Carole Raddato

Tivoli (Roman Tibur), a picturesque town located approximately twenty miles from Rome, is renowned for its breathtaking hilly landscapes and elegant villas. This peaceful haven has always been a welcome escape from the hustle and bustle of the Eternal City, with its idyllic position along the Aniene River, crisp mountain air, and rejuvenating thermal waters. In ancient times, Tivoli was a popular retreat for the Roman elite, who built their country villas there. Later, during the Renaissance, Tivoli became the site of opulent residential estates with lavish gardens. Emperor Hadrian (ruled 117–38), known for his love for architecture and engineering, made a deliberate choice to construct his expansive Villa in Tivoli in the valley below the Tiburtine Hills.

The Site and its Setting

Laid out between AD 118 and 134 on top of a pre-existing Republican villa, Hadrian’s Villa is unrivalled in scale and architectural originality among all Roman villas. The complex, generously spanning an area of about 120 hectares (almost twice the size of Pompeii), featured 30 major buildings, including palaces, baths, libraries, theatres, extensive gardens and fountains, and multiple dining suites, all decorated with the most valuable materials and filled with art masterpieces.

The overall plan was complex and unusual, featuring a unique circular design, curvilinear architecture, clever use of convex and concave curves, and domes and vaults made of brick-faced concrete. Designed for both business and pleasure, the Villa also contained many rooms that could accommodate large gatherings for the Empire’s elite. A large court lived there permanently, and many visitors and bureaucrats were entertained and temporarily housed on site. The servants had their quarters in hidden rooms and used service tunnels to transport goods from one area to another, well out of sight of the Emperor. As a result, the vast residential complex was almost always bustling with people.

Whenever Hadrian returned to Italy from his endless journeyings across the Empire, he preferred to stay at his Villa in Tibur. Building work on the Villa started in AD 118, immediately upon the Emperor’s return to Rome after his accession, and continued intensely until his return from his first major journey in 125. Work continued between 128 and 134, while Hadrian was away on his second journey, leaving him six years at most to enjoy one of the largest estates ever built on earth.

Hadrian was passionately interested in architecture, commissioning more buildings in Rome and the cities across the Empire than any other emperor. He actively rehabilitated, repaired, or built new buildings, infrastructures, and votive or religious monuments. “In almost all cities, he had at least something built.” These are the words Hadrian’s biographer used in the 4th-century AD Historia Augusta[1] to describe the extent of the Emperor’s construction projects (Hadr. 19.2). To accomplish these works, Hadrian travelled with a team of “builders, stonemasons, architects and every kind of specialists for constructing walls or decorating buildings” (Pseudo-Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus (Summary of the Caesars) 14.5).

Hadrian was also the Emperor with the greatest admiration for Greece and Greek art and culture, to the point of earning the nickname Graeculus (the “little Greek”) at an early age (HA, Hadr. 1.5). Elected archon in Athens in 112, he showed munificence towards his favourite city, visiting it three times as emperor. He donated a library to Athens, as well as an aqueduct and pantheon, and restored the Temple of Olympian Zeus. It is reasonable to suspect that Hadrian was personally involved in the building projects, commissioning the construction of several structures that reflected his travels across the vast territories of the Roman Empire.

“[Hadrian] fashioned his villa at Tibur marvellously, and he actually gave to parts of it names of provinces and places most famous, calling them, for instance, Lyceum, Academia, the Prytaneum, Canopus, Poecile and [Vale of] Tempe. And, in order to omit nothing, he even made a Hades.” (HA, Hadr. 26.5)

Established Themes

A passage in the Historia Augusta, the only description of the Villa that survives in Roman literature, reports that Hadrian named some of the buildings in his Villa after celebrated places and monuments he had seen on his travels. Six are Greek, and one is Egyptian. The Lyceum, the Academy, and the Poecile (i.e.m the Stoa Poikile) reference Athens’s famous schools of philosophy.[2] The ornamental canal called the Canopus refers to the two-mile-long canal connecting the eponymous Egyptian town with the nearby Alexandria. Finally, the Vale of Tempe recalls the famous valley of northern Thessaly, associated with Apollo and Artemis. Of the seven names in the Historia Augusta, only the Prytaneum (the Town Hall of a Greek city state), which could have been a banquet/reception hall, has not been identified.

