Jesse Russell

“I am a popularizer, not a scholar.”

“For Athens, truly the mother of beauty and of thought, is also the mother of freedom. Freedom was a Greek discovery. The Greeks were the first free nation in the world.”

In a certain sense, Classics has always been politicized. The Romans attempted to make Greek culture their own, and medieval figures likewise appropriated Roman culture for their own political projects. It is thus no surprise, in our world, that there is a contentious struggle over the place of Classics in the school (K-12) and university curricula. Rightly or wrongly, Classics is routinely associated with conservative – and sometimes even extreme right-wing – political movements.

One of the architects of contemporary left-wing thought, Karl Popper (1902–94), famously described Plato’s writings as “purely totalitarian” in his 1945 work, The Open Society and Its Enemies. Other Classicists have viewed the Classical tradition as one that is misappropriated by imperialists and racists. In recent years, scholars such as Dan-el Padilla Peralta have attempted to distance Classics from “whiteness”. Although not (quite) as charged with racial angst, there was a similar tug-of war over the meaning of Classics in the 20th century. At the center of this debate was American Classicist Edith Hamilton (1867–1963).

Hamilton is best known for her 1942 work, Mythology, which still serves as a useful introduction to Classical culture in high schools and universities throughout America. However, she also attempted to communicate the relevance of Ancient Greek culture to 20th-century Americans laboring against the totalitarian systems of fascism and communism (both of which attempted to use Classics for ideological purposes).

Hamilton saw the Greeks as a fundamentally rational people, and viewed Classical Athens as a period where academic, artistic, and political freedom flourished, and the notion of the individual was discovered. She was also a Christian – if an unorthodox one – who saw parallels between Christianity and the works of Plato. The emphasis in Hamilton’s reading of both Plato and Christ was upon freedom and individualism.

Hamilton was thus an “Old Liberal” or “Classical Liberal”, who prized freedom above what in the 1990s would be called “political correctness”, or what in the 2020s would be referred to as “wokeness”. But this does not mean she was a conservative – especially by the standards of her day. She was a suffragist, and opposed fascism. She supported the League of Nations (1920–46, forerunner to the United Nations), was an opponent of nuclear weapons, and advocated against racial injustice: she spoke out when the African-American farmhand Jimmy Wilson was sentenced to death in 1958 for the alleged violent robbery of an elderly woman (the fact that he only stole $1.95 stirred up widescale international ire towards the United States during the Cold War).

Hamilton was not only an author of Classically-focused books. In 1936, she wrote The Prophets of Israel to emphasize the contribution of Ancient Hebrew thought to the formation of the Western mind, and as a riposte to Nazi attempts to eliminate Hebrew thought and culture from the Western tradition.

Born in Dresden, Germany in 1867, Hamilton moved immediately to the United States, and went on to receive her bachelor’s degree from Bryn Mawr College in 1894. After a brief but disappointing attempt to study in Germany, she went on to serve as headmistress of Bryn Mawr Preparatory School from 1896 to 1922. She did not have the PhD credential of many professional Classicists. Instead, she was first and foremost a popularizer, celebrating the Greeks for their vitality, over the more “artificial” Romans.

