Marek Węcowski

In memory of Kurt A. Raaflaub (1941–2023)

Long before Plato and Aristotle, and, even before the so-called ‘sophists’ of the 2nd half of the 5th century BC, the natural medium of Greek political thought was poetry. This was true from the very beginning of its known history.

Following the footsteps of the late Kurt A. Raaflaub, let us note that the Iliad and the Odyssey are essentially political treatises; both tell us a similar story. The Iliad is a monumental tale depicting the aftermath of a clash between the Achaean leaders at Troy over booty and, through this means, over prestige and dominance in their community. The leader of the expedition, Agamemnon, has deprived Achilles, the most powerful Achaean warrior, of his favourite captive Briseis. Humiliated, Achilles refuses to fight further, and thus deliberately sends hundreds of his countrymen to meet their death on the battlefield. All this was done purely to make everyone, and Agamemnon in particular, regret that mistake and restore the honours due to Achilles. From this point onwards, the poem deals with the consequences of Achilles’ decision, which essentially involves the conflict between the community’s interests and the ambitions of an outstanding individual who can barely find a place for himself in that community.

From its very first line, the Iliad immediately foreshadows the tragic consequences of “Achilles’ wrath” (Iliad 1.1). In much the same manner, in the Odyssey we learn from the beginning that Odysseus, king of Ithaca on the Ionian Sea, and commander of its army sent to the Trojan War, failed to save what was left of his army returning home, “though he tried hard” (Odyssey 1.5–6). From the story told by Odysseus himself when among the Phaeacians, we learn about the successive stages of his ten-year wandering. At each turn of this long journey back home, the hubris, curiosity, or simple carelessness of the leader leads to the death of successive members of his team. Ultimately, he is left all alone, although his divine protector Athena keeps him safe throughout all these situations.

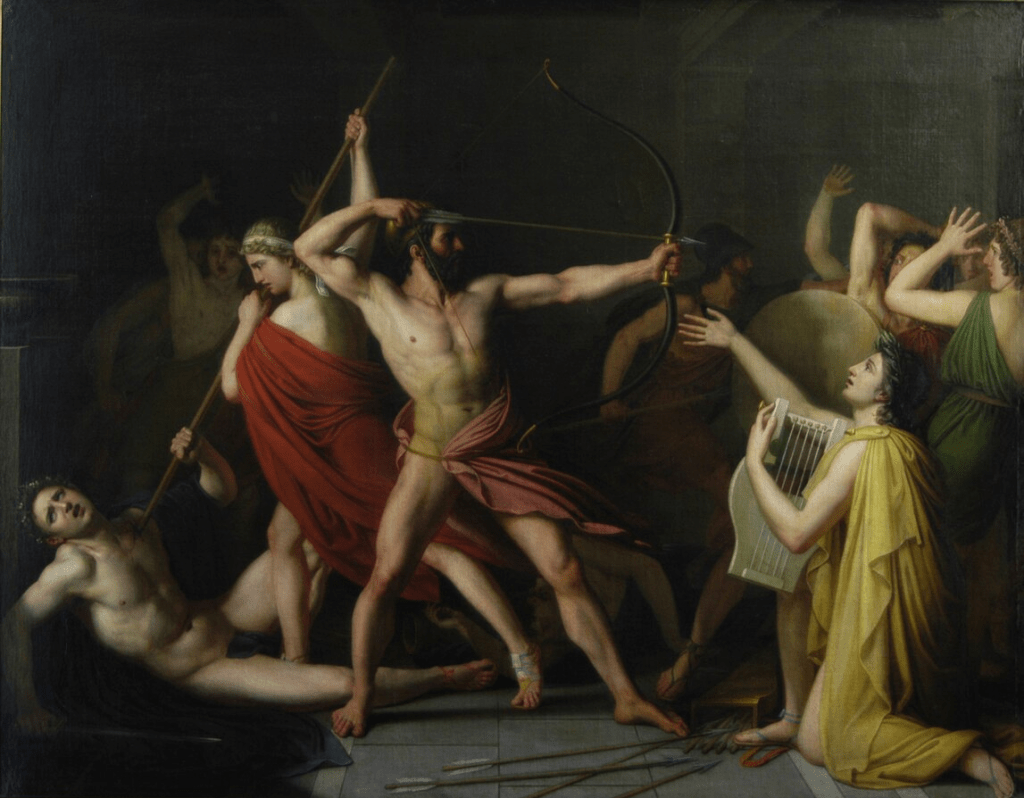

When Odysseus finally returns home, he wreaks vengeance on the persistent but also utterly defenceless suitors of his wife Penelope. Thus, he murders the next generation of his kingdom’s youth, who were, in part, the younger brothers of the unfortunate participants in the Trojan War. No wonder some of Ithaca’s citizens rose against him, supporting the vengeful families of the murdered young men. Only Athena’s supernatural intervention extinguishes the flame of civil war and miraculously restores harmony to a community that has been so sorely tried.

