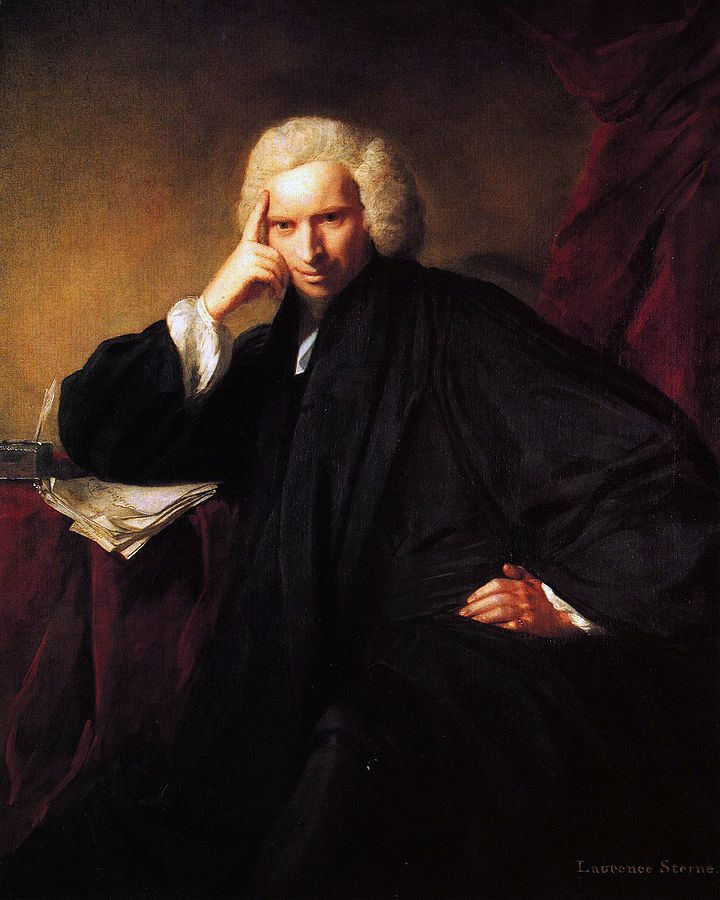

Mark Walker

Laurence Sterne (1713–68) would have loved Monty Python. The linguistic dexterity and the faux erudition, the silliness and the surreal, the unrepentantly puerile fixation on farting, boobs and smut. It was all very much in Sterne’s wheelhouse. The author of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, one of the greatest not to say silliest and bawdiest comic novels in the English language, had been there and done all of that two centuries earlier.

One joke he would certainly have relished is the “Romanes eunt domus” scene from the Life of the Brian, in which John Cleese’s pedantic centurion gives hapless Brian a lesson in Latin grammar (“Go home? This is motion towards isn’t it boy?”). Sterne was primus sine paribus, first without equal, in comical Latin. Peppered throughout Tristam Shandy are Latin tags and gags galore. Unlike Python, however, Sterne expected his readers to get the joke right away: when a scholarly work called De fartandi et illlustrandi fallaciis (Vol. 3, Preface) is mentioned he doesn’t need to translate it (“On the deceptions of farting and illustration”).

When he introduces the “filthy and obscene treatise de Concubinis retinendis” by Phutatorius (Vol. 4, ch. 27) he does not need to explain that it’s about how to keep a mistress, nor that the author’s name is likely a play on the Latin verb futuo (“I f**k”). Elsewhere in a list of logical arguments he gives us, among others, the Argumentum Fistulatorium (the argument of a player on the pipe), the Argumentum ad Crumenam (the argument to the purse) and the Argumentum Tripodium (the three-legged argument) (Vol. 1, ch. 11). A nose (more on noses later!) is ad mensuram suam legitimam (at its proper size), while another is ad excitandum focum (suitable for stirring up the fire) (Vol. 3, chs. 27–8).

There are, however, two chapters in Tristram Shandy in which Latin has a much greater part to play than passing facetiae (witticisms). The first is his printing of a lengthy passage from the Textus de Ecclesia Roffensi, per Ernulfum Episcopum, the “Tome of Rochester”, a collection of documents relating to the church of Rochester compiled by Bishop Ernulf between 1122 and 1124. The extract comes after Dr Slop has cut his thumb attempting to undo a knot and is swearing at the servant Obadiah. Tristram’s father reaches for a list of curses suitable to the occasion and hands Slop this chapter on excommunication:

“If I remember right, ‘tis too violent for a cut of the thumb. – Not at all, quoth Dr Slop – the devil take the fellow. – Then answered my father, ‘Tis much at your service.” (Vol. 3, ch. 10)

The text that follows is an astonishingly detailed account of what will happen to anyone excommunicated by the medieval church, the point of which seems to be to make Dr Slop (a Catholic) extremely uncomfortable, as he is made to read it aloud to Tristram’s father and uncle Toby. For the staunch anti-Catholic, Church of England cleric Sterne this is a reductio ad absurdum of Catholic doctrine. For modern readers, the whole thing seems more silly than satire, as every prophet, saint and martyr is invoked to curse the malefactor in every possible way and in every conceivable act and part of his body. The emphasis on bodily parts and bodily functions must have tickled Sterne’s sense of humour:

Maledictus sit vivendo, moriendo … quiescendo, mingendo, cacando, flebotomando.

“May he be cursed in living, in dying … in resting, in pissing, in shitting, and in blood-letting.”

(The full Latin text is given with translation in Appendix I below.)