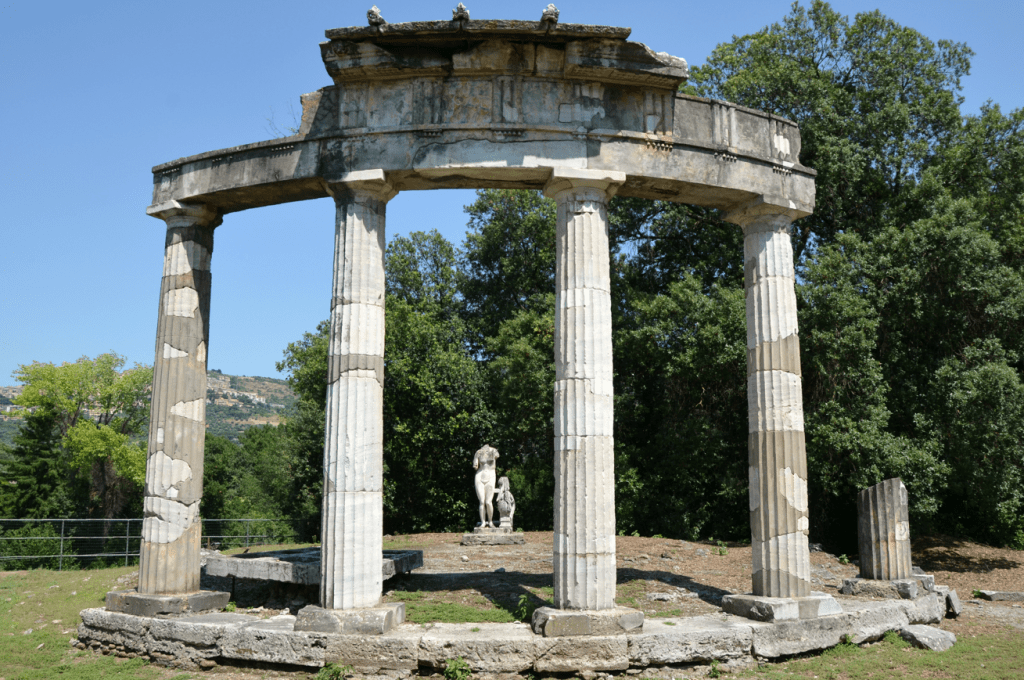

These structures were not exact replicas but stylised representations. However, one of the buildings in the Villa has a striking resemblance to a known prototype, the circular temple dedicated to the Venus of Cnidus. This temple, which featured a Doric tholos design, was situated on the island of Cnidus, overlooking the sea. Praxiteles’ original statue of Aphrodite was presumably housed inside the temple.

Hadrian’s commitment to Greek culture and philosophy, which took place against the background of a more general movement in Greek intellectual life, the Second Sophistic, certainly influenced his taste in art and architecture. The Villa, in addition to its architecture, is renowned for its extensive decorative program and large art collection. Hadrian’s Villa was filled with sculptures that incorporated the finest aspects of Greece’s architectural and cultural heritage, as well as Egyptian and Roman artistic traditions. Hadrian had a genuine interest in the provinces of Greece, Egypt, and Asia Minor, in particular: he intended for the Villa to reflect his extensive travels and personal passion for architecture, evoking architectural forms from all parts of the world. This syncretic blending was an important aspect of Hadrianic cultural policy and aesthetic vision.

The architect of the Villa is unknown, but it is believed that Hadrian played a personal role in its design.[3] The result was a magnificent creation featuring imaginative and unusual forms without strict axial symmetry and a varied and extensive collection of sculptures. The Villa served as a testament to Hadrian’s intellect and spirit and a reminder of his travels (HA, Hadr. 26.5). Essentially, it was a microcosm of his empire: the emperor could sit at the symbolic centre of the Roman world here, conducting state affairs in certain areas and pursuing intellectual interests in others.