The disasters and suffering that result from the overambition of leaders are almost ubiquitous as a subject or theme throughout early Greek poetry. Hesiod lived in Boeotia in central Greece at the turn of the 8th and 7th centuries BC. In his Works and Days, the iniquity and injustice of political leaders in their ancient function as judges of the community form a recurring motif. Hesiod declares that the entire society will be held responsible for the “crooked verdicts” of their judges, because human justice is at all times overseen by god (or the gods), and for its violation, the deity will exterminate entire communities ruled by the unrighteous:

Often even a whole city suffers for a bad man who sins and devises presumptuous deeds, and the son of Cronos lays great trouble upon the people, famine and plague together, so that the men perish away, and their women do not bear children, and their houses become few, through the contriving of Olympian Zeus. And again, at another time, the son of Cronos either destroys their wide army, or their walls, or else makes an end of their ships on the sea. (Works and Days, 240-8, tr. Hugh G. Evelyn-White)

Hesiod, drew here (perhaps indirectly) on oriental models: in Babylonian wisdom literature and even in the prophetic books of the Old Testament, this aspect of justice often comes to the fore. Like the biblical prophet, the Greek poet can warn and exhort but has little hope of being listened to.

* * *

What is “best”, “strongest”, or “most valuable”?

Beginning with Hesiod, wisdom literature would evolve into an important thematic strand of Greek poetry that was performed primarily at all-night aristocratic feasts called symposia (literally “drinking together”). The later Greeks called this sort of verse Hupothēkai, “Teachings” or “Submissions.” Such verse includes reflections on often political topics; the form partly originates from convivial games of riddles centring around a question posed to the revellers, to which each of them, one after another, was compelled to answer in a suitably brilliant and, therefore, often paradoxical way: a sample question would be: “Who is to blame for the disaster of the community?”

This, by the way, is just one variation of the Greeks’ favourite pastime over wine, when the tricky question might also arise of what is “best”, “strongest”, or “most valuable”. A deity? Time? Gold? Or perhaps friendship? Or maybe water, always essential to life, as one of the greatest Greek poets, Pindar (like Hesiod a Boeotian), will answer in the 5th century BC? Or is it simply humans themselves, as in the famous chorus from Sophocles’ Antigone? In the days of the Roman Empire, in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, this question would entertain intellectuals such as Plutarch from Chaeronea (also in Boeotia). This game of riddles would also occupy Greek sages and philosophers. When, in Plato’s Symposium, the praise of Eros becomes the subject of rhetorical displays by Socrates, Aristophanes, and their friends at a symposium given by the poet Agathon, we see how the general question of what is “best”, “most precious” or “most potent” is reduced to the subject of love.

Referring to Hesiod, whose wisdom from Works and Days was certainly quoted at symposia on such occasions, Solon, the Athenian poet, politician, and reformer of the early 6th century BC answers the question of the most common culprits for political problems or even the annihilation of entire civic communities:

Our city will never perish because of Zeus,

Or through the plans of the happy immortal gods—

For our guardian is great of spirit: the one born of a mighty father,

Pallas Athena holds her hands over us.

But the very citizens plot to destroy this great city

being dragged off by wealth in their folly.

The leaders of the people think unjustly, and

in their arrogance prepare to receive great pains. (Solon, fr. 4 W2)

Here we see how Greek political reflection consciously pits the leaders of the community against ordinary citizens, with both sides of this political opposition assigning equal blame for public misfortunes, but taking it off Zeus. It is the people, not the wrath of the gods, who threaten the polis as we know it. In both cases, the motivation of the corrupt elite and the people is the same – greed and lust for material gain lead to a blindness that is dangerous for all.

