Konstantine Panegyres

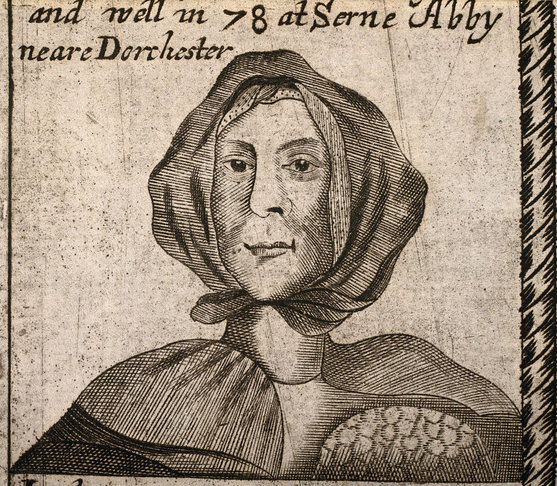

Cancer is an uneven swelling, rough, unseemly, darkish, painful, and sometimes without ulceration, and, if operated upon, it becomes worse, and sometimes with ulceration, for it derives its origin from black bile, and spreads by erosion; forming in most parts of the body, but more especially in the female uterus and breasts.

Paul of Aegina (7th century AD)[1]

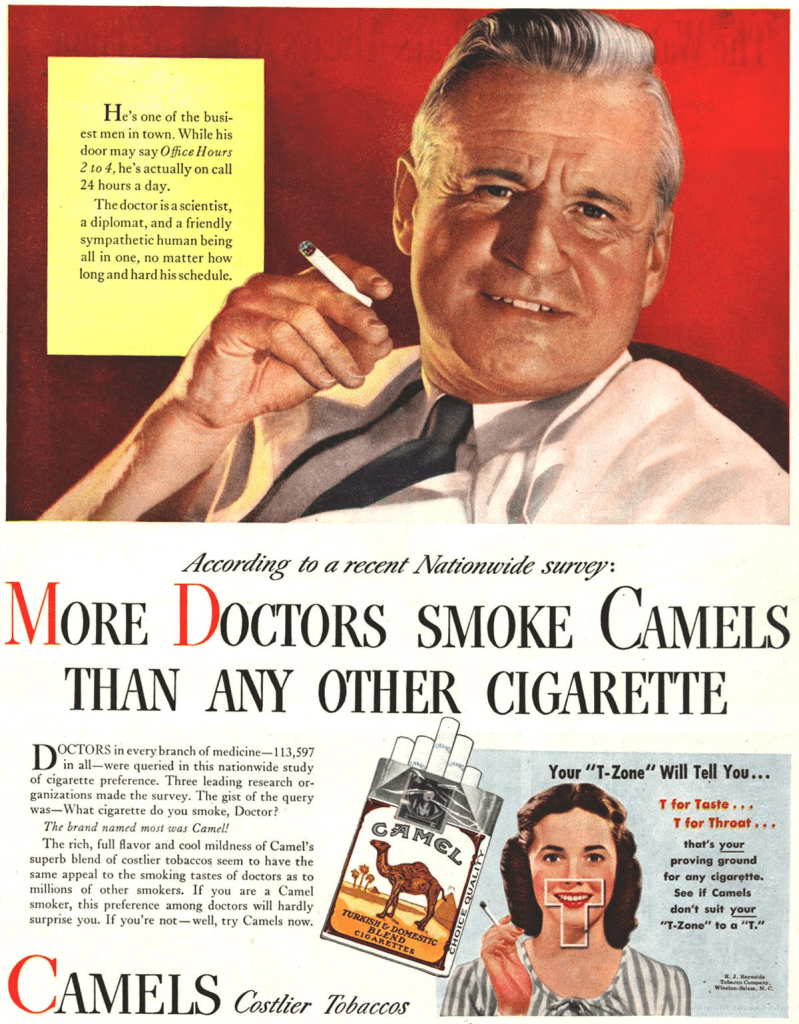

I used to live on the street where Sir Richard Doll (1922–2005), the epidemiologist, had lived when he was Regius Professor of Medicine at the University of Oxford. The front wall of the house has one of those famous English Heritage blue plaques with his name on it.

Doll is well known for having demonstrated that smoking tobacco is a cause of lung cancer. In a now famous study of the smoking habits of doctors in the United Kingdom, which was conducted over a period of fifty years, Doll showed that half of those doctors who smoked were eventually killed because of their smoking habit, whereas those who never smoked or who stopped smoking had much better health outcomes. His results did not indicate that all those who smoked got lung cancer, or that all those who did not smoke avoided lung cancer, but that smoking substantially increased the probability of developing lung cancer in the future, and so smoking must contribute greatly to a person’s chances of getting lung cancer.

