Mateusz Stróżyński

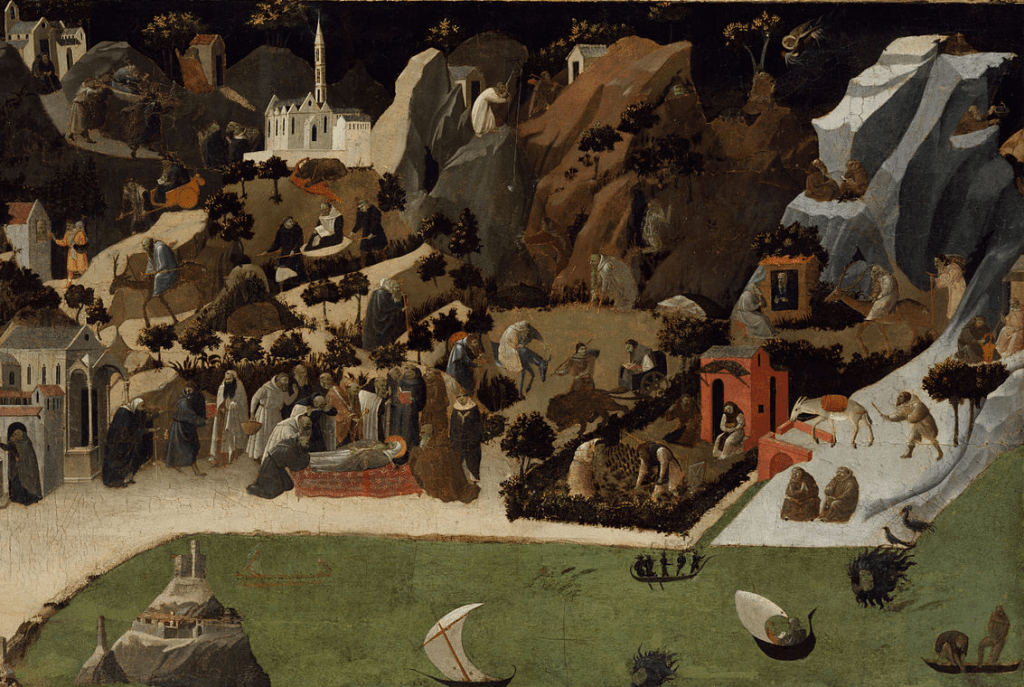

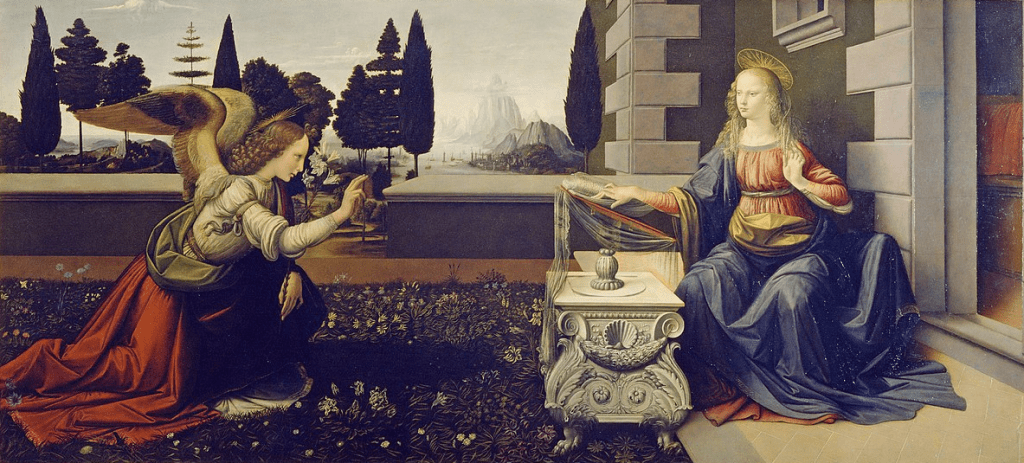

The main passages from the Gospels which are read and meditated on by Christians during the Christmas period are the well-known infancy narratives that are included in the first two chapters of Matthew and Luke. These have inspired Christian imagination for centuries. The great scenes of the Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Adoration of the Magi or the Flight to Egypt continue to shine and resound through great Western art and music.

