Mateusz Stróżyński

In the fourth section of his poem ‘Little Gidding’, T.S. Eliot writes:

The dove descending breaks the air

With flame of incandescent terror

Of which the tongues declare

The one discharge of sin and error.

The only hope, or else despair

Lies in the choice of pyre or pyre—

To be redeemed from fire by fire.

Who then devised the torment? Love.

Love is the unfamiliar Name

Behind the hands that wove

The intolerable shirt of flame

Which human power cannot remove.

We only live, only suspire

Consumed by either fire or fire.

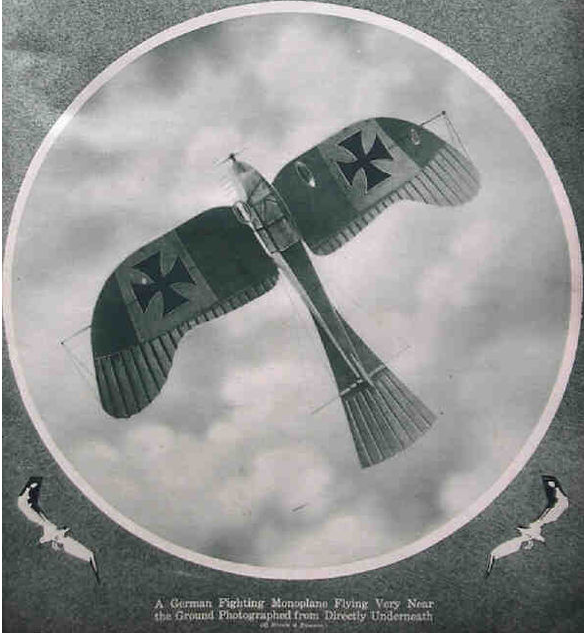

In an earlier part of the poem Eliot calls a German plane bombing London “the dark dove with the flickering tongue”; some scholars believe he alludes, anachronistically, to the German war aircraft Taube (“the dove”), used in WWI. Indeed, Eliot wrote ‘Little Gidding’, the last part of his Four Quartets, in 1941; but he attributed his difficulties to the German air raids on London. However, the dove is also the common symbol of the Holy Spirit, and Eliot here invokes His fiery descent at Pentecost. Even the phonetic similarity of “incandescent” to “descent” seems to be no mere accident.

