An Antigone interview

Over the course of a long and distinguished career, Dame Averil Cameron has published a dazzling array of studies of late antique Roman and Byzantine history, while writing also on the history of women and the history of Christianity. She kindly agreed to answer some questions posed by Gavin McCormick for Antigone on a range of topics, dealing with her career as a historian, and touching on some changes she has witnessed in education and academia.

GM: The study of late antiquity has developed a great deal over the past few decades, and you have been a central figure in this development. Late antique history used to be something Classicists and ancient historians didn’t really consider much – but there is burgeoning interest in the discipline. Could you highlight some of the major changes you have seen in this area, and whether you feel there is progress still to be made?

AC: I’m not sure about “dazzling” but yes, I have published a lot – I often think too much. I could have focused more but I was too ready to say “yes”, and always interested in moving on. The current debates about late antiquity are about how long it lasted. It is even argued that it continued until the end of the first millennium, but historical periodization can be much too artificial, and this begs the question of its relation to Byzantium.

GM: Could you tell us a little about what brought you to Classics when you were in school? And what was it that led you to the study of late antique writers?

AC: I came to Classics in the canonical way, through a teacher at my not very academic girls’ school. Without her I might have done Music under the influence of our Miss Brodie-like Music mistress, but she and the headmistress pointed me in the right direction. My Classics teacher also introduced me to John Pinsent, who was a lecturer at Liverpool, and he told me I must go Somerville College in Oxford and read Greats, because I would be taught philosophy by Elizabeth Anscombe, as indeed I was. Reading Greats was one of the best things I ever did and gave me a grounding that has stayed with me ever since in ancient history and philosophy, as well as language and literature, and I am very grateful. There were some severe limitations in the coverage but that methodological spread later made an interdisciplinary approach natural for me.

I started work on Agathias after Isobel Henderson, my ancient history tutor at Somerville, sent me to ask Robert Browning in London for advice about a possible PhD topic. In London I was very much influenced as a historian by Arnaldo Momigliano, and I’m sad that he is now so much less remembered here than in his native Italy. His influence was hugely important in directing me towards questions of historiography rather than philology or literary studies (even though my first job was in Classical Literature). I was also incredibly lucky to have a year in the US teaching in the graduate school at Columbia University in the late 1960s. It was an eye-opener in many ways, not least because it introduced me to the early stages of second-wave feminism as it was being experienced by American women Classicists.

GM: From a Classicist’s point of view, what are the special challenges involved in reading Byzantine Greek texts?

AC: It depends on what you regard as Byzantine, and although I have worked on texts I have always considered myself as primarily a historian. As such, I’ve always been drawn to new topics. That is what I found exciting, and it explains why I first worked on the later Romane Empire after Greats. On the other hand, many people would regard 6th-century authors like Agathias, Procopius and Corippus as Byzantine, so I was aware of Byzantium and interested in it at an early stage.