While some earlier researchers had made the link between tobacco smoking and lung cancer, Doll was the first to do so on such a large and convincing scale. He himself had once been a smoker, but he stopped his habit at the age of thirty-seven once the results of his research about the ill effects of smoking began to emerge: his memorial in the Biographical Memoirs of the Fellows of the Royal Society says that “he may well have prevented his own premature death by doing so, and his work helped prevent millions of other premature deaths.”[2] I always found it very ironic that I would often see people smoking while they walked down the street past his old house.

The Name of Cancer

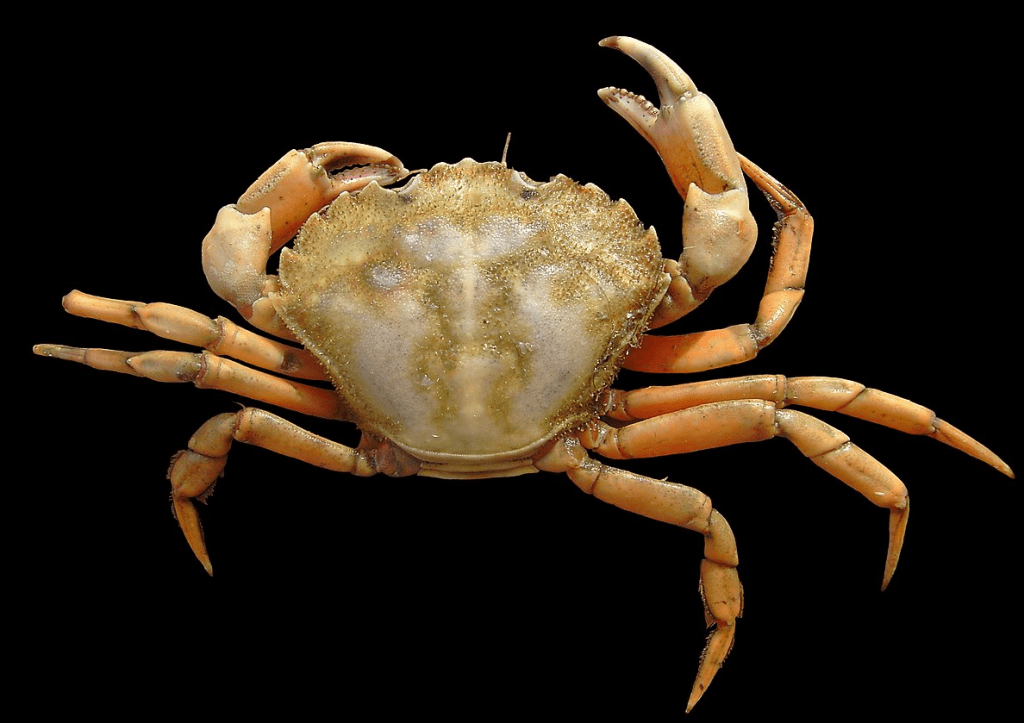

The modern medical terminology associated with this disease comes from the Greek word karkinos and Latin word cancer, both meaning “crab”. Why is the disease named after this creature? There were various explanations in antiquity.

Stephanus of Athens, a physician who lectured on medicine in Alexandria in the 7th century AD, summed it up in his Commentary on Hippocrates’ Aphorisms: “it is called karkinos (crab) either because of the aggressivity of the animal, or because the veins located in the affected part resemble tentacles, as the legs of a crab do.”[3] Paul of Aegina, a medical writer also of the 7th century AD, said something similar in his Medical Compendium:

[in cases of cancer] the veins are filled and stretched around like the feet of the animal called karkinos (crab), and hence the disease has got its appellation. But some say that it is so called because it adheres to any part which it seizes upon in an obstinate manner like the crab.[4]

The name of cancer is, therefore, a zoomorphic medical metaphor.

Such metaphors were common in antiquity. Consider some parallels: alopecia apparently received its name from the fox (alōpex), because foxes often suffer from loss of hair; [5] and elephantiasis apparently received its name either because those suffering from it resemble an elephant, or because it affects the body greatly and the elephant is the greatest of animals.[6] These zoomorphic metaphors emerged because doctors in antiquity were well aware of the similarities between human beings and animals, and so devised memorable names for diseases that were based on comparisons between the characteristics of diseases and the characteristics of animals.[7]

The Terminology of Cancer

The word καρκίνος (karkinos, crab) was not the only term used to refer to cancer; the other main term was καρκίνωμα (karkinōma, ultimately derived from karkinos). The verb καρκινόω (karkinoō) meant not just “be like a crab” but also “be cancerous”. The noun καρκίνωσις (karkinōsis) referred to the formation of a cancerous growth in the body. Doctors in Greco-Roman antiquity distinguished between ulcerated and unulcerated cancers. Ulcerated cancers were those that had broken through the skin, creating a wound; unulcerated cancers had not.