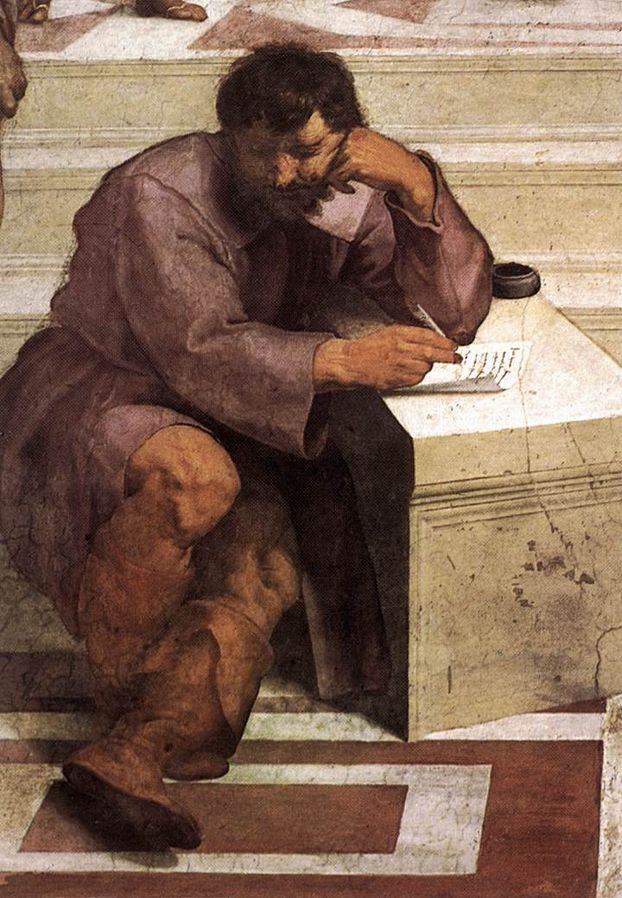

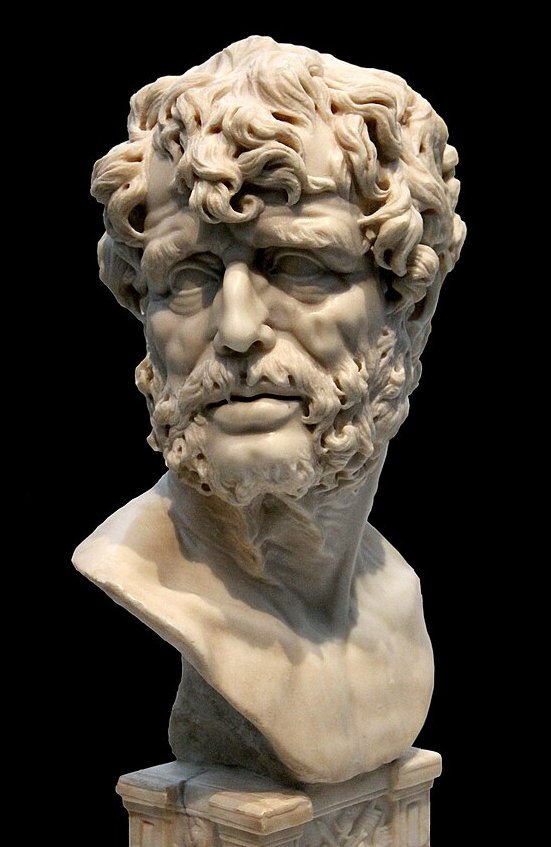

But Eliot brings in yet another reference here, namely to Heraclitus of Ephesus. The presence of the pessimistic sage from Ephesus looms over the entire Four Quartets, because, apart from various echoes of Heraclitean sayings, Eliot chooses two of his fragments as the epigraph to the entire cycle: τοῦ λόγου δὲ ἐόντος ξυνοῦ ζώουσιν οἱ πολλοί ὡς ἰδίαν ἔχοντες φρόνησιν (DK fr. 2, “Although logos [knowledge or reason] is common, the many live as if they had a wisdom of their own”) and ὁδὸς ἄνω κάτω μία καὶ ὡυτή (DK fr. 60; “The way upward and the way downward is one and the same”).

Thus, the reference to the fiery descent of the dove in ‘Little Gidding’ IV invokes Heraclitean fire as the symbol of the First Principle or the Logos: “This cosmos, which is the same in all, no-one of gods or men has made, but it was always, and is, and shall be an ever-living fire, kindled and put out according to measure” (fr. 30). For Eliot, however, as is emphatically not the case with Heraclitus, this is intimately linked to human history, which is for him a history of sin and death, of which war is a prominent example.

Yet for the sage of Ephesus, war is primarily a metaphysical, cosmic principle: “War is the father of all things and the king of all things, and some it has shown to be gods, and some men; some it has made free, and some slaves” (fr. 53); also, “one must know that war is universal, and that justice is strife (Greek ἔρις, eris), and all things are made and destroyed by strife” (fr. 80). This cosmic war, however, doesn’t lead to mindless destruction; it doesn’t shatter the structure of being. Nor does it cause chaos, because everything is ruled by the eternal harmony of the Logos.

Charles Williams, a friend of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, who was also one of Eliot’s favourite authors and literary protégés, published in 1939 – on the very threshold of war – a theological book entitled The Descent of the Dove: A Short History of the Holy Spirit in the Church. Eliot has even attributed his beautiful image of “the still point of the turning world” (in ‘Burnt Norton’ I) to Williams’ influence. When Eliot meditates on his own “descent of the dove” in ‘Little Gidding’, he sees in it a symbol of the metaphysical order of Heraclitus, in which fire descends to become air, air descends to become water, water descends to become earth. It is also the death of fire to become air and the death of air to become water, while, conversely, the birth of air is the death of fire, and the birth of water the death of air.

