Livio Zerbini

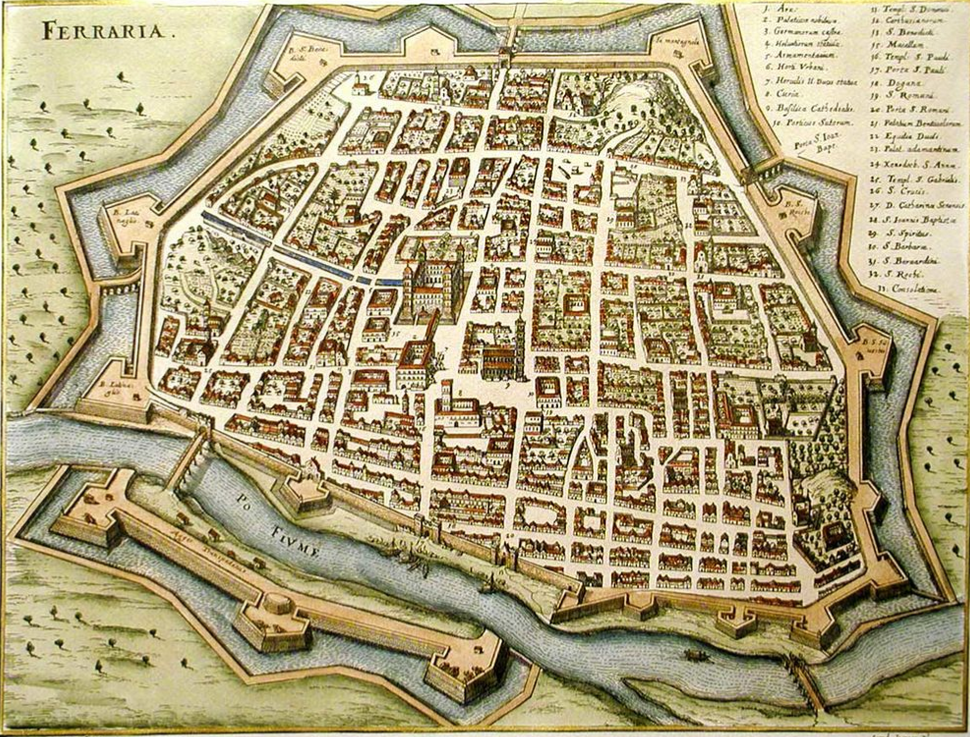

In late March this year, classicists, historians, and archaeologists from different countries met at the University of Ferrara in Italy to discuss new and creative ways to teach and promote ancient history in schools and universities, and to the public. The organizer of the conference was Professor Livio Zerbini, who teaches Roman history and Latin epigraphy at the University of Ferrara and directs Italian archaeological missions in Apsaros (Georgia) and Tibiscum (Romania).

Here Professor Zerbini answers a range of questions posed by Dobrinka Chiekova for Antigone.

In March 2023 you co-founded ENSTARH (European Network for the Study and Teaching of Ancient Roman History), and in March the following year the First International Conference of ENSTARH took place at the University of Ferrara. Could you tell us a little more about the goals and the mission of ENSTARH?

The idea behind ENSTARH was to create a network between universities, schools, research centres and other such institutions across Europe, with the aim of promoting the importance of ancient studies, with a particular focus on Rome and its empire, whose legacy is still alive and active. The Roman legacy represents a great common heritage that risks being increasingly ‘ghettoized’ in school and university courses in the name of modernity. This is a short-sighted cultural policy, because in this way we risk forever losing a fundamental element of our identity. ENSTARH aims to form a strong network and commit all our members to inspire people – especially in the younger generations – to understand that in order to have a future, we cannot ignore our past.

How did you become interested in studying the ancient world, in particular Roman history? Could you point to any persons, books or experiences that inspired you to choose your professional path?