Sculptures and Decoration

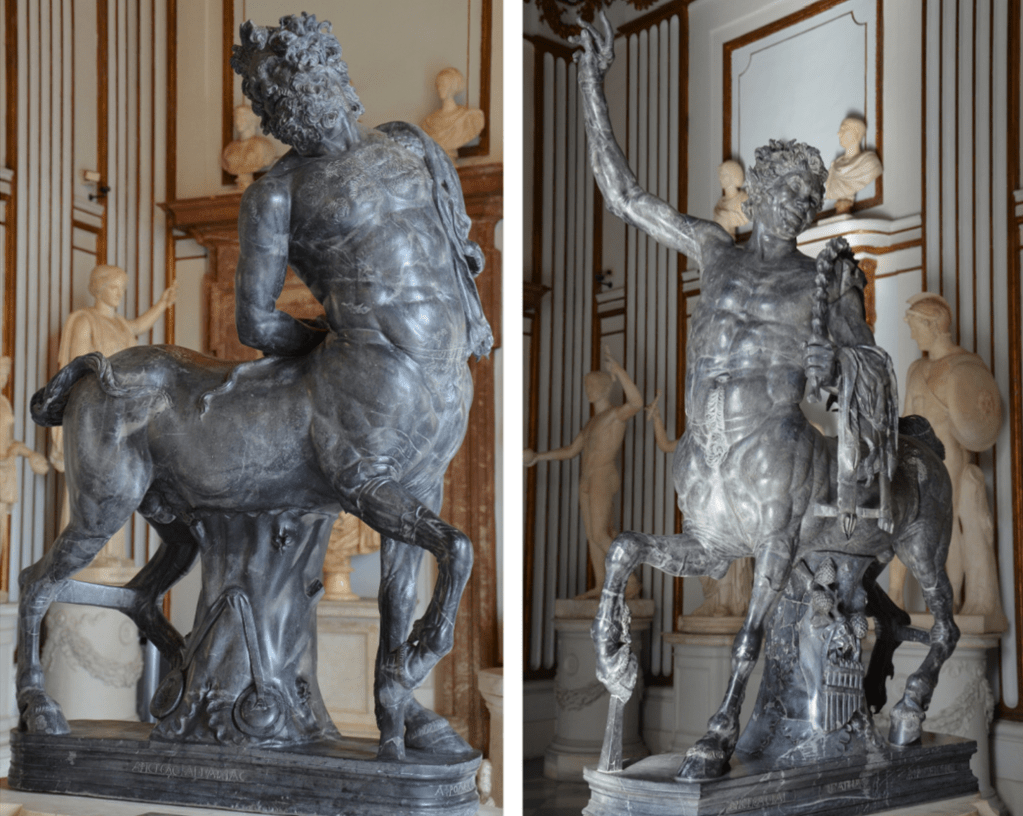

Over the centuries, no fewer than 400 statues, reliefs, mosaics, and architectural ornaments have been found in the Villa. Most of the more valuable items were taken from the Villa, especially during the 17th and 18th centuries, and are now dispersed across various museums in Europe and America. Some of the most famous statues are conserved in the Antiquarium of the Canopus at Hadrian’s Villa, but also in Rome in the Capitoline Museums (the famous Furietti Centaurs and the Fauno Rosso) and the Vatican Museums (the statue of Antinous-Osiris and all the other Egyptian-style sculptures from the so-called Antinoeion, the memorial monument dedicated to Antinous). These statues were found throughout the Villa complex; they adorned the Villa’s extensive gardens and courtyards and depicted gods, goddesses, and mythological figures. Dionysian, maritime, and hunting themes are present together with images of cupids and animals.

A recent study conducted on the sculptures from Hadrian’s Villa has revealed the origins of the marble used.[4] The study found that a significant portion of the marbles tested were sourced from Asia Minor, specifically from Göktepe near Aphrodisias in modern-day Turkey. The Göktepe quarries, discovered in 2006, provided high-quality marble and produced white and black statuary marble, as well as grey varieties, ultimately tied with the sculptors of the famous School of Aphrodisias. In fact, the two Furietti Centaurs, both signed by the Aphrodisian sculptors Aristeas and Pappias, were identified as black Göktepe marbles, while the Fauno Rosso proved to be red marble from the Iasos quarries in Caria. The Furietti Centaurs, a pair of dark grey life-size statues, are generally believed to be copies of a late 2nd cent. BC bronze Hellenistic original.