The absurdity is heightened when we recall that the malefactor is poor Obadiah, whose unforgivable sin was to tie a knot so tight that Dr Slop cut his thumb trying to loosen it:

Maledictus sit in totis viribus corporis. Maledictus sit intus et exterius … in totis compagibus membrorum, a vertice capitis, usque ad plantam pedis

“May he be cursed in all the faculties of his body, may he be cursed inwardly and outwardly… in all the joints and articulations of his members, from the top of his head to the sole of his foot.”

This ridiculously lengthy imprecation contrasts pointedly with the simple compassion of uncle Toby after he has heard it:

“I declare, quoth my uncle Toby, my heart would not let me curse the devil himself with so much bitterness. – He is the father of curses, replied Dr Slop. – So am not I, replied my uncle. – But he is cursed and damned already, to all eternity. – replied Dr Slop.

I am sorry for it, quoth my uncle Toby.” (Vol. 3, ch. 11)

The second extensive passage of Latin in the novel is one of Sterne’s own creation. Opening Volume 4 is what purports to be an extract from a learned treatise on noses, De Nasis, by the renowned German scholar Hafan Slawkenbergius. Both scholar and book are, naturally, fictions invented by Sterne in order to poke fun at, as Sterne himself remarked, “those learned blockheads who, in all ages, have wasted their time and much learning upon points as foolish.”[1]

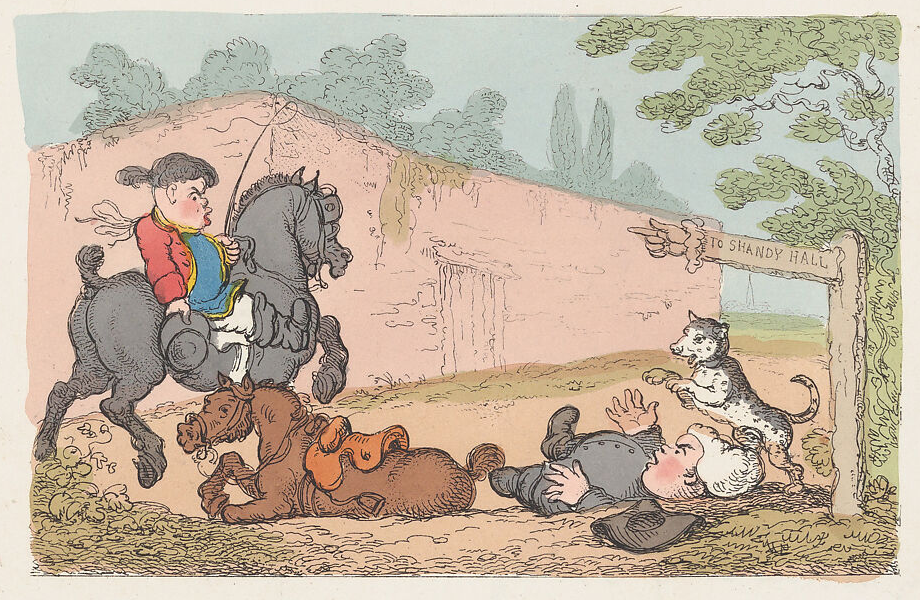

We are (un)reliably informed that the second book of Slawkenebergius’ nasal treatise consists of a series of stories illustrative of different types of noses. Sterne gives us one of these, a meandering tale in Don Quixote fashion about a mysterious traveller with an extraordinarily long nose who rides into Strasburg one day and causes all manner of commotions, especially among the ladies of the town.

In typical Shandean fashion, the prominent nose stands proxy for another long, hard appendage of the male anatomy. The author drives home the point (see what I did there?) at the beginning of the story with an innuendo worthy of generations of sniggering schoolboys – a play on the Latin word for scabbard. Seeing the traveller waving his naked sword (nudam acinacem), the guard (miles) at the town gate expresses sadness that such “a courteous soul” (virum urbanum) has lost his scabbard (vaginam) and remarks that he will not “get a scabbard to fit it in all Strasburg”:

Dolet mihi, ait miles… virum adeo urbanum vaginam perdidisse: itinerari haud poterit nudâ acinaci; neque vaginam toto Argentorato habilem inveniet.

“It grieves me, said the sentinel… that so courteous a soul should have lost his scabbard—he cannot travel without one to his scymetar, and will not be able to get a scabbard to fit it in all Strasburg.”

(The full Latin text is given with translation in Appendix II below.)

Then the stranger’s ‘nose’ sparks animated debates in the town, notably between husbands and their wives, about its genuineness. First, a trumpeter and his wife:

Quantus nasus! aeque longus est, ait tubicina, ac tuba.

Et ex eodem metallo, ait tubicen, velut sternutamento audias.

Tantum abest, respondit illa, quod fistulam dulcedine vincit.

Æneus est, ait tubicen.

Nequaquam, respondit uxor.

Rursum affirmo, ait tubicen, quod aeneus est.

Rem penitus explorabo; prius, enim digito tangam, ait uxor, quam

dormivero.

“Benedicity!—What a nose! ’tis as long, said the trumpeter’s wife, as a trumpet.

And of the same mettle, said the trumpeter, as you hear by its sneezing.

—’Tis as soft as a flute, said she.

—’Tis brass, said the trumpeter.

—’Tis a pudding’s end—said his wife.

I tell thee again, said the trumpeter, ’tis a brazen nose.

I’ll know the bottom of it, said the trumpeter’s wife, for I will touch it with my finger before I sleep.”