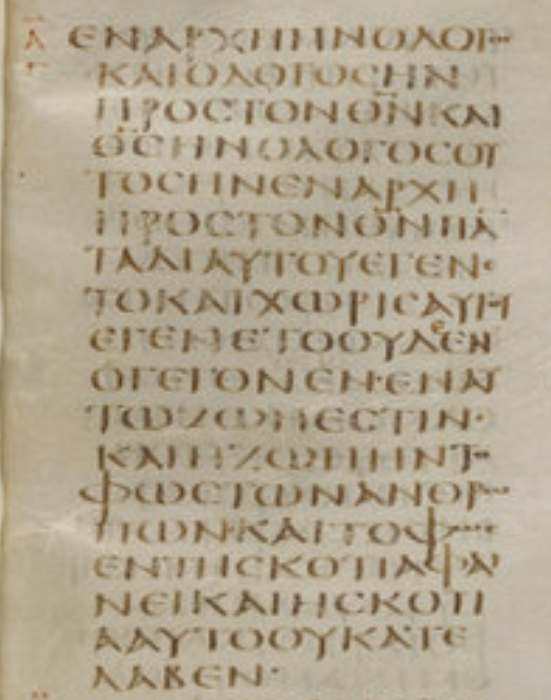

In a striking contrast to those vivid historiographic narratives (which are vivid regardless of their historicity – something fashionable to question nowadays) stands the Prologue to the Gospel of John, which is also read in Christian churches around Christmas. The text culminates in one of the most famous Greek and Latin phrases of Western history: ὁ λόγος σάρξ ἐγένετο (ho logos sarx egeneto), verbum caro factum est, “the Word/Logos became flesh” (Jn 1:14). The first verses of the Gospel of John, from 1 to 14 or from 1 to 18, has become known as the “Prologue” to the Gospel throughout the centuries, although, as Peter J. Williams shows, the oldest manuscripts don’t suggest that there is any real prologue in the text itself. However, the manuscripts still do signal that the first five verses of the Gospel form a distinct, introductory passage.

The Prologue (I will keep this traditional name) also refers to history, like the popular infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke, because it mentions John the Baptist[1] and also identifies the Logos made flesh as “Jesus the Anointed One” of Nazareth (Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Jn 1:17). However, still it is arguably one of the most philosophically and metaphysically rich passages in all Christian Scripture. Not to mention one of the most contemplative ones. John Scotus Eriugena, the 9th-century Irish monk living at the court of the Frankish emperor Charles the Bald, and the greatest philosopher of his time, begins his homily on the Prologue with the words: “the voice of a spiritual eagle strikes the ears of the Church” (vox spiritualis aquilae auditum pulsat ecclesiae; I.1).[2]

In my previous piece I wrote about the significance of “the way of the eagle” for the Western spiritual tradition. The eagle has been associated throughout the centuries with St John the Evangelist, in whom the Christian tradition sees the author of the Fourth Gospel, the most contemplative of these four texts. “The Beloved Disciple” has been seen as the symbol of contemplation, because he rested on the heart of Jesus during the Last Supper (Jn 13:23). For Eriugena, the Prologue is uttered by the voice of the eagle of contemplation, dazzling our sight as a lightning bolt and striking our ears as thunder (John and his brother James were called by Jesus Boanerges, “sons of thunder” at Mark 3:17).

The importance of the Prologue for the whole Christian tradition and, in particular, for the spiritual or contemplative tradition of Christian Platonism, is really hard to overestimate. St Augustine of Hippo makes an astonishing claim in his Confessions that when we compare the Prologue to the writings of Pagan Neoplatonists, the Gospel proclaims “not in the same words, but exactly the same thing” (non quidem his verbis, sed hoc idem omnino). The truth of Platonic metaphysics is expressed in the Fourth Gospel not through rational, philosophical arguments (multis et multiplicis rationibus), but through prophetic utterances, directly inspired by the Holy Spirit. [3].