The word karkinos and related terms cannot be entirely coterminous with what we in modern times think of as cancer. Some of the conditions that were called ‘cancer’ in antiquity would surely be diagnosed differently today. The concept of cancer was associated with tumours, whereas today we know that not all cancers come in the form of tumours – blood cancer, for example. There was no specific name for the study of cancer in antiquity: it had not become a specialised area of medical inquiry. Oncology, the modern term for this, comes from the word ὄγκος (onkos): this had a wide range of meanings, but its basic meaning was “bulk, mass, body”. In ancient medicine the word was used to refer generally to various swellings and tumours in the body, but onkos did not refer specifically to cancers.

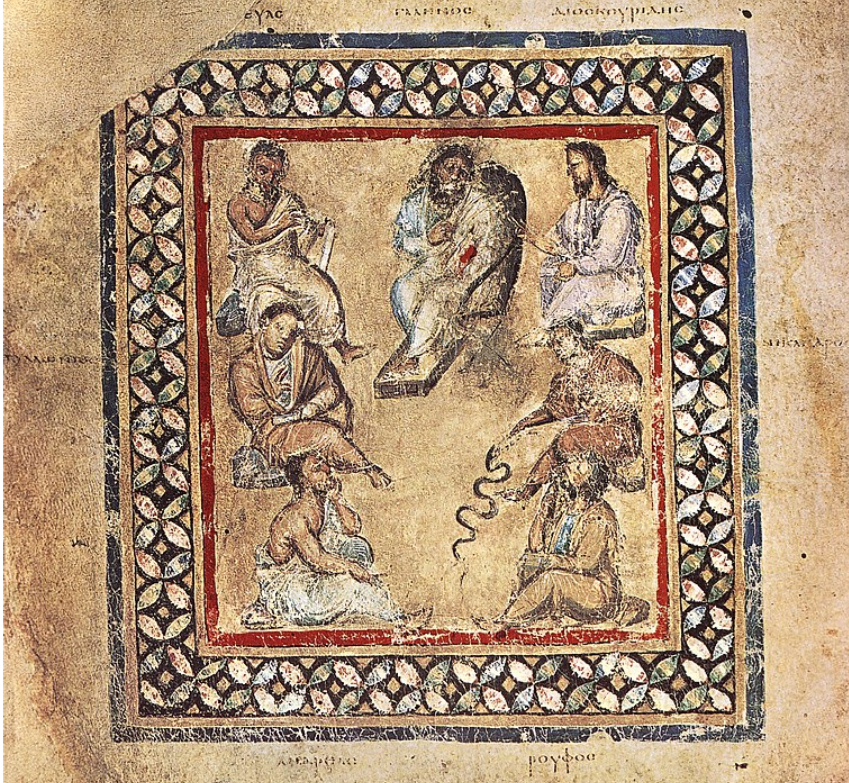

The great physician and philosopher Galen (AD 129–216) was born at Pergamum in Asia Minor, but spent much of his career at Rome working as the personal physician of the emperors Marcus Aurelius, Commodus, and Septimius Severus, while dealing with many other patients from various walks of life. Galen wrote a treatise devoted to the study of onkoi, the only such treatise to survive from antiquity. This was titled On Unnatural Swellings, and only parts of it deal with cancers.

Galen begins this work by discussing the terminology for swellings:

The word onkos refers to one of the accidents that happen to human bodies; the Greeks also use it to signify extension in length, breadth, and thickness. In addition, they sometimes call that increase which exceeds what is natural an onkos. This can be present not only in those who are suffering from a disease in some part but also in those who are healthy… This word is customarily used by the Greeks to refer to the fleshy parts in a large swelling that occur with tension, resistance, throbbing pain, heat, and redness’.[8]

An onkos, then, is a swelling of abnormal nature that arises in the body and causes discomfort.