Then another couple, the innkeeper and his wife – once again, it is the wife who insists she must touch it:

Per sanctos sanctasque omnes, ait hospitis uxor, nasis duodecim maximis in toto Argentorato major est!—estne, ait illa mariti in aurem insusurrans, nonne est nasus praegrandis?

Dolus inest, anime mi, ait hospes—nasus est falsus.

Verus est, respondit uxor—

Ex abiete factus est, ait ille, terebinthinum olet—

Carbunculus inest, ait uxor.

Mortuus est nasus, respondit hospes.

Vivus est ait illa,—et si ipsa vivam tangam.

“By saint Radagunda, said the inn-keeper’s wife to herself, there is more of it than in any dozen of the largest noses put together in all Strasburg! is it not, said she, whispering her husband in his ear, is it not a noble nose?

‘Tis an imposture, my dear, said the master of the inn—’tis a false nose.—

‘Tis a true nose, said his wife.—

‘Tis made of fir-tree, said he,—I smell the turpentine.—

There’s a pimple on it, said she.

‘Tis a dead nose, replied the inn-keeper.

‘Tis a live nose, and if I am alive myself, said the inn-keeper’s wife, I will touch it.”

At the end of this Latin section, which is only the beginning of the story, we get a fascinating premonition of the ‘prophet’ scene in Life of Brian. In the Python movie, Brian is forced to make an impromptu speech as he’s trying to elude the Romans. But as soon as the soldiers have passed on, he breaks off his lecture and leaves. His audience, left hanging, quickly split into factions (“Follow the gourd! No! let us gather shoes!”) and start to condemn each other as schismatics and heretics. Sterne’s stranger likewise promises his nose shall never be touched until a certain hour (usque ad illam horam – ). Which hour (quam horam?) asks the innkeeper’s wife, becoming increasingly desperate to know. But the stranger mounts his mule and leaves without replying:

Minimo tangetur, inquit ille (manibus in pectus compositis) usque ad illam horam——Quam horam? ait illa——Nullam, respondit peregrinus, donec pervenio ad—Quem locum, obsecro? ait illa——Peregrinus nil respondens mulo conscenso discessit.

“It never shall be touched, said he, clasping his hands and bringing them close to his breast, till that hour.—What hour? cried the inn-keeper’s wife.—Never!—never! said the stranger, never tell I am got—For heaven sake into what place? said she.—The stranger rode away without saying a word.”

The townspeople split into religious factions regarding the true nature of the nose. And although the stranger has promised to return, he never does. People, says Slawkenbergius (i.e. Sterne) at the end, would be much better off if instead of following the stranger’s nose, “each man followed his own.”

In both examples above the use of an extended passage of Latin imparts a faux gravitas to these inconsequential episodes, inflating them far beyond their actual importance. In the case of Bishop Ernulf’s excommunication curses, Sterne as a clergyman was probably familiar with the text from its 1681 reprint in a pamphlet titled The Pope’s Dreadful Curse.[2] It was at that time presented as an example of what English Protestants could expect from their Catholic contemporaries. In Sterne’s hands, it becomes a pompous absurdity.[3]

In the second, Sterne gives us some of his own Latin, which is a rather loose translation of the English, rather than vice versa as the novel claims. Aside from an excuse to make that smutty scabbard/vagina joke, the Latin exists here to elevate the supposed academic credentials of the story, since anything written in Latin must ipso facto be serious and deserving of attention. In fact, the Latin is anything but, being nothing more than a transcription of superficial descriptions and desultory conversations, double-entendres included. At one point, Sterne drops into Greek, adding yet another layer of fake academic camouflage. The traveller takes his clothes out of his bag (manticam):

Peregrinus mulo descendens stabulo includi, et manticam inferri jussit: quâ apertâ et coccineis sericis femoralibus extractis cum argento laciniato περιζώματε, his sese induit, statimque, acinaci in manu, ad forum deambulavit.

“The moment the stranger alighted, he ordered his mule to be led into the stable, and his cloak-bag to be brought in; then opening, and taking out of it, his crimson-sattin breeches, with a silver-fringed—(appendage to them, which I dare not translate)—he put his breeches, with his fringed cod-piece on, and forthwith with his short scymetar in his hand, walked out to the grand parade.”

The Greek περίζωμα (“loincloth”) here stands in for a pair of frilly silver undies – the bashful Slawkenbergius being too embarrassed to write the word in learned Latin instead resorts to the even-more-learned Greek![4]

Away from fiction, Sterne also used Latin in one of his letters. Sitting in a London coffee house where it was so noisy he could hardly think, he wrote to his rakish friend John Hall-Stevenson in December 1767:

scribo hanc epistolam in domo coffeatariâ et plenâ sociorum strepitosorum, qui non permittent me cogitare unam cogitationem.

“I am writing this letter in a coffee-house full of noisy company, who will not permit me to think a single thought.”

(The full Latin text is given with translation in Appendix III below.)

The reason for the change of language becomes clearer when Sterne writes (in dog Latin):

Nescio quid est materia cum me, sed sum fatigatus et aegrotus de meâ uxore plus quam unquam…

“I don’t know what’s the matter with me, but I am more sick and tired of my wife than ever.”

It seems that Sterne didn’t want this letter being read by prying eyes, especially those of his wife! His painfully literal rendering of “I don’t know what’s the matter with me” would doubtless have puzzled Cicero, but it surely would have made Hall-Stevenson chuckle. And how he must have laughed when he read this:

nam diabolus iste qui me intravit, non est diabolus vanus, aut consobrinus suus Lucifer – sed est diabolus amabundus, qui non vult sinere me esse solum; nam cum non cumbendo cum uxore meâ, sum mentulatior quàm par est.

