Theresa Ryder

At 2 a.m. on the morning of my daughter’s birthday I kept my pledge to finish my Classics master’s dissertation by the time she turned seventeen. For a while she would get her wish for a more conventional mother. I saved the final version for printing and as I closed the laptop lid I realised that in my haste I had made a footnote error. I was too tired to care. Approaching my 50th year, I was done with academia. I turned to view my shelf of Classics books that I could now read for pleasure. They were mostly second-hand but all equally creased from much handling. I selected a small battered book with a dull reddish-brown cover and flicked its aging pages. My university education had come late in life but this book reminded me that the seed had been sown for Classics many years before.

A professional mitcher, I had left school aged fifteen with no qualifications. Fortunately my Irish parents had chosen London as their migration landing point and low-level jobs were plentiful there at that time. I built an eclectic CV of short-term roles that led me at the age of 21 to work as a sales receptionist in a driving school. My parents were impressed: an office job was a step up. My branch was at the foot of Harrow-on-the-Hill. Up that leafy slope was the famous Harrow School and down it trundled the sons of the wealthy, pitching up for driving lessons.

They were a fascinating bunch. Some had elastic bands around their shoes to keep their soles intact. Duct tape spliced many a torn trouser leg. Straw boater hats were removed on entry and clutched like steering wheels. To the one, they were all mute with shyness on approaching the desks in our all-female workplace. While they waited for their lessons, and many came curiously early, they sent us surreptitious glances from behind floppy fringes. They seemed to be always studying or talking to each other about schoolwork. Those fringes dipped into open books held in hands with nails frayed from nervous chewing.

These elite specimens captured my interest and I listened in as best I could to their conversations. They used a mysterious vocabulary speaking of each other as being Remove, Fifth and Sixth. Popular pastimes seemed to be “dodging the beaks”, “getting a skew”, or “asking for tolley”. Their speech was spattered with other curious words such as Cicero, iambic, participle, Flavians and, weirdly, frogs. They seemed to have an issue with an amphibian infestation on their school stage. Wasps also seemed to be a problem.

They asked each other if they had done their Homer. At first I thought they were saying homework but realised they couldn’t all be mumbling. They had an odd expression of endearment when asking each other, like an elderly aunt, if they had “finished, my dear”. Finished what? I yearned to ask. One announced to his peers, on entering the premises in a panic, that he has lost his Ovid. What, I wondered, was an Ovid. Perhaps some sort of tool? Another boy laughingly suggested it had morphed back into a tree. A wooden implement then? Possibly a paddle for some posh sport? Kept in a shed maybe? A clue when I thought I heard arachnids mentioned. I hoped he would find it soon, he seemed distraught and it sounded useful.

I befriended one of them. It took some time, as the boy seemed nervous around our lower society. There was something delicate about him that stopped us from teasing him as we did most of the others. Poor fellows, they had no choice but to sit in the office and take it. I knew from his driving lesson schedule that the delicate one’s name was Simon. He was a thoroughbred of blonde locks and evident lineage of good nutrition in his long limbs. Years before I discovered Charles Ryder and Sebastian Flyte on their road trip from Oxford, Simon showed me a photo of a wide stately home set on a hill of smooth green and said, “It’s where my mother lives.”

I was taking a tea break one morning when he came in. I knew he was expected so I had kept the kitchen door ajar. He stood in reception in his crumpled blazer, with tie askew and freshly washed hair judging by the bounce of his fringe. He clutched his straw boater with hands at 10 to 2, and on seeing me he raised one hand in a fleeting hello then parked it back in position. I waved an invitation to join me. A frown creased his noble brow– perhaps he had never seen a kitchenette before. All the more reason to encourage him further. Like a deer coaxed by food in an outstretched hand, he inched toward me. When he stepped in, I snared him by kicking shut the kitchen door. He sat hard on a plastic chair seeming panicked by the small cubicle. He was no doubt accustomed to more palatial space. I spotted a book stuffed into his blazer pocket and spoke first:

“What are you reading?”

“Just this.” He tugged out a small volume with a dull reddish-brown cover.

I took it and made out a naked muscular man with winged people behind him. “The Complete Plays of Sop…”

“Sophocles,” he pronounced before I messed it up too much. “What’s yours?”

I held up my chunky volume. “The Talisman.”

“Good?”

“Yea. It’s about a boy who flicks between two worlds.” I looked at Simon who was glancing around at our chipped mugs, instant coffee, and plastic cutlery. He looked lost. “Do you like your plays?”

“It’s just for an essay. Swap when you’re finished that? I have another copy.”

“Swap now if you like, I’ve read mine before.”

Our books switched hands and I scanned the dense language with a heavy heart.

“Start with Oedipus,” said Simon, no doubt seeing my dismay.

“Eedy Puss? What’s it about?”