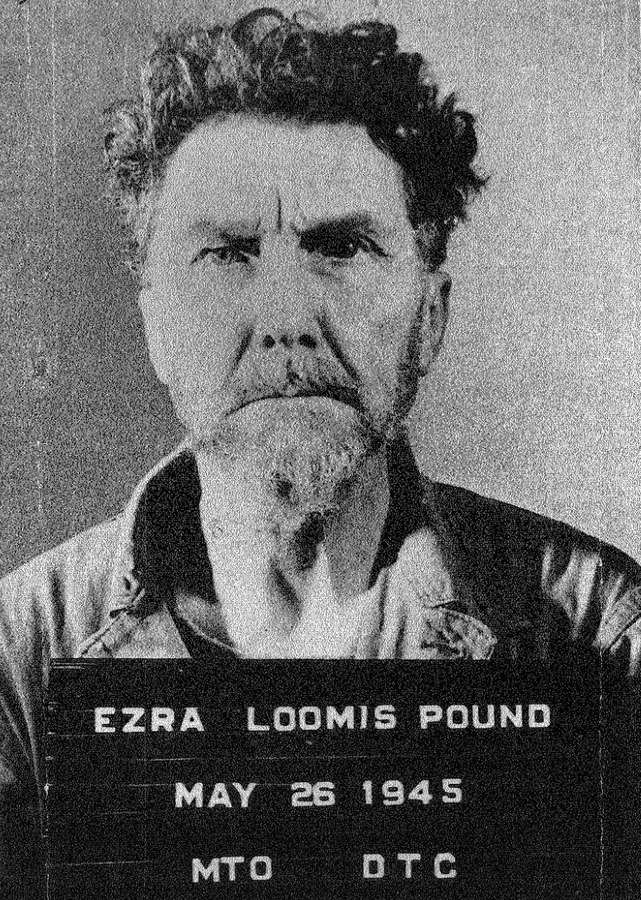

She made friends in the 1940s with the poet Ezra Pound (1885–1972), a fellow popularizer of the Classics (albeit in a very different way), who was imprisoned for treason after World War II. Pound and Hamilton had distinctly opposed political views (Pound being notoriously a fascist); Hamilton also abhorred the ‘Modernist’ literary and artistic movements of which Pound was a leading figure. But she warmly appreciated Pound’s eccentric 1954 translation of Sophocles’ Women of Trachis. Their shared love of Greek and Roman Classical literature helped them transcend their otherwise irreconcilable differences, and gave Hamilton a reason to overlook Pound’s often awful political views.

Hamilton’s 1957 The Echo of Greece emphasized the moral responsibility of citizens in a democracy. It was a Book of the Month selection, and won admiration from academic Classicists, including Werner Jaeger (1888–1961), author of the celebrated multi-volume study Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture (1933–47), as well as Richmond Lattimore (1906–84) and Robert Fitzgerald (1910–85), the most celebrated American translators of Classical literature in the 20th century. Hamilton, Lattimore, and Fitgerald all helped to usher in an era of the democratization of Classics in which it became acceptable (at least in some quarters) to read these works in translation.