“For that devil who has entered me, is not an idle devil, or Lucifer his cousin – but he is a sexy devil, who does not allow me to be alone; for since I am not sleeping with my wife, I am hornier than usual.”

Sterne uses some colourful non-Classical words here: amabundus (“full of love”, “sexy”) and cumbendo (“sleeping”). But the word that really stands out is his coining of the term mentulatior – the comparative form of mentulatus, literally “having a penis” – suggesting a very Shandean pun, “more cocky than usual”.

In his relentless mocking of erudition for its own sake, Sterne weaponizes Latin. His often trivial and occasionally absurd use of this supposedly elevated language thumbs its nose at all those scholarly treatises and religious tracts whose paucity of thought is hidden behind the learned screen of Latin. In Sterne’s hands Latin becomes a prick (perfect Shandean innuendo!) to burst the balloon of pomposity.

Mark Walker is currently Head of Classics at The Beacon School in Amersham. In his previous life, when ‘spare time’ was a thing, he penned a few non-academic books about Latin, including Annus Horribilis: Latin for Everyday Life and Britannica Latina: 2000 Years of British Latin. For some reason that now escapes him, he also thought it might be fun to translate The Hobbit into Latin as Hobbitus Ille (it wasn’t) and Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Vita Merlini into English as The Life of Merlin: A New Verse Translation. He was also the founder and editor of Vates: The Journal of New Latin Poetry, which almost-but-not-quite made a modest impression in certain exclusive circles.

Appendix I

Textus de Ecclesiâ Roffensi, per Ernulfum Episcopum.

Cap. XXV. EXCOMMUNICATIO

Ex auctoritate Dei omnipotentis, Patris, et Filij, et Spiritus Sancti, et sanctorum canonum, sanctæque et intermeratæ Virginis Dei genetricis Mariæ, —Atque omnium coelestium virtutum, angelorum, archangelorum, thronorum, dominationum, potestatuum, cherubin ac seraphin, & sanctorum patriarchum, prophetarum, & omnium apostolorum et evangelistarum, & sanctorum innocentum, qui in conspectu Agni soli digni inventi sunt canticum cantare novum, et sanctorum martyrum, et sanctorum confessorum, et sanctarum virginum, atque omnium simul sanctorum et electorum Dei,—Excommunicamus, et anathematizamus vel oshunc sfurem, vel vel oshunc smalefactorem, N. N. et a liminibus sanctæ Dei ecclesiæ sequestramus et æternis suppliciis vel iexcruciandus, nmancipetur, cum Dathan et Abiram, et cum his qui dixerunt Domino Deo, Recede à nobis, scientiam viarum tuarum nolumus: et sicut aquâ ignis extinguitur, sic extinguatur vel eorumlucerna ejus in secula seculorum nisi respuerit, et ad satisfactionem nvenerit. Amen. Maledicat osillum Deus Pater qui hominem creavit. Maledicat osillum Dei Filius qui pro homine passus est. Maledicat osillum Spiritus Sanctus qui in baptismo effusus est. Maledicat osillum os sancta crux, quam Christus pro nostrâ salute hostem triumphans, ascendit.

Maledicat osillum sancta Dei genetrix et perpetua Virgo Maria. Maledicat osillum sanctus Michael, animarum susceptor sacrarum. Maledicant osillum omnes angeli et archangeli, principatus et potestates, omnisque militia coelestis.

Maledicat osillum patriarcharum et prophetarum laudabilis numerus. Maledicat osillum sanctus Johannes præcursor et Baptista Christi, et sanctus Petrus, et sanctus Paulus, atque sanctus Andreas, omnesque Christi apostoli, simul et cæteri discipuli, quatuor quoque evangelistæ, qui sua prædicatione mundum universum converterunt. Maledicat osillum cuneus martyrum et confessorum mirisicus, qui Deo bonis operibus placitus inventus est.

Maledicant osillum sacrarum virginum chori, quæ mundi vana causa honoris Christi respuenda contempserunt. Maledicant osillum omnes sancti qui ab initio mundi usque in sinem seculi Deo dilecti inveniuntur.

Maledicant osillum coeli et terra, et omnia sancta in eis manentia.

Maledictus nsit ubicunque nfuerit, sive in domo, sive in agro, sive in viâ, sive in semitâ, sive in silvâ, sive in aquâ, sive in ecclesiâ.

Maledictus sit vivendo, moriendo, — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — manducando, bibendo, esuriendo, sitiendo, jejunando, dormitando, dormiendo, vigilando, ambulando, stando, sedendo, jacendo, operando, quiescendo, mingendo, cacando, flebotomando.

iMaledictus nsit in totis viribus corporis.

Maledictus sit intus et exterius.

Maledictus sit in capillis; maledictus sit in cerebro. Maledictus sit in vertice, in temporibus, in fronte, in auriculis, in superciliis, in oculis, in genis, in maxillis, in naribus, in dentibus, mordacibus, in labris sive molibus, in labiis, in guttere, in humeris, in harnis, in brachiis, in manubus, in digitis, in pectore, in corde, et in omnibus interioribus stomacho tenus, in renibus, in inguinibus, in femore, in genitalibus, in coxis, in genubus, in cruribus, in pedibus, et in unguibus.

Maledictus sit in totis compagibus membrorum, a vertice capitis, usque ad plantam pedis—non sit in eo sanitas.

Maledicat illum Christus Filius Dei vivi toto suæ majestatis imperio—et insurgat adversus illum coelum cum omnibus virtutibus quæ in eo moventur ad damnandum eum, nisi penituerit et ad satisfactionem venerit. Amen. Fiat, fiat. Amen.