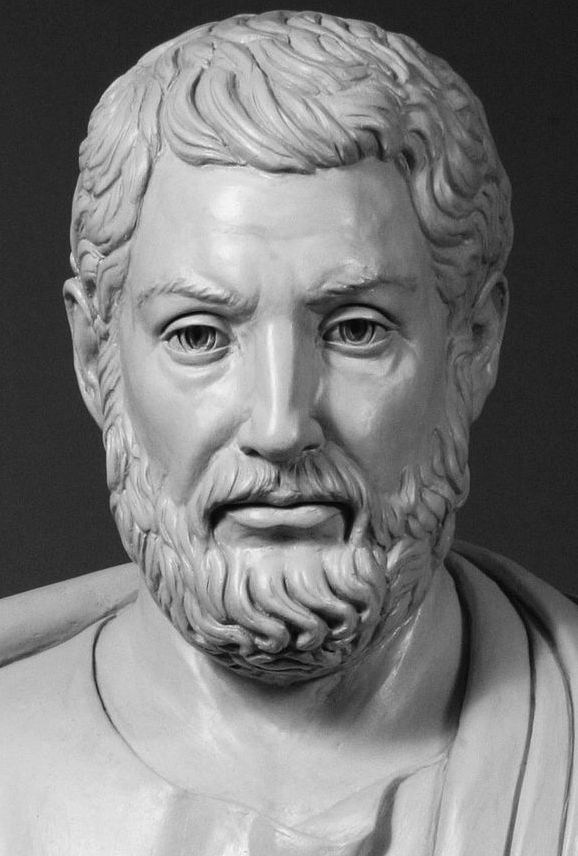

Later still, Hesiod’s poem is alluded to by Theognis of Megara (most likely Megara on the Isthmus of Corinth, but possibly from Megara in Sicily), a generation or two later; the following is no doubt a reply to Solon (‘Kyrnos’ is either a fictional or real young man, the recipient of the poet’s instructions):

Kyrnos, this city is pregnant, and I fear that it will give birth to a man

who will be a straightener of our base hubris.

The citizens here [in the city] are still moderate, but the leaders

have veered so far as to fall into debasement.

Men who are noble, Kyrnos, have never yet ruined any city,

but when people who are base decide to behave with hubris,

and when they ruin the community and render judgments in favor of the unjust,

for the sake of private gain, and for the sake of absolute power,

do not expect that city to be peaceful for long,

not even if it is now in a state of great serenity,

once the base decide on these things,

namely, private gains entailing public damage.

From these things result acts of discord, killings within local groups of men,

and one-man rulers. May this city never decide to accept these things!

(vv.39-52, tr. G. Nagy)

Note the beautiful metaphorical image of a homeland (polis, here rendered as “city”, is feminine in Greek) that walks in advanced pregnancy about to give birth to a tyrant. It would be hard to find a more moving description of a community threatened by authoritarian power. A community for which, however, a violent tyranny would be a well-deserved punishment.

In this poem, Theognis goes even further than Solon. It is neither the wrath of the gods nor the actions of the citizens that threaten the entire community. As in Hesiod, it is always the leaders who are to blame. It is from them, as the aristocratic poet self-critically observes, that political and moral corruption begins; they set a bad example to the people by misusing their function as judges. The evil here is very concrete: the pursuit of material gain, as in Solon’s case, but also of political power, authority, or significance (the Greek kratos, literally “force”).

In the modern era, Theognis has commonly been seen as an exemplary oligarch, or a radical supporter of the aristocratic monopoly of power. In other poems, he denounces the excesses of the demos, the mingling of old and new blood, and the misalliance between representatives of the old elite and the nouveaux-riches. There is undoubtedly a good deal of truth in such interpretations. However, as in many other passages in his poetry, his thought is much deeper and more subversive and perhaps innovative.

In the poem quoted above, the poet has set a trap for the reader by playing with the ambiguity of the terms (and concepts) “noble” (Gr. hoi agathoi, literally, “the good ones”) and “vile” (Gr. hoi kakoi, literally“the bad ones”). The primitive or simple-minded aristocrats, like various “elitists” to this day, identify the former with people of “good” pedigree or substantial wealth, attributing to them moral qualities and good political intentions. Conversely, in the eyes of such an old-school conservative, people coming from lower social strata will be inherently morally bad, or at least stupid in politics, and most often simply harmful. In his poems, Theognis challenges this simplistic set of oppositions in a number of ways. His most important observation is that, in politics, an individual who is “good” in terms of pedigree or wealth can be, and perhaps most often is, morally bad, and thus fatal to the polis.