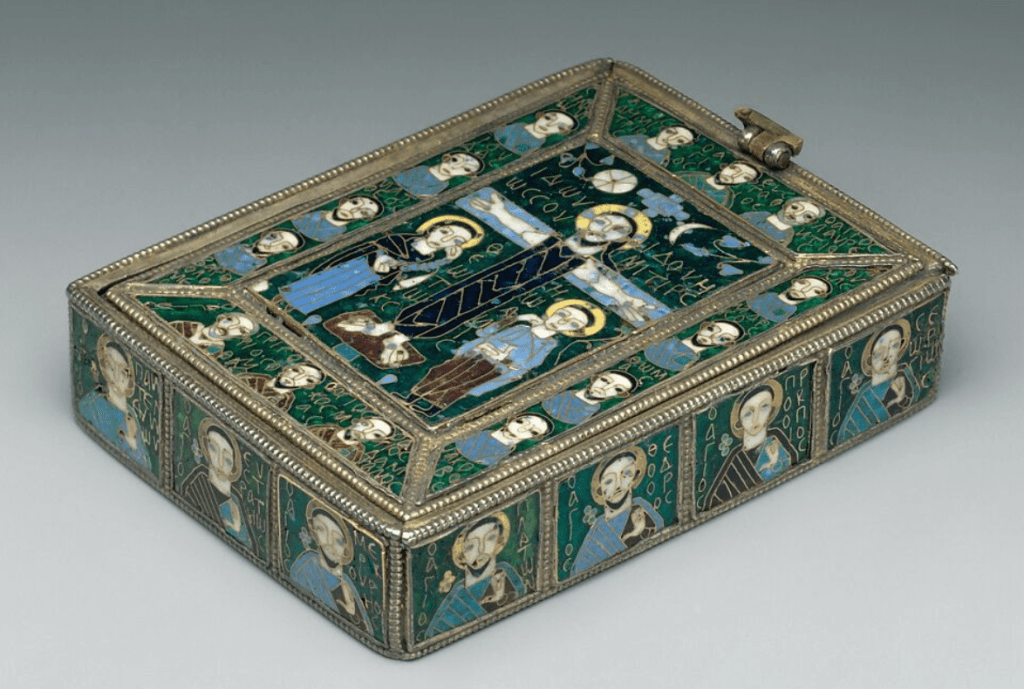

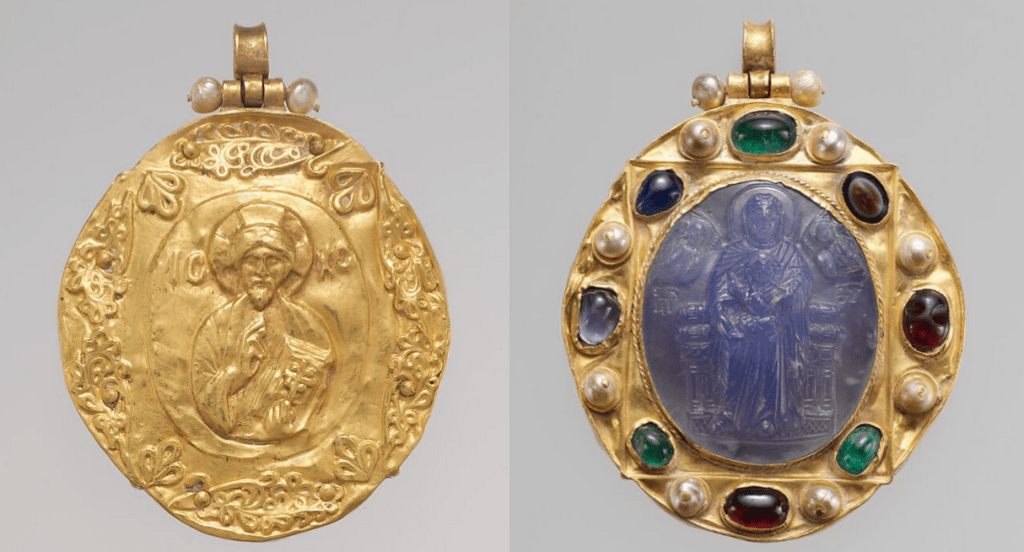

Intellectual curiosity often drove me to move into new fields, for which I had to explore material that was unfamiliar to me, including archaeology and art history, that is, what is now known as material culture. The development of late-antique archaeology from the 1970s was a huge breakthrough, and as visual art is so important in Byzantine culture I went out of my way to acquire a grasp of the key examples, which are just as important for a historian as the literary texts. I also had to plunge into New Testament criticism and early Christian texts for my Sather Lectures in the late 1980s, and I now realise how lucky I was not to have any constraints on what I worked on. It would be much harder for young scholars now to be led into new territory in the ways I have been.

GM: You have published on several individual late-antique authors (Eusebius’ Life of Constantine, Agathias, Procopius). Of those authors and texts with whom you have spent a lot of time, do you have a favourite or favourites?

AC: We didn’t call them late antique in those days and I’m not sure I have a favourite exactly. My work on Eusebius arose from holding a seminar at King’s College London after I had become interested in the history of early Christianity, and that was also true of other texts on which I’ve published, like the late 6th-century Life of the patriarch Eutychius and the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai, on which I worked with Judith Herrin and several others. Images of Women in Antiquity, which I co-edited with Amélie Kuhrt, also arose from a seminar, but at the Institute of Classical Studies. Eusebius fed into other subjects, especially the Emperor Constantine and the development of asceticism, and the Life of Constantine was a perfect illustration of how Christian authors used literary devices to get their arguments across (I called it rhetoric, in a broad sense, but others might see it as manipulation). I argued for the importance of this Christian rhetoric in Christianity and the Rhetoric of Empire.

GM: What should you study before reading the Byzantine historians? Is it wise to tackle Procopius before you have gained good familiarity with Thucydides?

