Alan Cardew

A thousand years scarce serve to form a state;

An hour may lay it in the dust: and when

Can man its shatter’d splendour renovate,

Recall its virtues back, and vanquish Time and Fate.

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto LXXXIV, 796–80

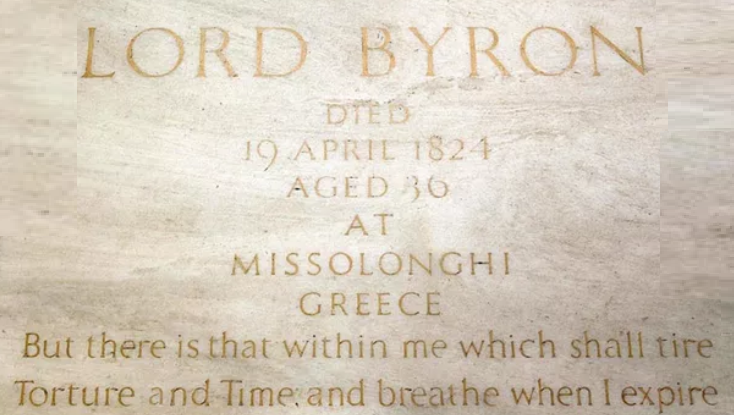

Last month saw two very different ceremonies to mark the 200th Anniversary of the death of Lord Byron. In London, a wreath was laid by Lord Lytton with a group of members of the Byron Society on the simple grey slab which commemorates Byron in ‘Poets’ Corner’ in Westminster Abbey. In Athens, on National Byron Day he was remembered as a hero with the Minister of Defence, Nikos Dendias, giving an address to members of the Hellenic Armed Forces at the Hellenic Army Academy. In Athens, there were nineteen-cannon salutes to mark 19 April, the date of Byron’s death. One celebration subdued, the other martial.

In the Greek capital, there is a statue of Byron in the arms of Hellas near the Greek Parliament, in a place of honour near the entrance of the National Gardens.

Westminster Abbey had long resisted any monument to Lord Byron. The Church of England has always put its entire faith into respectability (however it is currently defined) and Byron was considered far too scandalous a figure to admit into its shrine of British worthies. From the start the Church refused to inter Byron in the Abbey due to his “questionable morality”, then in 1834 it refused to give space to a statue of the poet by Thorwaldsen; it was only in 1969 that the meagre memorial slab was permitted.

In the National Gallery in Athens a painting of 1861 by Theodoros Vryzakis depicts the reception of Lord Byron. As he lands on the Greek mainland at Missolonghi Byron is greeted as a hero, a poetic Messiah who has come to resurrect Greece, and to rescue it from centuries of tyranny and historical oblivion. His way is strewn with palms and a Bishop blesses his coming – indeed a priest carries an image of the risen Christ. Byron is welcomed by Alexandros Mavrocordatos, a friend who became the first Prime Minister of Greece.

How has the double status of Byron emerged, hero and pariah? Is there a clue to be found in his Classical education? Byron touches on the moral dangers of such an education in Don Juan (1819–24), where Juan’s mother, a very proper lady, worries about the improper influences of such studies.

His classic studies made a little puzzle,

Because of filthy loves of gods and goddesses,

…

Ovid’s a rake, as half his verses show him,

Anacreon’s morals are still a worse sample,

Catullus scarcely has a decent poem,

I don’t think Sappho’s ode a good example,

Although Longinus tells us there is no hymn

Where the sublime soars forth on wings more ample,

But Virgil’s songs are pure, except that horrid one

Beginning with Formosum pastor Corydon.

Don Juan I, xvi–xvii

Here Byron satirises the virtuous horror of the then growing moralisers of what he called “the age of cant”, which was gradually replacing an age of scandal; a time of bucks, dandies, and aristocratic extravagance – the Prince Regent, Beau Brummell, Gillray and Rowlandson. An age vanquished, like Lord Byron, by emerging Victorian proprieties. As with Ovid, Byron was sent into exile for his indecencies, an Emperor’s prohibition being replaced by the voice of outraged public sensibility.

