bitter gusts; and autumn presses the men and the heavens with a more frenzied, rainy east wind. The Lithuanian, however, burns in arms, and bears with him the vows of Gediminas.

James Bennett’s Virtus dexterae Domini turned out to be the swansong of the Polish-Lithuanian epic tradition, at least in Latin. The 18th century saw the final triumph of Polish as the language of vernacular literature, although the earlier epic tradition continued to echo in new vernacular epics such as Ignacy Krasicki’s Wojna Chocimska (‘The Khotyn War’), published in 1780 and Adam Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz (1834). Indeed, so powerful was the influence of Virgilian epic that Kristijonas Donelaitis wrote the first extended poem in the Lithuanian language, Metai (‘The Seasons’, 1765–75) in dactylic hexameters. Modern Lithuanian literature was thus born in the long shadow cast by Poland-Lithuania’s Latin epic tradition – a literature that simultaneously built up a national narrative of military victories and patrician Romanitas, yet made it possible for people of a variety of nationalities to feel part of a multi-ethnic commonwealth.

It can be difficult for the nations that later emerged on the former territory of the Commonwealth to reckon with their Latin literary heritage. Since the 19th century, these nations have tended to privilege the literary heritage of their national vernaculars to the exclusion of an earlier Latin literature seen as irrelevant – but that seems to be changing. Interest in the shared culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth is growing in Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine, in part out of a shared sense of solidarity in the face of contemporary Russian aggression.

The importance of the Latin language as a unifying mode of elite communication and shared cultural reference in early modern Poland-Lithuania was not unique – Latin played a similar role in early modern Hungary, for example – but the Lithuanians’ belief they were a Latin people may have been unique among the peoples of Eastern and Northern Europe, and in all probability prolonged the dominance of Latin literature in the Commonwealth.

Francis Young is the editor and translator of Poetry and Nation-Building in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: Three Early Modern Latin Epics, published by Arc Humanities Press in June 2024.