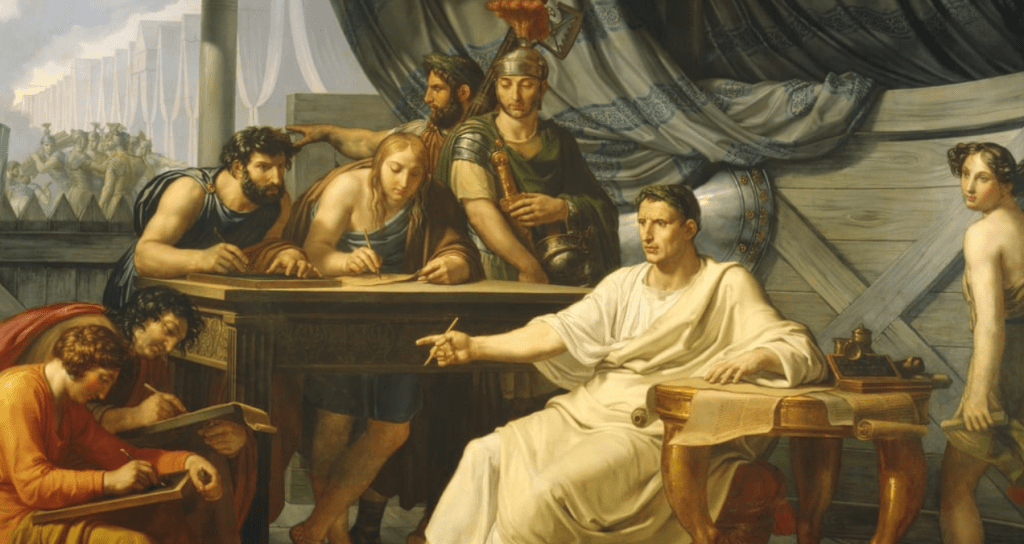

I began to be passionate about ancient Rome and its history when I was a child; indeed, I remember an episode that perhaps determined my future choices. I was six years old; my parents gave me a book, whose title was The Great Book of History. I still have it, since it was the first book in my personal library. Having opened the book on a random page, I came across the figure of Julius Caesar, and read about his life with great interest. I believe that my passion for the history of Rome comes from there. But obviously I was then able to fuel this passion by meeting great masters, who all had a common trait: a profound humanity. I mention some of them: Maria Bollini, Giancarlo Susini, Gabriella Poma, Angela Donati, Attilio Mastino, Géza Alföldy, Radu Ardevan and Ioan Piso. Some of these later became great friends; unfortunately, others have disappeared. In some way we become the people we have known in our life.