In this way, however, Platonic metaphysics itself receives the stamp of divine inspiration, insofar as it is reconcilable with the Prologue to John. Owen Barfield (1898–1997), one of the most intriguing Christian Platonic and Romantic philosophers of the 20th century, and a close friend of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, had a habit of meditating daily on the Prologue, and dedicated to it one of his last essays, “Meaning, revelation, and tradition in language and religion”.[4] The importance of the concept of the Logos in the current wave of religious and metaphysical revival, which seems to be beginning anew in the West, also points to the continuous presence of the Prologue, and the power of the voice of the eagle, striking our dull minds with an ever-fresh energy.

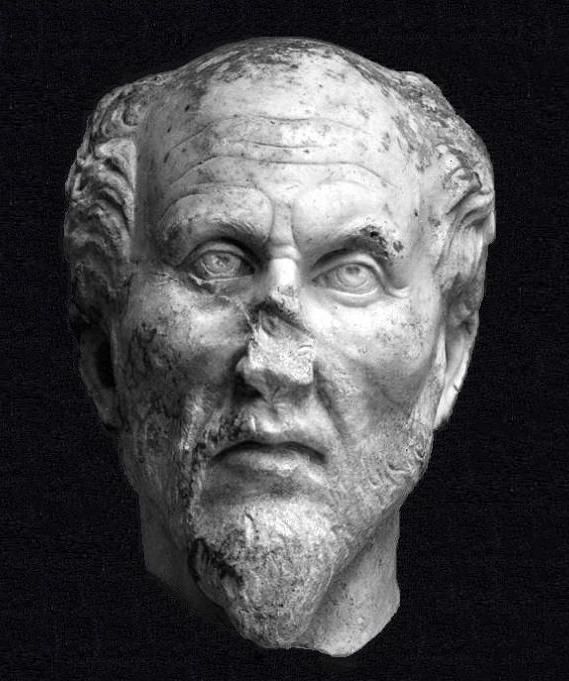

St John Chrysostom (AD 347–407), in his homilies on the Gospel of John,[5] seems to express a different view from Augustine’s, because he dedicates his second homily to proving that Greek philosophy is rubbish. In a lengthy tirade, Chrysostom asserts that there is no need to give any time to any Ancient Greek philosopher, except perhaps for Plato and Pythagoras, because their views on the nature of God, man, and the world are beyond ridiculous. Then he proceeds to declare that Plato’s and Pythagoras’ are no better. According to the ancient rules of polemics, Chrysostom doesn’t condescend to playing fair; nor does he lift a finger to “steelman”, as some call it today, his noble opponents’ arguments.

On the contrary, he picks the most absurd of the views of Platonism and Pythagoreanism (and what school of thought doesn’t have a handful of those?), such as the state-controlled procreation described in Plato’s Republic, and the Pythagorean belief than human souls can transmigrate into bugs or vegetables. The nail in the coffin of Greek philosophy for Chrysostom (and this is another rhetorical, well-worn commonplace) is the fact that philosophers disagree with each other on almost everything, which means that their views are uncertain.

We would be mistaken, however, to conclude from Chrysostom’s rhetorical fireworks that he is against philosophy as such, or that he advocates instead some simple-minded form of Christianity based on blind faith. His attacks on Pagan schools of philosophy only prove that he is a Greek philosopher to the bone. Anyone familiar with the history of Greek thought will know that, apart from syncretistic, eclectic or synthetic tendencies to combine different schools (increasingly popular in Late Antiquity), the Greeks often relished vicious attacks on other competing schools or even, like the Sceptics, all other schools tout court.

Chrysostom declares triumphantly (if not entirely accurately) that all Pagan philosophy is already extinct and only the true philosophy remains on the battlefield – that is, Christianity. Christianity is not just free from the errors of other schools of philosophy, he argues, but it is also, unlike them, egalitarian. Christian philosophy is clear and accessible, and thanks to the Church “ten thousand nations… have learned to philosophize” (2.5). Not only rich and powerful men who have time for education and leisure, but people of all classes – men, women, and youths alike – can become philosophers.