The Cause of Cancer

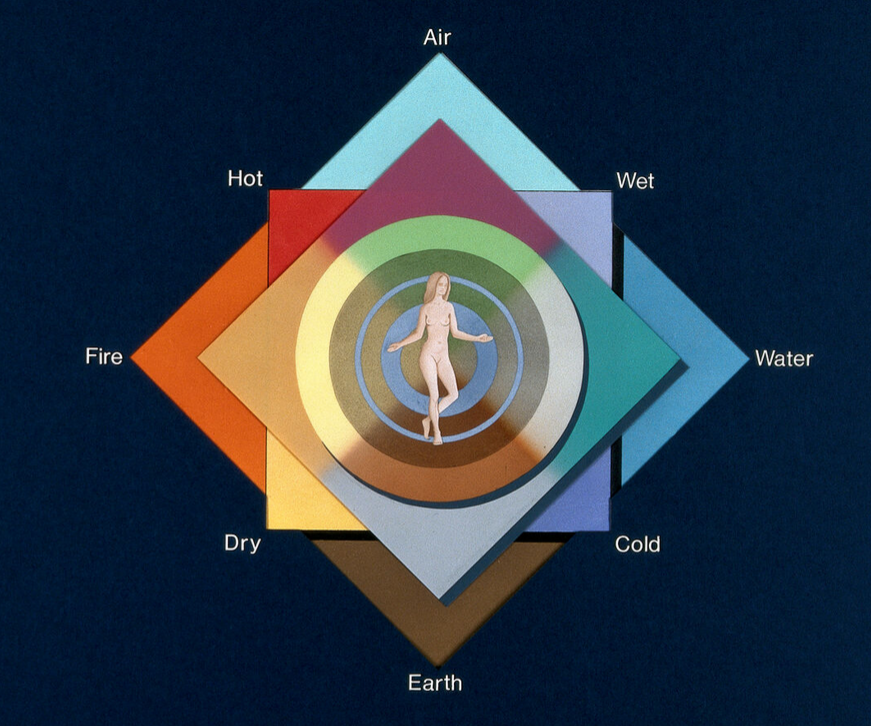

Greco-Roman doctors had a theory of humours. There were four humours – blood, yellow bile, phlegm, and black bile (this last was also known as the melancholic humour). Every person’s body required a balance of humours. This theory is found as early as the late 5th century BC, in the treatise On the Nature of Man:

The body of man has in itself blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile; these make up the nature of his body, and through these he feels pain or enjoys health. Now he enjoys the most perfect health when these elements are duly proportioned to one another in respect of compounding, power and bulk, and when they are perfectly mingled. Pain is felt when one of these elements is in defect or excess, or is isolated in the body without being compounded with all the others. For when an element is isolated and stands by itself, not only must the place which it left become diseased, but the place where it stands in a flood must, because of the excess, cause pain and distress. In fact when more of an element flows out of the body than is necessary to get rid of superfluity, the emptying causes pain. If, on the other hand, the emptying takes place into an inward part, as well as the shifting and the separation from other elements, the man certainly must, according to what has been said, suffer from a double pain, one in the place left, and another in the place flooded.[9]

The view was that when black bile becomes badly mixed with the other humours, and is isolated within the body, it can cause pernicious diseases, among them cancers. How this process led to the development of tumours, and eventually cancerous tumours, is explained by Galen in his work On Black Bile:

When black bile is on its own, it immediately creates a dark tumour, and in time what is termed cancer, for the humour then is very harsh and malignant. When it is more moderate, it eats through the skin and causes a hidden cancer that has no visible wound. So it is evident that diseases like this, and particularly cancer, stem from black bile, whenever the veins can be clearly seen as reaching to the affected part of the body, since veins absorb thick black humour. This is because nature continually tries to cleanse the blood, separating from it whatever is bad and directing it away from the important parts of the body, sometimes to the stomach and bowels, at other times to the surface of the body.[10]

As certain diseases were associated with certain humours, it was thought that diseases could be maintained or even cured if a doctor sought to make changes to the state of that humour in the body of the patient: “in healthy people each humour can be expelled if drawn out by a drug linked with this humour,” says Galen.[11] Cancer was widely associated with black bile, so making changes to the state of black bile in the cancer patient’s body was regarded by many doctors as the proper mode of treatment for cancer. As Galen explains:

it was apparently evident to the ancients that each of the purgative drugs attracts a particular humour, since the drugs which draw yellow bile are of benefit to those suffering from jaundice, whilst the drugs which are called hydragogues empty out watery discharges in dropsy, whilst those drugs which remove black bile prevent elephantiasis and cancer from growing.[12].

Not everyone agreed that black bile caused cancer. Erasistratus, the great physician active in the first half of the 3rd century BC, apparently denied that black bile was the cause of many diseases, among them cancer, elephantiasis, phrenitis, varicoceles, haemorrhoids, and various mental disorders.[13] Erasistratus is said to have been sceptical about the value of speculating about the theory of humours. He refused to write anything about the origin of the humours, though he did not deny outright that the humours were unimportant as pathogenic substances.[14] But, so far as is known, he did not offer an alternative aetiology of cancer.