In ‘Dry Salvages’ III Eliot says, in a Heraclitean manner, “the time of death is every moment.” It is “the way down”, the way of destruction and dying, and of cosmic, divine warfare. In ‘Little Gidding’ II the first three stanzas end also with Heraclitean refrains: “This is the death of air,” “This is the death of earth,” “This is the death of water and fire.” Eliot claims there is justice and meaning to the death and life of the cosmos, and it is the Logos Himself; Heraclitus suggests even that there is a dimension of judgment in this destructive descent of fire: “Fire, when it comes upon all things, will judge (κρινεῖ, krinei) and lay hold of them” (fr. 66).

Eliot, in the manner of the Church Fathers (and, also, of Williams, Tolkien or Lewis), can read Heraclitus’ obscure utterings as vague premonitions of the Christian experience of Pentecost. When the Mother of God and the Apostles were gathered in the Upper Room, the Holy Spirit descended upon them in the form of tongues of fire (Acts 2:1–4). In Eliot’s imagination, however, the Spirit doesn’t breathe softly, as in the theophany experienced by Elijah (1 Kings 19:12), where the prophet hidden in a cave witnesses the wind, the earthquake, and the fire; God, however, is not recognized by him in those three Heraclitean elements, but rather in “a still small voice”. In Eliot, the Dove doesn’t have a gentle nature; on the contrary, She reveals Herself in all Her terrifying power, precisely in wind, earthquake, and fire, and in the specific form of a historical cataclysm of war. It is not a dove of peace, but a judging dove of war.

The Heraclitean theme of the judgement of fire (fr. 66) is fused here with the Biblical images of God as a “consuming fire” (Deut 4:24) and a “refiner’s fire” which will “purify the sons of Levi” (Ml 3:2), as beautifully rendered by G.F. Handel in one of the arias from his Messiah:

Eliot claims that the descent of the terrible Dove brings “the one discharge of sin and error”. It is quite a bizarre picture: war becomes, in some incomprehensible way, identical to Pentecost. But despite our subconscious assumptions that the Holy Spirit is a gentle and tender Dove, the Lord announces at the Last Supper: “And when he is come, he will reprove the world of sin, and of righteousness, and of judgment: Of sin, because they believe not in me; Of righteousness, because I go to my Father, and ye see me no more; Of judgment, because the prince (ἄρχων, archōn) of this world (κόσμου τούτου, kosmou toutou) is judged” (John 16: 8–11). The coming of the Dove is another victorious battle in the ongoing campaign against “the archōn of this world”, that is, the Enemy, who had been judged and defeated on Golgotha, but whose power will be further weakened by Pentecost.

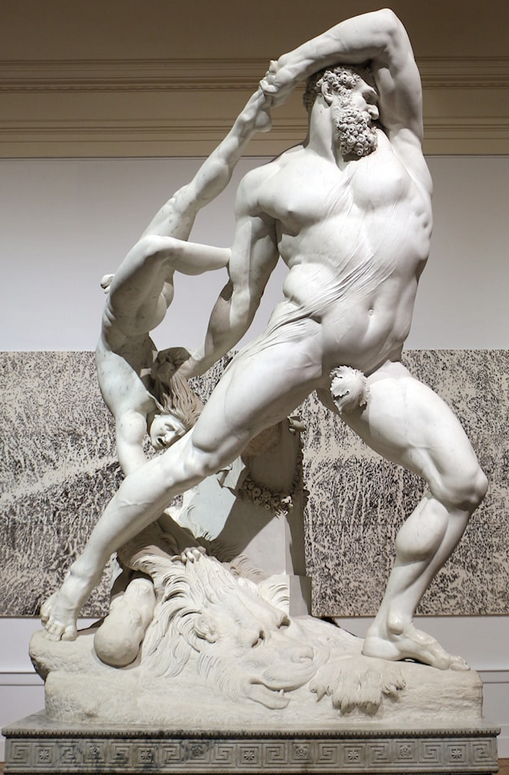

The key metaphor of the first stanza of ‘Little Gidding’ IV is “the choice of pyre or pyre”. Already here Eliot alludes to the death of Hercules, which becomes the central point of the second stanza. He uses, in particular, the tragedy Hercules Oetaeus (Hercules on Mt Oeta), attributed to Seneca the Younger. Fire, as I will show shortly, is one of the central symbols of this play, but it appears already in Sophocles’ tragedy Trachinian Women, which also describes the death of the hero on a pyre.