So exhilarated is Chrysostom by his vision of this perfect philosophy that he is now able to appreciate Plato. Plato is “their chief philosopher”, whose fault is that he didn’t follow the advice of his teacher, Socrates, who said to his judges that he should speak plainly and simply (2.6). However, Chrysostom’s main point is that St John the Evangelist was a poor fisherman from Galilee, which was a country from which nothing good could come, according to the Jews themselves. Since he had no education, all of his wisdom came directly from heaven. He didn’t speak by virtue of his own mind, like Plato, but by virtue of God’s inspiration (2.1). Again, true philosophy is God’s philosophy, not the philosophy laboriously worked out by fallible men.

By the way, it’s worth remembering that fishermen were considered in antiquity to be members of the least trustworthy profession of all.[6] Since the Greeks believed that fishermen were habitual liars, the requirement to trust the witness of a bunch of fishermen must have seemed to the Greeks a very strange way to promote a religion. But for Chrysostom, this is exactly the point which paradoxically strengthens the divine character of Christianity. In a marvellous crescendo of rhetorical exaggeration, Chrysostom comes to a point where St John’s soul was not only incomparably uncouth and primitive due to a perfect storm of poverty, lack of education, and unprivileged geographical location. It also sank down to a subhuman level. Chrysostom exclaims that, through his daily converse with the fishes, St John’s intellect was no better than that of a fish.

Augustine, however, in his celebrated 124 sermons on the Gospel of John (Tractatus in Evangelium Ioannis)[7] took a different path. He didn’t try to emphasize the divine nature of the Prologue by denigrating the Beloved Disciple. For him, he was simply the great Eagle of Christian contemplation and true philosophy, whose prophetic words revealed to all Christians what Plato or Plotinus had arrived at by decades of rigorous and laborious spiritual exercises.

Augustine was definitely right that the first five verses of the Prologue do indeed entirely speak in the language of Greek metaphysics, while only verses 14 and 18 synthesize it with the Incarnation and the historical claims of Christianity. The first lines are simply composed of the key philosophical terms of Greek metaphysics: the first two words, ἐν ἀρχῇ (en archēi, Latin in principio), invoke the beginnings of philosophy, the experience that whatever we encounter in the world of time and change exists because of a timeless, divine Principle (ἀρχή, archē), which philosophers sought from the times of Thales of Miletus (624–547 BC), who claimed that the Principle was water. The expression was read by the commentators not only literally (“in the beginning”), but at a deeper level, as referring to the ultimate Principle, the mysterious Source of reality.

Origen of Alexandria, in the earliest existing commentary on the Gospel of John, identifies God as ἀρχή of all reality, understanding the first verse as claiming that the Son exists in the Father. Also Eriugena understood in principio as “in the Principle”, that is: “in the Father” was the Word (5.15). Chrysostom also wonders why the Father is not mentioned before the Logos, and offers a similar answer: the Father is mentioned by not being mentioned and the reason is that God’s essence is infinite and unknowable (2.8). Chrysostom was doing here nothing other than repeating Plato’s claim in the Republic, developed fully by Plotinus, that the highest Principle is not a being like all the other beings, but is “beyond being/essence” (ἐπέκεινα τῆς οὐσίας, 6.509b) and thus unknowable and ungraspable for the human mind.

For both Chrysostom and Eriugena, the divine darkness and nothing-ness of the “beginning” or “principle” from which the Logos emerges is depicted even at the level of the text itself, since it doesn’t dare name the unnamable, ineffable Father. From the very beginning, then, Chrysostom says, we are drawn beyond all created beings, even above the angels, to look into the infinite abyss of God, which is analogous to a man placed in the midst of a vast sea, whose “eye couldn’t rest on anything, but was brought to boundless contemplation” (οὐ μὴν ἔστησέ τὸ ὄμμα αὐτῷ, ἀλλ᾿ εἰς ἄπειρον ἤγαγε θεωρίαν; 2.9). We simply fall into infinite silence of unknowing.

