Edmund Stewart

How many ancient Spartans can you name? On the TV show Pointless, contestants are challenged to come up with a name in a given category that no one in a focus group of 100 people could remember (a “Pointless” answer). The show has never, to my knowledge, asked about Spartans.

I suspect that Leonidas, the hero of Thermopylae, would score over 80. Cleomenes I, his mad and bad predecessor, might perhaps be remembered by 10 to 20, as might Lysander, the victor of the Peloponnesian Wars (431–404 BC). But how many would remember Agesilaus? Whatever the answer, it is probably far fewer than he deserves.

According to the 4th-century historian Theopompus, Agesilaus was “the greatest and most brilliant of any living at that time”. Yet, strangely enough, he was not one seemingly born for greatness or one from whom much was expected for many years. He was the younger son of King Archidamus II of Sparta (d. 427/6 BC) by his second wife.

The Spartans had two royal houses: rather than a monarchy, it was a dyarchy. The myth is that two twins, Procles and Eurysthenes, were born at the same time but no one knew which was the elder. The Spartans accepted them both, and their descendants, as kings. Archidamus was the Eurypontid king (that is he was a descendent of Procles) and ruled during the outbreak of the first phase of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta (431 to 421 BC, commonly called the Archidamian War as a result).

As a young man, Agesilaus grew up under the shadow of his elder half-brother, Agis II, the senior king throughout much of the Peloponnesian War. He underwent the training regime of the agōgē along with other Spartan citizens and was treated very much as a private person. Up until the time of Agis’ death, Agesilaus had done nothing notable and held no senior command – as far as we know. He was already in his forties… but soon all Greece would be at his feet.

We often tend to idolise youth and think of the great men of history as people who, like Alexander, were precocious in their talents, who lived fast and died young. But it turns out that even those in middle age, or old age, can still be called to greatness. This was particularly true among the Greeks. In most Greek states no one younger than thirty was eligible for public office. In Sparta, the senate, or Gerousia, was composed entirely of old men over the age of sixty (with the addition, that is, of the two kings).[1]

On the battlefield, the Greeks valued old-timers for their experience and steadiness: they were marshalled behind the more vigorous but potentially more flighty younger men. Spartan citizens were liable to serve for forty years after coming of age as hoplites. Agesilaus was still on campaign in his eighties. This does not mean that he was in a bunker somewhere staring at a map. It means he was out in the field, wearing a full panoply, and running into battle. Fame among the Greeks, for whom the average life expectancy wasn’t more than thirty years, often came as a result of longevity. Agesilaus would dominate Sparta in part by simply outliving four of his Agiad royal colleagues.