When Hercules (in Greek, Herakles) falls in love with the princess Iole, his wife Deianira tries to win back his love by using the blood of centaur Nessus, who promised her that the blood, aided by incantations, will be able to secure the love of her husband. Deianira sends a shirt dipped in this blood to Hercules and, when she finds out that Nessus lied to her and that this was in fact poison, she kills herself.

Sophocles didn’t depict any apotheosis of Hercules (who is a rather repugnant character in his tragedy) but he does, nonetheless, compare love to a flame several times in the Trachiniae (Women of Trachis, 103–11, 368, 463, 476–7). We even encounter the dove in this play – or, more precisely, two doves, which are said to utter prophecies at the oracle of Zeus in Dodona (169–72). The doves in Sophocles foreshadow the end of Hercules’ labours and his release from suffering, and their prophetic character resonates with a Christian view that the Holy Spirit locutus est per prophetas (“has spoken through the prophets), as the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed has it. In Eliot, the Dove comes down to “declare” the end of our labours and “one discharge from sin and error”.

However, it is Hercules Oetaeus, not Trachiniae, that Eliot is here using as his source. He was well acquainted with Seneca’s tragic corpus, and wrote two excellent essays on it.[1] The importance of fire in Hercules Oetaeus is due to the fact that, for the Stoics, the Logos or God was nothing else than intelligent fire. They also called it πνεῦμα (pneuma), which in turn is the word used for the Holy Spirit in the New Testament. Moreover, for the Stoics, Hercules was considered the model of the Stoic sage, and Seneca himself wrote about him in that way (De Constantia sapientis (On the Firmness of the Wise Man) 2.2.1; De Beneficiis (On Benefits) 1.13.3).

In Hercules Oetaeus,fire is repeatedly used as a metaphor for the passion of love (249–50, 280, 285–6, 310–11, 339, 346, 351–77, 479, 554–7). Deianira says that “love will be the ultimate work of Alcides” (473), unwittingly prophesying that her jealous love will kill her own husband. In all his works so far Hercules has been victorious, but in this his greatest work he was to be finally defeated by the god of love. As Virgil put it so unforgettably: omnia vincit amor (“Love conquers all”, Ecl. 10.69).

At the end of Sophocles’ Trachiniae, Hercules’ son, Hyllus, says that the gods are cruel, and in fact both this tragedy and the later Latin version, describe a kind of “divine violence”. Sophocles ends the tragedy by a comment from the Chorus, who says of the countless deaths and sufferings sent by the gods, “in all of that there is nothing that is not Zeus” (κοὐδὲν τούτων ὅ τι μὴ Ζεύς, 1278). Again, it sounds like a premonition of the descent of the terrible, fiery Dove, bringing judgement. In Hercules Oetaeus Deianira wants to teach Hercules how to love and be faithful, but the fire of her love is transformed into a very real fire that will overcome the dissolute fire of Hercules’ erotic passions in a way that she couldn’t have foreseen. Thus the fire becomes a symbol of divine love transforming Hercules, violently and against his will, into a god.

And here we have Eliot’s “choice of pyre or pyre,/ to be redeemed from fire by fire.” Fire represents the passions from which Hercules needs to be freed and purified and, at the same time, it stands for the fiery, divine Logos, which will burn them out. The description of Hercules at the stake must, in the eyes of a Christian reader, evoke associations with the passion of the Logos made flesh: “He lay peacefully and was attentively searching through the sky, whether his father might look down upon him from any part of it. Then he said, stretching out his hands: ‘Wherever you look from, father, upon your son, I beg you…’” (1693–7). It resembles Christ’s habit of looking up towards Heaven, towards His Father, while praying (e.g. John 11:41; 17:1).