The use of Logos in the first verse also points to centuries of philosophical tradition, from Heraclitus of Ephesus (6th/5th century BC), who claimed that the ἀρχή of reality was the Logos, through the Stoics who equated God with the Logos, to a Hellenized Jew of Alexandria, Philo (20 BC–AD 50), who claimed not only that God created all things by the Logos, but that Scripture and the best of Greek philosophy can never contradict each other because they reveal the same eternal Truth. The Greek word λόγος (logos) is famously rich in meanings: word, utterance, speech, story, rational argument, explanation, meaning, intelligible structure, thought, reason…

The God proclaimed by the contemplative fisherman from Galilee is Reason and Thought, but it is also Speech. Erasmus, in his famous critical edition of the New Testament (published in 1516) translated the first verse of John as in principio erat sermo and later even published a (rather angry) Apologia de In Principio Erat Sermo (“Defence of In principio erat sermo“). It wasn’t, however, the case that the Greekless medieval philosophers were simply unaware of the ambiguity of the term λόγος.

Thomas Aquinas (1224/5–74), in his meticulously scholarly line-by-line commentary on the Gospel of John,[8] explicitly points out that the Greek term has indeed a double meaning: “thought” and “word” (ratio et verbum, 1.32), which he learnt from Augustine. He wonders why God in His providence allowed the Latins to translate it as verbum, which in Latin means only “word”. The reason is that “the word”, unlike “thought”, refers to an act of speaking, and John describes the divine Logos as that by which all things were made. The Latin verbum, rather than being a testimony to the incapacity of Latin to render the richness of Greek, rightly points out that God is not merely Thought, but He is Thought that is Action, a creative Thought, which expresses itself in everything that exists like our thoughts are expressed in words we speak.

But Aquinas also takes the opportunity to provide a short lecture on his own theory of knowledge, as inspired by the second part of Augustine’s De Trinitate (On the Trinity) and revolving around the concept of the word, verbum, as external and internal. The internal word for Aquinas is not anything linguistic, it is the understanding of reality that is born out of the fertile union of our consciousness with the world we become aware of. In this way, like Augustine, he re-discovers the richness of the Greek Logos, in the apparent poverty of the Latinized Word.

The claim that the Logos is God (θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος, theos ēn ho logos), introduces into the framework of Greek metaphysics the rich and mysterious doctrine of the Trinity, blasphemous and unintelligible not only for Jews and Muslims, but also for conservative Christians philosophers of antiquity, such as Arius and Eunomius, who tried to save the purity of the unknowable and utterly simple Principle by claiming that the Logos is divine or is a god (θεός), but not “the God” (ὁ θεός). For the defenders of the Trinity, like the Cappadocian Fathers, and Augustine, without the identity of the Father and the Logos there is, however, no salvation. Because the Logos assumed our nature, we can participate in His divine nature, and that is the essence of Christianity. But if the Logos is not God, but only the most exalted creature, then the Incarnation is futile, because we cannot be transformed into the real God, the Principle.

From the unknowable God (Jn 1:1), the Prologue proceeds not only towards his self-manifestation as the Trinity (Jn 1:2), but also, in verse three, to His self-manifestation in all reality that is made by Him. How often do we hear today that the Christian God is “up in the sky” or beyond the universe, nowhere to be found among the familiar things of daily life. But for Eriugena, as for Augustine or Chrysostom, or Aquinas, nothing is farther from the truth revealed by the spiritual Eagle. The Irish philosopher was one of the very few people in western Europe who had Greek in the 8th century and he uses his knowledge to point out that χωρὶς αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο οὐδὲ ἕν (Jn 1:3), usually translated as “without it [the Word] not even a single thing has come into being”, should be understood as “outside of it not even a single thing has come into being”. The Greek doesn’t say ἀνεῦ (aneu, “without”), but χωρίς (chōris), which can also mean “outside” (8.20).

Aquinas in his commentary describes this interpretation of χωρίς by Eriugena as “quite beautiful” (satis pulchra, 2.86). God doesn’t create things outside of Himself, and the world doesn’t stand next to God, like a parked car next to a house. Reality is within God and not a single thing is outside of Him. This is not a distant God, but an omnipresent God who is hard to escape. When we wake up on our bed, take a shower and have a cup of tea or coffee in the morning, all of it is inside God and not even the tiniest thing that we experience is outside of Him.