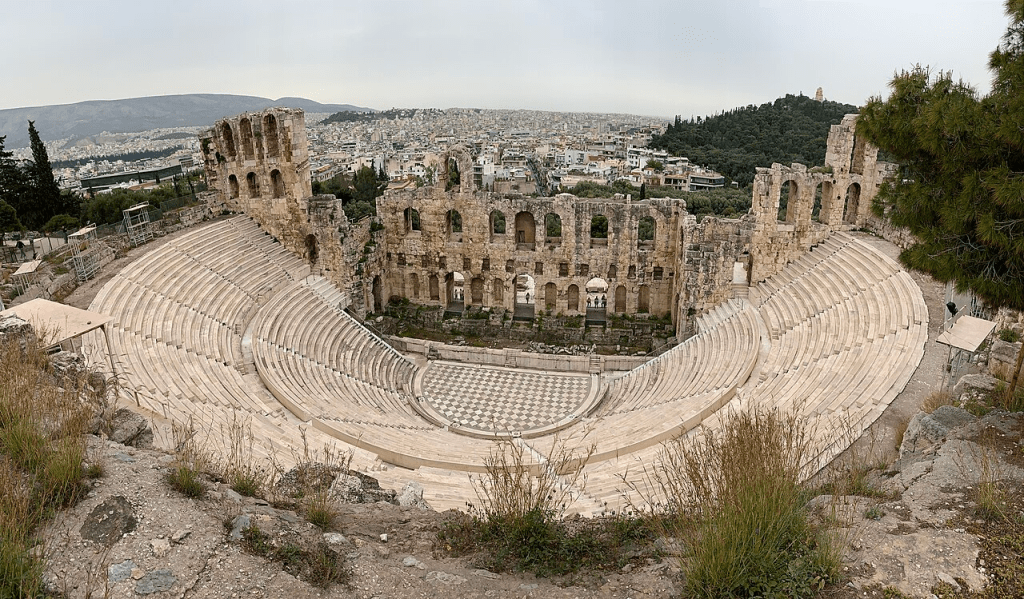

In 1957, Hamilton traveled to Athens to see her translation of Prometheus Bound be performed in the Odeon of Herodes Atticus on the slopes of the Acropolis. This event was significant during the Cold War: the former American president, Harry S. Truman, was trying to bring Greece into the alliance of Western liberal democracies. The production of the play, as well as Hamilton’s visit to Athens, was thus a political as well as a cultural event. Hamilton was later asked by the US Information Agency to speak for the Voice of America (the agency’s anti-Communist international radio network).

Interestingly, Hamilton objected to the US federal government’s emphasis on education and culture as a weapon against the Soviet Union. She considered state-imposed educational policies to be in direct conflict with American-style individualism, and the freedoms that she cherished. She did, however, argue to the Classical Association of the Atlantic States that the study of Classical languages would help maintain the spirit of liberty within Western democracies during the Cold War.

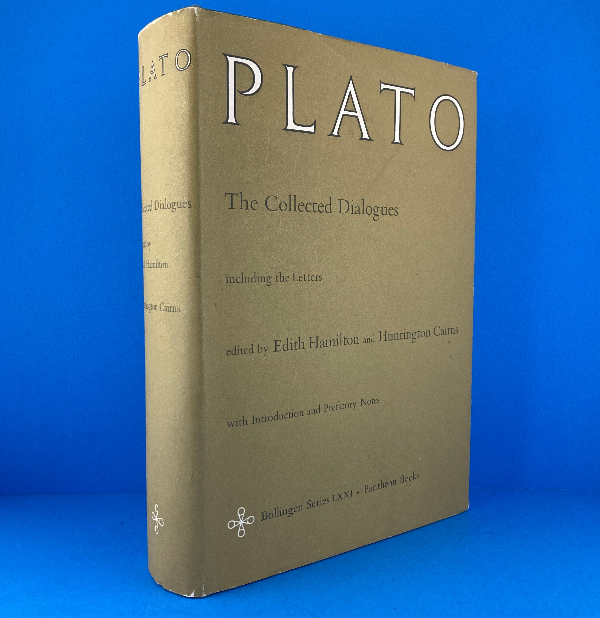

Late in life, Hamilton was made a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and began to appear on television, as well as in popular magazines including Harper’s Bazaar and Life. She spent 1958 writing introductions to a new edition of The Collected Dialogues of Plato, calling this her “year with Plato”, but continued to receive visitors from the Washington elite, considering an active life to be in line with the Greek ideal.

Edith Hamilton died of a heart attack on May 31, 1963 , at the age of 95; she was buried in Cove Cemetery in Hadlyme, Connecticut. Her many works continue to be read over six decades after her death.

Paradoxically, (or perhaps not) this American Dame of Classics has come under criticism for her apologiae for the Classical world and Western civilization. A recent biography of Hamilton by Victoria Houseman has appeared from Princeton University Press. At least one reviewer has taken the opportunity to criticize some of Hamilton’s allegedly “insensitive” and “triumphalist” comments on Greece and Western civilization. Hamilton has also been criticized for ignoring the irrational and Dionysian side to Greek culture.

But anyone can find anything they want in the Classical world. People have used Classics for all ideologies, and will continue to do so. In her time, Edith Hamilton used the Classical Athenian ideal as a focus for the struggles between liberal democracies on the one hand, and fascism and communism on the other. Yet the enduring fascination of Hamilton’s work demonstrates that Classics cannot be bound or contained by any political ideology, and will always remain, for us and for anyone else, an “ever-present past”.

Associate Professor of English at Georgia Southwestern State University, Jesse Russell has published in academic journals such as Texas Studies in Language and Literature, New Blackfriars, Renaissance and Reformation, and Explorations in Renaissance Culture. He is also the author of The Political Christopher Nolan: Liberalism and the Anglo-American Vision. His second book, Magic and Queenship in Spenser’s Faerie Queene is forthcoming from Palgrave Macmillan.