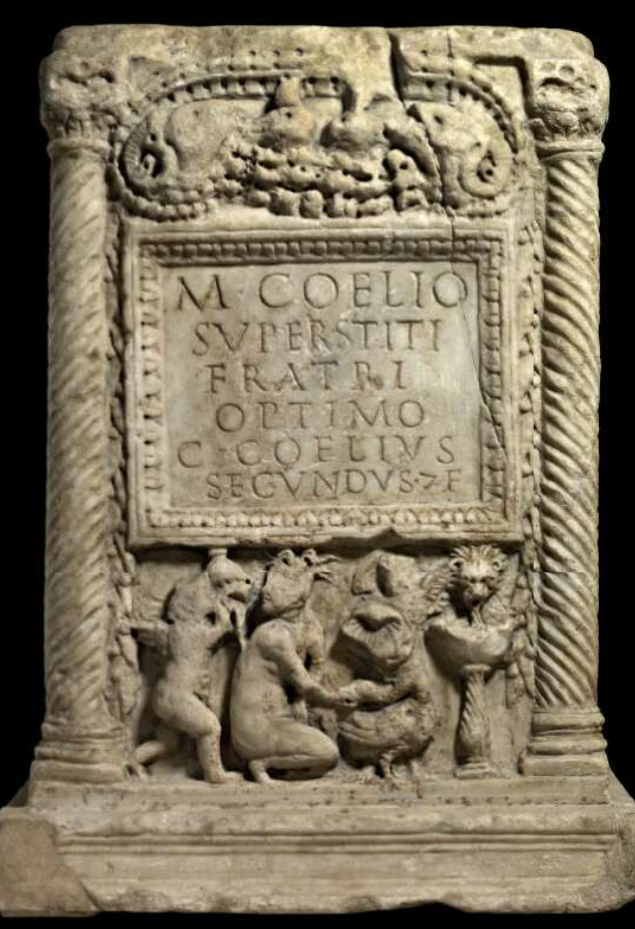

How did you become interested in Latin epigraphy, and how does epigraphy differ as a discipline from the literary and philological study of written texts?

I began to be interested in Latin epigraphy from my early years at university, once I grasped what its intimate essence is, namely to be a form of public communication, which informs us about countless aspects of political, economic and social life of the Roman world. While historiographical sources generally tell us about the characters who made history or were, in various ways, in the orbit of power, epigraphy allows us to bring to light the experience of those people who remained on the margins of history, yet who still provide us with a vivid representation of what Roman society was. Because of this, epigraphy enriches and completes literary and philological sources. In personal terms, my epigraphical studies on the essentiality of the message that inscriptions convey allowed me to sharpen my attention to words and their use, which led me to read and interpret literary and philological sources with greater rigour and precision.

As one of the foremost specialists on the Danubian limes (‘frontier’) and the Danubian provinces of the Roman Empire, you are also the founder and Director of the Laboratorio di studi e ricerche sulle Antiche province Danubiane (‘Laboratory for the Study of the Ancient Danubian Provinces’) at the University of Ferrara, which since 2009 has organised biennial international conferences, assembling hundreds of experts on the history, epigraphy, and archaeology of this region. Could you tell us more about this initiative?

I have always believed in the importance of a more active international collaboration between colleagues, with the aim of sharing scientific interests and projects. For this reason, in 2007, I created the Centre on the Danube Provinces (LAD) here at Ferrara. I approached the history of the provincial world because I realized that Rome is better understood outside of Rome – and even very far from Rome – due to the extraordinary power of penetration that Roman civilization had well outside the limes. The Centre on the Danube Provinces organizes international conferences every two years, in partnership with other universities, which have now become points of reference for the study of the Danubian horizon in Antiquity. The next one will be held in Sofia and Vidin, Bulgaria, from 23 to 29 September this year.

You have published articles and books on multiple aspects of Ancient Roman society, on the cultural synthesis and integration of different ethnic groups and traditions, and on the processes of Romanisation. Based on your extensive scholarship, what do you think is important and relevant for us today, as citizens of different countries and participants in an interconnected world, to learn from the history and culture of Ancient Rome?

Despite years of studies and research, I am still fascinated by Rome’s extraordinary ability to face the challenges of those times. In this regard, just think about how Rome made the principle of inclusion one of its greatest strengths. It wasn’t important to be Italic, Gallic, African or Syrian: the important thing was to feel to belong to a communis patria. Roman citizenship in this sense was an extraordinary instrument of inclusion. In one of my recent books, published a few months ago, The Strength of Ancient Rome: A Model for Italy Today, I highlight how Rome should be taken as a model for overcoming the increasingly complex challenges of modernity. Rome, from a small village of shepherds and farmers, became a great empire because four cardinal points oriented it from the beginning: inclusion, meritocracy, technological development and communications.

You have dedicated biographical books to several Roman emperors – Trajan, Caligula, and Commodus. Which one has been the most absorbing to study and write about?

The emperor who fascinated me the most was Caligula. To write a biography on Caligula means dealing with ancient historiography of senatorial origin which represented the princeps as a dissolute madman. What I tried to do with Caligula, to explore his Principate further, was to try to understand the motivations and reasons for his political actions, which were significantly influenced by his personality and his behaviour, not to mention his advisers, who differed considerably from those hired by Augustus and Tiberius. His unconventional and dissolute life was undoubtedly influenced by the terrible experiences Caligula went through in his adolescence, from the elimination of his mother Agrippina and his two older brothers to the climate of suspicion and danger in which he found himself during the years he lived at the court of Tiberius. Caligula had a short reign as emperor of Rome, just under four years, but nevertheless went down in History as a mad and cruel tyrant.