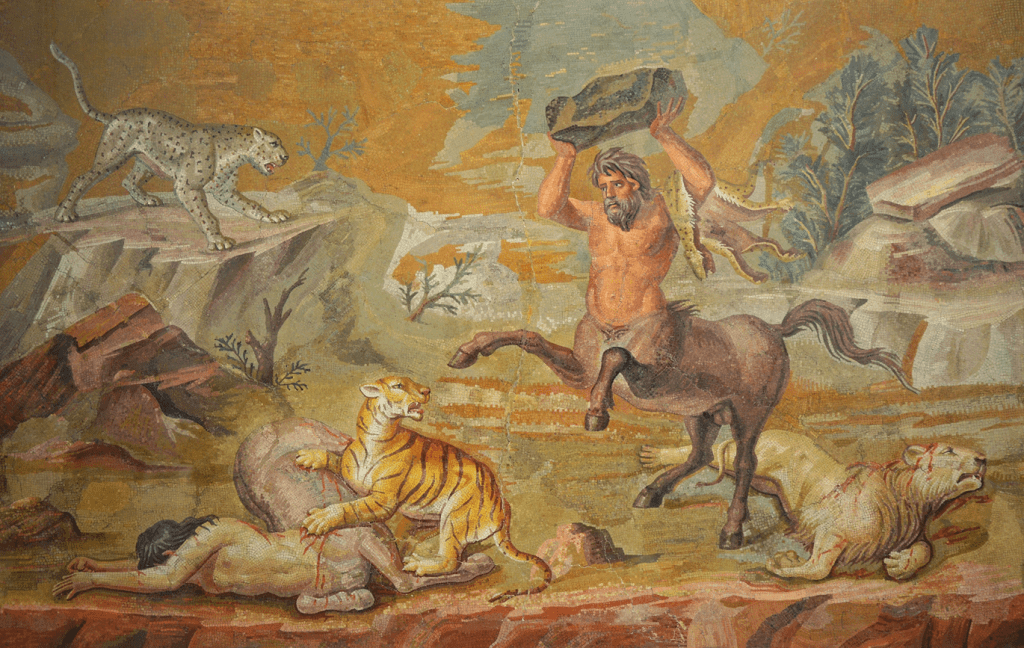

Mosaics were present throughout the Villa. Fine black and white mosaics covered the floors of the less prominent areas, such as sleeping accommodations for lower-ranking guests, while more elaborate and colourful mosaics adorned spaces frequented by the emperor. One of the most well-known mosaics from Hadrian’s Villa is the Capitoline Doves. It depicts four doves drinking from an ornate bowl and is a copy of a work by the Hellenistic artist Sosus of Pergamon. Sosus was the most celebrated mosaicist of antiquity, known for his “upswept floor” mosaics made with tiny tesserae (opus vermiculatum).[5] Another famous mosaic in Berlin shows a battle between centaurs and felines in a rocky landscape. Additionally, a series of heavily restored panels in the Vatican depict bucolic scenes with animals and theatrical masks. Most mosaics still in situ are black-and-white with geometric and floral designs. The most beautiful ones are from the Hospitalia, a two-story building with guest rooms.

Pavements in opus sectile (marble floor inlay) were a common feature in many parts of the Villa. These floorings were often designed in geometric shapes such as squares, circles, triangles, and lozenges and were made of precious and multi-coloured marble. They covered the most prestigious parts of the Villa, accompanied by designs in stucco work; the walls and ceilings were carefully plastered and painted with frescoes that featured geometric or naturalistic motifs or decorated with elaborate floral patterns in stucco work. Unfortunately, very little has survived, as the ceilings of most buildings have collapsed. None the less, there are noteworthy pieces in the Large Baths and, to a lesser degree, in the so-called Imperial Triclinium. No figural wall paintings have survived at the Villa.