In the last couplet quoted above, Byron alludes to the opening lines of Virgil’s second Eclogue, in which a shepherd burns for the love of the boy Alexis, his master’s pet, o formose puer (“o beautiful boy”). Byron had made a similar allusion, on this occasion drawn from Petronius, when hinting in a letter at his own ambiguous amorous encounters on his first visit to Athens in August 1810; when he was busy “conjugating the verb ἀσπάζω [=to embrace]”. Byron may still be too polymorphously perverse even to fit within the fluid boundaries of contemporary sexuality.

At Harrow School Byron was introduced to the varied, rather amoral fare of Classical texts – the epigrammatic, the lyrical, rhetorical, elegiac. Verses were composed in Latin and Greek and Horace was favoured as a model of good sense, Augustan order, and land ownership. Speeches had to be learned, whole passages from Virgil and Homer, and Byron recited the address of King Latinus from Aeneid 11 to great success one Speech Day.

Studying epic poetry was, as it had been in the days before Socrates, seen as the fit preparation for an aristocracy. The stern injunction of Achilles’ tutor Phoenix “always be first and outdo the rest” was as axiomatic to the Homeric nobility as it was to the English. Striving for excellence in all its forms, physical, martial, sartorial, poetic, reflected the ancient agon, the continual striving and competitiveness which Burkhardt identified as being the characteristic of Ancient Greece, its distinguishing feature. Indeed, the lofty figures of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives – Caesar, Alexander, Solon, Themistocles, Mark Antony, the Catos, and even Alcibiades – were, despite their failings, exempla of greatness to be emulated, paralleled, and outdone. The young Byron, possessed of wit, rank, Apollonian beauty, and wealth, seemed chosen by the gods to take up such a challenge.

(Royal Collection, UK).

After leaving school, before or after university, gentlemen often embarked on a Grand Tour of Western European courts – the Hague, Versailles, Venice, and Rome – to acquire polish and courtliness, as well as fine clothes and antiquities; they were often accompanied by a tutor (a futile task). Byron was unusual in conducting his own Grand Tour which ranged much farther than the conventional one, and included Greece and other western domains of the Ottoman Empire.

Byron’s reaction on seeing Athens was a mixture of elation at reaching the antique goal, and disappointment at seeing what the centuries had destroyed and what men were still doing (as in the figure of Lord Elgin) to ruin the ruin of what was left. The Turks did not care about the place and the Greeks proved completely indifferent. What had happened to the Greeks?

Ancient of days! august Athena! where,

Where are thy men of might? thy grand in soul?

Gone – glimmering through the dream of things that were:

First in the races that led to Glory’s goal.

They won, and pass’d away – is this the whole?

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, II, x.

It was impossible to imagine the wonder of what once was there, and to picture what was once there. Musing over the remains of the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, he wrote:

… nor ev’n can Fancy’s eye

Restore what Time hath labour’d to deface.

Yet these proud pillars claim no passing sigh;

Unmov’d the Moslem sits, the light Greek carols by.

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, II, x

J.J. Winckelmann’s judgement in Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1755) that “the only way for us to be great, and, if it is possible, immortal, is through the imitation of the ancients” now seemed more unrealisable than ever. And yet there lingered something of the original in the spirit of the place, in the mountains, isles, forests, sea, and in the light. Byron was overwhelmed by the sanctity of Greece in the manner of an Hellenic Jacob: “How full of awe is this place!”

Where’er we tread is haunted, holy ground;

No earth of thine is lost in vulgar mould,

But one vast realm of wonder spreads around,

And all the Muse’s tales seem truly told.

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, II, lxxxviii

Despite being overcome by spells of gloom and rapture Byron still managed to emulate Greek myth and like Leander swam the Hellespont. He also braved a visit to the murderous Ali Pasha of Ioannina who ruled a large part of north-west Greece or Rumelia. Byron experienced at first hand the tribal complexity of the country, witnessed its cruelties and brigandage, heard of the raids, betrayals, plunders, and massacres. Ali Pasha’s massacre of the garrison and population of Preveza which had reduced its population by thousands was one of many similar incidents, many of which prompted revenge and unspeakable cruelties. Albanian, Greek and Turk were intertwined in a perpetual, low-level civil war of reprisal and revenge.