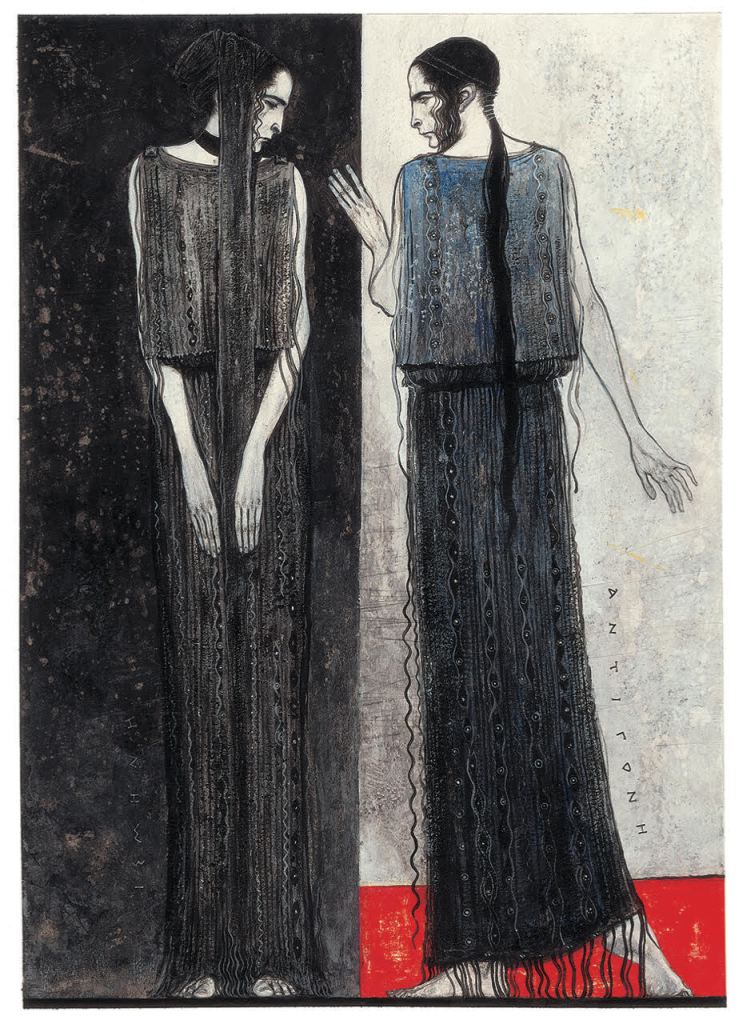

“He kills his father and marries his… maybe start with Antigone. She breaks the law to do right by her dead brother even though he’s seen as a criminal.”

“Sounds good. An-tig-oh-nee. I’ll remember that,” I opened the kitchen door. “Time’s up.”

“If you get stuck read it out loud,” he said, enthused by his release. “It makes more sense. A play is meant to be heard.”

“Will do.”

I couldn’t imagine an audience at home putting up with that. But I felt an obligation to at least tackle the book before I saw Simon again.

I tried. Alone on a Saturday afternoon I tucked into an armchair and began to follow the adventures of Antigone and the other oddly named characters. The struggle hit quickly. They were giving it to me in English but may as well have spoken in tongues. It reminded me of the attempt I had once made to read the hefty, leather-bound Bible that my parents had been given as a wedding present. I had no religious intent but a curiosity as to what was printed on the lightweight gold-rimmed pages. It turned out they too were heavy with language, littered with “begats” and “thou shalts”.

Unlike the Bible, I persevered with Antigone and got the gist of most of the story but, at a long speech from Creon, I gave up and flicked forward. I settled on a page with a list of one-liners. Feeling a little guilty at skipping on, I paused to take Simon’s advice and, standing in readiness to perform, I read aloud the short snappy sentences. I had never seen a play but I gave it my all, belting it out with loud emotion, one arm held high. The words came easily in rapid succession. I had landed in the middle of a heated row between two sisters and their uncle, each jumping in with equal outrage. A family spat. I could relate. I read on to the shocking end where the wasted energy of their efforts surged within me and settled in unfamiliar emotion. I was caught somewhere between my world of the living room and this strange yet oddly familiar new one. Semi-detached, I stared out the window until a neighbour’s methodical hedge clipping brought me back.

Next came Oedipus Rex and I was immediately there with those people mourning in the midst of a plague. I presumed the burning incense was a practicality to cover the smell of the dead and dying – I had no notion of appeals to the gods. I had started to get used to the style and it became a page turner from the outset. Here again was my now-beloved Antigone but as background to the action. Uncle Creon had a bigger role. The story, and lives, unravelled. The twist coming with a bloody fight at a crossroads. Oedipus, the hero and King who cannot see the truth, departs as a blinded beggar. It was perfect.

I was eager to report back to Simon but he didn’t come back for his book or return mine. I checked his records and found that he had passed his driving test. He would have no cause to return to the driving school. He had a career and lifestyle waiting to embrace him. I got busy living my more modest life. I didn’t give much thought to Sophocles but I did start to go to plays. They were local amateur dramatic productions in dusty halls where I sat on hard-backed chairs and chased the sensation of my first hit.