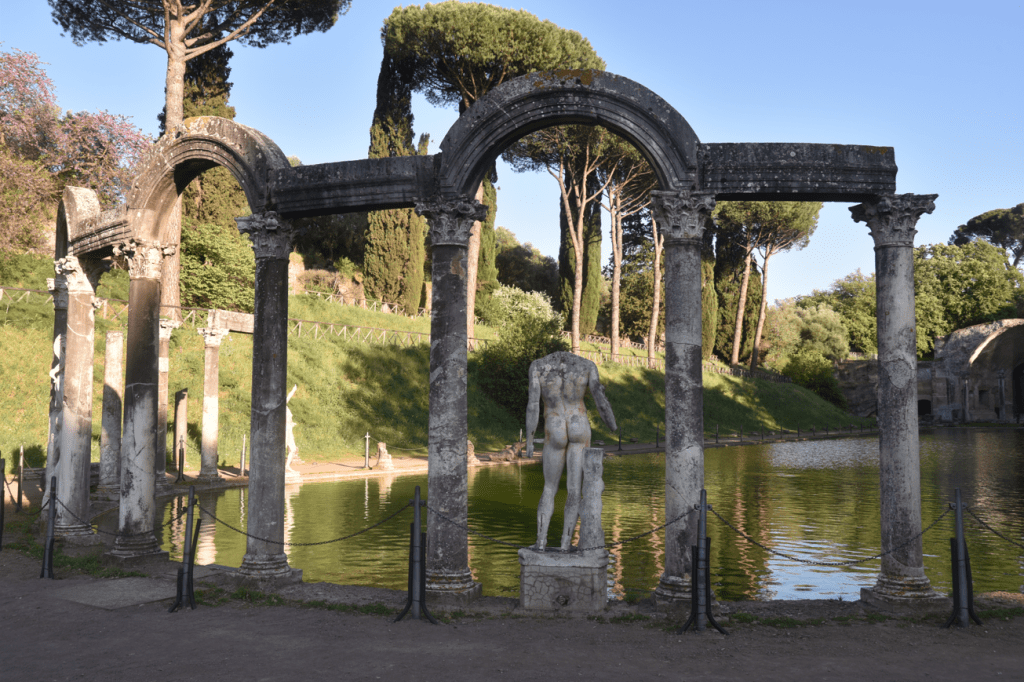

Greece and Egypt

Hadrian was particularly interested in highlighting the aesthetics of Greek art. He imported some of the most iconic images from Greece’s ancient heritage and brought together elements drawn from Greek architecture to his Villa in Tivoli. But Egyptian themes were also prominent, for Egypt was to play a major role in Hadrian’s life story. The artistic spirit of the Villa is best seen at the famed Canopus-Serapeum, a long pool of water reminiscent of the famous Egyptian city of Canopus and its canal that led to Alexandria. The main feature of the Canopus was the pool itself, 129 metres long and 19 metres wide, with statues arranged around the edges and inside the pool. At the southern end of the pool was a monumental, open, half-domed artificial grotto/dining room (the so-called Serapeum), where the Emperor and his guests would dine while enjoying the beautiful view of the Canopus to the sound of cascading water from the Nymphaeum behind.

The Canopus was adorned with marble statues that were larger than life. These were replicas of Classical Greek art and Egyptian-inspired statues. Among them were wounded Amazon copies, two Greek nude male statues interpreted as Hermes and Ares, a statue of Athena (of the Ince Blundell type) and four Caryatids flanked by Silenus figures supporting an entablature. The Caryatids are replicas of the Korai found in the Erechtheion of the Acropolis of Athens, characterised by belted peplos and elaborate hairstyles. On the other hand, the two Silenus statues resemble the sculptural decoration of the scaenae frons (stage building) of the Theatre of Dionysus on the south side of the Acropolis, initiated by Hadrian, who was honoured in Athens as Neos Dionysos (New Dionysus) and served twice (in AD 125 and 132) as the agōnothetēs (an official overseeing the dramatic competitions) of the Dionysia festival.

In addition to these sculptures, all discovered in their original places, the Canopus preserved reclining figures of the Nile and the Tiber, recognisable by the presence of the sphinx and she-wolf with twins, and a water-spouting crocodile carved from cipollino marble from the Greek quarries of Euboea (which colour was used to imitate the colour of crocodile skin). A Hellenistic sculpture group depicting Scylla, the monstrous sea goddess from the Odyssey who devoured sailors passing through the Strait of Messina, was placed on a rocky base on the east side of the pool.

The Piazza d’Oro, one of the most luxurious complexes at the Villa, richly decorated with floor and walls in opus sectile and friezes of hunting themes, had a similar plan to the Library of Hadrian in Athens. Situated on the northern edge of the Villa, Piazza d’Oro was a vast building with a large central garden flanked by flower beds and water basins, surrounded by a grand portico. On the south side of the Piazza, there was a series of rooms, including a cenatio (dining room), perhaps also hosting a library.

While Pausanias was particularly impressed by the “hundred pillars of Phrygian marble” of Hadrian’s library at Athens, Piazza d’Oro contained an impressive series of green Egyptian granite and pale cipollini marble columns. The impressive Vestibule of Piazza d’Oro – a vaulted structure unprecedented in earlier architecture – is a clear illustration of the kind of pumpkin dome for which Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan’s architect, had criticised Hadrian (Cassius Dio, Roman History 69.4). It is evident from the marble sculptures and architectural elements discovered that the emperor valued this space greatly. Among the artwork were also portraits of later emperors, such as Marcus Aurelius (ruled 161–80) and Caracalla (ruled 211–17), which attest to the continued use of the villa complex after the reign of Hadrian.

