Alfred Deahl

A couple of months ago I wrote an article about Domitian II, a 3rd-century AD usurper of the Roman imperial throne whose existence was only confirmed by two chance coin discoveries. The 3rd century was a wild era which saw numerous usurper ‘emperors’ claim political power throughout the Roman Empire. Generals used their armies to wrest political control, resulting in widespread instability across the empire from the death of Severus Alexander (AD 235) until the stability Diocletian achieved with the tetrarchy (from 284 onwards).

Domitian II was one of these figures in what we call the ‘Gallic Empire’ (c.260–74), a secessionist region which the Batavian commander Marcus Cassianus Latinius Postumus (dates unknown) snatched from Gallienus (ruled 253–68). Domitian was most probably involved in the deposition of Victorinus (who ruled in the late 260s or early 270s), but failed to hold power against Tetricus’ rival claim (Tetricus ruled the Gallic Empire in 271–4).

The Gallic Domitian’s existence in the historical record was established by two coin finds. The first, discovered in 1900 and in France, was assumed to be fake until another identical coin showed up in an Oxfordshire coin hoard in 2003. Through these chance finds a new emperor was added to history.

Quite fortuitously, shortly after I published my article on Domitian II, the same sort of discovery seems to have happened again. On, 23 November, Paul N. Pearson et al.[1] published a paper authenticating a gold coin of the emperor ‘Sponsian’. This has been widely reported in the news since – something which certainly doesn’t happen every day with Roman coins.

The coin was found among others in 1713 in Transylvania, according to a handwritten note by Carl Gustav Heraeus (1671–1725), Inspector of Medals for the Imperial collection in Vienna, Austria. Heraeus’ note details the acquisition of eight coins from the Hapsburg finance minister. The coins are thought to have been part of a larger group which was broken up when this smaller group was put on the market.

Two of these coins, one silver and one gold, featured the name Sponsian – a hitherto-unknown Roman general. Heraeus believed that they were imitation coins that were struck in antiquity. Counterfeit coins of this sort, called ‘barbarous radiates’, were frequently struck in this period. The political disruptions of the 3rd century had a major impact on Roman money in general; one result of that disruption was acute shortages of small change in areas of northern Europe in particular. These regions turned to striking imitation coins purely to meet demand. But despite Heraeus’ assessment, scholarly consensus soon condemned the coins as modern forgeries. The great numismatist Henry Cohen (1806–80) wrote, “Je regarde ces pièces comme des coins modernes ridiculement imaginés et très-mal faits” (“I regard these items as modern coins, laughably conceived, and very poorly executed”).

Pearson’s team, however, sought to exonerate Heraeus’ discovery of the ‘Sponsian’ coin, which is now in the Hunterian collection in Glasgow. His paper features a study of the deep micro-abrasion patterns on this coin, through non-destructive imaging and spectroscopic results. The team found the relevant features of the coin to be consistent with genuine test samples indicating extensive circulation wear and deposits of minerals from a long period of burial underground. Despite the sophistication of forgeries in Heraeus’ day, Pearson has concluded the gold coin to be genuine (the silver one has been lost for generations) and thus an affirmation of the historical existence of Sponsian.

Pearson, in both the paper and his book on the Third Century Crisis (published earlier this year), discusses where we can fit Sponsian within the broader historical picture. The Sponsian coin was found with coins of Gordian III (AD 238–44) and Philip I (244–9), making it possible that he attempted to usurp around the downfall of Philip I in 249. A later date is also suggested in the 260s, during the solo reign of Gallienus (260–8). Pearson also assumes that the find location of the coin indicates where Sponsian attempted to usurp the imperial throne, placing him as a military commander in the province of Dacia – Pearson helpfully provides a plausible map in his book:

Both book and paper combine to establish Sponsian as an authentic usurper emperor during this turbulent period, one who would have been lost to history without this coin’s discovery. Sponsian is thus another “Domitian II” figure.

But this is all too good to be true. Too many assumptions have been left unquestioned in this ‘authentication’, and there are major problems with the interpretation of the data in the paper. What seems particularly odd is that the paper points out many of these very problems, yet manages to conclude the exact opposite of what the reader expects.