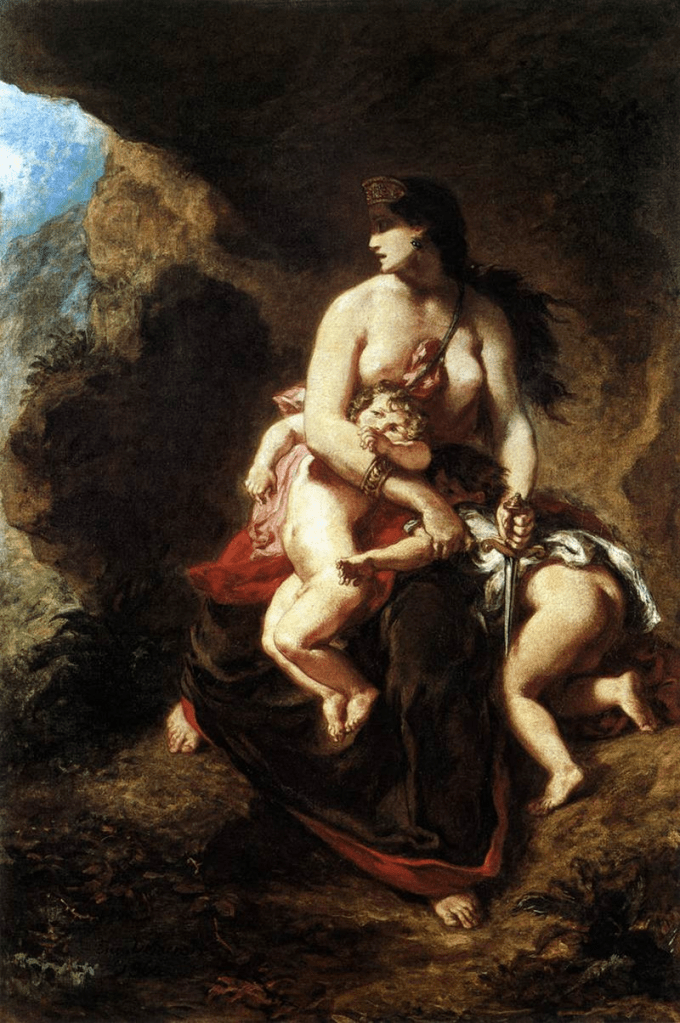

It was twenty years and three children later when I decided to make up for a lost education. I had by then retraced my parents’ footsteps to live in Kinnegad, near my mother’s birthplace in Ireland. I had no idea how to go about gaining qualifications or even what to study but I saw an advert for a one-year distance course with the Open University and took up the challenge. The study pack for An Introduction to the Humanities arrived in the post and there among the lesson plans for the eight disciplines on offer was a play. Described as a Greek tragedy, its title stirred a memory from the waiting driving lesson boys and explained their oddly affectionate “my dear”: I opened the lesson outline for Medea.

A different playwright now, Euripides. The accompanying CD taught me how to pronounce the tricky names, explained the role of the chorus and described the stage movement. In the cast list I was delighted to find Creon. I settled in to read, eager to see what he was up to this time. The opening scene was set by ordinary folk, a nurse and tutor, gossiping. Trouble came early. Here was the nurse warning the children not to go near their mother. This was not going to be tame. And Medea, declaring she would rather stand three times in battle than give birth once, was ferocious and frightening unlike the righteous Antigone. I ploughed on. Medea raged on every page. She even out-spoke Creon, a man the playwrights had gifted with lengthy oration. I read quickly, captured, spellbound, and horrified to its outrageous end. It was a rocking start to my career as a student.

When the Open University year was over, I looked around for further learning opportunities and discovered an Open Day at Maynooth University. On a freezing Saturday in November I roamed the stalls listening over shoulders. I loitered longest at the stand reserved for Classics. Too timid to engage that day, I went home and applied for a place as a mature undergraduate Arts student. In a short time I was interviewed, accepted, and signed up for my chosen disciplines in Anthropology, History, and Greek and Roman Civilisation. On my first day, silent with nerves and imposter syndrome, I sat at the back of an introductory lecture given by the Classics Department. It was an overview of the year ahead. The lecturer held up a chunky black paperback. The cover image was a woman carved from marble with tree limbs growing from her hands. Beneath her, the title Metamorphoses. I smiled and settled in, eager to begin. I had found my Ovid.

Theresa Ryder is a writer and teacher with an M.A. in Classics from Maynooth University. She is a winner of the Molly Keane Creative Writing award whose work has been widely published. Recent contributions include The 32: an Anthology of Irish Working Class Voices (Paul McVeigh ed., Unbound, London, 2021), The Same Page Anthology (University College Cork Press, 2021), The Honest Ulsterman, and The Irish Times. Earlier this year, her play Ritual Dance was selected for performance in the Cork Arts Theatre Views from a Window. She is currently developing a new play based on her commission to rework an ancient myth for the Actors of Dionysus, as well as writing a memoir of her years as assistant to the late author, J.P. Donleavy.