Theognis’ poems are a kind of speculum principis, educational poetry addressed to young aristocrats to prepare them for political and social life, mainly by showing them clearly who is truly “good”, being – as we would say today – at the same time an aristocrat of origin, spirit, conscience and, to put it somewhat anachronistically, a true patriot. This is the only company, Theognis argues, that a young man should seek if he wishes to become so comprehensively “good”, avoiding all those who are “aristocrats” only nominally, or by their own declaration, or with respect to the tastes and preferences of their social peers. A true aristocrat is only one who simultaneously fulfils all the above criteria – moral, political, and social. As we can see, whatever Theognis’ social ideas really were, we witness here the first frontal attack on primitive elitism in the history of our culture.

* * *

Acts of discord

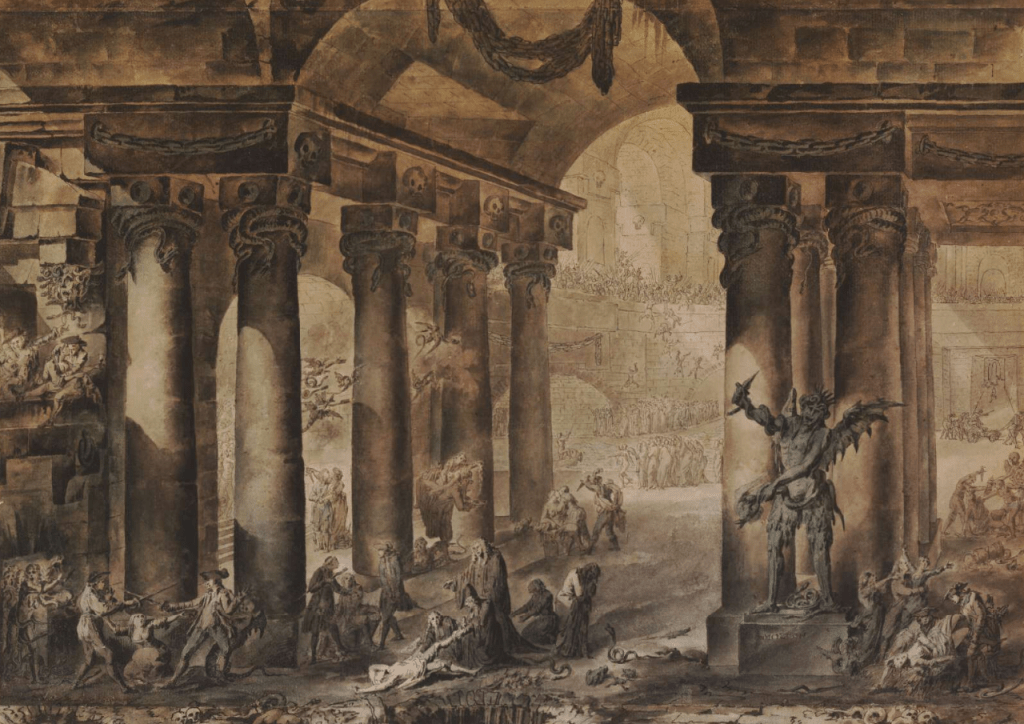

Theognis’ poem above ends with a lightly-sketched but extremely powerful picture of the impending political apocalypse: “From these things result acts of discord, killings within local groups of men, and one-man rulers.” “Acts of discord” is staseis in Greek, the plural of stasis, and it is one of the most important terms and concepts of Greek political thought. In Aristotle’s political theory, stasis is one of the essential themes of reflection on the causes of regime change (Gr. metabolē), such as the transition from democracy to oligarchy (or vice versa), as an almost inevitable conflict between more powerful or wealthier citizens and the common people. For Aristotle in his Politics, this is one of the obvious “givens” of Greek polis life.

Modern scholars of Greek politics have always been fascinated by a surprising linguistic fact. In Greek, the word stasis covers a wide range of political phenomena – from an organized political group to a civil war or even a coup d’état carried out by enemies of the ruling “party”. If we simplify a little, therefore, it can be said that, for the Greeks, a political plot or backroom agreement by a group of citizens was only one step away from armed action against the ruling authority.

This should not surprise us too much for a world in which, since there were no clearly defined political parties, political activity was purely partisan business by small circles of friends and relatives. Any action to gain power takes the form of a secret union of people bound together by ties of strict loyalty in a clandestine enterprise that is fraught with the highest risk if discovered.