How to untangle the Greeks and restore their ancient glory? A way was suggested by Thomas Hope, another oriental traveller, whose 1819 novel Anastasius was vastly influential. Published a few years after Byron’s Childe Harold its peripatetic hero similarly explored the Ottoman world. Early in the work Anastasius learns of the Greek diaspora: from mountain tribesman to the remnants of the Byzantine aristocracy (the Phanariotes) living in the heart of Istanbul, to the inhabitants of the isles. What unifies them is the spirit of competitive supremacy:

…was not every commonwealth of ancient Greece as much a prey to cabals and factions as every community of modern Greece? Does not every modern Greek preserve the same desire for supremacy, the same readiness to undermine, by every means fair or foul, his competitors, which was displayed by his ancestors? …. the very difference between the Greeks of time past and of the present day arises only through their thorough resemblance. (Anastasius Vol. 1)

Byron said that he wept when he read Hope’s book, and that he, Byron, would have given some of his best poems to have written it. Perhaps this testament to the continuation of the spirit of the ancient agon gave Byron hope.

Another influential book of the period was Comte de Volney’s The Ruins of Empire: Or a Survey of the Revolutions of Empires (1796). It was translated into English by Thomas Jefferson, and Mary Shelley put it on the reading list for the education of Frankenstein’s creation. In the book, the ruins of Palmyra awaken in the beholder a defiance of tyranny and superstition: “Hail solitary ruins, holy sepulchres and silent walls! you I invoke; to you I address my prayer!” In the tone of its call to freedom and liberty, and its hatred of superstition (monotheism), it is similar to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Hellas, written in 1822 while he was staying with Byron. Greece is reborn on a visionary plain – not only its people but its landscape.

A brighter Hellas rears its mountains

From waves serener far.

Ruins inspire, tyranny and despotism are overthrown, and liberty and love greet a radiant world, with antiquity raised to a higher power.

Another Athens shall arise,

And to remoter time

Bequeath, like sunset to the skies,

The splendour of its prime.

The task of rebuilding Greece was political and metaphysical. Enchantment mixed with lamentation, thoughts of a lost world with dreams of a new one.

In Germany, it was feared that the ideal world of Greece might not come again, a feeling expressed in Friedrich Schiller’s Die Götter Griechenlandes (The Gods of Greece, 1788):

Schöne Welt, wo bist Du?

(Beautiful world, where are you)

Sehnsucht, unappeasable longing for greatness lost forever, also found its place in Friedrich Hölderlin’s 1797–9 novel Hyperion; oder, Der Eremit in Griechenland (Hyperion, or The Hermit in Greece) whose hero has narrowly survived an earlier attempt to win Greek independence in the 1770 Ottoman/Russo War. The task is, and has been, an impossible demand, practical and ideal:

You must go down into the world of mortals like a ray of light, like a shower of refreshing rain; you must illuminate it like Apollo, shake it to its depths and give it a new life like Zeus, otherwise you are not worthy of your heaven.

Hyperion’s failure leads to the death of his love Diotima and to the life of a hermit. Like Shelley’s Hellas the book is written in what has been described as a “monotonously ecstatic tone” and conveys a “devastating glory”. To the Homeric burden has been added the Pindaric.

