Jeffrey M. Duban

Homeric alliteration occurs at all levels: two- and three-word combinations, full lines, numbers of lines, and entire passages, with more than a single consonant or vowel sound often in play. Alliteration in oral poetry does not surprise, both because oral poetry exists for the ear rather than the eye and because similarities of sound aid memory and recitation.

Homeric alliteration is more pervasive than recognized, and significantly more integrated or textured than the stark word-initial alliterations of Beowulf and other early English poetry – stark, because in largely mono- and disyllabic Old English, alliteration falls predominantly at word beginning, whereas in polysyllabic Greek it appears distributively. Little can better reveal the signature artificiality of the Kunstsprache (“art language”) that is Homeric Greek than its insistent, yet often surprising, alliterations. These bind and secure the poetic line, line group, or passage, often creating or reinforcing meaning (the sound-sense corollary). Alliteration enhances phrase and passage movement. It is ornamental but never trivial, gratuitous, or tongue-twisting. Correctly done, it delights; and the better done, the less apparent, as the art in art is concealment.

Alliteration at its best is an adjunct of meaning – a matter of poetic decorum, a means by which sound reflects and reinforces sense. Well-known Homeric examples include the Cyclops’ dashing of Odysseus’ companions’ brains (against the floor of his cave) – with its repeated “κ/k” and “χ/kh” sounds – before dismembering and devouring them (Od. 9.287–91); conversely, the liquid-flowing sounds of the Sirens’ song, resisted by the mast-bound Odysseus (Od. 12.184–91). In both cases, sound reflects and reinforces sense. The technique analogizes sound and sense, creates coherence between them. As Alexander Pope famously observes in An Essay on Criticism (1711), “The sound must seem an echo to the sense.”

As alliteration pleases, so does it persuade. The technique may reflect the gift of an individual poet, or as in the case of Homer and other ancient traditional poetries, the end point or summation of countless recitations, each developmental in its way, each lighting on more dictionally decorative and alliteratively pleasing expression. It is the rich polysyllabism of Homeric Greek that makes it so. The greater the number of syllables, the greater the alliterative potential. The credible translation of Homer reasonably reflects what, in its own way, is of the essence of Homer.

Toward that end, each line of my translation contains at least one di- or polysyllabic word, even if only a disyllabic conjunction or preposition, as sometimes occurs. Most lines contain at least two polysyllabics; many, more than two. The resultant polysyllabism heightens rhythmic movement, even as it increases alliterative potential. Polysyllabism further signals prosodic maturity. Indeed, from the mid-20th century to date, the principal disappointment of Homeric (and Virgilian) free-verse (and even blank-verse) translation has been a deadening mono- and disyllabism. There is, of course, no fully Greek-replicating polysyllabism in English – largely because English is, or has evolved into, a non-inflected language, lacking word endings. English is also less compound-prone and ultimately very much simpler than Greek (Archaic, Classical, or Modern). English, moreover, retains its original Anglo-Saxon/Germanic stock of mono- and disyllabic words.

Yet polysyllabism is possible in translation, thanks largely to numerous Greek and Latin loan words. Polysyllabism in the English translation of Greek and Latin is thus a kind of “giveback” to those languages to which English is significantly indebted, the circle coming round. Of course, there are numerous Greek- and Latin-derived English words that lack Anglo-Saxon-based alternatives. This only increases the case for a robust polysyllabism, though one would not know it from the current state of epic in translation. Whether through lack of initiative or imagination, many a line of Classical epic translation appears – in medical parlance – to flatline.

The alliterative gradations of Homeric Greek are set forth in my Homer’s Iliad in a Classical Translation (Part IV, §5). However, because of limitations of space, I was unable to further the discussion with the consummate alliterative illustration that follows. The bravura passage, with playful cleverness, exploits alliterative multiples in the service of sense or meaning:

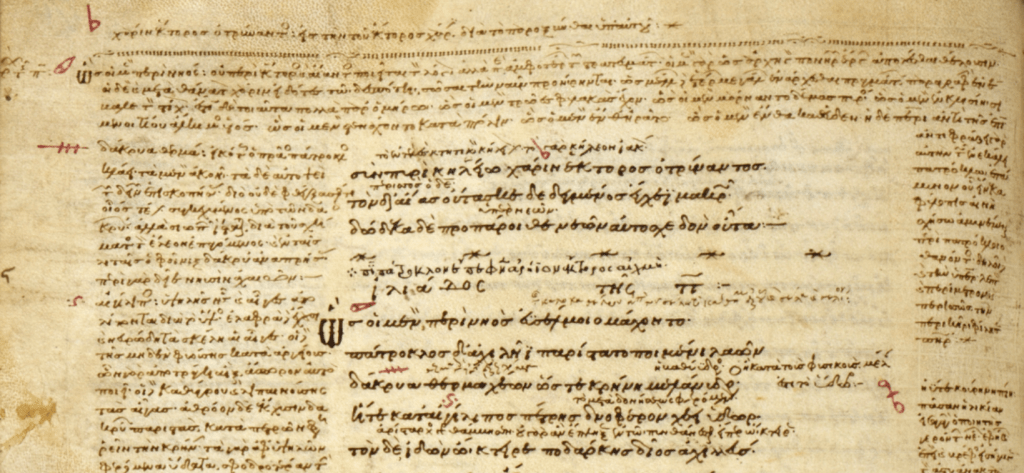

ὣς φάτο, τῷ δ᾽ ἄρα θυμὸν ἐνὶ στήθεσσιν ὄρινε,

βῆ δὲ θέειν παρὰ νῆας ἐπ᾽Αἰακίδην Ἀχιλῆα.

ἀλλ᾽ ὅτε δὴ κατὰ νῆας Ὀδυσσῆος θείοιο

ἷξε θέων Πάτροκλος, ἵνά σφ᾽ ἀγορή τε θέμις τε

ἤην, τῇ δὴ καί σφι θεῶν ἐτετεύχατο βωμοί,

ἔνθά οἱ Εὐρύπυλος βεβλημένος ἀντεβόλησε

σκάζων ἐκ πολέμου…

hōs phato, tō(i) d’ ara thūmon eni stēthessin orīne

bē de theein para nēas ep’ Aiakidēn Achilēa.

all’ hote dē kata nēas Odussēos theioio

hixe théōn Patroklos, hina sph’ agorē te themis te

ēēn, tē(i) dē kai sphi theôn eteteuchato bōmoi

entha hoi Eurupulos beblēmenos antebolēse

skazdōn ek polemou…

So speaking he roused

Patroclus’ spirit, and sprinted he the distance

Of the ships to Achilles, Aeacus’ scion.

But when in his running Patroclus gained the ships

Of godlike Odysseus, where convened assemblies,

And adjudications, and where altars stood built

To the gods, there met him Zeus-born Euaemon’s son,

Eurypylus, to the mid-thigh arrow-smitten,

From out the battle limping…

(Il. 11.901–9 [804–11])[1]

The passage resorts to the orthographic similarity between théō (“I run”, here inf. théein, “to run”, and pres. part. théōn, “running”) on the one hand; and theíoio “divine” (adj. gen. sing.) and theôn (“gods”, masc. gen. pl.) on the other. Here we deal largely with playful soundalikes for their own sake, as there is no inherent association between gods and running. Gods have no need to run. The thought is comic. They simply go – often “leaping” to get underway. Once in motion, they “quickly”, even “rather quickly”, arrive. The messenger god Hermes has winged sandals. These mitigate the notion of his running or even stepping from one errand to the next, including his numerous passages as psychopomp (guide of souls) to Hades.

We thus note in the line-numbered passage above, from lines 2–5: θέειν (théein, “to run”); θείοιο (theioio, “of the divine” [Odysseus]); θέων (théōn, “runing”); and θεῶν (theôn, “of the gods”). The punning is announced by what are two (formulaically joined) thēta words, line 1: θυμόν (thūmon, “heart, spirit”) and στήθεσσιν (stēthessin, “breast”). Line 4, with θέμις (themis, “law, adjudication”) expands the semantic range, given the shared verbal root and intimate connection between law and divinity, i.e., themis and theos. The play closes in line 6 with neutral ἔνθα (entha, “there”).

Additional features show the finesse of Homeric passage work. The first plays on the difference in accentuation between θέων (théōn, “running”) and θεῶν (theôn, “of the gods”). Ιn a prose passage or conversation, the two words, stressed on different syllables, would have discernibly different intonation and, thus, meaning. Theoretically, at least, were θέων (théōn, “running”) spoken outside the hexametric line, it would have an initial syllable stress, as indicated by its accent mark. But in the Homeric line, since théōn and theôn end in omega-vowel syllables, they are necessarily stressed on that syllable, since long syllables, barring exception, are always weighted. The words’ meanings are thus here reliant on context alone.

Finally, we note the following in lines 6-7, above:

ἔνθά οἱ Εὐρύπυλος βεβλημένος ἀντεβόλησε

σκάζων ἐκ πολέμου…

entha hoi Eurupulos beblēmenos antebolēse

skazdōn ek polemou…

There the wounded [beblēmenos] Eurypylus met [antebolēse][2] him

From out the battle limping…

Noteworthy is the plenary alliteration (b-l-ē-s) and the inevitable assonance of three words containing thirteen syllables and expressing little more than the casual encounter of wounded man and friend. No sound-sense import, but mere sub-finesse in an already outstanding passage. The clincher in this last pattern, however, is the embedded semantic association in Greek – call it an “in-joke” – between the words “wounded” and “met”, both formed on Greek ballō, “I throw” (Eng. ball, ballet, ballistic). Thus, when met hardby an object, one is wounded. Here, a wounded man (beblēmenos) meets (antebolēse) his friend whose name – Eurypylos – contributes to an alliteratively rich and punning three-word unit. Further noted is the play between “Eurupulos” and polemou, “from battle”.