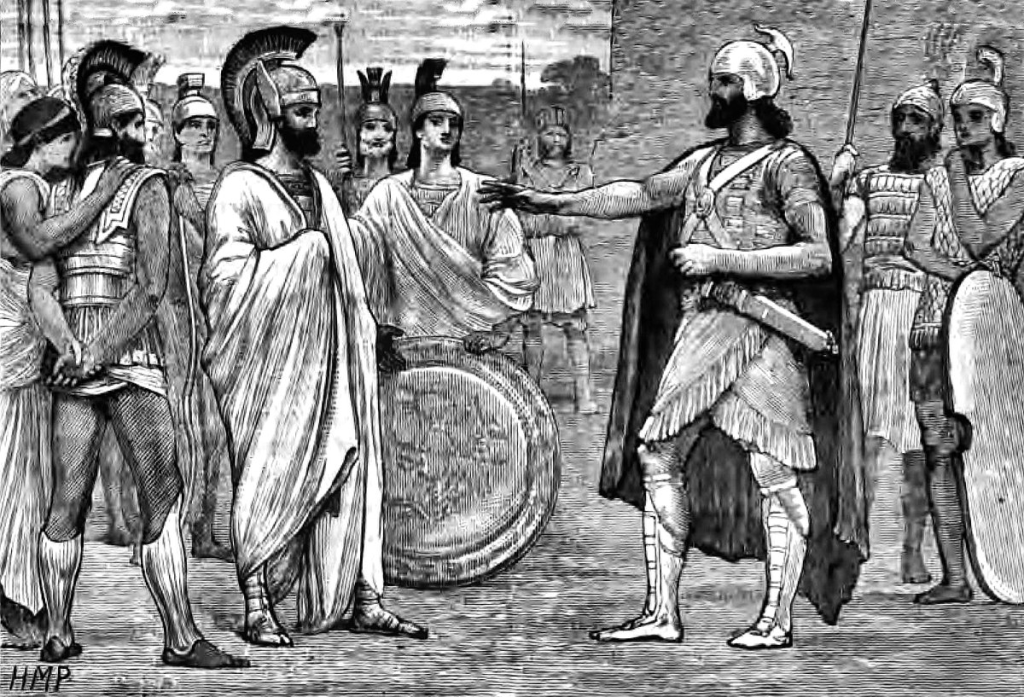

In 400 BC Agesilaus grabbed his chance at greatness. The rightful heir to the Eurypontid throne was the putative son of Agis, Leotychidas. But there were rumours that Leotychidas was in fact the illegitimate child of the Athenian general Alcibiades, who had unwisely had an affair with Agis’ wife during his period of exile in Sparta. Agesilaus had the support of the admiral Lysander, hero of Aegospotami, the battle in 405 which finally ended the three-decades long Peloponnesian War. This decided the succession debate in Agesilaus’ favour. Lysander hoped that if he could place his friend Agesilaus in power he would have a malleable king whom he could dominate. In that he was to be much mistaken.

Agesilaus would prove a general of exceptional ability, as well as a forceful diplomat. In 400 BC Sparta was already the most powerful Greek city, thanks to its victory over Athens. In 396, rumours circulated that the Persian King Artaxerxes was looking to challenge his former ally. Lysander was eager to return to the coast of Asia Minor, where he had enjoyed such success and where he had placed his friends as tyrants in the Greek cities.

He persuaded Agesilaus to ask the committee of five ephors (effectively the executive of the Spartan state) for an army of 8,000 allies and emancipated Helots, to which were added thirty Spartan citizens to act as a council of advisors. Once on the ground in Ephesus, Agesilaus asserted his authority over the over-mighty Lysander and won a string of victories against the Persians, and especially the governor of Sardis Tissaphernes. The Great King lost patience with his minion and had him executed for his failures.

In 395 the Spartans recognised Agesilaus’ achievement with the exceptional honour of command both by land and sea. But not all would fare well in naval matters, in which the Spartans were comparative amateurs. In the following year, a Persian fleet commanded by an Athenian by the name of Conon dealt a crushing blow to Laconian naval supremacy at the battle of Cnidus. Worse still, the cities of the Greek mainland rose in rebellion against Spartan hegemony. Athens was back, a mere eight years after her walls were demolished, her democracy overthrown and her allies had revolted. Sparta’s former allies Thebes and Corinth were now enemies. Lysander was killed fighting at Haliartus in Boeotia. Agesilaus’ Agiad colleague Pausanias was blamed for Lysander’s death and driven into exile.