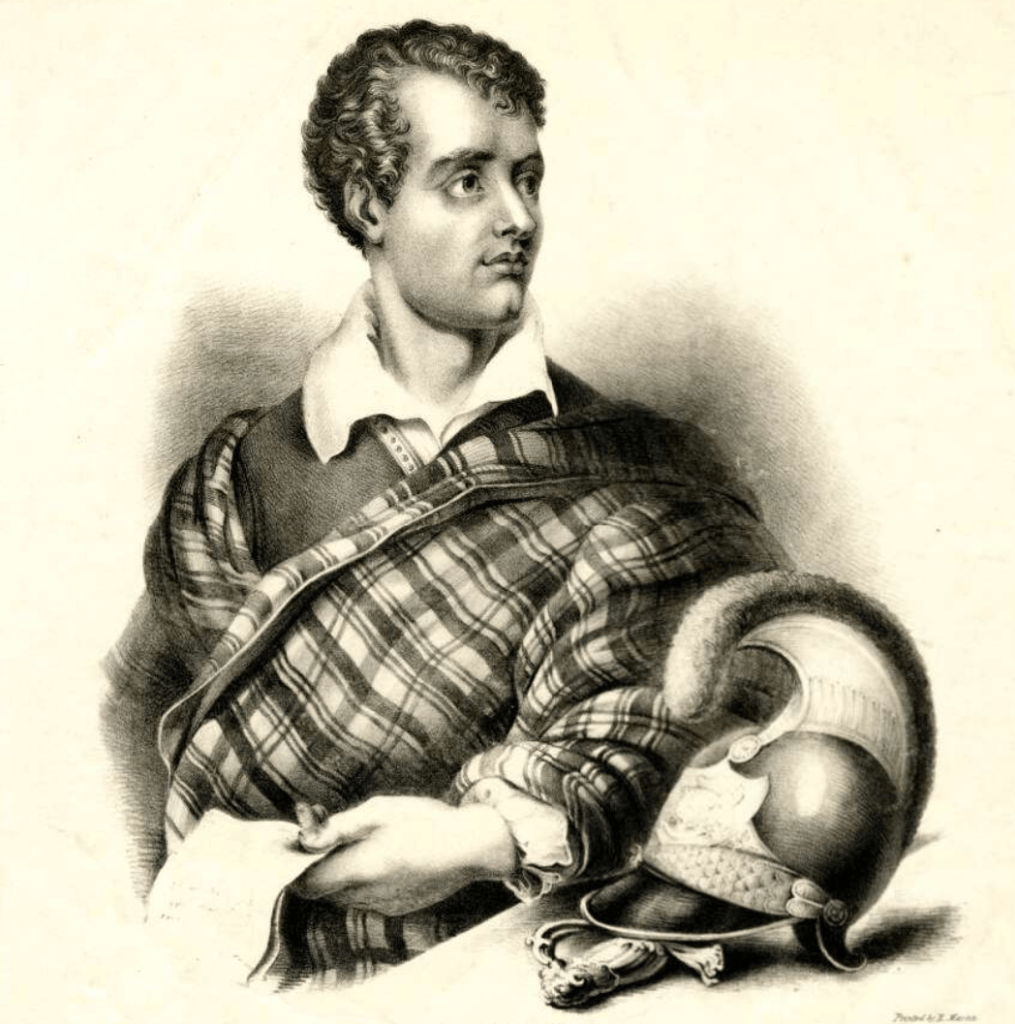

Was Byron the man to bear such a burden? Goethe judged that Byron’s daemonic power to achieve was drawn directly from Nature, from shooting, swimming, riding, sailing, and rowing. Byron had Produktivmachende Kräfte (“productive forces”), and “was one of the most productive men who ever lived”. According to Goethe, Byron’s poetical power eclipsed all other mortals, and he was not held back by petty morality, being possessed of a virtue of which the bourgeoisie had no conception. Aristocratic, handsome, he perfectly fulfilled his mission; he was neither antique nor romantic but the present day itself. He could overcome melancholy and vaporous yearning, for Byron embodied the Greek ideal. It would seem he was the efficient cause of Providence.

Adam Mickiewicz grasped Byron’s historical mission, and translated Byron’s The Giaour: A Fragment of a Turkish Tale (1813) which followed Childe Harold and was also a remarkable success, selling 10,000 copies on the first day. It is an allegory of the war over Greece (Leila) Turkey and Russia of 1770. It begins with a description of the tomb of Themistocles, overlooking the Piraeus:

No breath of air to break the wave

That rolls below the Athenian’s grave,

That tomb which, gleaming o’er the cliff,

First greets the homeward-veering skiff,

High o’er the land he saved in vain:

When shall such a hero live again?

Despite these initial doubts over heroic destiny the poem breathes fire and defiance, and Mickiewicz, catching this fire, was particularly taken with the couplet:

For Freedom’s battle once begun

Bequeathed by bleeding Sire to Son.