A second example entails alliteration with purposefully archaizing intent. It is nothing less than the opening of the Odyssey itself. In fact, it entails the last line alone of the poem’s opening, which sends an alliteratively unequivocal message – as if to say, this is, and will be treated as, an antique poem, even in what Homeric audiences considered their “modern” times. The poet begins by invoking the Muse to tell of Odysseus, the “man of many turns”, who suffered much on both land and sea upon his return from Troy. The adventures are many, so the poet ends the invocation as follows:

τῶν ἁμόθεν γε, θεά, θύγατερ Διός, εἰπὲ καὶ ἡμῖν

tōn hamothen ge theā, thugatēr Dios, eipe kai hēmin

From some one of these (events), goddess, daughter

of Zeus, tell us also (Od. 1.10)

The second word ἁμόθεν (hamothen) is compounded of hamos (“some, someone, some one, the archaic equivalent of otherwise Homeric and Classical tis, “some, someone”) and the archaic suffix -θεv/-then. The doubly-marked archaic compound in the poem’s very invocation signals a plentiful antiquity, even as it sounds alliteratively smart or up to date with the addition of two further θ/th sounds in the same line (tōn hamothen ge theā, thugatēr). Such contrivance is all in the epic “day’s work,” this one appearing emphatically at the outset. The word hamothen is, further, a hapax, with no instance of the unsuffixed hamos anywhere in Homer. Note also the secondary “γ/g” alliteration: hamothen ge theā, thugatēr. The singular choice of hamothen could thus be no more purposeful in its archaizing, alliterative, and metrically galloping effect (five dactyls with final spondee).

One thinks of the opening line of Spenser’s The Faerie Queene: “Lo I the man, whose Muse whilome did maske,” where Middle Eng. whilome/whylome (“formerly”) – Old Eng. whīl /whīlum – clearly announces the archaizing intent of an epic focused on bygone knighthood. Homer exploits alliteration not only for its own sake but also to announce, in his own time, how remarkably an archaic/archaizing poet he is – in diction, style, and theme. It behooves any translation of Homer to convey whatever modicum of this it might, “be it so faint, yet clearly audible, as the cosmic microwave background trailing the Big Bang.”

An alliterative example – beyond two-to-four-word combination – that lacks counterpart in Homer, but is yet true to Homeric usage, is:

And the old man,

Peleus, chariot lord, was offering a fattened

Thigh of bull, to Zeus in thunderbolt rejoicing,

Within the court’s enclosure, and clasped a golden

Goblet, whence flowed as fellow to the offering

A fiery wine. (Il. 11.864–9 [772–5])

Or

So we departed, much aggrieved, angered for the gain

Agreed to but given not. (Il. 21.511–12 [456–7])

More extensive yet is the description of Thersites:

Then were the others still, throughout their ranks restrained,

But Thersites alone, intemperate of tongue,

Yet scoffed and bawled, disorderly, obstreperous;

Convulsed was his vernacular, availing not,

With kings inclined to quarrel; intoxicate he,

Danaan dullard and simpleton, reprobate

Of Troy, blighted his breeding; bandy-leggèd, lame

Of foot, his shoulders inward shunted toward his chest;

Pointy-headed, and sparse the tuft atop his pate;

Despisèd of Odysseus he, to Achilles

Loathsome most, for he ever importuned the twain

And against Agamemnon relentlessly railed,

Disdained of the Danaans, held in their despite. (Il. 2.216–28 [211–23])

The Thersites rendering is as artificial in its way as the Greek thēta-laden passage above. The latter is too intrinsically Greek-contrived to yield gold in translation. Conversely, the Thersites passage in Greek lacks the fullness of effect I have given it here. The result nonetheless seems right; and Homer’s technique, on balance, retained.[3]

Jeffrey Duban attended the Boston Public Latin School, where he studied Latin and Greek. Graduating from Brown University with a combined BA and MA in Classics, he went on to complete his PhD in Classical Philology at The Johns Hopkins University. After a brief university teaching career, he enrolled in law school, obtaining his JD degree from the Fordham Law School. As an attorney, he specialised in academic law.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Line numbers in parentheses are to my translation; in brackets, to the Greek text. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Antebolēse is the aorist of anti-ballo, “hit upon, meet by chance”. |

| ⇧3 | This article is in part adapted from Jeffrey M. Duban, Homer’s Iliad in a Classical Translation, a co-edition of Achilleid Books (New York, NY) and Clairview Books (West Hoathly, UK), forthcoming in Fall/Autumn 2024). |