Elsewhere, the arrangement of sculptures in the rooms and gardens at the site was probably a deliberate choice made by Hadrian himself, as indicated by the pairing of specific statues with particular settings. For instance, a Doryphoros (“Spear Carrier”) statue of Polyclitus, one of the most famous Greek sculptures from Classical antiquity portraying a male athlete with idealised body proportions, was housed in the Small Baths. Similarly, the Heliocaminus Baths featured a Crouching Venus, a Hellenistic replica of the goddess surprised at her bath by Doidalses of Bithynia, while the Aphrodite of Cnidus by Praxiteles was positioned in the centre of the cella of the Doric round temple (tholos) of Venus.

A pair of marble herms, with heads traditionally identified as Tragedy and Comedy, was found near the entrance of the Greek Theatre. Additionally, larger-than-life marble theatrical masks decorated the scaenae frons (stage-building) of the Villa’s Odeon (a small theatre that could accommodate around 1,200 people) together with eight marble statues of seated Muses. The Muse group was created at the end of Hadrian’s reign by Roman workshops reproducing Greek models from the 2nd century BC. Ercole Ferrata, an Italian sculptor from 1610–86, heavily restored the Muses, giving them new attributes in accordance with their identification at the time. Only Terpsichore, the patron Muse of lyric poetry and dancing, was correctly identified. They are displayed with their Baroque-era names in the Prado Museum in Madrid.

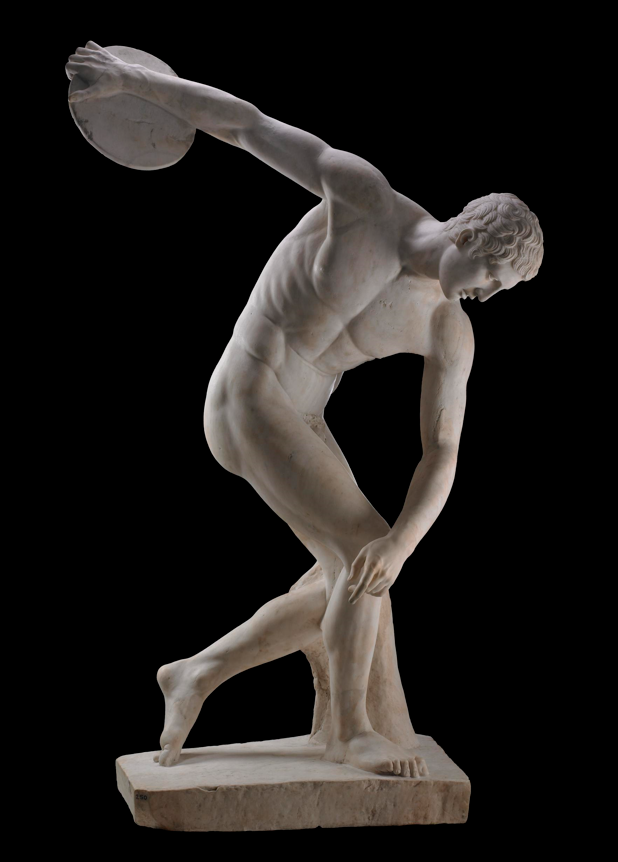

The Villa contained other Roman copies of masterworks of Classical Greece, such as Myron’s popular Discobolus (Discus Thrower), the Hermes Sandal Binder from the School of Lysippus and the Discophoros (Discus-Bearer), assigned to the sculptor Naucydes.[6]

During excavations in a marshy area around a small lake called Pantanello, Scottish painter and excavator Gavin Hamilton discovered a significant number of sculptures, fragments of vases, and various animal representations (such as a stag, ram, and peacock). He also found elegant ornaments, including a colossal head of Hercules, two Hadrian busts, and four Antinous portraits. Additionally, a marble head of a companion of Odysseus, part of a group depicting Odysseus with his twelve companions blinding the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, was found. This head was a copy of a famous Hellenistic work.

Hadrian mixed his prized Greek copies with various Egyptian-inspired sculptures and contemporary portraits of his favourite companion and lover, Antinous. The emperor visited the land of the pharaohs as a tourist in AD 130 with his wife Sabina, his sister Paulina, his beloved Antinous, and the imperial court, which included the court poet Julia Balbilla. Upon reaching Egypt from Judaea, Hadrian visited the tomb of Pompey the Great near Pelusium.