First of all, it is well noted that this coin looks really odd. You do not have to know much about Roman coins to tell it looks strange, and this indeed has been the main criterion for dismissing it in the past. The portrait has strange features atypical of coins in this period and more typical of the ‘barbarous radiate’ imitations. Yet these imitations are always low-value pieces in copper, and crucially were never struck in gold. The coin’s legend is also problematic, reading IMP[erator] SPONSIANI, putting the usurper’s name in the genitive case (i.e. “of Sponsian”), which was not a standard Roman monetary convention. There are no additional titles or names, and the legend only goes partially around the portrait. All these elements combine to render the coin’s legend, not merely unusual, but in fact wholly unique and unprecedented.

Things get worse on the reverse. The reverse type is a genuine one that has been found before – but only on one single issue of Republican-era denarii, made almost four hundred years prior to the purported date of this coin.

There are no equivalent examples of Imperial coins that look so far back to a small, insignificant coin type from so many centuries earlier. The forger has clearly made a mistake. The ‘reverse legend’, which features on both the Sponsian coin and the Republican denarius, reads C AUG, short for Caius Augurinus. The forger has assumed the AUG was short for Augustus, a title used on nearly all imperial coins. This is a very bad mistake which itself rules out any possibility that the coin might have been genuine.

Pearson’s explanation for this is perhaps the most fatally unsubstantiated claim of the paper. He suggests that this was a conscious borrowing of a much earlier Republican type to create confidence in the usurper’s currency in the context of widespread debasement. This seems uniquely odd, especially as the Republican type in question in not a common one – who could have even known about it – in Dacia of all places?

But there is more evidence which condemns the coin further. This is provided by its very fabric. The small circular holes which pepper the obverse are familiar to all coin collectors who have examined forgeries. These are the traces of relict bubbles caused in the casting process. Unlike all authentic Roman coins, this coin is cast in a mould, not struck between two dies. Bizarrely, such a production method makes Pearson interpret this as a unique innovation, rejecting the far more obvious conclusion that it is a modern forgery.

Modern forgeries began in the 16th century and became very accomplished. Famously the ‘Paduan Medallions’ of Giovanni Cavino (1500–70), which were not intended to deceive, look very genuine:

Forgeries became highly detailed, often using particular types from genuine coins to make the moulds. Forgers frequently distressed the coins – famously, Carl Wilhelm Becker (1771–1830) in the 18th century put coins in bags of iron filings which he attached to the axle of his carriage; this process gave them a worn patina.

Another problem with the coin is its weight and fineness. The weight is too heavy for gold of the time, and the scanning electron microscopy indicates that it is atypical compared to the test pieces, and even to the other coins from this assemblage:

The Sponsian coin is a clear outlier with a much higher copper impurity than its counterparts. Pearson takes this as evidence that Sponsian was using a different gold supply for his unique issue of cast gold coins. Dacia had good natural supplies of these minerals. But what this really seems to suggest is production using a modern, 18th-century, source of gold, with a very different composition to the gold supplies of the 3rd century.

The final nails in the coffin are the other coins from the assemblage which are thought to have been found with it. Those too are suspicious, not least in their types. One allegedly is a Republican type of Plautius Plancus (RRC 453/1), and another one (now lost) was allegedly a gold stater of Alexander the Great (356–323). This variety dispels any notion that the assemblage could have been a genuine hoard, with coins made of such disparate materials, and over such broad periods of time: it is very unusual to find hoarded gold with bronze, for instance.