Such was the case of Theognis, who refers to the political plans and agreements of the “friends” (Gr. hetairoi) conspiring at their all-night banquets in coded terms such as “the great deed” or “the most serious matter”, without any further elaboration. These conspiratorial euphemisms demonstrate well the nature of Greek political struggles and the constant danger of exposure associated with them. The necessity of staying in a circle of people devoted to each other ultimately explains to us the significance of the teachings of Theognis. What he offers to his disciples is a way to recognize unmistakably trustworthy “friends”, namely those who are genuinely “good” or noble in the political, moral, and social sense of the word simultaneously. Companions of one thought and a shared system of values are yet another ideal uniting conspirators of all times.

In Greek political life, the victorious group, or stasis, will often set about persecuting its opponents – with their actions ranging from the appointment of magistrates by “their own”, to political exiles, the requisitioning of their property, and, in a particularly fraught situation, to the political murder of their enemies.

* * *

The wisdom of Cleisthenes

The permanently unstable political life, the conspiracies, the constant danger of political upheaval and its grim consequences are endemic phenomena of Greek politics – from Homer through to Alexander the Great. All this was ultimately dealt with by prevailing external forces (first Alexander himself, then his Hellenistic successors, and finally the Romans) that curtailed the autonomy of the Greek poleis in order to maintain the internal peace and order of their empires. Before this happened, however, some Greek communities tried to cope somehow.

At the dawn of Athenian democracy, in 508/507 BC, the reformer Cleisthenes invented ostracism, an annual vote on whom to banish for ten years on the ground that he, in the opinion of the majority, would threaten the state. This was a relatively lenient measure, since the ostracised figure would go into exile honourably, without confiscation of property, let alone the risk of death at the hands of political enemies. The measure forced the quarrelling Athenian elite to keep the temperature of their political disputes sufficiently low that every year they could agree to vote “no” when the People’s Assembly was to decide whether exile in a given year was needed. It was a logical option. Every influential politician felt threatened because no one could be sure of the final decision of the proverbially unstable and unpredictable demos. Thus, Cleisthenes cleverly used the self-preservation instinct of the Athenian elite to minimize the danger of stasis in Athens.

In Sparta, on the other hand, the (not very numerous) citizens had already been privileged to such an extent – at the expense of political enslavement and economic exploitation of all other inhabitants of the polis – that they formed a radically elitist political organism, internally cohesive and loyal to each other, in which the risk of stasis was thus reduced to a minimum. As a precaution, however, potential schisms among the citizens were counteracted by, among other things, the highly exotic method of voting in the Citizens’ Assembly. Spartans voted for or against specific decisions by shouting; the strength of each faction’s collective shout was judged from afar by magistrates. The proposal for which the citizens shouted louder was the one which won.

Before commenting sarcastically on this practice, let us note that in such a system, the shouting minority, whenever it exists, will always prevail against an undecided, distracted, or simply opinionless majority. This, in turn, means that the polis will not be threatened by the occurrence of decisive action by the divisive minority, which could incite rebellion and unleash an internal struggle.

Of course, in the political realities of modern democracy, one dreads to think where a similar arrangement in our political bodies would lead. But for a safeguard against stasis, it was a very sensible idea. Citizens who did not have clear views on an issue and did not organise themselves adequately to shout down their opponents simply lost their influence on the community’s decision. But they were not the ones who threatened its cohesion after all! Today, we too often forget that the noisy minority is an important political factor that must necessarily be taken into account in the practice of majoritarian democracy.