In his 1822 Preface to the poem, Mickiewicz noted the universal importance of Lord Byron, and the latter’s superhuman concerns:

He had always had before his eyes the great problems of the world, the problems of the fate of the human race and of the future life. He had tackled all the basic moral and philosophic questions, he had coped with all the cruxes and difficulties of dogmas and traditions, he had cursed and fumed like Prometheus, the Titan, whose shade he loved to evoke so often.

Mickiewicz also appreciated Byron’s humour and irony, which stemmed not merely from the sorry contrast between the modern and the antique. The mock-heroic was more than a cynical refuge from dismay at the failure of the present to live up to the past. It was not simply for latter-day epigoni but was a classical staple – satire with tremendous assurance. The form had been burnished by Byron’s favourite poet Alexander Pope, and both Pope and Byron were heavily influenced by Horace and Juvenal, as is shown by Byron’s early Hints from Horace and Pope’s Imitations of Horace.

Byron’s expedition to mainland Greece in the late winter of 1823/4 was equipped with a library of books – Montesquieu, Voltaire, La Rochefoucauld – two barrels of cash which funded the Greek Navy, medical supplies for 1,000 men for two years, and served to feed the importunacies of a large band of Suliote warriors – all at Byron’s expense. Thousands of pounds served to pay for a lot of patriotism; indeed, Byron’s main contribution to the cause was as much financial as spiritual, since he did not get the chance to fight.

Byron arrived with a clutch of domestic servants who included his doctor, valet and cook, a small menagerie, his dog and horses, and a motley crew of hangers-on, assorted Philhellenes, a printing press, and cannons. For the occasion of his arrival Byron had designed a plumed helmet for himself. It was vaguely Hoplite, but intended as a cavalry helmet which he based on descriptions of armour in Homer. Black and gold, the helmet was decorated with Byron’s coat of arms and his motto Crede Byron (Trust Byron). To set it off Byron sported a Highland plaid. He wore both helmet and cloak when drilling his band of Suliot brigands, who, on the whole, rather despised the notions of the phalanx and the Waterloo square.

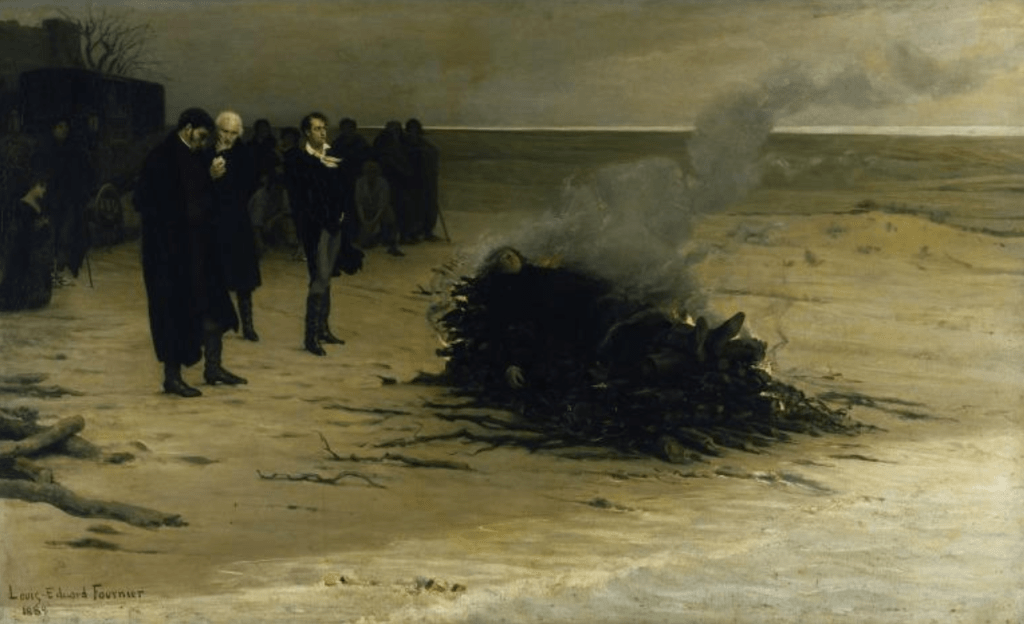

Byron’s death is often seen as a failure, at worst a sad waste; at best a vainglorious effort petering out in the mire of Missolonghi, the hero succumbing to fever, bled to death by his doctors. The marshes of Missolonghi with their constant winter rain was certainly far from the ideal landscape for a Byronic hero… and Byron was said to draw power from Nature.