Stories about Cancer Patients

One of the lengthiest accounts of a patient suffering from cancer is given by the historian Memnon. Almost nothing is known about Memnon, not even where he lived and when he wrote.[15] According to Memnon, Satyrus, a tyrant of Heracleia, a city on the coast of the Black Sea in Asia Minor, who lived in the 4th century BC, suffered from a cancer of the groin in old age, and the disease eventually killed him:

This man, while still living and oppressed by old age, entrusted his rule to Timotheus, the elder of his nephews. After a short time he became afflicted by an incurable and most painful disease – for a cancer (karkinōma) which had developed between his groin and his scrotum advanced the spreading ulcer quite painfully towards his innards; from out of the open flesh flowed seropurulent discharges, sending forth an offensive and insufferable odour, so that neither his retinue nor his doctors could any longer endure the foul and intolerable smell of the putrefaction. Continuous and piercing pains racked his entire body; because of these he was subject to both sleeplessness and convulsions, until the spread of the disease advanced as far as the inward parts themselves and deprived him of his life. As he was dying, just as also Clearchus had, he caused the onlookers to reflect that satisfaction was being demanded for the cruel and lawless treatment they had inflicted upon their citizens. For they say that although he often prayed earnestly that death would come upon him in his illness, he did not gain his request but was consumed for many days by his bitter and oppressive illness and in this way paid in full what was due. He lived for sixty-five years and for seven of these he was tyrant.[16]

Unlike other stories about patients suffering from cancer, this one depicts the cancer sufferer as deserving of his suffering, owing to the crimes he perpetrated against his subjects during his reign as tyrant. The disease is portrayed as a form of justice meted out to the tyrant.

Already in this early period there are records made by doctors about various different kinds of cancer they encountered. In the fifth book of the Epidemics, a medical work from probably the middle of the 4th century BC, there is mention of an unnamed woman from Abdera, a city in Thrace, who suffered from cancer of the chest and died from the disease: “a woman in Abdera had cancer (karkinos) on the chest and through her nipple a bloody serum flowed out. When the flow was interrupted, she died.”[17] In the seventh book of the Epidemics, which also dates to the same period, there is mention of a man suffering from throat cancer, and the physician claims to have cured him: “the one whose cancer (karkinōma) in the pharanx was cauterized was cured by me.”[18]

An early account of breast cancer appears in Diseases of Women, a medical work which probably belongs to the late 5th or early 4th century BC. The unknown physician writes as follows:

In the breasts hard growths form, some quite large and others not so large: these do not expel pus, but they remain very hard, and out of them hidden cancers (karkinoi) develop. As these cancers are developing, patients first have a bitter taste in their mouths, and everything they eat seems to be bitter; if someone gives them very much to eat they refuse it. They do rude things, they become deranged in their mind, their eyes become hard, and their vision is unclear. Pains shoot up from their breasts to their throats, and around their shoulder blades; they suffer thirst, and their nipples become parched. Such patients become thin through their whole body, and their nostrils are dry, blocked, and contracted. Breathing decreases, the sense of smell is lost, and although there is no pain in their ears, sometimes a stone forms there. Now when this stage has been reached, sufferers are unable to regain their health, but perish from these conditions. If a woman is treated before she has gone so far, her menses will be released, and she will recover.[19]

The author is speaking generally, from wide experience of the symptoms described. The view that a bitter taste in the mouth is a sign of a developing cancer is found elsewhere in medical works of this period: in the second book of the Epidemics, written around 400 BC, the physician comments that “when a cancer (karkinos) has developed, the mouth becomes bitter.”[20] Certain physicians also seem to have held the view that cancer does not arise before puberty unless it is congenital.[21]

In later periods of Greco-Roman history, cancer patients are the focus of some interesting and dramatic stories. According to Dio Cassius, a historian of the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, Julia Domna, the wife of the emperor Septimius Severus and mother of the emperor Caracalla, had breast cancer. When Caracalla was killed by Macrinus in AD 217, Julia was distraught. Macrinus sent her the ashes of her son, and also gave her some instructions:

When he ordered her to leave Antioch as soon as possible and go whithersoever she wished, and she heard, moreover, what was said in Rome about her son, she no longer cared to live, but hastened her death by refusing food, though one might say that she was already in a dying condition by reason of the cancer (karkinos) of the breast that she had had for a very long time; it had, however, been quiescent until, on the occasion referred to, she had inflamed it by the blow with which she had smitten her breast on hearing of her son’s death. And so this woman, sprung from the people and raised to a high station, who had lived during her husband’s reign in great unhappiness because of Plautianus, who had beheld her younger son slain in her own bosom and had always from first to last borne ill will toward her elder son while he lived, and finally had received such tidings of his assassination, fell from power during her lifetime and thereupon destroyed herself. Hence no one could, in the light of her career, regard as happy each and all who attain great power, unless some genuine and unalloyed pleasure in life and unmixed and lasting good fortune is theirs. This, then, was the fate of Julia. Her body was brought to Rome and placed in the tomb of Gaius and Lucius.[22]

It is evident from this story that Julia’s cancer had been carefully managed: a few blows on the breast were enough to inflame it and quickly bring about her death. Julia was unfortunate in life, and unfortunate in death, but others chose to end their lives before this disease killed them.