Origen, in his commentary, sees at the very end of Jn 1:3 yet another important theme of Platonic metaphysics. Since without the Logos not even a single thing has come into being, and because the divine Logos cannot be a cause of evil, it follows that evil is nothing, it is “that which doesn’t exist” (Commentary on John, 2.7).[9] This doctrine in its full form will be developed some 30 years later in Rome by Plotinus, who will say that whatever exists insofar as it exists is good, so evil is στέρησις ἀγαθοῦ (sterēsis agathou), the lack or privation of the good (Enneads 1.8). Augustine will absorb this doctrine in AD 386 as the ultimate solution of the problem of evil: it is not a being or “something”, but rather a “no-thing” or privatio boni (“the privation of the good”). He will say in Book 7 of the Confessions: “I inquired what evil is and didn’t find any substance, but a perversity of the will, turning away from the highest substance, that is, from you, God, towards the lowest” (quaesivi quid esset iniquitas et non inveni substantiam, sed a summa substantia, te deo, detortae in infima voluntatis perversitatem, Conf. 7.16.22).

For this metaphysical reading the Latin text of Jn 1:3 is even more suitable: sine ipso factum est nihil, that is, “without It [the Word] nothing was made” – the nihil being here the metaphysical emptiness we call “evil”. Origen is inspired to some degree by Plato, of course, but even more so by the great affirmation of the goodness of existence in the Book of Genesis, where every single thing that God creates is seen by Him as good and all things are seen as very good. Since all is made through the Logos, all is not only good but also rational, and evil is the unintelligible, the irrational, the ultimate meaninglessness, brought into the good world by the fall of angels and men.

Verses 3 and 4 have been translated differently, because these ancient texts didn’t have punctuation, and different punctuation results in different meanings. The majority of ancient and medieval commentaries read: “…without It not even a single thing has come into being. What has come into being, was Life in It, and Life was the Light of men.” This is also the punctuation used by the now standard critical editions of the New Testament: Nestle-Aland’s Novum Testamentum Graecae, 28th edition (NA28) and the Greek New Testament, 5th edition (UBS5). It leads to a puzzle, though. What does it mean that every thing that has come into being is Life?

Chrysostom, in his fifth homily, rejects that reading and suggests instead: “without It not even a single thing has come into being that has come into being. In It was Life, and Life was the Light of men”. In what sense, he asks, is stone Life or is wood Life? They are not even alive, let alone the divine Life itself. Chrysostom is also repudiating anti-Trinitarians who claim that “Life” is the Holy Spirit and that since the Holy Spirit is “in” the Word, it is one of the created things.

But Augustine, famously, offers another interpretation, subsequently followed by Eriugena and Aquinas, which can be found already in Origen (1.22), namely, that here St John teaches the Platonic doctrine of the eternal Forms as archetypes of all the created things existing in the divine Mind. According to Augustine, every single thing that comes into being is a reflection of some aspect of God. It is a standard interpretation of the eternal Forms developed in the Platonism of the first and second centuries (so-called Middle Platonism). The Forms are the objects of God’s self-knowledge, and the essences of all things exist as the objects of the divine Mind. Since God is one and simple, everything that is in God is God. So all things in God are God.

According to this vision, as articulated by thinkers from Origen through Augustine and Eriugena to Aquinas and Dante, all reality is a manifestation of God, a set of mirrors reflecting the divine Face. Eriugena speaks about paradigmata of created things, existing in God as “Life”, and identifies them with the “invisible things of God that are known through the visible things” mentioned by St Paul in his Letter to Romans (1:20–1). This is even more than claming that everything exists and takes place in God. This is to say that everything is alive, alive with God’s own Life, permeated to the tiniest photon and quark by the Logos which is the divine Life. The universe is not an enormous heap of material stuff, as “Science” supposedly proves (of course, it doesn’t prove anything like that, but many people still live mentally in the 19th century, when it did). The universe is filled with Life.