BY the authority of God Almighty, the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and of the holy canons, and of the undefiled Virgin Mary, mother and patroness of our Saviour.” I think there is no necessity, quoth Dr. Slop, dropping the paper down to his knee, and addressing himself to my father,—as you have read it over, Sir, so lately, to read it aloud;—and as Captain Shandy seems to have no great inclination to hear it,—I may as well read it to myself. That’s contrary to treaty, replied my father,—besides, there is something so whimsical, especially in the latter part of it, I should grieve to lose the pleasure of a second reading. Dr. Slop did not altogether like it,—but my uncle Toby offering at that instant to give over whistling, and read it himself to them;—Dr. Slop thought he might as well read it under the cover of my uncle Toby’s whistling,—as suffer my uncle Toby to read it alone;—so raising up the paper to his face, and holding it quite parallel to it, in order to hide his chagrin,—he read it aloud as follows,—my uncle Toby whistling Lillabullero, though not quite so loud as before.

“By the authority of God Almighty, the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and of the undefiled Virgin Mary, mother and patroness of our Saviour, and of all the celestial virtues, angels, arch-angels, thrones, dominions, powers, cherubins and seraphins, and of all the holy patriarchs, prophets, and of all the apostles and evangelists, and of the holy innocents, who in the sight of the holy Lamb, are found worthy to sing the new song of the holy martyrs and holy confessors, and of the holy virgins, and of all the saints together, with the holy and elect of God.—May he,” (Obadiah) “be damn’d,” (for tying these knots.)—”We excommunicate, and anathematise him, and from the thresholds of the holy church of God Almighty we sequester him, that he may be tormented, disposed and delivered over with Dathan and Abiram, and with those who say unto the Lord God, Depart from us, we desire none of thy ways. And as fire is quenched with water, so let the light of him be put out for evermore, unless it shall repent him” (Obadiah, of the knots which he has tied) “and make satisfaction” (for them.) Amen.

“May the Father who created man, curse him.—May the Son who suffered for us, curse him.—May the Holy Ghost who was given to us in baptism, curse him (Obadiah.)—May the holy cross which Christ for our salvation triumphing over his enemies, ascended,—curse him.

May the holy and eternal Virgin Mary, mother of God, curse him.—May St. Michael the advocate of holy souls, curse him.—May all the angels and archangels, principalities and powers, and all the heavenly armies, curse him.” [Our armies swore terribly in Flanders, cried my uncle Toby,—but nothing to this.—For my own part, I could not have a heart to curse my dog so.]

“May St. John the præ-cursor, and St. John the Baptist, and St. Peter and St. Paul, and St. Andrew, and all other Christ’s apostles, together curse him. And may the rest of his disciples and four evangelists, who by their preaching converted the universal world,—and may the holy and wonderful company of martyrs and confessors, who by their holy works are found pleasing to God Almighty, curse him (Obadiah.)

“May the holy choir of the holy virgins, who for the honour of Christ have despised the things of the world, damn him.—May all the saints who from the beginning of the world to everlasting ages are found to be beloved of God, damn him.—May the heavens and earth, and all the holy things remaining therein, damn him,” (Obadiah) “or her,” (or whoever else had a hand in tying these knots.)

“May he (Obadiah) be damn’d where-ever he be,—whether in the house or the stables, the garden or the field, or the highway, or in the path, or in the wood, or in the water, or in the church.—May he be cursed in living, in dying.” [Here my uncle Toby taking the advantage of a minim in the second barr of his tune, kept whistling one continual note to the end of the sentence—Dr. Slop with his division of curses moving under him, like a running bass all the way.] “May he be cursed in eating and drinking, in being hungry, in being thirsty, in fasting, in sleeping, in slumbering, in walking, in standing, in sitting, in lying, in working, in resting, in pissing, in shitting, and in blood-letting.”

“May he (Obadiah) be cursed in all the faculties of his body.

May he be cursed inwardly and outwardly.—May he be cursed in the hair of his head.—May he be cursed in his brains, and in his vertex,” (that is a sad curse, quoth my father) “in his temples, in his forehead, in his ears, in his eye-brows, in his cheeks, in his jaw-bones, in his nostrils, in his foreteeth and grinders, in his lips, in his throat, in his shoulders, in his wrists, in his arms, in his hands, in his fingers.

May he be damn’d in his mouth, in his breast, in his heart and purtenance, down to the very stomach.

“May he be cursed in his reins, and in his groin,” (God in heaven forbid, quoth my uncle Toby)—”in his thighs, in his genitals,” (my father shook his head) “and in his hips, and in his knees, his legs, and feet, and toe-nails.

“May he be cursed in all the joints and articulations of his members, from the top of his head to the soal of his foot, may there be no soundness in him.

“May the Son of the living God, with all the glory of his Majesty”—[Here my uncle Toby throwing back his head, gave a monstrous, long, loud Whew—w—w—something betwixt the interjectional whistle of Hey day! and the word itself.⸻

—By the golden beard of Jupiter—and of Juno, (if her majesty wore one), and by the beards of the rest of your heathen worships, which by the bye was no small number, since what with the beards of your celestial gods, and gods aerial and acquatick,—to say nothing of the beards of town-gods and country-gods, or of the celestial goddesses your wives, or of the infernal goddesses your whores and concubines, (that is in case they wore ’em)—all which beards, as Varro tells me, upon his word and honour, when mustered up together, made no less than thirty thousand effective beards upon the pagan establishment;—every beard of which claimed the rights and privileges of being stroked and sworn by,—by all these beards together then,—I vow and protest, that of the two bad cassocks I am worth in the world, I would have given the better of them, as freely as ever Cid Hamet offered his,—only to have stood by, and heard my uncle Toby’s accompanyment.]