It was certainly not the ideal landscape that the taciturn Conrad, half-pirate and half-philosopher, enjoyed in Byron’s The Corsair, fighting the Turks from his tower on the island of Delos, the favoured isle of Apollo. Supported by the beauty of the Cyclades, he could rise to any challenge, brave any danger, and so “snatch the life of life”.

Slow sinks, more lovely ere his race be run,

Along Morea’s hills the setting sun;

Not, as in Northern climes, obscurely bright,

But one unclouded blaze of living light.

But in the sunless rainswept mud of Missolonghi Byron had no such sustenance. His resemblance to the ideal, the Belvedere Apollo was fading. Grey hairs and a tendency to fat led him to an almost anorexic diet that greatly weakened him. Cutting a fine figure was essential to his leadership, and demanded by the ancient precepts of καλοκαγαθία (kalokāgathiā), beautiful goodness. The Promethean task of securing the destiny of Hellas required that he create some order out of the chaotic mess that enmired the Greek cause in Missolonghi – factionalism , rivalries, betrayals, alarms, mutinies, shootings, contending plans of action, disappointments of every kind. This was the true battle.

In January 1824 Byron still had hopes for Greece which he expressed in a short poem on his 36th birthday.

The Sword, the Banner, and the Field,

Glory and Greece around us see!

The Spartan borne upon his shield

Was not more free!

Awake (not Greece – she is awake!)

Awake, my Spirit! think through whom

Thy life-blood tracks its parent lake

And then strike home!

He enlivened the Hellenic cause but gradually his energy was sapped by the dreary clime of Missolonghi, and the bickering and disputes that engulfed him.

“INTENSITY,” William Hazlitt wrote, was “the great and prominent distinction of Lord Byron’s writings,” and perhaps it was intensity in life, in his Greek adventure, that proved fatal. He was tied to the Greek cause as his own hero Mazeppa was tied to a galloping horse; it could only lead to exhaustion. The upshot of it all was that, in early April, Byron experienced a syncope, fainting and a fit. His doctors applied the leeches. Overwhelmed by the superhuman demands put upon him, he began to decline; some days later he was dead. A life destroyed by too much life.

A fitting Greek epitaph for Byron would be Aristotle’s to Hermias; a testimony of a death brought about in pursuit of virtue and excellence, ἀρετή (aretē):

VIRTUE toilsome to mortal race

Fairest prize in life,

Even to die for thy shape,

Maiden, is an envied fate in Hellas

& to endure vehement, unceasing labour

Such fruit do you bestow on the spirit

Like to the immortals, and better than gold.

A contempory epitaph is best found in the words of a simple Suliot song discovered by James Notoupolos. All was not in vain:

Missolonghi groaned and the Suliots cried

For Lord Byron who came from London.

He gathered the klephts and made them into an army

The klephts gave to Byron the name of father

Because he loved the klephts of Rumele…

The woodlands weep, and the trees weep

The castle of Missolonghi groans,

Because Byron lies dead at Missolonghi.

Alan Cardew was Director of the Humanities at Essex University. He now is an active member of the Centre for the Study of Platonism at Cambridge. He is a Fellow of the Foro di Studi Avanzati in Rome and a Fellow of the Athens Institute for Education and Research. He has published on Nietzsche, Jung, Cassirer, Freud, Heidegger, and Hölderlin, and claims a tenuous family connection to Lord Byron.

Further Reading

Countess Marguerite Blessington, Conversations of Lord Byron with the Countess of Blessington (London, 1834).

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron of Rochdale, The Works of Lord Byron (T. Moore ed., 17 vols, London, 1833).

David Howarth, The Greek Adventure: Lord Byron and Other Eccentrics in the War of Independence (Collins, London, 1976).

Leslie Marchand, A Portrait of Byron (John Murray, London, 1971).

Mark Mazower, The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Europe (Allen Lane, London, 2021).

Stephen Minta, On a Voiceless Shore: Byron in Greece (Henry Holt, New York, 1998).