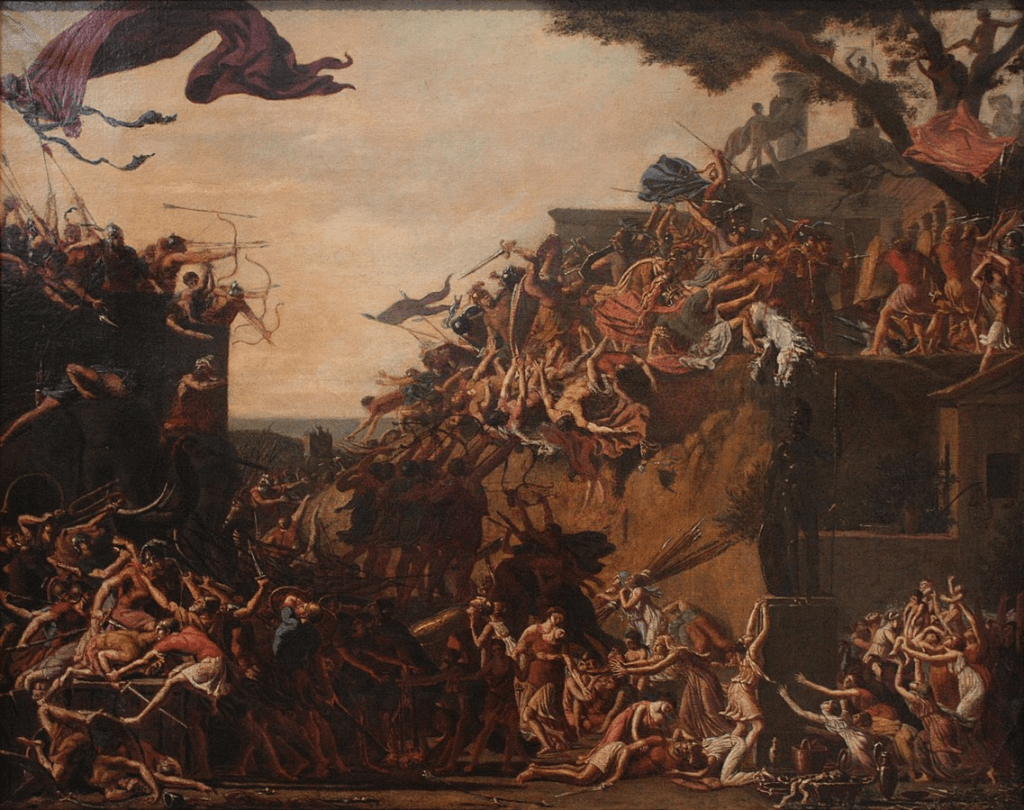

In desperation, the ephors recalled Agesilaus from Asia. He marched into Greece by land, the way Xerxes and the Persians had come in 480. Despite the mass of enemies ranged against him, his advance proved unstoppable. By August, Agesilaus reached the town of Coronea in Boeotia, not far from Thebes. He faced an allied army composed of Thebans, Athenians, Argives, Corinthians, Aenianians, Euboeans and Locrians. The battle that followed was later described as being “unique in our time”.

In Agesilaus’ army was a young Athenian called Xenophon. He had ended up serving the Spartan king as a result of a series of extraordinary wanderings through Asia with the famed Ten Thousand that are altogether another story (Xenophon later recounted his adventures in his Anabasis). Xenophon saw Agesilaus in action as a general first hand and tells us this about his qualities as a leader and trainer of men:

He brought into the field an army not a whit inferior to the enemy’s; he so armed it that it looked one solid mass of bronze and scarlet; he took care to render his men capable of meeting all calls on their endurance; he filled their hearts with confidence that they were able to withstand any and every enemy; he inspired them all with an eager determination to out-do one another in valour; and lastly he filled all with anticipation that many good things would befall them, if only they proved good men. For he believed that men so prepared fight with all their might; nor in point of fact did he deceive himself. (Agesilaus 2.7–8, trans. Merchant and Bowerstock).

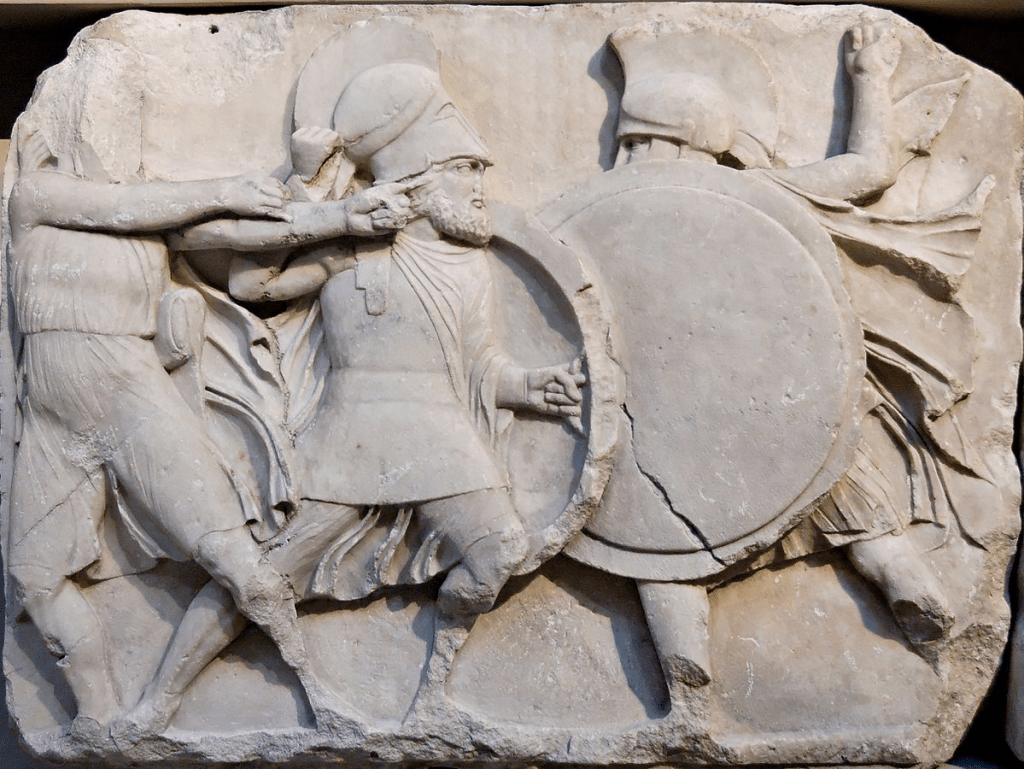

In the fight itself, Agesilaus took the place of honour on the right flank and drove his Argive adversaries before him in flight up Mt Helicon. Then he wheeled his division round to face the Thebans, who had gained some success against Agesilaus’ Orchomenian allies. As Xenophon tells it:

Thrusting shield against shield, they shoved and fought and killed and fell. There was no shouting, nor was there silence, but the strange noise that wrath and battle together will produce. In the end some of the Thebans broke through and reached Helicon, but many fell during the retreat. (2.12)

Agesilaus was victorious, “though wounded in every part of his body with every sort of weapon” (2.13). He and his army passed triumphantly across the Isthmus of Corinth to Sparta.

The war continued for eight more years, despite further successes (notably a victory at Lechaeum, the port of Corinth, where Agesilaus commanded on land and his half-brother Teleutias by sea). The rebellious Greeks were only brought to submission by the intervention, once again, of the Persian king. In 387/6 the grain supply route from the Black Sea was cut and Agesilaus forced the Athenians and Thebans to accept what became known as the King’s Peace, by which the Persians gained back control in Asia, while Sparta remained the hegemon in Greece.

Agesilaus was by now the greatest man in the greatest state in Greece. But it was not to last. In 382, the Spartan general Phoebidas (in a shameful coup that was later backed by Agesilaus) captured the acropolis of Thebes (the Cadmea) and imposed on the Thebans a tyranny. In the winter of 379, a group of Theban exiles launched a daring raid from Athens to restore their ancestral constitution. They stole into the city, murdered the Spartan-backed tyrants in their homes, and called their fellow citizens to arms. It was to be war between Sparta and Thebes from now on.

Agesilaus seems to have nurtured an almost fanatical hatred against the Thebans, which may to some extent have clouded his judgement. He pursued the course of war unrelentingly. The general Antalcidas, on one occasion in which Agesilaus suffered a wound in a fight with the Thebans, remarked that “they are paying you well for teaching them to fight, when they had no desire for it in the first place, and no skill either.”[2] Two ‘students’ of Agesilaus, Epaminondas and Pelopidas, proved exceptionally talented. In 371, they crushed a Spartan army led by the Agiad king Cleombrotus, who died in the battle. It was the worst defeat Sparta ever suffered.

In the following year, the Thebans came to Laconia. It was the first time that an enemy had ever set foot in arms in the Eurotas valley. Sparta was unfortified; its citizens had looked to the strength of their men for protection alone. And in this moment of crisis, the Spartans turned to Agesilaus. He mustered his men by the high ground of the Acropolis above the banks of the Eurotas river. Epaminondas and his troops began to cross the freezing waters, chilled by the melting snows from white-capped Taygetus. Agesilaus stared across at his younger enemy and merely commented, “Oh ambitious man.”

In the end, the Spartans resisted the Thebans successfully and Agesilaus crushed internal unrest among the citizen body. They had survived. But the days of greatness were over. The Spartans lost their allies and their control over the neighbouring Messenians (whom they had enslaved centuries before to work as their chattels). They would never be a leading power again. The Spartan citizen body was already in decline, due to the property qualification for citizenship and a failure to enforce any rule of primogeniture. At the end of the 3rd century BC, Sparta would fall into a destructive pattern of social unrest, revolution and tyranny.

But Agesilaus would have one final moment of glory. Sparta needed money, and that money would increasingly have to come from mercenary service. Fighting men were Sparta’s greatest asset and now her biggest export. Agesilaus went to work for the rebel king of Egypt. He was more than eighty years’ old but had lost none of his vigour. After several adventures and victories, he left Egypt loaded down with 230 talents of silver. Although that cargo returned home safely, Agesilaus himself died off the Libyan coast, only to return to Sparta embalmed in wax.

Edmund Stewart is Assistant Professor in Ancient Greek History at the University of Nottingham. He has previously written for Antigone on how to build a Greek temple, and his other essays can be found here, here, here, here, here, and here.

Further Reading

The University of Nottingham’s Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies gives further information about Sparta and our research. You may also like to join our free online series of talks on Spartan history, Sparta Live. For a wide ranging study of Agesilaus’ life and times, see Paul Cartledge’s Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta (Duckworth, London, 1987).