In one of his letters, Pliny the Younger (AD c.61–112) reports hearing that the poet Silius Italicus, who was suffering from what seems to have been a cancerous tumour, decided to commit suicide to escape the disease at the age of 76 in around AD 102 or 103:

The news has just come that Silius Italicus has starved himself to death in his house near Naples. Ill-health was the reason, for he had developed an incurable tumour which wore him down until he formed the fixed resolve to escape by dying; though he had been fortunate in life and enjoyed happiness up to the end of his days, apart from the loss of the younger of his two sons. The elder and more gifted he left well established in his career and already of consular rank.[23]

Not all stories have a miserable outcome. Saint Augustine, writing in the early 5th century AD, gives the story of an aristocratic lady who recovered from the disease:

In the city of Carthage lived Innocentia, a very devout woman who was descended from the best families of the city. She had a cancer (cancrum)[24] of the breast, a thing which doctors say cannot be cured by any kind of treatment. Hence, the practice is either to operate and remove the affected part from the body, or to omit all treatment, as Hippocrates is said to advise. Thus the patient will live somewhat longer, but death, though delayed, is sure to come of it. She had been told this by a skilled doctor well known to her household, and had turned to God alone in prayer. As Easter approached she was told in a dream to watch at the baptistery on the women’s side, and see that the first woman who came towards her newly baptized made the sign of the cross over the place. She did so, and healing immediately followed. The doctor who had told her to attempt no treatment, if she wished to prolong her life, examined her afterwards and found her entirely cured. It was by a similar examination that he had learned that she had the disease. So he eagerly asked her what remedy she had used, desiring, as far as can be discovered, to know a treatment by which the precept of Hippocrates might be overthrown. When she told him what had happened he answered with a tone and look that seemed scornful, so that she was afraid he might utter some blasphemous word against Christ. But with scrupulous politeness he is reported to have said: “I supposed that you were going to tell me some great thing.” She was already horrified at what he said, but he went on: “How is it a mighty work for Christ to heal a cancer, when he once brought to life a man who was dead four days? [25]

Whether it was luck or a miracle that cured Innocentia, nobody will ever know. The doctor’s scepticism was not unjustified, though an aristocratic lady such as Innocentia surely would not have expected to be rebuked with sarcasm.

The story about Innocentia is not unique: in many Christian accounts, cancer is said to have been healed by a miracle. In the Life of Saint Athanasius the Athonite (10th/11th century AD), for instance, there is mention of a monk called Theodorus who was suffering from the disease:

It would not be right to pass over the story of the monk Theodorus. When he was afflicted with the disease called cancer, it caused him severe and unbearable pain and made him despondent, since all the doctors who saw him had no hope of a cure.

Theodorus asked to be treated by the physician of the monastery, Timotheus; but when Timotheus saw that the disease was cancer, he became dejected. Nonetheless, “for many days he tackled the disease in all sorts of ways, but it remained incurable. For what disease besides cancer does not get better in a short time?” Like Innocentia, Theodorus was eventually cured by miraculous intervention.[26]

The Treatment of Cancer

Greco-Roman doctors recommended various drugs for the alleviation of the pains caused by external cancers. For unulcerated cancers, to help with paroxysms, there is mention of the use of concoctions of rose, melilot, and poppy seed, and similar things; for ulcerated cancers, there is mention of the use of emollients containing litharge (lead monoxide), pig lard, white wax, oil, egg yolks, and other such things.[27]

Some cancers were thought to be curable, but most were regarded as incurable. Aëtius of Amida, a physician writing in the 6th century AD, divided cancers into the curable (euiata) and incurable (aniata). He says that cancers of the head, neck, back, armpit, and groin are incurable: the patient dies of haemorrhaging if these cancers reach the stage where surgery is necessary. He regards cancers of the tip of the breast as curable by surgery.[28]

It was believed that cancers could be cured at their early stages using medications. Galen, for instance, says that medications can make incipient cancers disappear when used in combination with purgatives, and that the same treatment can prevent more advanced cancers from continuing to grow. However, he also states that surgery may be necessary if this does not work.[29]