—”Curse him,”—continued Dr. Slop,—”and may heaven with all the powers which move therein, rise up against him, curse and damn him (Obadiah) unless he repent and make satisfaction. Amen, so be it,—so be it. Amen.”

Appendix II

SLAWKENBERGII FABELLA

Vespera quâdam frigidulâ, posteriori in parte mensis Augusti, peregrinus, mulo susco colore insidens, manticâ a tergo, paucis indusijs, binis calceis, braccisque sericis coccinejs repletâ, Argentoratum ingressus est.

Militi eum percontanti, quum portus intraret dixit, se apud Nasorum promontorium fuisse, Francofurtum proficisci, et Argentoratum, transitu ad fines Sarmatiæ mensis intervallo, reversurum.

Miles peregrini in faciem suspexit—Di boni, nova forma nasi!

At multum mihi profuit, inquit peregrinus, carpum amento extrabens, e quo pependit acinaces: Loculo manum inseruit; & magnâ cum urbanitate, pilei parte anteriore tactâ manu sinistrâ, ut extendit dextram, militi florinum dedit et processit.

Dolet mihi, ait miles, tympanistam nanum et valgum alloquens, virum adeo urbanum vaginam perdidisse; itinerari haud poterit nudâ acinaci, neque vaginam toto Argentorato, habilem inveniet.—Nullam unquam habui, respondit peregrinus respiciens,—seque comiter inclinans—hoc more gesto, nudam acinacem elevans, mulo lentò progrediente, ut nasum tueri possim.

Non immerito, benigne peregrine, respondit miles.

Nihili æstimo, ait ille tympanista, e pergamenâ factitius est.

Prout christianus sum, inquit miles, nasus ille, ni sexties major sit, meo esset conformis.

Crepitare audivi ait tympanista.

Mehercule! sanguinem emisit, respondit miles.

Miseret me, inquit tympanista, qui non ambo titigimus!

Eodem temporis puncto, quo hæc res argumentata fuit inter militem et tympanistam, disceptabatur ibidem tubicine & uxore suâ, qui tunc accesserunt, et peregrino prætereunte, restiterunt.

Quantus nasus! æque longus est, ait tubicina, ac tuba.

Et ex eodem metallo, ait tubicen, velut sternutamento audias.

Tantum abest, respondit illa, quod fistulam dulcedine vincit.

Æneus est, ait tubicen.

Nequaquam, respondit uxor.

Rursum affirmo, ait tubicen, quod æneus est.

Rem penitus explorabo; prius, enim digito tangam, ait uxor, quam dormivero.

Mulus peregrini, gradu lento progressus est, ut unumquodque verbum controversiæ, non tantum inter militem et tympanistam, verum etiam inter tubicinem et uxorem ejus, audiret.

Nequaquam, ait ille, in muli collum fræna demittens, & manibus ambabus in pectus positis, (mulo lentè progrediente) nequaquam ait ille, respiciens, non necesse est ut res isthæc dilucidata foret. Minime gentium! meus nasus nunquam tangetur, dum spiritus hos reget artus—ad quid agendum? ait uxor burgomagistri.

Peregrinus illi non respondit. Votum faciebat tunc temporis sancto Nicolao, quo facto, sinum dextram inserens, e quâ negligenter pependit acinaces, lento gradu processit per plateam Argentorati latam quæ ad diversorium templo ex adversum ducit.

Peregrinus mulo descendens stabulo includi, & manticam inferri jussit: quâ apertâ et coccineis sericis femoralibus extractis cum argenteo laciniato Περιζοματὲ, his sese induit, statimque, acinaci in manu, ad forum deambulavit.

Quod ubi peregrinus esset ingressus, uxorem tubicinis obviam euntem aspicit; illico cursum flectit, metuens ne nasus suus exploraretur, atque ad diversorium regressus est—exuit se vestibus; braccas coccineas sericas manticæ imposuit mulumque educi jussit.

Francofurtum proficiscor, ait ille, et Argentoratum quatuor abhinc hebdomadis revertar.

Bene curasti hoc jumentum (ait) muli faciem manu demulcens—me, manticamque meam, plus sexcentis mille passibus portavit.

Longa via est! respondet hospes, nisi plurimum esset negoti.—Enimvero ait peregrinus a nasorum promontorio redij, et nasum speciosissimum, egregiosissimumque quem unquam quisquam sortitus est, acquisivi?

Dum peregrinus hanc miram rationem, de seipso reddit, hospes et uxor ejus, oculis intentis, peregrini nasum contemplantur—Per sanctos, sanctasque omnes, ait hospitis uxor, nasis duodecim maximis, in toto Argentorato major est!—estne ait illa mariti in aurem insusurrans, nonne est nasus prægrandis?

Dolus inest, anime mi, ait hospes—nasus est falsus.—

Verus est, respondit uxor.—

Ex abiete factus est, ait ille, terebinthinum olet—

Carbunculus inest, ait uxor.

Mortuus est nasus, respondit hospes.

Vivus est, ait illa,—& si ipsa vivam tangam.

Votum seci sancto Nicolao, ait peregrinus, nasum meum intactum fore usque ad—Quodnam tempus? illico respondit illa.