AC: It certainly helps to know something about Classical historiography, because it was important to most of the Byzantine historians and you need to be able to understand their references and their techniques, but a lot can be done through translations. Knowing some Tacitus is a great help when studying Ammianus for example, and so is Thucydides for Procopius (not forgetting Herodotus). Having been a Classicist helped me, although there’s always the danger of over-emphasising the Classical element – less the case now that people come to Byzantine studies from so many more backgrounds and when our understanding of the subject is so much wider. Graduate students working on late antiquity and Byzantine studies in Oxford now work on topics relating to western medieval studies, early Islam and beyond, and on material in many languages other than Greek, especially Syriac but also Arabic, Georgian, Armenian, and more, even Middle Persian. I think this breadth is one of the best things that has happened since I started out.

GM: What works of scholarship might you single out as the great contributions to the study of late antique and Byzantine history of the past few decades?

AC: Peter Brown’s World of Late Antiquity, of course, but it’s harder to point to a really great contribution to Byzantium because Byzantine studies have not yet fully extricated themselves from the prejudices of the past. As I’ve argued, Byzantium is more often than not totally ignored in mainstream history and I have written about Byzantine studies and Orientalism and other problems in Byzantine Matters and elsewhere. The field has moved on but many of these issues are still with us and they are the subject of lively discussion – try for example “What Do We Get Wrong about the Byzantine Empire?” in the current issue of History Today.

GM: One of your major contributions to scholarship was your editorship of three volumes of the new edition of the Cambridge Ancient History (CAH). Could you talk a little about the experience of being involved with that project?

AC: Anyone who has done it will tell you that editing large collective volumes can be painful and does not always result in the way you had planned. We also inherited a format already used in eleven previous volumes and following the example of the original series that had started in the 1930s. Volumes 13 and 14 were completely new (the original CAH had ended with Constantine), but they still largely followed this overall plan in their structure, although we tried to do justice to the history of the later Roman Empire as it was developing at the time. For instance CAH 13 notably included chapters on asceticism, orthodoxy and heresy and Christian writing. Apart from choosing the contributors and topics we did not attempt to impose an editorial view, so the result is necessarily uneven, and from the perspective of the developing field of late antiquity the end date, which owed much to the periodisation adopted in A.H.M. Jones’s Later Roman Empire, is clearly too early. But I think these new CAH volumes do demonstrate a field that was then in transition.

GM: You served as Warden of Keble College, Oxford, for sixteen years, while also acting as a Professor and university Pro-Vice-Chancellor at Oxford. You served also as a Professor and Lecturer at King’s College, London for many years. We are interested to hear your thoughts on some of the broad shifts in education, especially university education, over the past decades.

AC: I spent more of my working life at King’s College London than at Oxford, and both the University of London the University of Oxford have changed greatly. Both have grown enormously in size and now admit a far higher proportion of international and graduate students. They both place much more emphasis on research, and while this is partly due to pressure from the Research Excellence Framework and the like it has also been a wider trend, making university life more stimulating and broadening everyone’s experience. Academic life is certainly harder and more competitive now but of course challenge is also good.

GM: If you could devise an education policy relating to universities (or indeed in general) for the 21st century, what might this look like?

AC: I would change the current funding model for universities because it is distorting for the institutions, ruinously expensive for students and especially hard on early-career academics. I would encourage overseas students, not denigrate them, because I believe internationalism is good for everyone, and am also a strong believer in the value of international research programmes, conferences and seminars. I would give much more support to humanities, which are the foundation of civilization and cultural understanding and yet are under real threat. Like so many other public institutions universities are currently suffering the results of ignorant and prejudiced political and media coverage. Their value is too often seen only in financial terms, but education and independent thought are fundamental.

GM: Could you talk a little about what drives you to keep publishing and researching, and what continues to excite you about the world of Byzantium in particular?

AC: Very few of my academic friends and colleagues stop working when they officially retire, and they often then produce publications they had been prevented from completing before by their university obligations. It’s not a question of why we go on, but of why should anyone think we would not? We go on because we enjoy it and think it matters, and it’s a great privilege to have been in a career that has offered so much personal satisfaction.

GM: Thank you very much for taking the time to talk with us. It has been a pleasure.

Averil Cameron taught at King’s College London and was Warden of Keble College and Professor of Byzantine History at Oxford until she retired in 2010. She lives in Oxford.