What sorts of medications were these? Some cancer drugs were derived from plants: for example, from cucumber, the narcissus bulb, castor bean, bitter vetch or horse bean, and cabbage, and many others. Many of these were thought to have antitumoral properties; they were not necessarily regarded as what we might call ‘cures’ but rather as remedies that might slow down or stop the growth of a tumour. Other drugs were derived from animals: for example, for carcinomata, the ash of sea crab burnt with lead, or, for cancers of the woman’s genitals, a female crab crushed up with flower of salt (salis flos) after a full moon and applied in water. Metals like arsenic were also used.[30]

Surgical treatment of cancers was only possible in certain cases. It tended to be avoided because, very often, it caused patients to die sooner than they would have if they continued to struggle with the disease. Stephanus of Athens (7th century AD) says that it is better to strike at the cause of the disease, by attempting to get rid of it using medications, rather than surgical removal. In his view, surgery was most likely to bring about the patient’s death rapidly. He comments on the grim experience of a surgeon, cutting away one cancerous bit of flesh, only to find many tangled new layers of cancerous flesh beneath it:

if you want to use the knife, you will first cut away the veins that are intertwined with each other; then, because the adjoining veins underneath are also affected by the disease, you will have to cut away those as well, and thereupon the ones underneath these also. In short, as the disease has spread in depth and in breadth, the patient dies of the surgery.[31]

In other ancient writings there are instructions for how to operate a cancer: first purge the patient’s black bile, then cut away the tumour, then make sure no root of it is left, then squeeze the surrounding veins to force out the thick black cancerous blood, and then, once all this is done, cauterize the wound.[32] It was, however, recognised that even after excision of the tumour by surgery, the cancer could return and kill the patient.[33]

Breast cancer was a form of cancer often encountered by Greco-Roman doctors and was, as noted above, one of those thought to be curable by surgery. They thought that the reason why women so often get breast cancers – as well as cancers of the uterus or cervix – is that they have more black bile than men.[34] There are some vivid accounts of the surgery of breast cancers.

Leonidas, a doctor working probably in the 2nd or 3rd century AD, says that his operation of a breast cancer patient went as follows. First, the patient was positioned lying down on her back on the operating table. Then, when the appropriate preparations had been made, he made an incision into the breast directly above the cancer and immediately cauterised the wound. When the bleeding from this incision stopped and a scab appeared, Leonidas then made a new, deep incision into the breast, and proceeded slowly, cutting and cauterising, each time waiting for the bleeding to stop before making a fresh incision. This slow method of surgery was designed to avoid hermorrhaging. Once the relevant part of the breast had been cut off, Leonidas then burned the whole area until it was dry.[35]

One of the difficulties that was faced by ancient doctors trying to help cancer patients was that patients often failed to reveal their problems in a timely manner. Because of their fear of revealing to others the medical problems they had in sensitive parts of the body, these patients sometimes left treatment too late for, or did not get treatment at all. Plutarch (AD c.50–120) comments in exasperation about how some people died of an abscess of the anus or of cancer of the womb solely because they did not wish to reveal those parts to physicians:

So painful for all of us is the revelation of our own troubles that many die rather than reveal to physicians some hidden malady. Just imagine Herophilus or Erasistratus or Asclepius himself, when he was a mortal man, carrying about their drugs and instruments, calling at one house after another, and inquiring whether a man had an abscess in the anus or a woman a cancer in the womb. And yet the inquisitiveness of this profession is a salutary thing. Yet everyone, I imagine, would have driven such a man away, because he does not wait to be sent for, but comes unsummoned to investigate others’ infirmities.[36]

Of course, if the patient did ask for treatment for cancer, that course of treatment was incredibly difficult and dangerous to undertake, especially if surgery was required.

Past and Present

In two vivid and sinister lines, the Roman poet Ovid, writing at the dawn of the first millennium AD, described the spread of a cancer within the body:

malum late solet immedicabile cancer

serpere et inlaesas vitiatis addere partes

An incurable cancer spreads its evil roots ever more widely and involves sound with infected parts.[37]

Because of their inability to discover the causes of cancer and the inadequacy of the theory of humours and the limitations of their scientific knowledge, Greco-Roman doctors had little hope of finding treatments for cancer, let alone cures. In spite of the claims of some doctors to have been able to cure it with medications, the disease was still regarded by most ancient doctors as incurable once it had gone beyond its incipient stage, and surgery at later stages usually killed the patient.