Those who feel instinctively that it simply cannot be true that the universe is devoid of purpose, life, and consciousness, are nowadays often inclined to panpsychism – the doctrine that some form of consciousness exists at all levels of reality, including the subatomic one. Because the understanding of Christian metaphysics has become so distorted in recent centuries, many people are convinced that Christianity teaches that, apart from God and souls, which are conscious, the universe is largely dead and dumb. But in the Prologue to John we have a different, ancient story of a world that is alive and intelligent because it participates in God.

Just as the whole reality of our speech is its meaning, not the pitch or volume of the sounds we make, and that reality exists primarily in our mind and only manifests itself externally in speaking, likewise the whole reality of the world is its meaning too, the Logos, manifesting Itself in creation. Augustine doesn’t embrace panpsychism. He affirms in the first sermon of his Tractatus that St John teaches that “even a stone is life” (et lapis vita est), but then he rejects a crude panpsychism of the Manicheans, according to which “stone has life, and a wall has a soul, and a rope has a soul, and wool, and clothes” (Tract. 1.16).

As Eriugena puts it: “these things which seem to us to lack any capacity to move themselves, are alive in the Word” (quae nobis omni motu carere videntur, in verbo vivunt, 10.5–10). He means the clouds we see every day in the sky, the earth we walk, the water we use to wash our face. Things are not God in themselves and as themselves; but, at the same time, since their most intimate reality is God, they are, in some way, God. Eriugena quotes Dionysius the Areopagite (an anonymous monk living at the beginning of the 6th century AD) in his own Latin translation: “being of all things is Godhead beyond being” (esse omnium est superessentialis divinitas, 10.35) and clarifies: “for in all things that exist, whatever is real, is Himself” (in omnibus enim quae sunt quicquid est, ipse est, 11.20).

If this is true, as the Gospel claims, how is it that we don’t see it? We go through our daily lives as if they were monotonous and flat, filled with ordinary things and mundane chores and personal encounters. But how can anyone or anything be less than wonderful if everything shows God to us at every moment? Augustine answers that divine Life, which is the reality of created things, is the Light of men; and later the Prologue says that it “enlightens every man coming to this world” (Jn 1:9). It means, he says, that, just as in Plotinus’ philosophy, God is lux mentium, the light of our minds, enabling us to be aware and know the contents of our consciousness.

Again, Origen made that claim already: “But the Saviour shines on creatures which have intellect and sovereign reason, that their minds may behold their proper objects of vision” (1.24). Whatever we experience or understand, we experience and understand, so to speak, by God. God is the knowing with which we know, the light in which we see whatever we experience. Not only is the world intelligible in itself, because it’s created by the Logos; when it is known and understood, it is so only by our participation in God’s divine consciousness, in His Light.

And yet, and yet… “It was in the world, and the world was made by It, but the world didn’t know Him” (Jn 1:10). And earlier: “Light shines in darkness and darkness didn’t comprehend It” (Jn 1:5). Augustine interprets this as the description of our fallenness, in which, despite the fact that we are in God, and that every act of our consciousness is naturally grounded in God, we still succeed in persuading ourselves that He doesn’t exist. We are the darkness which cannot understand (comprehendere) what is most obvious. For Origen and Chrysostom, darkness has also another significance: death and sin. The Greek οὐκ κατέλαβεν (ouk katelaben) can mean that darkness “didn’t comprehend” the Light, as the Latin text suggests, but it can also mean “overcome”. The image of the living Light shining in darkness which can never overcome It, becomes a symbolic expression of the Crucifixion and Resurrection, of the triumph of Life over death. Origen uses here the favourite motif of the Greek Fathers, namely, that Crucifixion was a cunning, divine “set up” to defeat Satan, a bait for him to swallow and choke on: “the light sought to lay a snare for the darkness, and waited for it in pursuance of the plan it had formed, then darkness, coming near the light, was brought to an end.” (2.22).