He spent some time in Alexandria, where he restored the Temple of Serapis and dedicated a statue of the Apis bull to Serapis. He also went hunting in the Libyan desert with Antinous, an event that the Alexandrian poet Pancrates immortalised in Greek verse in a flattering poem. The imperial party then proceeded up the Nile to Heliopolis, Memphis, Oxyrhynchus and Hermopolis, near which Antinous mysteriously drowned in the Nile during the Osiris festival. Deeply affected by his death, Hadrian founded the city of Antinoopolis near the site where Antinous died. He deified the young boy and created a new Egypto-Roman cult devoted to his worship that spread throughout the Empire.

The Antinoeion

At Tivoli, Hadrian erected a memorial monument to Antinous with numerous statues of the Bithynian boy. These portraits depicted Antinous wearing the traditional headdress of an Egyptian pharaoh, identifying him with Osiris, the Egyptian god of the Underworld who drowned in the Nile and was reborn from its waters. The Antinous monument, now dubbed the Antinoeion, comprises a sacred precinct with two small temples facing each other in front of a semi-circular colonnaded exedra in the middle of which was another temple.

An obelisk dedicated to Antinous, covered with reliefs and hieroglyphs and now standing on the Pincian Hill in Rome, is believed to have stood between the two temples and marked Antinous’ grave. The monument was bordered by palm trees, evoking a bucolic Egyptian landscape. The excavators of the Antinoeion, Z. Mari and S. Sgalambro, have argued that the monument is not simply a mausoleum, cenotaph or cult site but instead that it is the actual tomb of Hadrian’s favourite.

In 2002, excavations at the Antinoeion uncovered several Egyptianizing sculptures and architectural fragments, including a statue of the pharaoh Ramses II (ruled 1279–1213 BC), a small head with pharaonic headgear, and a statue of Horus wearing the double crown of Egypt. Other statues found in the mid-17th and 18th centuries, such as the marble statue of Antinous-Osiris, two telamons in red granite and the fifteen black marble statues of Egyptian gods and priests now in the Gregorian Egyptian Museum of the Vatican, which probably originated from the Antinoeion. These statues were previously assigned to the so-called Serapeum.

A bell-shaped grey granite crater with Egyptianizing scenes said to be from the Canopus has also been reallocated to the Antinoeion. The vase displays a frieze with four Egyptian worship scenes separated by an obelisk with a scarab-like finial and a large feline protome (which may refer to the goddess Bastet). The two human figures, one bearded and the other a young male in Pharaonic clothing, can be identified as Hadrian and Antinous. The frieze depicts offerings to a deity and displays sacred symbols such as a phoenix and snake. It is thought to be linked to the Sed festival, a ceremony that celebrated the passage and renewal of kingship. Here, royalty is passed on by Hadrian to Antinous through the offering of the ka (“soul” or “spirit”).

Other crossovers between Egyptian and Greco-Roman art can be seen in the colossal bust of a veiled female goddess identified as Isis-Sothis Demeter. Each goddess embodies the attributes of fertility, agriculture and the cyclical nature of life. The bust was found in the Palaestra, a monumental complex of several buildings decorated with exotic marble columns and mosaic flooring. It contained more Egyptianizing works of art, including busts of Isiac priests and a sphinx statue.

Astronomy and Astrology

Hadrian also had a great interest in astrology. Recent archaeo-astronomical research at the site of the Antinoeion has shown that the Emperor designed the tomb of his beloved Antinous with astronomical alignments.[7] The main axis of the Antinoeion was oriented toward sunrise on the summer solstice. Additionally, the solar alignments of one of the temples included the winter solstice and the birthdays of Hadrian (January 24) and Antinous (November 27). A previous research had already established an astronomical orientation of the parts of Hadrian’s Villa known as the Accademia and Roccabruna.[8]

The complex, located at the Villa’s highest and most isolated part, is oriented along the two solstitial axes, an alignment towards dawn on the winter solstice and sunset on the summer solstice. The Roccabruna was a building probably dedicated to the Egyptian goddess. It was a two-storey round tower with a Doric tholos on top and a dome with a cupola below. On the summer solstice, the sun sets in the centre of the main door and illuminates the niche on the opposite side, where a statue of the goddess Isis probably once stood. In the ancient Roman world, the traditional date of the summer solstice was June 24, and that day was sacred to Fors Fortuna, a goddess associated by the Romans with Isis. The iconography of the Roccabruna’s decoration perfectly aligns with the cult of the Egyptian goddess, as the base of a candelabrum bearing the symbols of Isis was discovered there.