Minime tangetur, inquit ille (manibus in pectus compositis) usque ad illam horam—Quam horam? ait illa.—Nullam, respondit peregrinus, donec perveneo, ad—Quem locum,—obsecro? ait illa—Peregrinus nil respondens mulo conscenso discessit.

Volume IV: SLAWKENBERGIUS’S TALE

IT was one cool refreshing evening, at the close of a very sultry day, in the latter end of the month of August, when a stranger, mounted upon a dark mule, with a small cloak-bag behind him, containing a few shirts, a pair of shoes, and a crimson-sattin pair of breeches, entered the town of Strasburg.

He told the sentinel, who questioned him as he entered the gates, that he had been at the promontory of Noses—was going on to Frankfort—and should be back again at Strasburg that day month, in his way to the borders of Crim-Tartary.

The sentinel looked up into the stranger’s face—never saw such a nose in his life!

—I have made a very good venture of it, quoth the stranger—so slipping his wrist out of the loop of a black ribban, to which a short scymetar was hung: He put his hand into his pocket, and with great courtesy touching the forepart of his cap with his left-hand, as he extended his right—he put a florin into the sentinel’s hand, and passed on.

It grieves me, said the sentinel, speaking to a little dwarfish bandy-legg’d drummer, that so courteous a soul should have lost his scabbard—he cannot travel without one to his scymetar, and will not be able to get a scabbard to fit it in all Strasburg.—I never had one, replied the stranger, looking back to the sentinel, and putting his hand up to his cap as he spoke—I carry it, continued he thus—holding up his naked scymetar, his mule moving on slowly all the time, on purpose to defend my nose.

It is well worth it, gentle stranger, replied the sentinel.

—’Tis not worth a single stiver, said the bandy-leg’d drummer—’tis a nose of parchment.

As I am a true catholic—except that it is six times as big—’tis a nose, said the sentinel, like my own.

—I heard it crackle, said the drummer.

By dunder, said the sentinel, I saw it bleed.

What a pity, cried the bandy-legg’d drummer, we did not both touch it!

At the very time that this dispute was maintaining by the sentinel and the drummer—was the same point debating betwixt a trumpeter and a trumpeter’s wife, who were just then coming up, and had stopped to see the stranger pass by.

Benedicity!—What a nose! ’tis as long, said the trumpeter’s wife, as a trumpet.

And of the same mettle, said the trumpeter, as you hear by its sneezing.

—’Tis as soft as a flute, said she.

—’Tis brass, said the trumpeter.

—’Tis a pudding’s end—said his wife.

I tell thee again, said the trumpeter, ’tis a brazen nose.

I’ll know the bottom of it, said the trumpeter’s wife, for I will touch it with my finger before I sleep.

The stranger’s mule moved on at so slow a rate, that he heard every word of the dispute, not only betwixt the sentinel and the drummer; but betwixt the trumpeter and the trumpeter’s wife.

No! said he, dropping his reins upon his mule’s neck, and laying both his hands upon his breast, the one over the other in a saint-like position (his mule going on easily all the time) No! said he, looking up,—I am not such a debtor to the world—slandered and disappointed as I have been—as to give it that conviction—no! said he, my nose shall never be touched whilst heaven gives me strength—To do what? said a burgomaster’s wife.

The stranger took no notice of the burgomaster’s wife—he was making a vow to saint Nicolas; which done, having uncrossed his arms with the same solemnity with which he crossed them, he took up the reins of his bridle with his left hand, and putting his right-hand into his bosom, with his scymetar hanging loosely to the wrist of it, he rode on as slowly as one foot of the mule could follow another thro’ the principal streets of Strasburg, till chance brought him to the great inn in the market-place over-against the church.

The moment the stranger alighted, he ordered his mule to be led into the stable, and his cloak-bag to be brought in; then opening, and taking out of it, his crimson-sattin breeches, with a silver-fringed—(appendage to them, which I dare not translate)—he put his breeches, with his fringed cod-piece on, and forthwith with his short scymetar in his hand, walked out to the grand parade.

The stranger had just taken three turns upon the parade, when he perceived the trumpeter’s wife at the opposite side of it—so turning short, in pain lest his nose should be attempted, he instantly went back to his inn—undressed himself, packed up his crimson-sattin breeches, &c. in his cloak-bag, and called for his mule.

I am going forwards, said the stranger, for Franckfort—and shall be back at Strasburg this day month.

I hope, continued the stranger, stroking down the face of his mule with his left-hand as he was going to mount it, that you have been kind to this faithful slave of mine—it has carried me and my cloak-bag, continued he, tapping the mule’s back, above six hundred leagues.

—’Tis a long journey, Sir, replied the master of the inn—unless a man has great business.—Tut! tut! said the stranger, I have been at the promontory of Noses; and have got me one of the goodliest and jolliest, thank heaven, that ever fell to a single man’s lot.

Whilst the stranger was giving this odd account of himself, the master of the inn and his wife kept both their eyes fixed full upon the stranger’s nose—By saint Radagunda, said the inn-keeper’s wife to herself, there is more of it than in any dozen of the largest noses put together in all Strasburg! is it not, said she, whispering her husband in his ear, is it not a noble nose?

‘Tis an imposture, my dear, said the master of the inn—’tis a false nose.—

‘Tis a true nose, said his wife.—

‘Tis made of fir-tree, said he,—I smell the turpentine.—

There’s a pimple on it, said she.

‘Tis a dead nose, replied the inn-keeper.

‘Tis a live nose, and if I am alive myself, said the inn-keeper’s wife, I will touch it.

I have made a vow to saint Nicolas this day, said the stranger, that my nose shall not be touched till—Here the stranger, suspending his voice, looked up—Till when? said she hastily.