* * *

The Thirty Tyrants

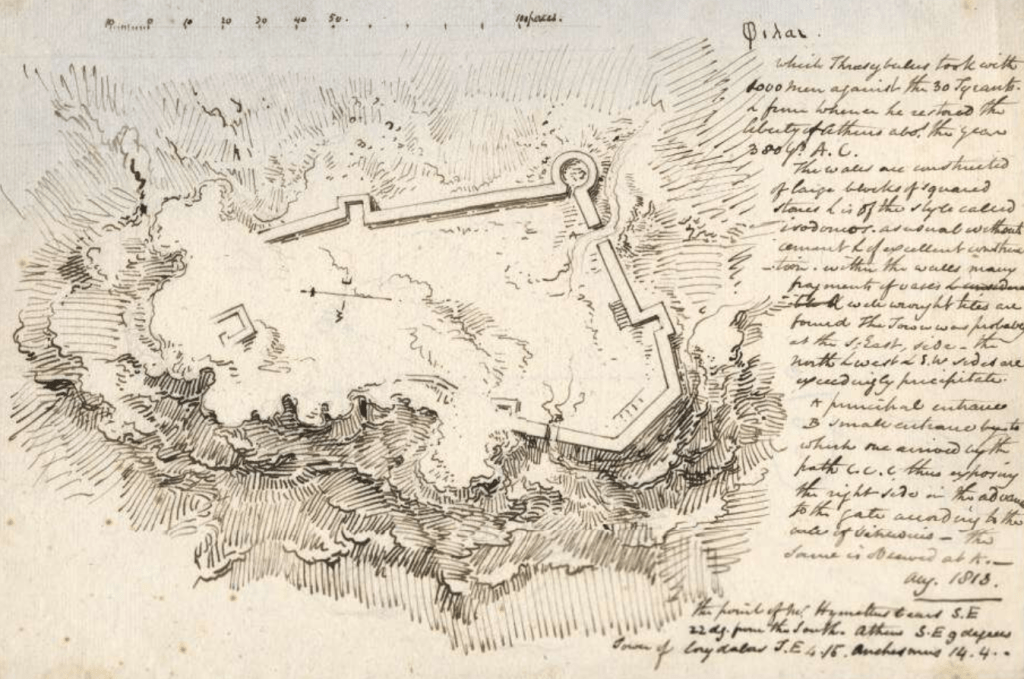

Historically, the best known to us, but also perhaps the most instructive example of Greek stasis was the events that took place in Athens in 403 BC. After their defeat in the Peloponnesian War with Sparta (431–404 BC), the Athenians lost their imperial position in Hellas, their army, and their entire fleet, and were forced to demolish their defensive walls. They also lost many sincere supporters of democracy, who had to flee the city. Athens was forced to accept the rule of an oligarchic clique appointed by Sparta. Its leaders, the most important of whom was the eminent intellectual Critias, the versatile poet, writer, and uncle of the youthful Plato, turned out to be bloody autocrats; later tradition even called them the “Thirty Tyrants”. The more they struggled with the post-war political, economic, and social crises in Athens, the harder they persecuted their increasingly reluctant citizens.

Not surprisingly, the democratic rebels, fortified at first in the mountain fortress of Phyle north of the city, rapidly gained support. When the time came, they moved under arms into the valley. The decisive, extremely fierce battle between the oligarchs’ supporters and their enemies took place in the Athenian port of Piraeus. The oligarchs were aided by the Spartan garrison, which repulsed the rebels; but the latter’s forces were growing. In this situation, the Spartan king Pausanias himself secretly instructed both sides on how to negotiate so as to convince Sparta to stay neutral on the further fate of the Athenian polis. The supporters of the oligarchy and the democrats were now to agree on the future of Athens.

An unprecedented, and to this day shocking, solution was chosen, which was called amnesty, in Greek literally “letting go”. The most important stipulation of the agreement between the parties to the civil war was to provide full personal, political, and property security to the defeated. Those who felt loyal to the oligarchs and therefore threatened by the restored democracy could leave Athens and settle in the sacred place of Attica, Eleusis, the centre of the most important mystery cult of the Athenians. Henceforth, Athens and Eleusis, as the two halves of the Athenian polis, were to govern themselves separately and independently of each other, and only the mysteries of Demeter and Kore were to be celebrated together. Potential oligarchic fugitives (not exiles after all!) had ten days to declare and another twenty to implement their decision, but the democrats manipulated the deadlines so that as many oligarchs as possible would stay in Athens and feel the benefits of peace and tolerance from the new government.

Most striking, however, was another point of agreement, summarised by an unknown disciple of Aristotle, the so-called Pseudo-Aristotelian Athenian Constitution, as follows:

“And that there be a universal amnesty for past events, covering everybody except the Thirty, the Ten, the Eleven, and those that have been governors of Peiraeus, and that these also be covered by the amnesty if they render account.” (39.6, tr. H. Rackham)

As we can see, the amnesty did not extend only to the Thirty Tyrants and a few magistrates among their particularly hated helpers. But even this was on the condition that they would not submit a proper report (Gr. euthuna), which every Athenian official submitted at the end of their term of office, subjecting their actions in office to the assessment of the demos. In practice, of course, the worst oligarchs (some of whom, like Critias, had already been killed in battle) would have been duly punished precisely under the latter provision. Everyone else, however, would be safe.