The hero in Hercules Oetaeus makes a good “choice of pyre”, because he accepts his suffering and death voluntarily and asks for the fire to be kindled (1715ff.). He prays to Jupiter, his divine father: “If the crimes exist no longer, take this spirit, I pray, up to the stars” (1703–4) At the very moment of death he will add: “My father is already calling me and opening Heaven. I am going, father” (1725 –6). When we hear this spiritum admitte, it’s hard not to think (with Eliot, it seems) about the last words of Jesus: “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit” (Luke 23:46; cf. Ps 31:6), and the image of open Heaven brings to mind the open gates in Psalm 24:7 (“be ye lift up, ye everlasting doors; and the King of glory shall come”).

This is not the end of these striking parallels. When Hercules’ mother, Alcmena, mourns her son as a mater dolorosa (grieving mother), the hero speaks from Heaven, announcing to her that she shouldn’t weep, because he lives (1940–3), like the angel who says to the weeping women: “He is not here, for he is risen” (Matt 28:6). And when Hercules commands his mother to understand that he has returned to his divine father, we can think of Jesus telling Mary Magdelene not to stop Him, because He is returning to His Father (John 20:1–18). Finally, when Hercules explains to her what his death by fire accomplished: “Whatever in me was yours and mortal, the fire has taken away” (1963–8), we can remember: “For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality” (1 Cor 15:53).

Eliot says that the torment was devised by Love, and calls Love “the unfamiliar name/ behind the hands that wove/ the intolerable shirt of flame/ that human power cannot remove.” In Hercules Oetaeus this has a literal meaning, because Deianira is the name of the one who wove the shirt of flame. But for Eliot Deianira becomes a symbol of God, who weaves for His unfaithful beloved the shirt of flame to change her heart. When we turn away from Him, we fall prey of the fire of our passions and sins which, in the end, becomes the fire of Hell. When we turn towards Him, this fire becomes the purifying pyre of Hercules, making gods of us. We “only live, only suspire/ consumed by either fire or fire” and we have to make a choice “of pyre or pyre”.

Indeed, in our own culture “Love is the unfamiliar Name”. Eliot’s ‘Little Gidding’ IV, drawing on the Classical and Christian traditions, challenges the sentimental, pink-coloured “love” of Hollywood movies and pop songs. His terrible Dove or divine Deianira has very little to do with that. But whoever has really loved even one person in his or her life, knows well that love is painful and terrible. It is destructive like the Heraclitean fire; it descends upon us and our world like judgement or a German air raid. Not in order to torment us pointlessly, but in order to liberate us from our pride, envy, greed, sloth or lust. In order to transform us into gods, it has to kill us first; otherwise, how would “this mortal put on immortality”?