Art Dispersed

Today, when visiting Hadrian’s Villa, we can only partly comprehend its opulent embellishments. The Villa once contained hundreds of sculptures, but many were removed and repurposed as building materials for churches in Tivoli during the Medieval period. In the 16th century, Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509–72) commissioned the Villa d’Este and had much of the remaining marble and statues in Hadrian’s Villa removed to decorate his own.In the 17th and 18th centuries, during the Grand Tour, the Villa attracted treasure hunters and art collectors, leading to the scattering of its sculptures to museums around the world. The only remaining sculptures at the Villa are replicas around the Canopus, with the originals housed in the Mouseia just behind it. Everything else is gone. One should visit the museums in Rome, Madrid, Paris, Berlin, or Copenhagen to see the masterpieces from Hadrian’s Villa – or simply enjoy from a distance the images that illustrate this article.

Carole Raddato is an ancient history enthusiast and self-taught photographer. She runs the photo-blog Following Hadrian, which documents her travels in the footsteps of the Roman emperor Hadrian. She has previously written for Antigone about sculptures of Antinous, and can be found on Twitter, Instagram and Flickr.

Further Reading

More photos of the treasures of Hadrian’s Villa can be found on the author’s Flickr Photostream.

See also the Digital Hadrian’s Villa project created by Bernard Frischer, Marina De Franceschini’s Villa Adriana, and Thorsten Opper’s lecture “Sculptures from Hadrian’s Villa during Age of the Grand Tour”.

William L. MacDonald and John A. Pinto, Hadrian’s Villa and Its Legacy (Yale UP, New Haven, CT, 1995).

Benedetta Adembri, Hadrian’s Villa, trans. Eric De Sena (Electa, Milan, 2000).

Benedetta Adembri and Elena Calandra, Adriano e la Grecia: La mostra (exhibition catalogue, Electa, Milan, 2014).

Benedetta Adembri, Suggestioni Egizie a Villa Adriana (exhibition catalogue, Electa, Milan, 2006).

Marina De Franceschini, Villa Adriana. Mosaici, pavimenti, edifici (“L’Erma” di Bretschneider, Rome, 1991).

Notes

| ⇧1 | This is the name given to a collection of, mostly late and falsified, biographies of Roman emperors from Hadrian to Carinus (ruled 283–5), written in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. Some of the biographies are believed to be more reliable than others, including the life of Hadrian. For more information see here. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | There were four major schools of philosophy at Athens: the gymnasia of the Academy (founded by Plato) and the Lyceum (founded by Aristotle), Epicurus’ Garden, the school of the Epicureans, and Zeno’s Stoa Poikile where the Stoics met. |

| ⇧3 | Hadrian was obsessed with architecture and loved designing great buildings, in Rome and in cities across the empire, building more than any other emperor. See further Mary T. Boatwright, Hadrian and the City of Rome (Princeton UP, NJ, 1987) and Hadrian and the Cities of the Roman Empire (Princeton UP, NJ, 2000). |

| ⇧4 | Donato Attanasio, Matthias Bruno, Walter Prochaska & A. Bahadir Yavuz, “The Asiatic marbles of the Hadrian Villa at Tivoli,” Journal of Archaeological Science 40.12 (2013), available here. |

| ⇧5 | Opus vermiculatum (in Latin, “worm-like work”) is a laying technique of making pictorial mosaics with minute tesserae, generally used for emblemata, or central figural panels. |

| ⇧6 | See here for further information. |

| ⇧7 | Bernard Frischer, Georg Zotti, Zaccaria Mari and Giuseppina Capriotti Vittozzi, “Archaeoastronomical experiments supported by virtual simulation environments: Celestial alignments in the Antinoeion at Hadrian’s Villa,” Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 3.3 (2016) 55–79, available here. |

| ⇧8 | Marina De Franceschini and Giuseppe Veneziano, “The symbolic use of light in Hadrianic architecture and the ‘Kiss of the Sun’,” Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies 6.1 (2018) 111–38, available here. |