It is said that the first Athenian democrat who dared to violate this agreement and began to “reminisce badly about past incidents” (presumably by publicly accusing some former persecutor of his) was immediately executed by the Council of Five Hundred, the most important democratic body next to the People’s Assembly. This example was meant to show that the agreement to “let go” of political pasts was deadly serious. However, our ideal picture is distorted by the story of Xenophon, historian and philosopher, disciple of Socrates, and rival of Plato (full of admiration though he was for Athenian amnesty). In his Greek History (Gr. Hellenica), he writes that some time later the democrats became suspicious that the oligarchs of Eleusis were gathering mercenary troops to strike Athens:

“So at that time they appointed their magistrates and proceeded to carry on their government; but at a later period, on learning that the men at Eleusis were hiring mercenary troops, they took the field with their whole force against them, put to death their generals when they came for a conference, and then, by sending to the others their friends and kinsmen, persuaded them to become reconciled. And, pledged as they were under oath, that in very truth they would not remember past grievances, the two parties even to this day live together as fellow-citizens and the commons abide by their oaths.” (2.4.43, translated by C.L. Brownson).

Note that the miraculous ending of the stasis and the extinguishing of the civil war after the massacre of the elite of one side of the conflict is reminiscent of the climactic scene of reconciliation from the Odyssey. Xenophon, like other Greeks, was simply thinking in Homeric terms, and it is difficult for us to get a true sense of how things really were.

* * *

A happy ending?

Some may say that the positive legend of the Athenian reconciliation is a great historical fraud. First, the compromise was just an illusion, a temporary ceasefire before the final settlement, when the democrats simply subjugated their former opponents by force, on this occasion by secretly murdering their leaders. Second, the rotten compromise, the “founding sin” of the renewed democracy, was left far behind. The bitterness caused by the lack of fuller reckonings with the past, of the personal tragedies suffered by the wronged without redress, led to festering wounds and acts of revenge carried out under false pretences. Some regard the trial and the death penalty of Socrates in 399 BC as an example of such revenge. He was a teacher of several of the oligarchic “Thirty” (including its leader, Critias) and a few other hated enemies of democracy. Beginning as early as Plato, these events would shape negative opinions of Athenian democracy for many centuries.

However, it is difficult not to admire the determination with which a compromise, necessary at a time of particular danger and state weakness, was adopted in the autumn of 403 BC and maintained for some time. Separating the parties to Greece’s greatest stasis while limiting ad hoc settlements to the leading culprits gave the polis invaluable time to recover from the disaster of a prolonged, devastating war, a crippling military defeat, and a period of brutal oligarchy. This solution probably did not satisfy any of the radicals, and certainly did not prevent the aforementioned individual tragedies and long-term internal problems of the community.

Meanwhile, it did allow Athens to be rebuilt, united, and finally strengthened quickly. Shortly after these events, Athens once again became one of the most important political players in Hellas. In the winter of late 404 BC, a handful of democratic rebels were returning stealthily from exile and found themselves freezing in the mountain fortress of Phyle, planning the liberation of their politically and economically ruined city, as well as the restoration of democracy. For their part,the people of Athens could not even dream of such a favourable political scenario as would materialise a few months later.

Marek Węcowski works at the Department of History at the University of Warsaw. He has published The Rise of the Greek Aristocratic Banquet (Oxford UP, 2014),Athenian Ostracism and its Original Purpose: A Prisoner’s Dilemma (Oxford UP, 2022), and Tu jest Grecja! Antyk na nasze czasy (This is Hellas! Antiquity now) (ISKRY, Warsaw, 2023). He has previously written for Antigone about Athenian democracy and Thucydides and the Ukrainian War.

Further Reading

E. Carawan, The Athenian Amnesty and Reconstructing the Law (Oxford UP, 2013).

H.-J. Gehrke, Stasis. Untersuchungen zu den inneren Kriegen in den griechischen Staaten des 5. und 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. (C.H. Beck, Munich, 1985).

K. A. Raaflaub, “Poets, lawgivers, and the beginning of political reflection in archaic Greece,” in C. Rowe & M. Schofield (edd.), The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought (Cambridge UP, 2000) 23–59.

M. Węcowski, Athenian Ostracism and Its Original Purpose. A Prisoner’s Dilemma (Oxford UP, 2022).