In the Prologue, then, we have all the Christian story condensed, from the Annunciation to Resurrection. It is at the point of Annunciation that “the Word became flesh and dwelt in (and/or among) us” (Jn 1:14). When Mary says “yes”, the Logos assumes human nature in her womb and the head of the ancient Dragon is crushed (Genesis 3:15). The One Ring falls into Mount Doom in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings on 25 March, because on this day the Catholic Church celebrates the Annunciation and the “inhumanising” (ἐνανθρώπωσις, enanthrōpōsis).

Augustine beautifully states that the unique or only-begotten Son (unicus), has come down to us, because he didn’t want to remain unicus, the only Son. He wanted there to be countless sons of God, who are God by grace like He is God by nature. The Logos descends and becomes Man in order to ascend to God taking with Him all those who freely choose to believe “in His name” (Jn 1:12), that is, in what He is: God and Man, and thus capable of giving men the power (ἔδωκεν ἐξουσίαν, edōken exousiān) to become God. As Eriugena says: “He makes gods of men, who made God man” (de hominibus facit deos qui de deo fecit hominem, 21.25).

The Prologue to John remains one of the key texts of Western civilization, not only for Christians. Even if scholars wouldn’t agree with Augustine’s astonishing claim that it says “exactly the same thing” (hoc idem omnino) as the writings of Plotinus and other Pagan Platonists, it has sealed the marriage between Christian revelation and Platonic metaphysics, which gave rise to the emergence of the medieval university, the Renaissance and early-modern natural science. For Augustine, it contains the entire Truth that people need to hear from religion and philosophy, as well as the promised gift of divine power to transform their life. For Chrysostom, the very act of listening to the Prologue’s words is transformative: those who hear and receive them grow wings like eagles and are able to fly to heaven. More than that, they become equal to angels (2.1-2, 7).

The Prologue invites readers to contemplate the poverty of the traditional Nativity Stable together with the most fundamental metaphysical truths, universal to all mankind. It teaches us to see in that crowded space, filled with animals, shepherds, the Magi, and the Family, nothing less than heaven: “We enter heaven when we enter here; not in place, I mean, but in disposition; for it is possible for one who is on earth to stand in heaven, and to have vision of the things that are there, and to hear the words from thence” (John Chrysostom, Commentary on John, 2.10). C.S. Lewis points out in the final instalment of his Narnia stories, The Last Battle (1956), through the mouth of Professor Digory, that in the case of all true things the inside is always bigger than the outside. To this Lucy responds, in the spirit of the Prologue:

“In our world too, a Stable once had something inside it that was bigger than our whole world.”

Mateusz Stróżyński is a Classicist, philosopher, psychologist, and psychotherapist, working as an Associate Professor in the Institute of Classical Philology at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. He is interested in ancient philosophy, especially the Platonic tradition. His new book Plotinus on the Contemplation of the Intelligible World is forthcoming through Cambridge University Press.

Notes

| ⇧1 | The Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus, writes about John the Baptist as a virtuous man and moral teacher, who had great influence on the crowds (Antiquitates Iudaicae 18.116-17). |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | The critical edition of the Latin text is Jean Scot, Homélie sur le prologue de Jean, É. Jeauneau (ed.) (Sources Chrétiennes 151, Paris 1969); the English translation can be found in O.Davies (ed.), Celtic Spirituality (New York, 1999) 411-32. |

| ⇧3 | Conf. 7.9.13. See J.J.O’Donnell’s electronic edition here. |

| ⇧4 | The essay was based on a 1981 lecture at the University of Missouri and published in The Missouri Review 5.3 (1982) 117–28. |

| ⇧5 | The Greek text is found in in Migne’s Patrologia Graeca 59; the English translation, based on Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series 14, is available here. |

| ⇧6 | I owe this piece of information about a shamelessly bigoted attitude of the ancients to Krystyna Bartol’s excellent introduction to her Polish translation of Oppian’s Halieutica. |

| ⇧7 | The Latin text can be found here. |

| ⇧8 | The Latin text, with the English translation of J. Weisheipl and F. Larcher, is available here. |

| ⇧9 | What survives of this commentary is translated from Greek by A. Menzies in Ante-Nicene Fathers 9, available here. |