The awareness that cancer is created by faulty cell division lay many centuries in the future, as did the realisation that certain external aspects of life, such as what we put into our bodies or what environments we live in, can have an impact on whether or not we get cancer. There was not yet a study such as Richard Doll’s. None the less, the doctors living in these ancient times did their very best to try to understand the disease and help those of our species who were unluck enough to suffer from it.

Konstantine Panegyres is a research fellow at the University of Melbourne, Australia. He completed his DPhil in Classical Languages and Literature at the University of Oxford in 2022. The main focus of his work is on health in the Greco-Roman world and on the editing of unpublished papyri. He is currently working on a book about cancer in Greco-Roman antiquity.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Paulus, Epitomae medicae 6.45 (tr. Adams). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | R. Peto and V. Beral, “Sir Richard Doll,” Biographical Memoirs of the Fellows of the Royal Society (2010) 63–83, at 66. |

| ⇧3 | Stephanus, In Hippocratis aphorismos commentaria 6.38 = CMG 11.1.3.3, 248–9 (tr. Westerink). |

| ⇧4 | Paulus, Epitomae medicae 4.26 (tr. Adams). |

| ⇧5 | Isidorus, Etymologiae 4.8.1. |

| ⇧6 | Isidorus, Etymologiae 4.8.12. |

| ⇧7 | See generally F. Skoda, “Les métaphores zoomorphiques dans le vocabulaire médical en grec ancien,” in Hediston logodeipnon: Logopédies. Mélanges de philologie et de linguistique grecques offerts à Jean Taillardat (Peeters, Paris, 1988) 221–34. |

| ⇧8 | Galen, De tumoribus praeter naturam 7.705–7 Kühn (tr. Reedy). |

| ⇧9 | De natura hominis 4 (tr. Smith). |

| ⇧10 | Galen, De atra bile 5.117 Kühn (tr. Grant). |

| ⇧11 | Galen, ibid. 5.135. |

| ⇧12 | Galen, ibid. 5.128. |

| ⇧13 | Galen, ibid. 5.133. |

| ⇧14 | For discussion, see K.A. Stewart, Galen’s Theory of Black Bile: Hippocratic Tradition, Manipulation, Innovation (2019) 56. |

| ⇧15 | For a recent discussion about Memnon as a historian and the lack of information about his biography, see D. Dueck, “Memnon of Herakleia on Rome and the Romans,” in T. Bekker-Nielsen (ed.), Rome and the Black Sea Region (Aarhus UP, 2006), 43–61, at 44–50. |

| ⇧16 | FGrHist 434 F1 (tr. Keaveney & Madden). |

| ⇧17 | Epidemiae 5.101 (tr. Smith). |

| ⇧18 | Ibid. 7.111 (tr. Smith). |

| ⇧19 | De morbis mulierum 2.24 (tr. Smith). |

| ⇧20 | Epidemiae 2.6.22b (tr. Smith). |

| ⇧21 | Coacae praecognitiones 502: “The following diseases do not arise before puberty: pneumonia, pleurisy, gout, nephritis, varicosities in the lower leg, a bloody flux, cancer (karkinos) unless it is congenital” (tr. Smith). |

| ⇧22 | Dio Cassius 79.23 (tr. Cary). |

| ⇧23 | Pliny, Epistulae 3.7 (tr. Radice). |

| ⇧24 | Cancrum is the later Latin form of cancer. |

| ⇧25 | Augustine, De civitate Dei 22.8 (tr. Green). |

| ⇧26 | Vita anonyma sancti Athanasii Athonitae (BHG 188) 56 (tr. Greenfield & Talbot). |

| ⇧27 | Aëtius, Iatricorum libri 16.52–3. |

| ⇧28 | Ibid. 16.48. |

| ⇧29 | Galen, De methodo medendi 10.979 Kühn (tr. Johnston & Horsley). |

| ⇧30 | For a lengthy discussion, see V. Bonet, “Guérir du cancer dans l’Antiquité? Quels remèdes?,” in P. Boulhol, F. Gaide & M. Loubet (edd.), Guérisons du corps et de l’âme (2006) 63–77, at 70–4. |

| ⇧31 | Stephanus, In Hippocratis aphorismos commentaria 6.38 = CMG 11.1.3.3, p.251 (tr. Westerink). |

| ⇧32 | Paulus, Epitomae medicae 6.45. |

| ⇧33 | Celsus, De medicina 5.28. |

| ⇧34 | Paulus, Epitomae medicae 4.26. |

| ⇧35 | Aëtius, Libri medicinales 16.45. |

| ⇧36 | Plutarch, Moralia 518D (tr. Helmbold). |

| ⇧37 | Ovid, Metamorphoses 2.825–6 (tr. Miller). |