However, what emerges from ancient authors is that Caligula, although not clinically insane, was so caught up in the sense of his own pre-eminence that he practically felt no sense of moral responsibility or restraint. Caligula – beyond what ancient authors (and especially Suetonius) tell us – was not crazy, nor (as can be seen above all in Suetonius’ own narrative!) completely incapable of governing or undertaking political initiatives. In Roman historiography, Caligula’s private life (and the consequent gossip) seems to have been inflated beyond all proportion, compared to his political work and acts of governance, which are reduced to the point of being almost non-existent. Yet the four years of Caligula’s rule were not so insignificant. His reign clearly demonstrated how the institutional structure created by Augustus risked degenerating into an absolutist power in the face of a princeps with despotic tendencies.

You are also an archaeologist, and as the Director of two Italian archaeological missions you conduct excavations in Apsaros, Ancient Colchis (Georgia) and Tibiscum (Romania). Could you share with our readers why the Black Sea is such an important region for the field of Ancient Mediterranean studies? What are the most important and most exciting archaeological discoveries of your career so far?

The Black Sea demonstrates that the geopolitical areas that were crucial in Antiquity remain so today, if we think about what happened in Crimea and what unfortunately is happening with the war in Ukraine. In Apsaros, on the Black Sea coast, I am excavating a Roman military camp located well outside the limes. In fact, on the eastern coast of the Black Sea the Romans had built a series of castra, of which that of Apsaros was the largest, which were to serve in a certain sense as a deterrent towards the kings of neighbouring kingdoms, such as the King of Iberia, and of those Caucasian populations who were more bellicose.

These petty kingdoms were exploited by both Romans and Persians as proxies during their eternal war, or else acted as buffer states between them, in the same way that small states have been used by America or Russia. But the most important discovery I made – together with Professor Wakhtang Licheli of the University of Tbilisi, Georgia – was the identification near Tmogvi-Tsundadi of an imposing necropolis dating back to the Bronze Age, of extraordinary scientific interest.

You have collaborated with many popular historical and archaeological magazines, and radio and television programs (such as RAI 3 and RAI Storia), aiming to share with the broadest possible audience the fascination with the history of the ancient world – a goal you share with Antigone. Why do you think that it is important to make scholarship in Classics, Ancient History, and Archaeology accessible to everyone?

I have always considered the circulation of my work on antiquity to be of the utmost importance. Sometimes we scholars are so completely absorbed in our studies that we forget to share them outside the world of ‘experts’. The ancient world exerts a great fascination among many people; sometimes those who disseminate this material in popular media and social media lack adequate preparation, and thus end up fuelling stereotypes and clichés, which end up giving the public a distorted image of history. This is precisely the reason I have always believed that spreading true knowledge of Antiquity is a scholar’s essential duty. I have tried to fulfil this in my own small way. In this regard, I think Antigone and ENSTARH show great foresight in sharing this great heritage that has been gifted to us by the ancient world.

Livio Zerbini is an historian, archaeologist and public intellectual at the University of Ferrara. He has taught as a visiting professor at several European universities, including the Sorbonne in Paris, and was awarded two honorary degrees. He founded and directs the LAD (Laboratory for the Study of the Ancient Danubian Provinces) and ENSTARH (European Network for the Study and Teaching of Ancient Roman History) and also directs the Black Sea International Centre, based in Batumi, on the Black Sea. In addition, he has directed the Italian Archaeological Mission in Tibiscum and the Italian Archaeological Mission in Apsaros (Georgia) for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A member of the committee of the AIEGL (Association Internationale d’Épigraphie Grecque et Latine), he has published very widely, especially in the fields of Roman history and Latin epigraphy.