It never shall be touched, said he, clasping his hands and bringing them close to his breast, till that hour.—What hour? cried the inn-keeper’s wife.—Never!—never! said the stranger, never tell I am got—For heaven sake into what place? said she.—The stranger rode away without saying a word.

Appendix III

Letter CXIX To J – H – S Esq. (Dec. 1767)[5]

Literas vestras lepidissimas, mi consobrine, consobrinis meis omnibus carior, accepi die Veneris; sed posta non rediebat versus Aquilonem eo die, aliter scripsissem prout desiderabas. Nescio quid est materia cum me, sed sum fatigatus et aegrotus de meâ uxore plus quam unquam – et sum possessus cum diabolo qui pellet me in urbem – et tu es possessus cum eodem malo spiritu qui te tenet in deserto esse tentatum ancillis tuis, et perturbatum uxore tuâ – crede mihi, mi Antoni, quod isthaec non est via ad salutem sive hodiernam; sive eternam; num tu incipis cogitare de pecuniâ, quae, ut ait Sanctus Paulus, est radix omnium malorum, et non satis dicis in corde tuo, ego Antonius de Castello Infirmo, sum jam quadraginta et plus annos natus, et explevi octavum meum lustrum, et tempus est me curare, et meipsum Antonium tacere hominem felicem et liberum, et mihimet ipsi benefacere, ut exhortatur Solomon, qui dicit quod nihil est melius in hâc vitâ quàm quòd homo vivat festivè et quòd edat et bibat, et bono fruatur quia hoc est sua portio et dos in hoc mundo.

Nunc te scire vellemus, quòd non debeo esse reprehendi pro festinando eundo ad Londinum, quia Deus est testis, quòd non propero prae gloria, et pro me ostendere; nam diabolus iste qui me intravit, non est diabolus vanus, aut consobrinus suus Lucifer – sed est diabolus amabundus, qui non vult sinere me esse solum; nam cùm non cumbenbo cum uxore meâ, sum mentulatior quàm par est – et sum mortaliter in amore – et sum fatuus; ergo tu me, mi care Antoni, excusabis, quoniam tu fuisti in amore, et per mare et per terras ivisti et festinâsti sicut diabolus eodem te propellente diabolo. Habeo multa ad te scribere – sed scribo hanc epistolam in domo coffeatariâ et plenâ sociorum strepitosorum, qui non permittent me cogitare unam cogitationem.

Saluta amicum Panty meum, cujus literis respondebo – saluta amicos in domo Gisbrosensi, et oro, credas me vinculo consobrinitatis et amoris ad te, mi Antoni, devinctissimum.

L. STERNE

Letter to John-Hall Stevenson (author’s translation)

I received your most charming letter, my cousin, dearer than all my cousins, on Friday; but the post was not going back to the North on that day, otherwise I would have written just as you desired. I don’t know what is the matter with me, but I more sick and tired of my wife than ever – and I am possessed with a devil who drives me to the city – and you are possessed with that same evil spirit who holds you in the wilderness to be tempted by your maidservants, and vexed by your wife – believe me, my Antony, that this is not the road to salvation whether the present or eternal; for you begin to think about money, which, as St. Paul says, is the root of all evils, and you do not say enough in your heart, I am Antony from Crazy Castle, I am now more than forty years old, and I have completed my eighth lustrum, and it is time for me to look after myself, and to make that Antony of mine a happy and free man, and to do a kindness to my own self, as Solomon urges, who says that nothing is better in this life than that a man should live cheerfully and that he should eat and drink, and enjoy the good because that is his portion and dowry in this world.

Now we would wish you to know that I ought not to be censured for going in a hurry to London, because God is my witness, that I am not hastening on account of glory, and to make an exhibition of myself; for that devil who entered me, is not an idle devil or Lucifer his cousin – but he is a sexy devil, who does not allow me to be alone; for since I am not sleeping with my wife, I am hornier than usual – and I am in the way of mortals in love – and I am foolish; therefore you, my dear Antony, will pardon me, because you were in love, and you went across the sea and across the lands and you hurried like a devil to with the same devil driving you. I have much to write to you – but I am writing this letter in a coffee-house full of noisy company, who will not permit me to think a single thought.

Greetings to my friend Panty, I will reply to his letter – greetings to my friends in the house of Guisborough, and I beg that you believe I am in the bond of cousin-ship and love towards you, my Antony, most devoted.

L. STERNE

Notes

| ⇧1 | Letter from Sterne to Stephen Croft, 1760, quoted in M. Walsh, “Goodness nose: Sterne’s Slawkenbergius, the real presence, and the shapeable text,” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 17.1 (2008) 55–63. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | Analysis of Vol. 3, chs 11–20 can be found here. |

| ⇧3 | Sterne’s anti-Catholic sentiments were considerably softened later, after his travels to France and Italy: see, for example, the encounter with a monk at Calais in the opening chapters of his Sentimental Journey. |

| ⇧4 | For more on περιζώμα see Liddell and Scott and Wiktionary, I have two editions of Tristram Shandy in front of me – the Penguin Classics paperback originally from 1967 and an 1885 edition of the Complete Works of Laurence Sterne. In the Penguin version the word is given as περιζματε, while the older book prints it as περιζoματέ, which reflects the misspelling and misaccentuation found in the first edition of 1761. Was that intentional? |

| ⇧5 | The text and translation of this letter first appeared in my book Annus Mirabilis: More Latin for Everyday Life (The History Press, Cheltenham, 2009). |