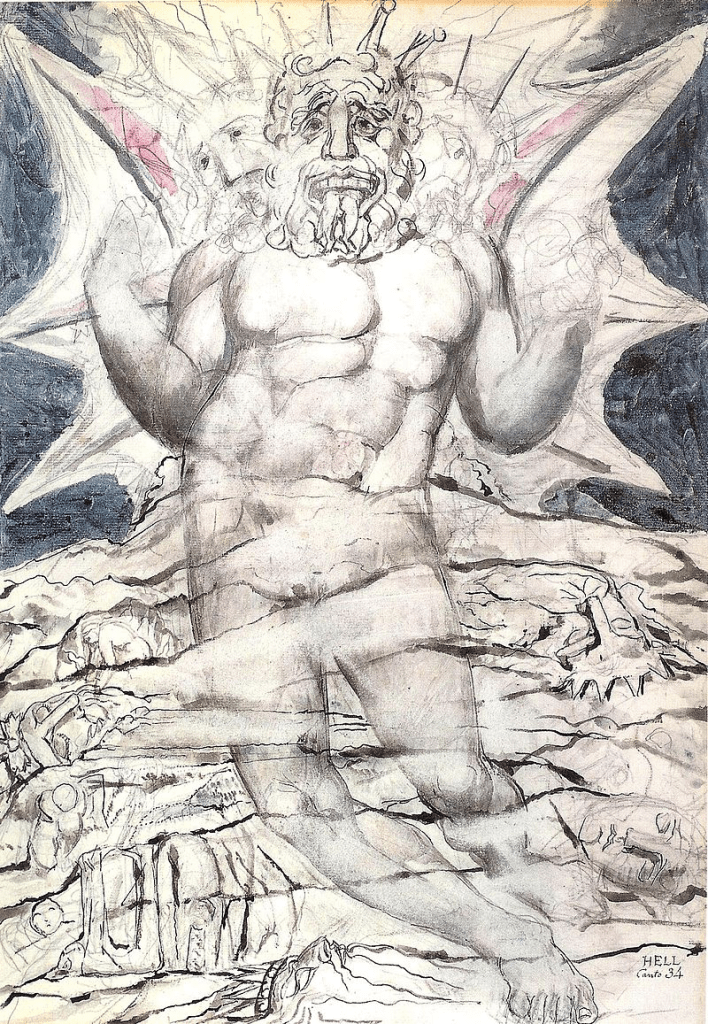

Ultimately, for Eliot, it is Christ, the Logos made flesh, who hides behind the figure of Hercules on the pyre. But, unlike Hercules, He is not only on a pyre; He is Himself the fire in which He is burning. Clement of Alexandria believed that it is the Logos that was shining in the Burning Bush of Exodus 3:14 (Paed. 2.8), so we might say that the Cross is a pyre, too. And Mount Oeta is an image (τύπος, typos, as the Church Fathers would say) of Golgotha. Venantius Fortunatus saw that clearly, when he wrote in the opening of his beautiful hymn Vexilla regis prodeunt (The Royal Banners Forward Go): “the mystery of the Cross is blazing” (fulget crucis mysterium). Eliot uses his Hercules as a representative of the everyman and points out that our existential situation is the compulsion to choose between two pyres and two fires. There is no way out, unless we destroy all capacity to love in ourselves and become icy-cold, like Lucifer in Dante’s Divine Comedy – a poem that Eliot adored.

The impossibility of removing our “imperishable shirt of flame” can be read on different levels, like all the metaphors employed by Eliot in ‘Little Gidding’ IV. It can represent our sinful nature, our restlessness, or something like the Buddhist dukkha, “suffering” in the sense of insatiability and dissatisfaction with all perishable things. But, at the same time, it represents God Himself. At the end of his ‘Fire Sermon’ (the third part of his pre-conversion poem, The Waste Land, 1922), Eliot alludes to St Augustine’s Confessions (3.1.1), invoking the universal image of insatiable desire for the transient things: “To Carthage then I came/ Burning burning burning burning.”

And he knows well that the particular Biblical verse that Augustine read in a garden in Milan and which converted him (8.12.29) was: “Put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to fulfil its lusts.” (Rom 13:14). For Eliot, then, the “imperishable shirt of flame” that transforms us into gods is Christ Himself. The early Fathers saw the symbol of Christ in the sun, with which the Woman in Revelation 12 was clothed, and the Woman was believed to signify not only the assumed Mother of God, but also the Mother Church. We who are members of the Church are clothed in the indomitable heat and brilliance of the divine Sun and that is why “we only live, only suspire/ consumed by either fire or fire.” As St Paul also says: “whether we live, we live unto the Lord; and whether we die, we die unto the Lord: whether we live therefore, or die, we are the Lord’s” (Rom 14:8).

We will burn like Hercules anyway. We may burn in our desires, passions, sins, and from the insatiability that consumes us, despite our efforts to deny it; then, we may discover that we have been living in the fires of Hell all our life and rejecting the possibility of escaping them. We may also burn in the purifying, sanctifying, deifying love of God, whose relentless sunshine can eventually burn all that is evil in us and transform us into pure light; then we may discover that, for all our life, we have been living in the fires of Purgatory, which, in the end, reveal themselves to be the fiery Love of the Sun of Justice (Malachi 4:2).

Mateusz Stróżyński is a Classicist, philosopher, psychologist, and psychotherapist, working as an Associate Professor in the Institute of Classical Philology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. He is interested in ancient philosophy, especially the Platonic tradition. His new book Plotinus on the Contemplation of the Intelligible World is forthcoming through Cambridge University Press.

Notes

| ⇧1 | “Seneca in Elizabethan Translation,” and “Shakespeare and the Stoicism of Seneca,” in T.S. Eliot, Selected Essays (Faber & Faber, London, 1966) 65–106 and 126–40. |

|---|