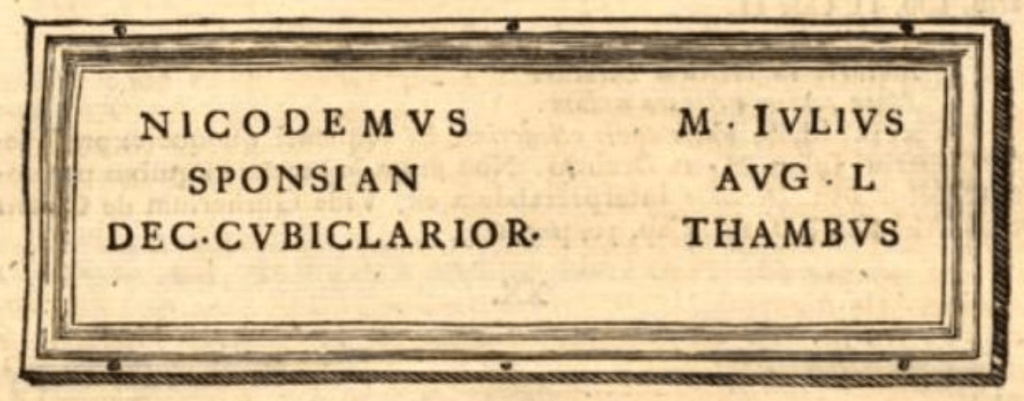

My conclusion from all of this is that the ‘Sponsian’ coin is very clearly fake; moreover, Cohen was right – this coin is a bad fake. An amusing detail is that there is only one ‘Sponsian’ attested in antiquity: on a funerary inscription for the cubicularius (chamberlain) of the empress Livia (59 BC–AD 29). It is a remarkably rare name, one which a forger simply would not have known, especially as the inscription was found in the 1720s, after the alleged 1713 find date.[2] This has been interpreted as evidence for the coin’s authenticity – how could a forger using a significant amount of gold have made such a bad forgery in every regard, even to the point of making up a random, almost-unattested, Roman-like name? This argument, essentially that the coin seems such a bad fake that it must be genuine, appears to be Pearson’s chief argument for its authenticity. I suggest that this is not a strong position.

I propose instead that we have here a bad fake, by a forger so unskilled that not only does he fail to produce something that looks like a Roman gold coin; he has even made up a random Roman-sounding name. Every aspect of this coin, from the name, to the gold, to the reverse image, is suggestive of inauthenticity, if not downright ludicrous. A final point here is that the patterns of micro-abrasions on the coin can hardly be taken as evidence that the coin was ever in circulation. Numismatists, in general, refrain from taking surface wear as indicative of circulation, as this never occurs at a fixed rate in any regular way. My expectation would be that similar analysis of the worn Paduan medallion would, in any case, show similar patterns.

Forgers had, and still have, numerous clever ways to distress a fake coin, and the methodology thus far used to study the Sponsian coin is inadequate to root them out, especially when so much of the evidence supports the opposite conclusion.

It seems to me clear that on this occasion we do not have another Domitian II-type discovery: any idea of an ‘Emperor Sponsian’ should remain in the realms of fiction. Where Pearson remarks “Indeed it is surprising no well-attested find of this type has been found in modern times,” I am not surprised. This is the case with many a fake…

Alfred Deahl is an undergraduate reading Classics at Queens’ College, Cambridge. He has previously written for Antigone on the evolution of Roman coinage, the chaotic character of Alcibiades, and the discovery of Domitian II. He is a keen metal detectorist but is yet to find a hoard.

Further Reading

Paul N. Pearson, Michela Botticelli, Jesper Ericsson, Jacek Olender & Liene Spruženiece, “Authenticating coins of the ‘Roman emperor’ Sponsian”, PLOS One 17(11) (Nov. 2022): e0274285. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274285. This paper can be freely read here.

Paul N. Pearson, The Roman Empire in Crisis, 248–260: When the Gods Abandon Rome (Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, 2022).

Clifford Ando’s Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century (Edinburgh UP, 2012) provides a great overview of the period and I would also recommend Alaric Watson’s Aurelian and the Third Century. For a numismatic overview, The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage (Oxford UP, 2011; available here for those with access) provides a comprehensive coverage. Chapters 28 and 29 are especially relevant for this piece.

Notes

| ⇧1 | Namely, Michela Botticelli, Jesper Ericsson, Jacek Olender, Liene Spruženiece. The full citation is given under ‘Further Reading’. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | This figure recurs, abbreviated to Spons, in another funerary epigram: CIL VI 5263 = CLE 988, but this was not published until 1855, and would not allow the inference of the full name. |